The Voice of the Negro 1919

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How North Carolina's Black Politicians and Press Narrated and Influenced the Tu

D. SHARPLEY 1 /133 Black Discourses in North Carolina, 1890-1902: How North Carolina’s Black Politicians and Press Narrated and Influenced the Tumultuous Era of Fusion Politics By Dannette Sharpley A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors Department of History, Duke University Under the advisement of Dr. Nancy MacLean April 13, 2018 D. SHARPLEY 2 /133 Acknowledgements I am very grateful to have had the opportunity to write an Honors Thesis in the History Department. When I returned to school after many years of separation, I was prepared for challenging work. I expected to be pushed intellectually and emotionally. I expected to struggle through all-nighters, moments of self-doubt, and even academic setbacks. I did not, however, imagine that I could feel so passionate or excited about what I learned in class. I didn’t expect to even undertake such a large project, let alone arrive at the finish line. And I didn’t imagine the sense of accomplishment at having completed something that I feel is meaningful beyond my own individual education. The process of writing this thesis has been all those things and more. I would first like to thank everyone at the History Department who supports this Honors Distinction program, because this amazing process would not be possible without your work. Thank you very much to Dr. Nancy MacLean for advising me on this project. It was in Professor MacLean’s History of Modern Social Movements class that I became obsessed with North Carolina’s role in the Populist movement of the nineteenth, thus beginning this journey. -

African Americans at the College of William and Mary from 1950 to 1970

African Americans at the College of William and Mary from 1950 to 1970 By: Jacqueline Filzen 1 Introduction This paper investigates the admission policies and the experiences of the first African American students at the College of William and Mary between 1950 and 1970—the height of the civil rights era. During these tense times in American history African American emerged as leaders of social change by enrolling in institutions of higher learning such as William and Mary. In addition to exploring the experience of the first African Americans, this paper also explores the attitudes of students, faculty, and William and Mary’s administration to integration. African Americans graduated from American colleges as early as the 1820s. The first African Americans to receive a college degree included John Rosswumm, Edward Jones, and Lucius Twilight.1 These men went on to becoming successful newspaper editors, businessmen, and local politicians. Other African Americans joined their ranks and received college degrees between 1820 and 1900. “W.E.B. Dubois reported that 390 blacks had earned diplomas from white colleges and universities between 1865 and 1900”.2 Like “many of the nation’s most prestigious, predominantly white universities in the South—which did not admit any blacks until the 1950s or 1960s”3 the College of William and Mary did not admit an African American student until 1951. Its decision to admit an African American student was not due to the school’s support for integration. Rather this decision was taken to avoid any legal repercussions if the College had done otherwise. Furthermore the College only admitted its first African American student after much deliberation and consultation with the Board of Visitors and the Attorney General. -

Chance to Meet at Summit Delivery Lapel

■/. •’ ■ MONDAY, MARCH 1«, WB9 .Avcnce^Baily Net Press Run ’ The Weather rorodtet of 0. 8- Wasther ■areps Pikcni POtJRTBSN fljanrljpotpf lEuftitn^ the Week RNdiag March 14th, lt59. Increasing cinudtiHiss this 'eve- ■nj# Army and Natv Auxiliary! GENERAL - nlng, cloudy^ and'epM tonight. Low The Newcoawa Cluh..wUl meet Ramp Estimate, 12,895 In tIHi. Wedneaday Y »lr and Mid. tomorrow night , at • d'diock at will hold a public card party to -; ^ v About Town the Community T.- Memhei^. are night at 8 o’clock at the clubhouae ^ -f. Mesnbar of the Audit High In 8ds. Bolton St. Plan TV SERVICE iSureau of Ormlatton. reminded .to bring haU fo r the Dftya e O QK A OaO lManche$ter— A City of Village craty hat conioat; John Mather Chapter, Order of Mr». It « « ti* P«lme, p rtiM trA DeMoly. will hold a buatnesa meet- Not Completed Nights O iM a Pint Parte ot IUvle«‘. Women'* Bene Mancheater liodge of Maeons •mg tonight at 7 o’clock In the Ma- TEL. Ml a-54«3 (Ulaaained Adiecfislng on Pago 14) J^PRICE FIVE CENTS fit A m - t •«<> Irene Vinwk. abnlc Terrtple. A rehearsal of the No new development* are ex VOL. LXXVIII, NO. 141 (SIXTEEN PAGES) MANCHESTER. CONN., Tl^SD AY, MA^ffH 17, i#59 ndll hold a special meeting to- pected to come up'on the subjects j are coSielrmen of » committee laotTow night at 7:30 at the Ma Injtiitory degree will follow- the amnstna: for e pubttc c«wJ p«rty of Bolton St. floodiag end a pro-1 sonic Temple. -

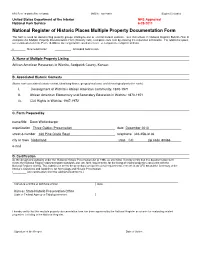

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior NPS Approved National Park Service 6-28-2011 National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items x New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing African American Resources in Wichita, Sedgwick County, Kansas B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. Development of Wichita’s African American Community: 1870-1971 II. African American Elementary and Secondary Education in Wichita: 1870-1971 III. Civil Rights in Wichita: 1947-1972 C. Form Prepared by name/title Deon Wolfenbarger organization Three Gables Preservation date December 2010 street & number 320 Pine Glade Road telephone 303-258-3136 city or town Nederland state CO zip code 80466 e-mail D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR 60 and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

Draft Dissertation

Dissention in the Ranks—Dissent Within U.S. Civil-Military Relations During the Truman Administration: A Historical Approach by David A. “DAM” Martin B.A. in History, May 1989, Virginia Military Institute M.A. in Military Studies—Land Warfare, June 2002, American Military University M.B.A., June 2014, Strayer University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Graduate School of Education and Human Development of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education January 19, 2018 Dissertation directed by Andrea J. Casey Associate Professor of Human and Organizational Learning The Graduate School of Education and Human Development of the George Washington University certifies that David A. “DAM” Martin has passed the final examination for the degree of Doctor of Education as of September 22, 2017. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Dissention in the Ranks—Dissent Within U.S. Civil-Military Relations During the Truman Administration: A Historical Approach David A. “DAM” Martin Dissertation Research Committee: Andrea J. Casey, Associate Professor of Human and Organizational Learning, Dissertation Director David R. Schwandt, Professor Emeritus of Human and Organizational Learning, Committee Member Stamatina McGrath, Adjunct Instructor, Department of History, George Mason University, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2018 by David A. Martin All rights reserved iii Dedication Dedicated to those who have Served honorably, Dissented when the cause was just, and paid dearly for it. iv Acknowledgments I want to thank my dissertation chair, Dr. Andrea Casey, for her outstanding advice and counsel throughout this educative journey. Thank you to my dissertation committee member, Dr. -

The US Army and the Omaha Race Riot of 1919

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: The US Army and the Omaha Race Riot of 1919 Full Citation: Clayton D Laurie, “The US Army and the Omaha Race Riot of 1919,” Nebraska History 72 (1991): 135-143. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1991USArmy.pdf Date: 3/01/2011 Article Summary: In 1919 Fort Omaha’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel Jacob Wuest, was unfamiliar with recent policies regarding the use of troops in domestic disorders. He hesitated when he was called upon to help put down the Omaha riot on September 28. The Army did eventually intervene, but only after three deaths and massive property damage that might have been avoided. Cataloging Information: Names: Newton D Baker, Edward P Smith, Agnes Loebeck, Will Brown, Jacob Wuest, P A Barrows, Leonard Wood Place Names: Omaha, Nebraska; Fort Omaha, Nebraska; Fort Crook, Nebraska; Camp Dodge, Iowa Keywords: Revised Statutes -

Warrior Writers Program Receives Geske Award Veterans Writing Workshop Recognized for Contribution to Literacy Pgs 2-3

IDEAS IN PROGRESS RAPPORT ISSUE 21 | WINTER 2019 WARRIOR WRITERS PROGRAM RECEIVES GESKE AWARD VETERANS WRITING WORKSHOP RECOGNIZED FOR CONTRIBUTION TO LITERACY PGS 2-3 The Healing Wall (excerpt) by Andy Gueck The family who searches the Wall to find a name, to put closure to the hole torn within their hearts every parent hopes that the telegram was wrong, That the name they seek is not there. As they reach the year, the day, the line, they find the name they so hoped was not there. Tears stream down her cheeks, weathered with age and sorrow, his eyes lose some of their luster in knowing the truth. The child seeking someone who was never there, touches a name, takes a shading, but receives no answers. Visitors to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. search for the names of loved ones and frequently copy the inscription as a memento. Photo by Chris Sommerich 1950s CHAUTAUQUA: PG 3 • GOVERNOR’S LECTURE RECAP: PG 4 • MEETING DWIGHT DAVID EISENHOWER II: PG 5 RECENT GRANTS: PG 8 • WELCOME NEW INTERNS: PG 9 • GRANT SPOTLIGHT: FORGIVENESS LINCOLN: PG 9 ONE BOOK ONE NEBRASKA: PAGE 9 • JACK CAMPBELL: PAGE 10 • NEW SPEAKERS BUREAU TOPICS NOW AVAILABLE: PG 12 ON WRITING by Sara Hollcroft NEBRASKA VETS FIND SUPPORT IN WRITING WORKSHOPS N NOVEMBER 9, NEBRASKA WARRIOR WRITERS RECEIVED THE 2019 JANE GESKE AWARD FROM THE NEBRASKA OCENTER FOR THE BOOK. THIS PROGRAM, A COOPERATIVE EFFORT BY HUMANITIES NEBRASKA WITH THE NEBRASKA WRITING PROJECT AND THE VETERANS ADMINISTRATION, GIVES MILITARY VETERANS AND ACTIVE DUTY PERSONNEL RAPPORT ACCESS TO FREE COACHING FROM PROFESSIONAL WRITING INSTRUCTORS. -

The American Reaction to the Atomic Bomb: 1945-1946

UWEC Atomic Reaction The American Reaction to the Atomic Bomb: 1945-1946 Blum, Philip James 3/5/2013 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author. Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... i Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1 The Dawning of a New Era ................................................................................................................... 3 Moral Capacity……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 American Public Opinion in the Immediate Aftermath .............................................................................. 5 Religious Response ................................................................................................................................... 6 Racial Perspectives……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………13 World Government? .......................................................................................................................... 16 Government Transgressions……………………………………….............................................................................18 The Military is No Democracy…………………………………………………………………………………….………….…………22 Racial Perspectives…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….23 -

Neil Bush's Massive Usa Pedophile Network

NEIL BUSH'S MASSIVE USA PEDOPHILE NETWORK Neil Mallon Bush 4 South West Oak Drive Unit 1 Houston, TX 77056-2063 Phone numbers: 713-552-0882 713-850-1288 The brother of George W. Bush, Neil is another evil Satanist running the biggest pedophile network in the USA currently. He MUST be stopped, he MUST be punished, since he (and lots of other high-level Satanists) operates his crime empire with impunity and always has had immunity from prosecution by the FBI and the rest of the FEDS. Many, many other little kids will suffer INTOLERABLE, EXCRUCIATING sexual agony and torture that their little bodies are not ready for, and will be scared and traumatized for the rest of their lives because of sick perverted fun these monsters enjoy by inflicting on these innocent little children, some of which are even used in secret Satanic sacrifices, and are brutally murdered, all for the sickening pleasure of these evil perverts. All of the Senate, and just about all of the Congress, and Federal Attorneys, and high-ranking military officers are involved in this Illuminati death cult. If you just sit there doing nothing, nothing will be stopped. Check out what happens at your local Masonic Temple or Scottish Rite Temple between tomorrow (Halloween) and November 1st. Every sheriff department and every police department has an imbedded agent who's job it is to get arrested and charged Satanists, and Freemasons off the hook, having their charges dropped quickly once they find out these criminals are a Satanist or a Mason. People Neil may know Ned Bush Pierce G Bush Elizabeth D Andrews Ashley Bush REPUBLICAN PARTY PEDOPHILES LIST * Republican mayor Thomas Adams of Illinois charged with 11 counts of disseminating child pornography and two counts of possession of child pornography. -

Michigan State University Cynthia Rose Goldstein

w ' “W”M”~~~w :2 THE PRESS COVERAGE-OF THE _ . e ENTRANCE 0F JACKIE ROBIN-SON ' ~ INTO BASEBALL AS THE Fl-‘RSTBLACK . i .15: if; . Thesis for the Degree of M. A.- § - MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY CYNTHIA ROSE GOLDSTEIN . ._ 1973‘ . I .‘ d“ T, I ' . a o c < . ‘ v v ~T . ' . ' . _ .3. _ _ " C. ,' O . .‘4- ‘_ ', .I. __ .. ,v ' ' . - .' {.- ,‘. ..-.' ...'_- ‘ . - '. J _ . ’ '1: :. 4:0- . ~ _H. ,1 ' — ' ' K ‘ ' - - " .I» ' ' - .-- , . ..-,.‘ - 4' ~ .. 7:“-‘t- -'~* - vra O; ‘ - ------ y-*_-.1’-v. l 1.. ‘ ’ .’ o - -,‘ . , . y..' ' . c .0 ‘ ' . ‘ . - ' . '. z. ’ , v'r'-'o‘. g-‘u'd‘ "'o “v. '3'.{.:.'.._ . ' - .. '7 . ... g . ' 9 'c- . , 0 ';-."C v.1 1' ' '05.; . ,. -- . ,r. ‘:'.:. ‘- 1 'n - ¢;. -o'."q' .“)‘.'.J‘:‘.;:'. ’J:11“.'J._":f; :n\ '.".1- LGfo:n¢n‘-' " \I’v:‘::-< {:1’-"ru1fM-:'l‘t‘-m I PLACE ll RETURfl BOX to roman this checkout from your "cord. \ TO AVOID FINES Wm on Of More dd. (10.. I DATE, DUE DATE DUE DATE our»: 3 I . ‘l * \ ~ APR 3309 T a v—fi—j H; : Pm 201 Two \\“ r usu Is An Nflmaflvo Action/Equal oppomnny Imuuuon WW9 ABSTRACT THE PRESS COVERAGE OF THE ENTRANCE OF JACKIE ROBINSON INTO BASEBALL AS THE FIRST BLACK BY Cynthia Rose Goldstein In 1945, a revolution began to take place in baseball. Branch Rickey, owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, a team in the National League, signed Jackie Robinson, a player from the Kansas City Monarchs, a team in the Negro American League, to a contract with the Dodgers. This study examines the press coverage of the entrance of Jackie Robinson into baseball as the first black. -

Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889-1918

vv THIRTY YEARS OF LYNCHING IN THE UNITED STATES 1889-1918 T>» Published by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Notional Offict 70 Fifth Avenue, New York APRIL, 1919 PRICE - FIFTY CENTS LYNCHING PAMPHLETS* President Wilson’s Lynching and Mob Violence Pronouncement T (of July 26, 1918). Lynchings of May, 1918, in Brooks and Lowndes Counties, Georgia; an investigation by the N. A. A. C. P.; 8 pages. The Massacre of East St. Louis ; an account of an Investigation by W. E. Burg- hardt Du Bois and Martha Gruening, for the N. A. A. C. P., illustrated, 20 pages, reprinted from The Crisis for September, 1917. The Burning of Ell Person at Memphis, Tenn. ; an account taken from the Memphis daily papers of May 22, 23, 24 and June 3, 1917; 4 pages. The Burning of Ell Person at Memphis, Tenn.; an investigation by James Weldon Johnson for the N. A. A. C. P.; reprinted from The Crisis for July, 1917; 8 pages. The Lynching of Anthony Crawford (at Abbeville, S. C., October 21, 1916). Article by Roy Nash (then) Secretary, N. A. A. C. P.; reprinted from the Independent for December, 1916; 4 pages, large size. Notes on Lynching in the United States, compiled from The Crisis, 1912; 16 pages. Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889-1918, April,fl919; 105 pages, fifty cents, f The Fight Against Lynching; Anti-Lynching Work of the National Asso- ciation for the Advancement of Colored People for the year 1918; April, 1919; 20 pages, ten cents. * Copies of the pamphlets listed may be obtained from the Secretary of the Association, t Through a typographical error, this publication was advertised in the Association’s annual report (for 1018 ) at fifteen cents instead of fifty cents. -

Congressional Record-House. 779

, 1922. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. _779 Otto W. Petry to be postmaste;: at Elk Lick; Pa., in place of The SPEAKER. Is there objection? Chl'istian S. Lichleiter. Incumbent's commission expi.~ed August Mr. KELLER. Mr. Speaker, I object. 7, 1921. Mr. MONDELL. Mr. Speaker, I mo-ve to dispense -with busi.. George E. Kemp to be postmaster at Philadelphl.1, Pa., in ness in order under the Calendar Wednesday rule. place of J. A. Thornton, removed. The SPEAKER. The question is on the motion of the gentle SOUTH CAROLINA, man from Wyoming to dispense with business in order under the Harry E. Dawson· to be postmaster at l\:Iount Pleasant, S. C., Calendar Wednesday rule. in place of W. T. Reynolds, jr., resigned. The question was taken, and the Speaker announced that in the opinion of the Chair two-thirds had voted in the affirmative. SOUTH DAKOTA. Mr:GARRETT of Tennessee. Mi·. Speaker, on that I demand Geneva l\1. Small to be postmaster at Lane, S Dak. Office a division. became presidential January 1, 1921. The House divided ; and there were-ayes 81, noes 52. TENNESSEE. Mr. l\10NDELL. Mr. Speaker, I make the point of order that Thomas W. Williams to be postmaster at Lucy, Tenn. Office there is no quorum present. became presidential April 1, 1921. The SPEAKER. The gentleman froin Wyoming makes the Daniel C. Ripley to be postmaster at Rogersville, Tenn., in point of order that there is no quorum present. Evidently there plnce of w·. B. Hale, deceased. is not. The Doorkeeper will close the doors, the Sergeant at Arms will notify absentees, and the Clerk will call the roll.