The Acceptance and Usage Intention of Menstrual Underwear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panties of Legend

Kris Newton [email protected] The Power to Change the World is in your Panties YOU are a regular, panty-wearing slob like the rest of us. You have exactly three layers – the same number as everybody else, and nearly half as many as a burrito. You've got a few distinguishing Features that make you stand out, one or two Fetishes that occasionally make you spout comical nosebleeds, and a Big Dream in your heart. You live a normal, boring life, but this roleplaying game isn't about that. That would be stupid. It's about the way your life changes when you don the Panties of Legend. THE PANTIES OF LEGEND are mysterious underwear of unknown origin. Only a handful of the panties are known to exist (and if the phrase "handful of the panties" excites you, you're playing the right game). When you sublimate sexual urges, your panties charge up like an overwrought metaphor for burgeoning sexuality, granting you superhuman Powers. Nothing can stop you when your panties are magical... except for your Rivals. YOUR RIVALS wear the other Panties of Legend. Despite their rarity, Panties of Legend probably belong to all your best friends and worst enemies at work or school. Go figure. When a Rival is near, you feel a tingle in your panties. Don't be confused; that's your body's natural way of telling you to defeat your Rivals and increase your magical powers. The only way to safely gain Panty Power is to make other Panties of Legend explode. PANTIES OF LEGEND GAIN POWER WHEN YOU'RE TURNED ON, BUT EXPLODE WHEN THEY'RE OVERCHARGED. -

European Union

OFFICE OF TEXTILES AND APPAREL (OTEXA) Market Reports Textiles, Apparel, Footwear and Travel Goods European Union The following information is provided only as a guide and should be confirmed with the proper authorities before embarking on any export activities. Import Tariffs The EU is a customs union that provides for free trade among its 28 member states--Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, The Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and The United Kingdom. The EU levies a common tariff on imported products entered from non-EU countries. By virtue of the Belgium-Luxembourg Economic Union (BLEU), Belgium and Luxembourg are considered a single territory for the purposes of customs and excise. The United Kingdom (UK) withdrew from the EU effective February 1, 2020. During the transition period, which ends on December 31, 2020, EU law continues to be applicable to and in the UK. Any reference to Member States shall be understood as including the UK where EU law remains applicable to and in the UK until the end of the transition period according to the Withdrawal Agreement (OJ C 384 1, 12.11.2019, p. 1). EU members apply the common external tariff (CET) to goods imported from non-EU countries. Import duties are calculated on an ad valorem basis, i.e., expressed as a percentage of the c.i.f. (cost, insurance and freight) value of the imported goods. EU: Tariffs (percent ad valorem) on Textiles, Apparel, Footwear and Travel Goods HS Chapter/Subheading Tariff Rate Range (%) Yarn -silk 5003-5006 0 - 5 -wool 5105-5110 2 - 5 -cotton 5204-5207 4 - 5 -other vegetable fiber 5306-5308 0 - 5 -man-made fiber 5401-5406/5501-5511 3.8 - 5 ....................... -

Press Kit the History of French Lingerie at the Sagamore Hotel Miami Beach

LINGERIE FRANCAISE EXHIBITION PRESS KIT THE HISTORY OF FRENCH LINGERIE AT THE SAGAMORE HOTEL MIAMI BEACH Continuing its world tour, the Lingerie Francaise exhibition will be presented at the famous Sagamore Hotel Miami Beach during the Art Basel Fair in Miami Beach from November 29th through December 6th, 2016. Free and open to all, the exhibition showcases the ingeniousness and creativity of French lingerie which, for over a century and a half, has been worn by millions of women worldwide. The exhibition is an immersion into the collections of eleven of the most prestigious French brands: AUBADE, BARBARA, CHANTELLE, EMPREINTE, IMPLICITE, LISE CHARMEL, LOU, LOUISA BRACQ, MAISON LEJABY, PASSIONATA and SIMONE PÉRÈLE. With both elegance and playfulness, the story of an exceptional craft unfolds in a space devoted to contemporary art. The heart of this historic exhibition takes place in the Game Room of the Sagamore Hotel. Beginning with the first corsets of the 1880’s, the presentation documents the custom-made creations of the 1930’s, showcases the lingerie of the 1950’s that was the first to use nylon, and culminates with the widespread use of Lycra® in the 1980’s, an epic era of forms and fabrics. This section focuses on contemporary and future creations; including the Lingerie Francaise sponsored competition’s winning entry by Salima Abes, a recent graduate from the university ESMOD Paris. An exclusive collection of approximately one hundred pieces will be exhibited, all of them emblematic of a technique, textile, and/or fashion innovation. A selection of landmark pieces will trace both the history of intimacy and the narrative of women’s liberation. -

Exporting Sleepwear to Europe 1. Product Description

Exporting sleepwear to Europe Last updated: 10 October 2018 The European market for sleepwear is growing. Most imports originate from developing countries. The middle to high-end segments offer you the most opportunities. Focus on design and quality to appeal to these consumers. Using sustainable fabrics and providing comfort can also give you a competitive advantage. Contents of this page 1. Product description 2. Which European markets offer opportunities for exporters of sleepwear? 3. Where is consumer demand located? 4. What is the role of European production in supplying European demand? 5. Which countries are most interesting in terms of imports from developing countries? 6. What role do exports play in supplying European demand? 7. What is the effect of real private consumption expenditure on European demand? 8. What trends offer opportunities on the European market for sleepwear? 9. What requirements should sleepwear comply with to be allowed on the European market? 10. What competition do you face on the European sleepwear market? 11. Through what channels can you put sleepwear on the European market? 12. What are the end-market prices for sleepwear? 1. Product description Sleepwear includes: adult onesie – all-in-one sleep suits worn by adults, usually cotton, similar to an infant onesie or children's blanket sleeper baby-doll – short, sometimes sleeveless, loose-fitting nightgown or negligee for women, generally designed to resemble a young girl's nightgown bathrobe – serving both as a towel and an informal garment, usually made -

Confidential

CONFIDENTIALFOR INTERNAL USE ONLY CONFIDENTIAL FOR INTERNAL� USE ONLY VISUALCONFIDENTIALFOR MERCHANDISINGINTERNAL USE ONLY GUIDE intimates & sleep : how-to library CONFIDENTIALFOR INTERNAL USE ONLY CONFIDENTIALFOR INTERNAL USE ONLY LOW SCOPE STORES INTIMATES & SLEEP - LOW SCOPE STORES HOW-TO POG types POG Grid will not be provided in this VMG. Use the MyDevice for Store Specific POGs. Intimates POGs are tied differently to allow for greater flexibility in cross-merchandising Intimates & Sleep. Z4 Review details below: Z4 NATIONAL BRAND NATIONAL Hybrid POG (tied to fixture): Z3 AUDEN P2 - Newest version of a POG (e.g. Core Bras). Styles are tied to a particular fixture – to allow for M2 M1 flexibility within the fixture. P1 P3 - Use both VMG and POG to execute. Refer to the POG to pull styles, but use the VMG for specific merchandising details (e.g.: color flow, hardware and ISM location). Flex POG (tied to one or multiple fixtures): D4 - Styles are tied to one POG (e.g. Auden Bralettes) to allow for flexible merchandising within the D3 entire shop. - Refer to the VMG for merchandising direction. D2 Traditional POG: D1 - Use the POG (e.g. Packaged Panties) to merchandise presentations. Z2 STARS ABOVE Z1 COLSIE - Refer to VMG for inspirational photos, if available. POG TITLES ON ADJACENCY POG TYPE STEPS TO MERCHANDISE 1. USE STORE SPECIFIC ADJACENCY & MYDEVICE FOR STORE SPECIFIC POG BALI, PARAMOUR, WARNERS, SEASONAL, CORE BRA HYBRID 2. PLAN POG LOCATION ALSO USING VMG PRODUCT FLOW MAP WALL, PLUS, PF BRA COMBO (SMALL FORMAT) 3. USE VMG FOR HOW-TO PAGES ON HARDWARE POSITION, MERCHANDISING AND ISM POSITIONING 1. -

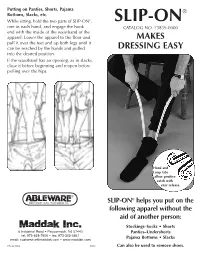

SLIP-ON®, SLIP-ON One in Each Hand, and Engage the Hook CATALOG NO

Putting on Panties, Shorts, Pajama ® Bottoms, Slacks, etc. While sitting, hold the two parts of SLIP-ON®, SLIP-ON one in each hand, and engage the hook CATALOG NO. 73839-0000 end with the inside of the waistband of the apparel. Lower the apparel to the floor and MAKES pull it over the feet and up both legs until it can be reached by the hands and pulled DRESSING EASY into the desired position. If the waistband has an opening, as in slacks, close it before beginning and reopen before pulling over the hips. Hook and Loop tabs allow positive catch with easy release. SLIP-ON® helps you put on the following apparel without the aid of another person: Stockings–Socks • Shorts 6 Industrial Road • Pequannock, NJ 07440 Panties–Undershorts tel: 973-628-7600 • fax: 973-305-0841 email: [email protected] • www.maddak.com Pajama Bottoms • Slacks 973839002 0803 Can also be used to remove shoes. INSTRUCTIONS Engage the gear-like teeth to make SLIP-ON® As shown in Figure 3, keep the hook ends operable. As shown in Figure 1, hold engaged with the stocking and separate SLIP-ON® in one hand and insert the two parts of SLIP-ON®, holding one in the hook ends inside the each hand. Pull the stocking over the heel top opening of stocking. and up the leg to the point where it can Hold SLIP-ON® in the be reached by hand and adjusted to the left hand if you are desired position. putting the stocking Caution: When using with sheer stockings on the left foot; in the engage hook ends with reinforced top band right hand for the right to avoid rupturing the sheer knit. -

Fancy Dress Party

Fancy Dress Party Barbara and Alison want to find a way to get Albert, Barbara’s husband to admit he is a cross- dresser. They hit on the perfect solution, a fancy dress party to which everyone, well nearly everyone, has to wear a costume which involves wearing silky lingerie and stockings underneath. 1 Alison decided she would go and see her sister Barb at the beginning of October. They planned to go shopping again at the Mall, it was so much fun last time they went flashing on the up escalators. Alison had intended to take her 18 year old son Mike with her but he protested that he had too much college work to do and he could the washing and ironing whilst she was away. 2 She trusted him to do the washing and ironing as she knew he loved ironing all her silky slips but she wondered what else he might get up to whilst she was away for the weekend. 3 So Alison travelled up to Cheshire, on her own. When she got there she greeted both Barbara, and her husband Arnold, with a peck on the cheek. After asking how her journey was Arnold excused himself and went upstairs to read an ebook on his new Kindle, a birthday present from Barbara. The two sisters sat down with a cup of coffee and rolled back the years. They recalled the flashing they had done on their last shopping trip to the Mall. This triggered a memory for Barbara about when she was about 16 and still dancing. -

Private Lessons a Photo Story by Andrea Slip

Private Lessons A photo story by Andrea Slip 1 | P a g e Lesson01 Mike was a little nervous as he stood outside the brown front door on a Sunday afternoon. His mum had arranged for him to have some A-level revision lessons with a Miss Loren, a friend of hers who used to be a maths teacher. He didn’t quite know what to expect. He knocked on the door. Within a few moments the door opened. Mike had to try very, very hard not to let his jaw hit the floor. A lady opened the door to Mike. “You must be Mike, pleased to meet you, do come in, I am Sophie Loren” said Sophie shaking his hand. Mike recovered as he stared in amazement at the lady dressed in a cream silk dress. As she put her brown high heels on the step her button up dress split at the front to reveal both a cream lace edged slip and possibly the hint of a lacy stocking top. Miss Loren, Sophie, looked vaguely familiar, but he couldn’t quite place where from. 2 | P a g e Lesson02 Earlier that Sunday Sophie was dressing in her bedroom. She remembered that this afternoon that the son of her co-worker Alison was coming round for his first maths revision lesson. She had also established with Alison in the staffroom at work that he was the shelf stacker that had seen her up- skirt flash and had “helped” her find the toilet when her skirt had accidently fallen down at the Supermarket. -

Undergarments : Extension Circular 4-12-2

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska 4-H Clubs: Historical Materials and Publications 4-H Youth Development 1951 Undergarments : Extension Circular 4-12-2 Allegra Wilkens Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/a4hhistory Part of the Service Learning Commons Wilkens, Allegra, "Undergarments : Extension Circular 4-12-2" (1951). Nebraska 4-H Clubs: Historical Materials and Publications. 124. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/a4hhistory/124 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 4-H Youth Development at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska 4-H Clubs: Historical Materials and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Jan. 1951 E.G. 4-12-2 o PREPARED FOR 4-H CLOTHrNG ClUB GIRLS EXTENSION SERVICE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE COOPERATING A W. V. LAMBERT, DIRECTOR C i ( Undergarments for the Well Dressed 4-H Girl Allegra Wilkens The choosing or designing of the undergarments that will make a suitable foundation for her costume is a challenge to any girl's good taste. She may have attractive under- wear if she is wise in the selection of materials and careful in making it or in choosing ready-made garments. It is not the amount of money that one spends so much as it is good judgment in the choice of styles, materials and trimmings. No matter how beautiful or appropriate a girl's outer garments may be, she is not well dressed unless she has used good judgment in making or selecting her under - wear. -

Women's Lingerie-Ladies Undergarments (Bra & Panties)

Manufacturing Plant, Detailed Project Report, Profile, Business Plan, Industry Trends, Market Research, Survey, Manufacturing Process, Machinery, Raw Materials, Feasibility Study, Investment Opportunities, Cost and Revenue, Plant Economics, Production Schedule, Working Capital Requirement, Plant Layout, Process Flow Sheet, Cost of Project, Projected Balance Sheets, Profitability Ratios, Break Even Analysis www.entrepreneurindia.co Introduction Hosiery industry is an ancient industry in the field of textile industry having very good potential in domestic market and also in the export market. There is increasing market demand for hosiery undergarments for its various advantages. Cotton undergarments are widely used by all classes of people because of its good absorbency, cheaper prices and ready availability. These foundation garments are used by the people throughout the year under different climatic conditions. It is presumed that there will be no problem in marketing of knitted undergarments of good quality. www.entrepreneurindia.co Ladies innerwear (Bra and panties) is the highest growing apparel item across all income groups and exclusive boutiques have popped up in all places. Nothing cramps the style faster than ill-fitting and uncomfortable undergarments. Thus, innerwear are not only made attractive, but also comfortable and practical. Top stylists unchain their creativity by inventing fabulous new forms and materials which make ladies innerwear even more sexy, eccentric and wild, without leaving out elegance. www.entrepreneurindia.co There has been an increase in demand for innovative, comfort-oriented undergarments and lately, many women are forgoing those fussy lingerie designs for simple, uncomplicated ladies undergarments. In addition to keeping outer garments from soiling, ladies innerwear are worn for a variety of reasons: warmth, comfort and hygiene being the most common. -

2010 ANNUAL Reportpage 1

2010N AN UAL REPORT 0526_cov.indd 2 4/7/11 10:30 AM COMPARISON OF 5 YEAR CUMULATIVE TOTAL RETURN* Among The Warnaco Group, Inc., the Russell 2000 index, the S&P Midcap 400 index, the Dow Jones US Clothing & Accessories index $250 and the S&P Apparel, Accessories & Luxury Goods index COMPARISONCOMParisON OF OF 5YEAR 5-YEar CCUMULATIVEUMULatiVE TO TOTALtaL RE TRETURN*Urn* e Warnaco Group, Inc. compared to select indices $250 $200 250 250 $200 $150 200 200 $150 150 150 $100 $100 100 100 $50 $50 50 50 $0 0 0 $0 3/06 6/06 9/06 3/07 6/07 9/07 3/08 6/08 9/08 3/09 6/09 9/09 3/10 6/10 9/10 12/05 12/06 12/07 12/08 12/09 12/10 12/05 3/06 6/06 9/06 12/06 3/07 6/07 9/07 12/07 3/08 6/08 9/08 12/083/096/09 9/09 12/09 3/10 6/10 9/10 12/10 e Warnaco Group, Inc. Russell 2000 S&P MidCap 400 Dow Jones U.S. Clothing & Accessories The Warnaco Group, Inc. Russell 2000 S&P Apparel, Accessories & Luxury Goods *$100 invested on 12/31/05 in stock or index, including reinvestment of dividends. Fiscal year ending December 31. S&P Midcap 400 Dow Jones US Clothing & Accessories Copyright © 2011 S&P, a division of e McGraw-Hill Companies Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2011 Dow Jones & Co. All rights reserved. S&P Apparel, Accessories & Luxury Goods *$100 invested on 12/31/05 in stock or index, including reinvestment of dividends. -

Lady Lyka Intimate 'N' Apparels, New Delhi

We introduce ourselves as one of the leading manufacturers, exporters and suppliers of wide range of ladies and kids undergarments. Made from 100% cotton, these garments are highly comfortable and skin friendly. - Profile - We New Deal Export, are a Pvt. Limited Company engaged in the manufacturing, export and supply of an attractive and comfortable range of ladies & kids undergarments. The vast assortment of lingeries we offer are both skin friendly and designer. Our range include ladies panties, kids under garments, brassies, shorts. Incepted in the year 1995, our company has incorporated three factors of quality, comfort and hygiene in the undergarments we manufacture. We work under the able guidance of Mr. Naveen Arora, who acquired degree in the field of fashion, textile and pattern designing from England. His understanding of fashion trends, consumer demand and focused approach further assist us enhance our global presence. Further, constant research and innovative skills of our team of designers also back in providing soft, appealing and wearable undergarments in both standard and customized patterns to clients. Kids Undergarments: We have with us a wide assortment of Kids Undergarments that are available in attractive colors and designs. These are fabricated using high-grade fabric and threads and are soft, sweat absorbent as well as skin-friendly and provide complete comfort to the child . The undergarments are provided in different sizes and colors to meet the demand of individuals. Cotton All Over Printed Kids Undergarments Vest Ans Bloomer Kids Undergarments Kids Undergarments Hipster Panties: Manufacturer & Exporter of a wide range of products which include Hipster Panties such as Cotton Hipster Panties, Seamless Hipster, Lace Hipster Panties and Womens Hipster Panties.