Echtzeitmusik. the Social and Discursive Contexts of a Contemporary Music Scene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Capitalism and The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Capitalism and the Production of Realtime: Improvised Music in Post-unification Berlin A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Music by Philip Emmanuel Skaller Committee in Charge: Professor Jann Pasler, Chair Professor Anthony Burr Professor Anthony Davis 2009 The Thesis of Philip Emmanuel Skaller is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii DEDICATION I would like to thank my chair Jann Pasler for all her caring and knowledgeable feedback, for all the personal and emotional support that she has given me over the past year, and for being a constant source of positive inspiration and critical thinking! Jann, you are truly the best chair and mentor that a student could ever hope for. Thank you! I would also like to thank a sordid collection of cohorts in my program. Jeff Kaiser, who partook in countless discussions and gave me consistent insight into improvised music. Matt McGarvey, who told me what theoretical works I should read (or gave me many a contrite synopsis of books that I was thinking of reading). And Ben Power, who gave me readings and perspectives from the field of ethnomusicology and (tried) to make sure that I used my terminology clearly and consciously and also (tried) to help me avoid overstating or overgeneralizing my thesis. Lastly, I would like to dedicate this work to my partner Linda Williams, who quite literally convinced me not to abandon the project, and who's understanding of the contemporary zeitgeist, patient discussions, critical feedback, and related areas of research are what made this thesis ultimately realizable. -

Germany at Sxsw 2018 Guide

GUIDE GERMANY AT SXSW 2018 MARCH 9–18 AUSTIN, TEXAS CONTENTS WUNDERBAR 2018 INTRODUCTION 4 STATE OF MIND – STARTUP GERMANY 10 SMARTER CITIES & TECHNOLOGY 12 NEW TECHNOLOGIES & NEW INDUSTRIES 14 NEW MEDIA & NEW WORK 16 INTERNATIONAL CULTURE TECH DAY 18 WUNDERBAR – MULTIFACETED GERMAN MUSIC SCENE 20 BLOCKHAIN & THE MUSIC INDUSTRY 22 GERMAN ARTISTS AT SXSW 24 FESTIVALS & CONFERENCES 2018/19 30 EXHIBITORS & DELEGATES 41 PARTNERS 89 DETAILED INDEX 108 MAP OF AUSTIN 111 FIND OUT EVERYTHING ABOUT THE GERMAN DELEGATES, BANDS AND EVENTS GERMANY AT SXSW 2018 — WUNDERBAR 3 GREETINGS FROM PROFESSOR BRIGITTE ZYPRIES DIETER GORNY FEDERAL MINISTER FOR ECONOMIC AFFAIRS AND ENERGY CHAIRMAN OF THE INITIATIVE MUSIK ADVISORY BOARD The annual South by Southwest (SXSW) Welcome to WUNDERBAR! This year our festival in Austin has become one of the WUNDERBAR presentations at SXSW again most acclaimed gatherings of artists, cre- include impressive offerings from the wide ators, and startups. I am therefore pleased array of creative activities in the German digi- that Germany will be represented at SXSW tal, startup, film, and music industries. With 2018 with one of the largest international over one thousand conference participants delegations. This is proof of the strength of and musicians attending in 2018, Germany the German cultural and creative industries. is again ranked among the top five interna- tional participants at SXSW. We will greet The cultural and creative industries will you and other guests from around the world play an increasingly important role in the at our trade show stand and at German Haus, economy of the future. The boundaries of which is just five walking minutes away from traditional industries, such as automotive the Austin Convention Center. -

Jazzzeitung 10/2002 Oktober

27. Jahrgang Nr. 10-02 www.jazzzeitung.de Oktober 2002 B 07567 PVSt/DPAG Mit Festivalzeitung! Entgelt bezahlt Jazzin’ the Night Club 10 Jahre Jazz im Bayerischen Hof Jazzzeitung Mit Jazz-Terminen ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft aus Bayern, Hamburg, Brunnstraße 23 93053 Regensburg Mitteldeutschland ISSN 1618-9140 und dem Rest E 2,05 der Republik berichte farewell portrait label portrait dossier Viel Nu, wenig Jazz: Mo’Vibes 2002 Nach Hause geflogen: Lionel Hampton Zwischen den Kulturen: Nguyên Lê Austria Akzente: Quinton aus Wien Auf Tour in Mitteldeutschland S. 3 S. 11 S. 13 S. 17 S. 22–23 Liebe Leserinnen, liebe Leser, als die letzte Jazzzeitung produziert wur- de, standen gerade Teile Regensburgs unter Wasser, noch ahnte man nicht, wel- che verheerenden Ausmaße die Über- schwemmungen an der Elbe noch anneh- men würden. Nachdem wir über Berichte unserer Mitarbeiter in Dresden hautnah miterleben mussten, welche Schäden die Flutwelle anrichtete, beschloss die Re- daktion, sich dem Spendenaufruf unserer Schwesterzeitschrift „neue musikzei- tung“ für die Jazz-, Rock- und Popabtei- lung der Musikhochschule für Musik in Dresden, „Carl Maria von Weber” anzu- schließen. Diese ist im Untergeschoss der Hochschule untergebracht, entspre- chend verheerend waren die Schäden durch das Hochwasser (mehr auf Seite 23). Die Jazzzeitung ist unter die Preisstifter gegangen. Einmal im Jahr vergeben wir künftig zusammen mit der Sparda-Bank Baden-Württemberg und der Kulturge- sellschaft Musik und Wort die „German Jazz Trophy – A life for Jazz”. Preisträger 2002 ist kein Geringerer als Paul Kuhn (mehr auf Seite 2)! Das Jazzengagement des Münchner Ho- tels Bayerischer Hof geht ins zehnte Jahr. Das feiern die relativ frisch gebackenen und dennoch erfolgreichen Konzertveran- stalter mit einem einwöchigen Festival. -

It's All Good

SEPTEMBER 2014—ISSUE 149 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM JASON MORAN IT’S ALL GOOD... CHARLIE IN MEMORIAMHADEN 1937-2014 JOE • SYLVIE • BOBBY • MATT • EVENT TEMPERLEY COURVOISIER NAUGHTON DENNIS CALENDAR SEPTEMBER 2014 BILLY COBHAM SPECTRUM 40 ODEAN POPE, PHAROAH SANDERS, YOUN SUN NAH TALIB KWELI LIVE W/ BAND SEPT 2 - 7 JAMES CARTER, GERI ALLEN, REGGIE & ULF WAKENIUS DUO SEPT 18 - 19 WORKMAN, JEFF “TAIN” WATTS - LIVE ALBUM RECORDING SEPT 15 - 16 SEPT 9 - 14 ROY HARGROVE QUINTET THE COOKERS: DONALD HARRISON, KENNY WERNER: COALITION w/ CHICK COREA & THE VIGIL SEPT 20 - 21 BILLY HARPER, EDDIE HENDERSON, DAVID SÁNCHEZ, MIGUEL ZENÓN & SEPT 30 - OCT 5 DAVID WEISS, GEORGE CABLES, MORE - ALBUM RELEASE CECIL MCBEE, BILLY HART ALBUM RELEASE SEPT 23 - 24 SEPT 26 - 28 TY STEPHENS (8PM) / REBEL TUMBAO (10:30PM) SEPT 1 • MARK GUILIANA’S BEAT MUSIC - LABEL LAUNCH/RECORD RELEASE SHOW SEPT 8 GATO BARBIERI SEPT 17 • JANE BUNNETT & MAQUEQUE SEPT 22 • LOU DONALDSON QUARTET SEPT 25 LIL JOHN ROBERTS CD RELEASE SHOW (8PM) / THE REVELATIONS SALUTE BOBBY WOMACK (10:30PM) SEPT 29 SUNDAY BRUNCH MORDY FERBER TRIO SEPT 7 • THE DIZZY GILLESPIE™ ALL STARS SEPT 14 LATE NIGHT GROOVE SERIES THE FLOWDOWN SEPT 5 • EAST GIPSY BAND w/ TIM RIES SEPT 6 • LEE HOGANS SEPT 12 • JOSH DAVID & JUDAH TRIBE SEPT 13 RABBI DARKSIDE SEPT 19 • LEX SADLER SEPT 20 • SUGABUSH SEPT 26 • BROWN RICE FAMILY SEPT 27 Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps with Hutch or different things like that. like things different or Hutch with sometimes. -

Music in B Erlin September 7–14, 2015 Gendarmenmarkt Square, Berlin

BETCHART EXPEDITIONS Inc. 17050 Montebello Road, Cupertino, CA 95014-5435 MUSIC IN B ERLIN September 7–14, 2015 Gendarmenmarkt square, Berlin Dear Traveler, Throughout its history, Berlin has been one of Germany’s musical epicenters. Eighteenth-century Berlin was considered the “Golden Age” for music making (corresponding with the coronation of Frederick II, himself a musician), and many important musical figures have lived and worked in this dynamic city, including Johann Joachim Quantz, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Felix Mendelssohn, and Richard Strauss. In the 20th century, the fall of the wall turned Berlin into one of the most musically endowed places in the world—orchestras previously divided between east and west were now merged under the banner of one, unified city. This special program thoroughly immerses travelers in Berlin’s musical heritage, history, and artistic ambitions with a six-night exploration of the city combined with the opportunity to enjoy three private performances by superbly talented local chamber musicians, played at historic venues. Carefully-crafted, these personalized concerts will explore the themes of Baroque, classical, and romantic musical styles. While evenings will be spent appreciating Berlin’s classical music traditions, daytime excursions will introduce you to this splendid city, where history greets Demetrios Karamintzas and Kim Barbier perform a visitors at every turn. Delve into the city’s cultural institutions, including the famed private concert Pergamon Museum, with its unrivaled collection of ancient art and architecture, Cover: Brandenburg Gate and the Gemaldegalerie, home to one of the world’s greatest collections of 13th- to 18th-century European paintings. Berlin’s Jewish Museum, Cold War-era Brandenburg Gate, and Checkpoint Charlie all speak to the city’s tumultuous 20th-century history. -

Dissertation Committee for Michael James Schmidt Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Michael James Schmidt 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Michael James Schmidt certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Multi-Sensory Object: Jazz, the Modern Media, and the History of the Senses in Germany Committee: David F. Crew, Supervisor Judith Coffin Sabine Hake Tracie Matysik Karl H. Miller The Multi-Sensory Object: Jazz, the Modern Media, and the History of the Senses in Germany by Michael James Schmidt, B.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2014 To my family: Mom, Dad, Paul, and Lindsey Acknowledgements I would like to thank, above all, my advisor David Crew for his intellectual guidance, his encouragement, and his personal support throughout the long, rewarding process that culminated in this dissertation. It has been an immense privilege to study under David and his thoughtful, open, and rigorous approach has fundamentally shaped the way I think about history. I would also like to Judith Coffin, who has been patiently mentored me since I was a hapless undergraduate. Judy’s ideas and suggestions have constantly opened up new ways of thinking for me and her elegance as a writer will be something to which I will always aspire. I would like to express my appreciation to Karl Hagstrom Miller, who has poignantly altered the way I listen to and encounter music since the first time he shared the recordings of Ellington’s Blanton-Webster band with me when I was 20 years old. -

THE CULTURE and MUSIC of AMERICAN CABARET Katherine Yachinich

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Music Honors Theses Music Department 5-2014 The ulturC e and Music of American Cabaret Katherine Anne Yachinich Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/music_honors Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Yachinich, Katherine Anne, "The ulturC e and Music of American Cabaret" (2014). Music Honors Theses. 5. http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/music_honors/5 This Thesis open access is brought to you for free and open access by the Music Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 THE CULTURE AND MUSIC OF AMERICAN CABARET Katherine Yachinich A DEPARTMENT HONORS THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC AT TRINITY UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR GRADUATION WITH DEPARTMENTAL HONORS DATE 04/16/2014 Dr. Kimberlyn Montford Dr. David Heller THESIS ADVISOR DEPARTMENT CHAIR Dr. Sheryl Tynes ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT FOR ACADEMIC AFFAIRS, CURRICULUM AND STUDENT ISSUES Student Copyright Declaration: the author has selected the following copyright provision (select only one): [X] This thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which allows some noncommercial copying and distribution of the thesis, given proper attribution. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, California 94305, USA. [ ] This thesis is protected under the provisions of U.S. Code Title 17. Any copying of this work other than “fair use” (17 USC 107) is prohibited without the copyright holder’s permission. -

The Electronic Music Scene's Spatial Milieu

The electronic music scene’s spatial milieu How space and place influence the formation of electronic music scenes – a comparison of the electronic music industries of Berlin and Amsterdam Research Master Urban Studies Hade Dorst – 5921791 [email protected] Supervisor: prof. Robert Kloosterman Abstract Music industries draw on the identity of their locations, and thrive under certain spatial conditions – or so it is hypothesized in this article. An overview is presented of the spatial conditions most beneficial for a flourishing electronic music industry, followed by a qualitative exploration of the development of two of the industry’s epicentres, Berlin and Amsterdam. It is shown that factors such as affordable spaces for music production, the existence of distinctive locations, affordability of living costs, and the density and type of actors in the scene have a significant impact on the structure of the electronic music scene. In Berlin, due to an abundance of vacant spaces and a lack of (enforcement of) regulation after the fall of the wall, a world-renowned club scene has emerged. A stricter enforcement of regulation and a shortage of inner-city space for creative activity in Amsterdam have resulted in a music scene where festivals and promoters predominate. Keywords economic geography, electronic music industry, music scenes, Berlin, Amsterdam Introduction The origins of many music genres can be related back to particular places, and in turn several cities are known to foster clusters of certain strands of the music industry (Lovering, 1998; Johansson and Bell, 2012). This also holds for electronic music; although the origins of techno and house can be traced back to Detroit and Chicago respectively, these genres matured in Germany and the Netherlands, especially in their capitals Berlin and Amsterdam. -

David Sylvian As a Philosopher Free Download

DAVID SYLVIAN AS A PHILOSOPHER FREE DOWNLOAD Leonardo Vittorio Arena | 66 pages | 28 Feb 2016 | Mimesis International | 9788869770029 | English | MI, Italy ISBN 13: 9788869770029 It would be another six months before the Nine Horses album would surface. But ours is a way of life. Secrets of the Beehive made greater use of acoustic instruments and was musically oriented towards sombre, emotive ballads laced with string arrangements by Ryuichi Sakamoto and Brian Gascoigne. Sylvian and Fripp's final collaboration was the installation Redemption — Approaching Silence. The two artists lived in New Hampshire where they had two children. For me, that David Sylvian as a Philosopher an exploration of intuitive states via meditation and other related disciplines which, the more I witnessed free-improv players at work, appeared to be crucially important to enable a being there in the moment, a sustained alertness and receptivity. Keep me signed in. Lyrics by David Sylvian. Forgot your details? By Stephen Holden, 16 December David Sylvian. Venice by Christian Fennesz Recording 3 editions published in in Undetermined and English and held by 26 WorldCat member libraries worldwide. Martin Power. Following Dead BeesSylvian released a pair of compilation albums through Virgin, a two-disc retrospective, Everything and Nothingand an instrumental collection, Camphor. He has said about his process, "With Blemish I started each day in the studio with a very simple improvisation David Sylvian as a Philosopher guitar. His father Bernard was a plasterer by trade, his mother Sheila a housewife. Home Learning. Never one to conform to commercial expectations, Sylvian then collaborated with Holger Czukay. -

The Olympic Art Competitions Were Performed

he Olympic Art competitions were performed THOMAS, GENZMER and TUUKANEN. And in two Tseven times between 1912 and 1948. From cases even the 'Olympic' compositions are said to 153 possible medals altogether only 124 (i.e. 81%) be available on record: were distributed. The percentages in the differ- ent categories are: Architecture 84%, Literature 1. Rudolf SIMONSEN (1889-1947), ,,Sinfonien 69%, Painting 84%, and Sculpture 84%. In Music - Nr. 2 a-moll, (1921) Hellas, Grondal/Dan. 39 were possible, but there were only 17 medals, ISA DA CORD 3701371" 5 gold, 6 silver and 6 bronze. The percentage in 2. Josef ŠUK "Ins Neue Leben op. 35c Marsch music is 43.5%, by far the worst result within the z.T. Sokolfest": In this case the catalogue five art categories. offers three recordings, two Czech Su- Altogether five medals (two gold, two sil- praphon (Kubelik/Tschech.Philh. Prag ver and one bronze) were distributed in the five KoSup 01911-2/Neumann/Tschech. music competitions in Stockholm 1912, Antwerp Philh. Prag KoSup 00624-4) and one 1920, Paris 1924, Amsterdam 1928 and Los Ange- American (Kunzel/Cincinnati Pops Orch les 1932. Then the situation seemed to improve. InaTe 80122). In Berlin and London 1948 twelve music medals were awarded (three gold, four silver and five The catalogue does, however, not mention the bronze). names of BARTHÉLEMY, MONIER, RIVA, HÖFFER, However, none of these works has left a trace KRICKA, BIANCHI, WEINZWEIG, LAURICELLA, TURSKI in the history of music; none has gained any repu- or BRENE. But there are. available recordings of tation, because their quality was not at all Olym- compositions by Kurt THOMAS (e.g. -

Notes from the Underground: a Cultural, Political, and Aesthetic Mapping of Underground Music

Notes From The Underground: A Cultural, Political, and Aesthetic Mapping of Underground Music. Stephen Graham Goldsmiths College, University of London PhD 1 I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: …………………………………………………. Date:…………………………………………………….. 2 Abstract The term ‗underground music‘, in my account, connects various forms of music-making that exist largely outside ‗mainstream‘ cultural discourse, such as Drone Metal, Free Improvisation, Power Electronics, and DIY Noise, amongst others. Its connotations of concealment and obscurity indicate what I argue to be the music‘s central tenets of cultural reclusion, political independence, and aesthetic experiment. In response to a lack of scholarly discussion of this music, my thesis provides a cultural, political, and aesthetic mapping of the underground, whose existence as a coherent entity is being both argued for and ‗mapped‘ here. Outlining the historical context, but focusing on the underground in the digital age, I use a wide range of interdisciplinary research methodologies , including primary interviews, musical analysis, and a critical engagement with various pertinent theoretical sources. In my account, the underground emerges as a marginal, ‗antermediated‘ cultural ‗scene‘ based both on the web and in large urban centres, the latter of whose concentration of resources facilitates the growth of various localised underground scenes. I explore the radical anti-capitalist politics of many underground figures, whilst also examining their financial ties to big business and the state(s). This contradiction is critically explored, with three conclusions being drawn. First, the underground is shown in Part II to be so marginal as to escape, in effect, post- Fordist capitalist subsumption. -

Programmatik Und Spezifischen Konzeption

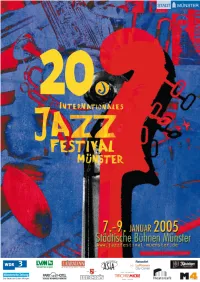

Internationales Jazzfestival Münster Ein Festival von Partnern AStA der Universität Münster Parkhotel Schloss Hohenfeld Beck’s Pianohaus Micke Köstritzer Schwarzbierbrauerei ReiseArt Lufthansa City Center LVM Versicherungen Münster Stadt Münster, Kulturamt M4 Media Theatercafé Möbelspedition Laarmann Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln Münstersche Zeitung Weitere Förderer: Audizentrum Münster, Auto-Krause GmbH Communauté Francaise de Belgique Deutsche Bahn AG Globe, Service Provider Michael Klein Multimediadesign, Ansgar Bolle Pellegrino Ritter, Illustrator Medienpartner des Internationalen Jazzfestivals Münster GRUSSWORT as Jazzfestival hat Geburtstag: Wenn sich An- rern des Internationalen Jazzfestivals, die das Festival fang Januar 2005 für drei Tage Jazzmusikerinnen zum Teil seit Jahren begleiten. Es sind dies das Parkho- Dund -musiker der Spitzenklasse in Münster prä- tel Schloss Hohenfeld, die LVM-Versicherungen, das sentieren, feiert das Internationale Jazzfestival Münster Reisebüro ReiseArt Lufthansa CityCenter, die Spedition seinen 20. Geburtstag. Laarmann, die Münstersche Zeitung, die Brauereien Köstritzer und Becks, das Theatercafé, das Pianohaus Es war 1979, Carl Carstens wurde zum 5. Bundespräsi- Micke sowie die Agentur M4 Media. denten gewählt und löste Walter Scheel ab, es war die Zeit von Jimmy Carter und Leonid Breshnev, von Gorle- Dieser Kreis von Partnern leistet auch finanzielle ben und Salt-II-Abkommen. Der Film „Die Blechtrom- Unterstützung, bringt aber auch im erheblichen Umfang mel“ lief in den Deutschen Kinos an, die erste Compu- Know-How aus der Wirtschaft in das Festival und ins- tersprache wurde entwickelt. In Münster legte sich die besondere die Kommunikation des Festivals ein. Eine Aufregung nach der ersten Skulpturenausstellung - das solche Zusammenarbeit ist beispielhafte Public-Private- Stadtmuseum wurde gegründet. Partnership. In dieser Zeit entschloss sich der AStA der Universität Münster, einen Jazztag im Schlossgarten auszurichten Ein weiterer Dank gilt gerade beim Jubiläumsfestival und legte damit den Grundstein für das Jazzfestival.