Forest Essays (Level 7-12)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2011 The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861 Cessna R. Smith Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Cessna R., "The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861" (2011). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 258. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.258 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861 by Cessna R. Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: William L. Lang, Chair David A. Horowitz David A. Johnson Barbara A. Brower Portland State University ©2011 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how the pursuit of commercial gain affected the development of agriculture in western Oregon’s Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue River Valleys. The period of study begins when the British owned Hudson’s Bay Company began to farm land in and around Fort Vancouver in 1825, and ends in 1861—during the time when agrarian settlement was beginning to expand east of the Cascade Mountains. Given that agriculture -

An Historical Perspective of Oregon's and Portland's Political and Social

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 3-14-1997 An Historical Perspective of Oregon's and Portland's Political and Social Atmosphere in Relation to the Legal Justice System as it Pertained to Minorities: With Specific Reference to State Laws, City Ordinances, and Arrest and Court Records During the Period -- 1840-1895 Clarinèr Freeman Boston Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, and the Public Administration Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Boston, Clarinèr Freeman, "An Historical Perspective of Oregon's and Portland's Political and Social Atmosphere in Relation to the Legal Justice System as it Pertained to Minorities: With Specific Reference to State Laws, City Ordinances, and Arrest and Court Records During the Period -- 1840-1895" (1997). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4992. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6868 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Clariner Freeman Boston for the Master of Science in Administration of Justice were presented March 14, 1997, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVAL: Charles A. Tracy, Chair. Robert WLOckwood Darrell Millner ~ Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL<: _ I I .._ __ r"'liatr · nistration of Justice ******************************************************************* ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY by on 6-LL-97 ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Clariner Freeman Boston for the Master of Science in Administration of Justice, presented March 14, 1997. -

ISADORE and MARGARET ARQUETT ST. MARTIN

ISADORE and MARGARET ARQUETT ST. MARTIN ISADORE ST. MARTIN MARGARET ARQUETTE ST. MARTIN Isadore and Margaret Arquette St. Martin 2 St. Martin 1987 Printed for Luther St. Martin by Carson Printing All right reerved. Written by Luther St. Martin From his research work and memories of his early life in the St. Martin family. Dedicated to L. A. (Luch) St. Martin Transcribed by Frances Durrell Isadore and Margaret Arquette St. Martin 3 Isadore St. Martin Born November 6, 1842 at Nisqually, Washington Died March 10, 1910 Margaret Arquett Born April 29, 1846 at St. Paul, Oregon Died 1933 Married at The Dalles, Oregon in 1864 Isadore and Margaret Arquette St. Martin 4 CHAPTER I EARLY LIFE OF ISADORE ST. MARTIN Isadore St. Martin was a top hand with horses and oxen. As a teamster, he hauled freight around The Dalles, Oregon. With his pack horses he packed gold from Canyon City and other mines. One of his many jobs was hauling ice from the ice caves north of White Salmon, Washington to The Dalles, Oregon. He was a Scout for the Army in the southern Oregon Indian wars. The author does not know at what other places he served while in the Army. The family lived in two places in the period of 1874 to 1876. St. Martin and his wife and daughters lived on a five acre tract of land in Carson, Washington. The boys lived in the cabin on the homestead until 1876. The house was located on what is called the top of the hill. This house was built by St. -

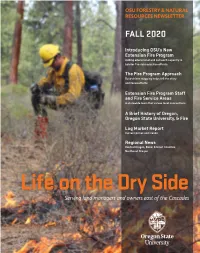

Life on the Dry Side, Fall 2020, PDF Edition

OSU FORESTRY & NATURAL RESOURCES NEWSLETTER NOTE: PagesFALL may be rearranged2020 and duplicated to accommodate need. See Pages window. Introducing OSU's New Extension Fire Program Adding educational and outreach capacity to bolster fire risk reduction efforts The Fire Program Approach Data-driven mapping helps tell the story and focus efforts Extension Fire Program Staff and Fire Service Areas A statewide team that values local connections A Brief History of Oregon, Oregon State University, & Fire Log Market Report Current prices and trends Regional News Central Oregon, Baker & Grant Counties, Northeast Oregon Life on the Dry Side Serving land managers and owners east of the Cascades Life on the Dry Side OSU FORESTRY & NATURAL RESOURCES NEWSLETTER Serving land managers and owners east of the Cascades Contributors IN THIS ISSUE John Punches Extension Forester in Union, Umatilla, and Wallowa Counties 3 Log Market Report 10507 N McAlister Rd, Current prices and trends La Grande, OR 97850 (541) 963-1061 [email protected] 4 OSU’s New Extension Fire Program Adding educational and outreach capacity to bolster fire risk reduction efforts Jacob Putney Extension Forester in Baker and Grant Counties 5 Baker & Grant County News 2600 East Street, Forest service considering amendment to the “21 in. Rule” Baker City, Oregon 97814 (541) 523-6418 [email protected] 6 The Fire Program Approach Data-driven mapping helps tell the story and focus efforts Carrie Berger 9 Northeast Oregon News Fire Program Manager NE Oregon National Forests awarded restoration funding 133 Richardson Hall Corvallis OR 97331 541-737-7524 10 Extension Fire Program Staff [email protected] and Fire Service Areas A statewide team that values local connections Thomas Stokely 14 A Brief History of Oregon, Oregon State Forestry and Natural Resources Agent, in Warm Springs, Crook, University, and Fire Deschutes, and Jefferson Counties 800 SW, SE Airport Way, Bldg. -

1880 Census: Volume 4. Report on the Agencies of Transportation In

ON :STEAM NA VIGArrION lN '.J.'Irn UNITED sr_rA 'l~ES. JJY SPECIAI..1 AGlt:.NT. i <65.'~ TABI"'E OF CONTENTS. Page. I .. BTTF.H OF TR A ~81\fITTAI.J ••• ~ - •• -- •••.•• - •• - •• - •• - • - •••• --- ••• - •••• -- •.•.••.••••••• - •••••• - ••• -- •••.•••••• - ••.• -- •••••••••• - • v C IIAPTBR. !.-HISTORY OF STEAM NA YI GA TION IN THE UNI'l'l~D STA TES. Tug EAHLY INVENTORS .•••••••••••••••••.••••••••••••••.••..••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••..•••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 1-4 11.ECOHDS OF CONSTRUCTION ..••••••••••.••••••••••••••••••...•••.••••••••••.••••••.•••••.•••••.••••••••.•••••••••....•••••••• 4,5 I~ec:1piti.1lation ......•••..........• , .......••.•......... -................•................••.•...•..••..•........•...... 5 LOCAL INTERESTS ••••. - ••••• - ••••••••••.•••••••.••. - •••..•• - ..•• - •••.••••.•.• -- ••••.•.••..••••.•••.•.• - •••••.•..• - •••••••.•• - • 5-7 Report of the Secretary of the 'rrensnry in 1838 .. ,. .................................................................... 5, 6· Report of the Secretary of tho 'l'reasnry in 1851. ....................................................................... • fi,7 INSPECTIONS OF STEAll! VESSELS ••••••..•••••••••••••• - ••••••••••. - •.••••••••••••••••••••••••.•.••••.••••••••••.•••..•••••••• 7 UNITED STATI~S AND l~ORBIGN TONNAGE ••••••••••• -- •••••••..•••..•••••••••••• -- • -- •••••• - ••••• ·--· .••• -· ••••••••••.•••••• - • 7,8 GRouP r.-NEw li::NGLANn sTA'l'Es •••••••••••••••••••.••••••••••••••••••.••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.•••••.••••••••••••••• H-11 Building -

Oregon Biography Index

FE1'75 B7 cop. Oregon Biography Index Bibliographic Series Number 11 1976 Oregon State University Press Corvallis, Oregon OREGON BIOGRAPHY INDEX Edited by Patricia Brandt and Nancy Guilford Bibliographic Series Number 11 Corvallis Oregon State University 1976 © 1976 Oregon State University Press ISBN 0-87071-131-8 OREGON BIOGRAPHY INDEX INTRODUCTION Oregon Biography Index is intended to serve primarily as a starting point in locating biographies of Oregonians. We have indexed 47 historical volumes which are either entirely devoted to biographies or have large self-contained biographical sections. The profiles in the books vary widely in accuracy and detail. Birth dates of biographees range from Revolutionary times to the first quarter of the 20th century. Not all important or famous Oregonians are included, yet there are many lesser known persons. Most of the articles also include information on parents and other ancestors, children, relatives of a spouse or some- times even friends and colleagues. Rather than trying to decide how fully to index a biographical sketch, we have chosen to include only the name given at the head of each article. All biographies in each volume have been indexed, including those of non-Oregonians. As a result, there are scores of Washingtonians listed, along with some citizens of Idaho, Montana and the mountain states. Arrangement of the index is alphabetical by name of person. Ordinarily, spelling has been accepted as found, and names are as complete as possible within space limitations. Every effort has been made to compare similar names and bring together all biographies of an individual. In spite of our efforts, a few people may be listed in more than one place. -

MEN of CHAMPOEG Fly.Vtr,I:Ii.' F

MEN OF CHAMPOEG fly.vtr,I:ii.' f. I)oI,I,s 7_ / The Oregon Society of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution is proud to reissue this volume in honor of all revolutionaryancestors, this bicentennialyear. We rededicate ourselves to theideals of our country and ofour society, historical, educational andpatriotic. Mrs. Herbert W. White, Jr. State Regent Mrs. Albert H. Powers State Bicentennial Chairman (r)tn of (]jjainpog A RECORD OF THE LIVES OF THE PIONEERS WHO FOUNDED THE OREGON GOVERNMENT By CAROLINE C. DOBBS With Illustrations /4iCLk L:#) ° COLD. / BEAVER-MONEY. COINED AT OREGON CITY, 1849 1932 METROPOLITAN PRESS. PUBLISHERS PORTLAND, OREGON REPRINTED, 1975 EMERALD VALLEY CRAFTSMEN COTTAGE GROVE, OREGON ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS MANY VOLUMES have been written on the history of the Oregon Country. The founding of the provisional government in 1843 has been regarded as the most sig- nificant event in the development of the Pacific North- west, but the individuals who conceived and carried out that great project have too long been ignored, with the result that the memory of their deeds is fast fading away. The author, as historian of Multnomah Chapter in Portland of the Daughters of the American Revolution under the regency of Mrs. John Y. Richardson began writing the lives of these founders of the provisional government, devoting three years to research, studying original sources and histories and holding many inter- views with pioneers and descendants, that a knowledge of the lives of these patriotic and far-sighted men might be preserved for all time. The work was completed under the regency of Mrs. -

Carolyn Patricia Mcaleer for the Degree of Master of Arts in Applied Anthropology Presented on November 14, 2003

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Carolyn Patricia McAleer for the degree of Master of Arts in Applied Anthropology presented on November 14, 2003. Title: Patterns from the Past: Exploring Gender and Ethnicity through Historical Archaeology among Fur Trade Families in the Willamette Valley of Oregon. Abstract Approved: Redacted for privacy David R. Brauner This thesis examines archaeological material in order to explore gender and ethnicity issues concerning fur tradeera families from a settlement in the Willamette Valley, Oregon. Ethnohistorical information consisting of traders journals and travelers observations, as well as documentation from the Hudson's Bay Company, Catholic church records, and genealogical information helped support and guide this research. By using historical information as wellas archaeological material, this research attempted to interpret possible ethnic markers and gender relationships between husbands and wives among five fur tradeera families. Families of mixed ethnicity, including French Canadian, Native, Metis and American, settled the valley after 1828 bringing with them objects and activities characteristic of their way of life. Retired fur tradetrappers, of French Canadian and American decent, married either Metisor Native women. Of 53 identified families, four French Canadian/Native families have been chosen for this project,as well as one American settler, and his Native wife. Little is known about how these women interacted within their families or whether they maintained certain characteristics of their Native culture. It was hoped that these unique cultural dynamics might become evident through an analysis of the ceramic assemblages from these sites. Due to the extensive nature of the archaeological collections, and time constraints related to this thesis, only ceramics have been examined. -

W V V 8 25 2012.Pdf

Willamette Valley Voices: Connecting Generations In This Issue A Journal of Willamette Valley History This edition of Willamette Valley Voices: Connecting Generations is the first of the Willamette Volume 1 Summer 2012 Number 1 Heritage Center’s new biannual publication. The goal of the journal is to provide a showcase for scholarly writing pertaining to History and Heritage in the Oregon’s Willamette Valley, south of Portland, written by scholars, students, heritage professionals and historians - professional and amateur. The Importance of Public Space as Community Anchors Its purpose is to promote historical scholarship focused on the communities of the area. Each edition is Joy Sears themed to orient authors and readers to widely varied and important topics in Valley history. 4 Willamette Valley Voices’ first edition shares articles about Public Spaces. Public spaces, both built and Dancing its Way into your Heart: Cottonwoods Ballroom 1930-1960 natural, anchor the Valley’s communities and shape and inform community identities. Identity-making Toni Rush and Jim Creighton around community anchors is an important way to reinvigorate city centers and downtowns. Civic 9 institutions and public spaces help create vibrant towns and destinations, as well as serve as catalysts for revitalizing the neighborhoods and areas around them. Salem School Names Fritz Juengling The articles in this first issue vary greatly in topic, but generally seem to fall into three areas: Those that 18 focus on history specific to a city, town or place - “Dancing its Way into your Heart: Cottonwoods Oregon State Insane Asylum: A Sanctuary Ballroom 1930-1960” by Toni Rush & Jim Creighton and “Salem School Names” by Fritz Juengling; Dianne Huddleston topics that have a largely statewide emphasis, though they also have broader implications - “Oregon 31 State Insane Asylum: A Sanctuary” by Diane Huddleston and “The First Women to Cross the Continent by Covered Wagon, Welcomed by Dr. -

BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Published by the Archives of British Columbia in Cooperation with the British Columbia Historical Association

THE BRITISH I COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY JANUARY, 1946 r’ “ BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Published by the Archives of British Columbia in cooperation with the British Columbia Historical Association. EDITOR. W. KAYE LAMB. The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. ASSOCIATE EDITOR. WILLARD E. IRELAND. Provincial Archives, Victoria, B.C. ADVISORY BOARD. J. C. GOODFELLOW, Princeton. T. A. RICKARD, Victoria. W. N. SAGE, Vancouver. Editorial communications should be addressed to the Editor. Subscriptions should be sent to the Provincial Archives, Parliament Buildings, Victoria, B.C. Price, 50c. the copy, or $2 the year. Members of the British Columbia Historical Association in good standing receive the Quarterly without further charge. Neither the Provincial Archives nor the British Columbia Historical Association assumes any responsibility for statements made by contributors to the magazine. The Quarterly is indexed in Faxon’s Annual Magazine Subject-Index. BRITISH COLUMBIA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY “Any country worthy of a future should be interested in its past.” VOL. X. VICTORIA, B.C., JANUARY, 1946. No. 1 CONTENTS. PAGE. Steamboating on the Fraser in the ‘Sixties. By Norman R. Hacking - The Fire Companies of Old Victoria. By F. W. Laing and W. Kaye Lamb 43 NOTES AND COMMENTS: British Columbia Historical Association 7? Constitution of the British Columbia Historical Association 82 Okanagan Historical Society — 85 Kamloops Museum Association 86 James Buie Leighton: Cariboo Pioneer 86 Historical Committee, B.C. Division, Canadian Weekly Newspapers Association — 87 Contributors to this Issue 88 Jo The Colonel Moody, the first steamer registered at New Westminster. Built at Victoria in 1859. The Lady of the Lake, built for service on Anderson Lake by Chapman & Company in 1860. -

Pre-Settlement Forests of Southwest Washington: Witness Statements

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.04.425257; this version posted January 5, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. – more citizen science from Poulsbo, WA – Pre-Settlement Forests of Southwest Washington: Witness Statements Tom Schroeder Abstract In the mid-nineteenth century overland immigration into western Washington State passed through lands bracketed by the lower Columbia River and the Pacific Ocean. Witness trees from the region’s first GLO surveys (General Land Office), which preceded settlement, are used to reconstruct the composition, character, and distribution of the region’s natural forests. As such, this investigation augments a similar study of early forests around Puget Sound, situated immediately to the north (Schroeder, 2019). A retrospective species map is constructed from locational information from more than thirty-five thousand witness trees; accompanying tree diameters elucidate size differences by species and geographic locales. Three principal forest types were noted: western hemlock in the rainy western hills, with some Sitka spruce near the coast; Douglas-fir with woodland tree species in the rain-shadowed central plains; and hemlock/Douglas-fir/redcedar mixtures on the lower flanks of the Cascade Range. Although the majority of trees were small or medium in size, a significant fraction was large. All forest types displayed significant amounts of old growth, as judged by screening witness trees against a quantitative model. -

Historic Capitols of Oregon

-_._- - , I OREGON STATE LIBRARY I -IF( OREGON L. i �'IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII1111111111111111111111111111, 3 4243 00026551 8 1.40.::1 1 I JUL 11 .\� � :;:: STAT� �IBRARY HISTORIC CAPITOLS . OF OREGON '� .. " an illustrated chronology , ; .. " researched and written by William Allen Bentson with an introduction by Senator Mark O. Hatfield a publication of the OREGON LIBRARY FOUNDATION Salem, Oregon 97310-0642 ,{iF,: L. i , 40 c:l. : :.:: .:" :�:. B<.:- n t�, 0 n, lrJ i i 1 :l am (=l '/ 1 <:" r, " Histo�ic capitols of 0�e8on .:: . • � ::�: :��: , L - j - i!-Ck 1. IF' (, 1"1 " t" \ 1- 1 -\ :_I - ;:_- :t IT1 (1 1 -\ h:'-- n t �_ (, n , __ __ _ _ _ - _ _ _,: - -\ c (, {- 1.1 r- (.' 9 '-' II � l t- u � - listorlC C� HISTORIC CAPITOLS OF OREGON . an illustrated chronology researched and written by William Allen Bentson with an introduction by Senator Mark o. Hatfield a publication of the OREGON LIBRARY FOUNDATION Salem, Oregon 97310-0642 - Published by theOregon Library Foundation OregonState Library Building Salem, Oregon 97310·0642 State Library Board of Trustees Foundation Board of Directors Don Oakes, Chair Molly Kohnstamm. Ontario, Oregon President Larry Dalrymple, Vice-Chair Portland, Oregon Boardman, Oregon PeggyOliver KarenLytle Bla ha Vice President Lake Oswego, Oregon Lake Oswego, Oregon AudreyLane Carey Nina Cleveland LaGrande, Oregon Secretary-Treasurer NellieRipper Salem, Oregon North Bend, Oregon John Snider Wayne Robertson Medford, Oregon Hubbard, Oregon Jack Walsdorf Gail Schultz Portland, Oregon Portland, Oregon Author: William Allen Bentson, Major, A.U.S. Ret. Title: Historic Capitols of Oregon: An Illustrated Chronology ISBN: Oregon History Consultant: Cecil Edwards, Senate Historian Editor: Addie Dyal, Local History Specialist Original photography and photo copies: Alfred Jones, Salem, Oregon Original 1855 drawing: Murray Wade The third publication in the series Occasional Papers of the Oregon State Library.