Contractual Doctrine and the •Œselfâ•Š Versus •Œstateâ•Š Imposed Obli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

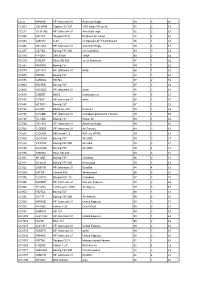

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

ALPA Los Angeles Field Office Records

Air Line Pilots Association Los Angeles Field Office 1955-1989 (Predominately 70s & 80s) 18 Storage Boxes 1 Manuscript Box Accession #247 Provenance The papers of the Airline Pilots Association of the Los Angeles Field Office were deposited to the Walter P. Reuther Library in 1976 and have been added to over the years since that time. Last addition was in 1991. Collection Information This is composed mainly of correspondence, minutes, reports and statistic concerning various airlines. The largest represented airlines include Continental Airlines, Flying Tiger Line, Trans World Airlines and Western Airlines. Important Subjects Air Safety Forum Airworthiness Review Briefs of Accidents Continental Airlines (CAL) Delta Airlines (DAL) Engineering & Air Safety Flying Tiger Line (FTL) LAX Area Safety Master Executive Council (MEC) Pan American World Airways (PAA) Trans World Airlines (TWA) United Airlines (UAL) Western Airlines (WAL) Important Correspondence Continental Airlines (CAL) Flying Tiger Line (FTL) Master Executive Council (MEC) Pan American World Airways (PAA) Trans World Airlines (TWA) United Airlines (UAL) Western Airlines (WAL) Box 1 1-1. AAH; Agreement; 1977 1-2. AAH; Amendment to Agreement; 1975 1-3. AAH; B 737 Crew Complement; 1971 1-4. Accident Investigation Committee; 1979 1-5. Active Grievances; 1966-1967 1-6. Age; Wage Analysis; 1974-1979 1-7. Air Safety Forum; 1955 1-8. Air Safety Forum; 1956 1-9. Air Safety Forum; 1957 1-10. Air Safety Forum; 1964 1-11. Air Safety Forum; 1968 1-12. Air Safety Forum; 1969 1-13. Air Safety Forum; 1972 1-14. Air Safety; General; 1967-1973 1-15. Air Safety Newsletter; 1958-1959 1-16. -

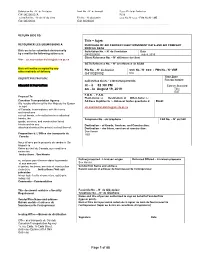

G410020002/A N/A Client Ref

Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amd. No. - N° de la modif. Buyer ID - Id de l'acheteur G410020002/A N/A Client Ref. No. - N° de réf. du client File No. - N° du dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME G410020002 G410020002 RETURN BIDS TO: Title – Sujet: RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: PURCHASE OF AIR CARRIER FLIGHT MOVEMENT DATA AND AIR COMPANY PROFILE DATA Bids are to be submitted electronically Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date by e-mail to the following addresses: G410020002 July 8, 2019 Client Reference No. – N° référence du client Attn : [email protected] GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG Bids will not be accepted by any File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME other methods of delivery. G410020002 N/A Time Zone REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Sollicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Fuseau horaire DEMANDE DE PROPOSITION at – à 02 :00 PM Eastern Standard on – le August 19, 2019 Time EST F.O.B. - F.A.B. Proposal To: Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Canadian Transportation Agency Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions à: Email: We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in right [email protected] of Canada, in accordance with the terms and conditions set out herein, referred to herein or attached hereto, the Telephone No. –de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. -

November 2015

Police Aviation News November 2015 ©Police Aviation Research Number 235 November 2015 PAR ©Airbus Helicopters Charles Abarr Police Aviation News November 2015 2 PAN—Police Aviation News is published monthly by POLICE AVIATION RESEARCH, 7 Wind- mill Close, Honey Lane, Waltham Abbey, Essex EN9 3BQ UK. Contacts: Main: +44 1992 714162 Cell: +44 7778 296650 Skype: BrynElliott E-mail: [email protected] Police Aviation Research Airborne Law Enforcement Member since 1994—Corporate Member since 2014 SPONSORS Airborne Technologies www.airbornetechnologies.at AeroComputers www.aerocomputers.com Avalex www.avalex.com Broadcast Microwave www.bms-inc.com Enterprise Control Systems www.enterprisecontrol.co.uk FLIR Systems www.flir.com L3 Wescam www.wescam.com Powervamp www.powervamp.com Trakka Searchlights www.trakkacorp.com Airborne Law Enforcement Association www.alea.org LAW ENFORCEMENT AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA: Aerial camera footage taken from a police helicopter at a fatal siege in September was dismissed as “defective” by an Australian Coroner, Mark Johns. An inquest into a police shooting near Tailem Bend looked into the death by shooting of Al- exander Kuskoff at his farm on September 17. Kuskoff, 50, had fired guns at police during the five-hour standoff, which ended in him being fatally shot by an officer from a range of 139m. During the standoff, Mr Kuskoff allegedly fired a number of shots at officers and the police helicopter, which had been hovering above the property. The helicopter was forced to move away from the scene and settings on an in-flight recording system were altered, leading to footage of the incident being compromised. -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

Aviation Where Career Opportunities Are Bright, Counselor's Guide

DOCUMBIIT NRSUM6 ED 026 481 VT 006 210 By Zaharevi tz, Walter; Marshall, Jane N. Aviation Where Career Opportunities are Bright, Counselor's Guide. National Aerospace Education Council, Washington, D.C. Pvb Date 68 Note-121p. Available from-National Aerospace Education Council, 616 Shoreham Buddin9.806 Fifteenth Street, NA. Washington, D.C. 20005 (document $3.00, record and filmstrip $10.00). EDRS Price MF-$0.50 HC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors-*Aerospace Industry, Career Opportunities, Employment Oualifications,Filmstrips, Occupational Guidance, *Occupational Information, *Occupations, *Resovrce Guides,Technical Education, Wages, Work Environment Identifiers -*Aviation Industry This aviation occupations guide is designed for use as a unit aswell as in conjunction with an aviation careers package ofmaterial that contains a WI strip and recording. Chapter One contains the script of the film strip,AviationWhere Career Opportunities are Bright, and includes all photographs used inthe film strip plus numerous amplifying statements. Chapters Two throughNine joresent information on occupational clusterswithin aviation: Aircraft Manufacturing Occupations,Career Pilots and Flight Engineers, Aviation Mechanics (Including Repairmen),Airline Careers, Airline Stewardesses or Stewards, Aviation Careers inGovernment, Airport Careers, and Aviation Education and Other Aviation Related Careers.Each chapter includes general information about an occupational cluster,specific jobs within that cluster, description of the nature of work, working conditions, wagesand benefits, and identifies where the iobs are as well as the schools or sources of training.(CH) VTC0218 AVI 0 WHERE CAREER OPPORTUNITIES ARE BRIGHT COMMELOR'S GUIDE 1115111101491r MISIN apsawmiew IDISMASIE TAM 31) Ng SEW? MEW OFFML OM II MILOK, BY Wafter Zahareirtiz' and 3qm-timelemovace4 Education Council ifb:st Edition 1968 AflON COVSC D.C. -

363 Part 238—Contracts With

Immigration and Naturalization Service, Justice § 238.3 (2) The country where the alien was mented on Form I±420. The contracts born; with transportation lines referred to in (3) The country where the alien has a section 238(c) of the Act shall be made residence; or by the Commissioner on behalf of the (4) Any country willing to accept the government and shall be documented alien. on Form I±426. The contracts with (c) Contiguous territory and adjacent transportation lines desiring their pas- islands. Any alien ordered excluded who sengers to be preinspected at places boarded an aircraft or vessel in foreign outside the United States shall be contiguous territory or in any adjacent made by the Commissioner on behalf of island shall be deported to such foreign the government and shall be docu- contiguous territory or adjacent island mented on Form I±425; except that con- if the alien is a native, citizen, subject, tracts for irregularly operated charter or national of such foreign contiguous flights may be entered into by the Ex- territory or adjacent island, or if the ecutive Associate Commissioner for alien has a residence in such foreign Operations or an Immigration Officer contiguous territory or adjacent is- designated by the Executive Associate land. Otherwise, the alien shall be de- Commissioner for Operations and hav- ported, in the first instance, to the ing jurisdiction over the location country in which is located the port at where the inspection will take place. which the alien embarked for such for- [57 FR 59907, Dec. 17, 1992] eign contiguous territory or adjacent island. -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

24 Annual National EMS Memorial Service

24thAnnual National EMS Memorial Service May 21, 2016 Hyatt Regency - Crystal City Arlington, Virginia About the Service The purpose of the National EMS Memorial Service is to honor and remember those Emergency Medical Services personnel who have given their lives in the line of duty and to recognize the ultimate sacrifice they have made for their fellow human beings. During the service a family member or agency representative will be presented with a United States flag which has flown over the U.S. Capitol, denoting the honoree’s service to their country, a white rose representing their undying love and a medallion signifying their eternal memory. Each person being recognized tonight is also represented by his or her state flag. After the reading of the names, there will be a National Moment of Silence. The names of those who are honored here appear on the "Tree of Life," the National EMS Memorial. 1 Program Announcer: Eric Johnson Director, National EMS Memorial Service Executive Director, Supporting Heroes Invocation: Reverend Stephen D. Carlson Director, National EMS Memorial Service Chaplain, Minnesota EMS Honor Guard Presentation of Colors: 2016 National EMS Memorial Service Honor Guard Pledge of Allegiance: Captain George Murphy, (Ret) Director, National EMS Memorial Service City of Boston EMS National Anthem: Paramedic Todd Metz American Medical Response Colorado Springs, Colorado 2 Program President’s Welcome: Jana C. Williams President, National EMS Memorial Service VP, Strategic Operations & Partner Development Med-Trans Corporation Song: "Much Too High a Price" Donald Coles Goochland County, Virginia Keynote Address: Chief James P. Booth Fire Department City of New York EMS Division Brooklyn, New York Presentations to Families Reader of Names: Brian Shaw Vice President, National EMS Memorial Bike Ride Deputy Director, Emergency Medical Services Institute Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 3 Program Presenters: Karen E. -

Case 3:21-Cv-00422-MAB Document 1 Filed 04/27/21 Page 1 of 42 Page ID #1

Case 3:21-cv-00422-MAB Document 1 Filed 04/27/21 Page 1 of 42 Page ID #1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS 1) TERESA BELYEU, ) 2) GARY BUDNICK, ) 3) KEITH COTTON, ) 4) BRIDGETTE DIAZ, ) 5) AMANDA DYKE, ) 6) JEFFREY FLYNN, ) 7) TIMOTHY GARRETT, ) 8) TINA GERLICH, ) 9) RYAN GLEASON, ) 10) PATRICK JOHNSON, ) 11) JERRY PENDLEY, ) 12) VINCENT POLSON, ) 13) MARINA STARK, ) 14) JORDAN TAKERIA, ) 15) GLEN THOMPSON, and ) 16) JONATHAN WATERS, ) ) Each individually and as class representaTives, ) ) Plaintiffs ) ) v. ) Case No. 3:21-cv-422 ) AIR EVAC EMS, INC. d/b/a AIR ) EVAC LIFETEAM, ) ) Defendant ) CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT The above noted Plaintiffs bring This action individually and on behalf of all others similarly siTuaTed (“The Class”) and allege as and for Their Class AcTion Complaint againsT Defendant Air Evac EMS, Inc. d/b/a AIR EVAC LIFETEAM (“Air Evac”), upon personal knowledge as To Themselves, and as To all other maTTers upon informaTion and belief, based upon invesTigaTion made by Their aTTorneys. Case 3:21-cv-00422-MAB Document 1 Filed 04/27/21 Page 2 of 42 Page ID #2 JURISDICTION AND VENUE 1. This Court has original jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C § 1331 and § 1332(d)(2). The matter arises under the laws of the United States, in particular 49 U.S.C. § 41713(b)(1). Further, the matter in controversy, exclusive of interest and costs, exceeds the sum or value of $5,000,000.00 and is a class action in which Plaintiffs and members of the Class are citizens of states different from Defendant. -

2018 Oklahoma Ambulance Registry

Oklahoma State Department of Health Protective Health Services Emergency Systems Emergency Medical Services Division 1000 NE 10th Street Oklahoma City, OK 73117-1299 Telephone: (405) 271-4027 Fax: (405) 271-4240 2018 Oklahoma EMS Division Certified and Licensed Agency Registry Table of Contents 2 Emergency Systems Personnel 3 Forward 4 List of Terms and Definitions 7 EMS Agencies Sorted by License Number 15 EMS Agencies Sorted by Agency Name 23 EMS Agencies Sorted by City 31 EMS Agencies Sorted by County 39 EMS Agencies Sorted by Region 49 Directory of Ambulance Providers 152 Certified Emergency Medical Response Agencies 181 EMS “522” Districts 183 2018 Statistical Analysis 1 State of Oklahoma____________________________ The Honorable Kevin Stitt Governor Oklahoma State Department of Health___________ Gary Cox Interim Commissioner of Health Protective Health Services______________________ Rocky D McElvany Deputy Commissioner James Joslin Assistant Deputy Commissioner Julie Myers, Dr.PH, CPHQ Chief, Medical Facilities LaTrina Frazier, Ph.D., MHA, RN Assistant Chief, Medical Facilities Dr. Edd Rhoades Medical Director Emergency Systems___________________________ Managers and Supervisors Dale Adkerson Administrative Program Manager – EMS Division Grace Pelley Administrative Program Manager – Trauma and Systems Development Division Daniel Whipple Trauma Coordinator Xana Howard Trauma Registrar Staff Heather Cox EMS Administrator Chris Dew EMS Administrator Linda Dockery Administrative Assistant David Graham EMS Administrator Rashonda Hagar Administrative Assistant Dean Henke EMS Administrator Brandee Keele Quality and Survey Analyst Martin Lansdale Epidemiologist Jamie Lee Quality and Survey Analyst James Rose Statistical Research Specialist Judy Staley Administrative Assistant Lori Strider EMS Administrator Yang Wan Statistical Research Specialist Jennifer Woodruff EMS Administrator Marva Williamson Trauma Fund Coordinator 2 Foreward This annual report is compiled and published in accordance with Oklahoma Statute, Title 63, Section 1-2511. -

Bankruptcy Forms

11-15463-shl Doc 1440 Filed 02/27/12 Entered 02/27/12 20:33:01 Main Document In re: American Eagle Airlines, Inc. Pg 31 of 168 Case No. 11‐15469 Exhibit F1 ‐ Trade Payables Name Address City, State & Zip Claim Amount Disputed Contingent Unliquidated 1204 HOTEL OPERATING LLC DBA MCM ELEGANTE SUITES 4250 ABILENE TX 79606 $530.15 RIDGEMONT DR 1371500 ONTARIO INC THE TIRE TERMINAL 1750 MISSISSAUGA ON L4W 1J3 $1,244.88 BRITANNIA ROAD 1859 HISTORIC HOTELS LTD. DBA HILTON HOBBY AIRPORT 8181 HOUSTON TX 77061 $667.04 AIRPORT BLVD 35‐43 36TH STREET CORP DBA STUDIO SQUARE CATERING 35‐ LONG ISLAND CITY NY 11106 $4,783.33 43 36TH STREET 37‐10 HOTEL OPERATING COMPANY DBA HOLIDAY INN LAGUARDIA CORONA NY 11368 $1,078.91 AIRPORT 3710 114TH ST 4300 EAST FIFTH AVENUE LLC DBA 4300 VENTURE 6729 LLC DEPT L‐ COLUMBUS OH 43260 $59,392.69 2645 4300 EAST FIFTH AVENUE LLC 4131 EAST FIFTH AVENUE COLUMBUS OH 43219 X X Undetermined 44 NEW ENGLAND MANAGEMENT COMPANY DBA HILTON GARDEN INN JFK 14818 JAMAICA NY 11430 $2,861.72 134TH ST 752‐6172 CANADA INC $69.66 A & R FOOD SERVICE AMERICAN AIRLINES ‐ JFK/LGA FLUSHING NY 11371 $5,909.84 MARINE AIR TERMINAL BLD 81 A & V REBUILDING INCORPORATED 8211 S ALAMEDA ST LOS ANGELES CA 90001 $350.00 A A DELIVERY SERVICE PO BOX 76559 NOLANVILLE TX 76559 $5,705.00 A C ROSWELL LLC DBA LA QUINTA INN ROSWELL 200 E ROSWELL NM 88201 $2,282.94 19TH ST A E PETSCHE COMPANY PO BOX 910195 DALLAS TX 75391 $150.00 A H OFFICE COFFEE SERVICES 1151 ROHLWING RD ROLLING MEADOWS IL 60008 $3,500.70 A&M MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS LLC PO BOX 43552‐1277 PERRYSBURG OH 43552 $9,965.84 A+ AIRPORT SHUTTLE, INC.