Black and Catholic Responses to the Second Ku Klux Klan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How North Carolina's Black Politicians and Press Narrated and Influenced the Tu

D. SHARPLEY 1 /133 Black Discourses in North Carolina, 1890-1902: How North Carolina’s Black Politicians and Press Narrated and Influenced the Tumultuous Era of Fusion Politics By Dannette Sharpley A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors Department of History, Duke University Under the advisement of Dr. Nancy MacLean April 13, 2018 D. SHARPLEY 2 /133 Acknowledgements I am very grateful to have had the opportunity to write an Honors Thesis in the History Department. When I returned to school after many years of separation, I was prepared for challenging work. I expected to be pushed intellectually and emotionally. I expected to struggle through all-nighters, moments of self-doubt, and even academic setbacks. I did not, however, imagine that I could feel so passionate or excited about what I learned in class. I didn’t expect to even undertake such a large project, let alone arrive at the finish line. And I didn’t imagine the sense of accomplishment at having completed something that I feel is meaningful beyond my own individual education. The process of writing this thesis has been all those things and more. I would first like to thank everyone at the History Department who supports this Honors Distinction program, because this amazing process would not be possible without your work. Thank you very much to Dr. Nancy MacLean for advising me on this project. It was in Professor MacLean’s History of Modern Social Movements class that I became obsessed with North Carolina’s role in the Populist movement of the nineteenth, thus beginning this journey. -

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “THAT OUR GOVERNMENT MAY STAND”: AFRICAN AMERICAN POLITICS IN THE POSTBELLUM SOUTH, 1865-1901 By LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Mia Bay and Ann Fabian and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “That Our Government May Stand”: African American Politics in the Postbellum South, 1865-1913 by LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO Dissertation Director: Mia Bay and Ann Fabian This dissertation provides a fresh examination of black politics in the post-Civil War South by focusing on the careers of six black congressmen after the Civil War: John Mercer Langston of Virginia, James Thomas Rapier of Alabama, Robert Smalls of South Carolina, John Roy Lynch of Mississippi, Josiah Thomas Walls of Florida, and George Henry White of North Carolina. It examines the career trajectories, rhetoric, and policy agendas of these congressmen in order to determine how effectively they represented the wants and needs of the black electorate. The dissertation argues that black congressmen effectively represented and articulated the interests of their constituents. They did so by embracing a policy agenda favoring strong civil rights protections and encompassing a broad vision of economic modernization and expanded access for education. Furthermore, black congressmen embraced their role as national leaders and as spokesmen not only for their congressional districts and states, but for all African Americans throughout the South. -

African Americans at the College of William and Mary from 1950 to 1970

African Americans at the College of William and Mary from 1950 to 1970 By: Jacqueline Filzen 1 Introduction This paper investigates the admission policies and the experiences of the first African American students at the College of William and Mary between 1950 and 1970—the height of the civil rights era. During these tense times in American history African American emerged as leaders of social change by enrolling in institutions of higher learning such as William and Mary. In addition to exploring the experience of the first African Americans, this paper also explores the attitudes of students, faculty, and William and Mary’s administration to integration. African Americans graduated from American colleges as early as the 1820s. The first African Americans to receive a college degree included John Rosswumm, Edward Jones, and Lucius Twilight.1 These men went on to becoming successful newspaper editors, businessmen, and local politicians. Other African Americans joined their ranks and received college degrees between 1820 and 1900. “W.E.B. Dubois reported that 390 blacks had earned diplomas from white colleges and universities between 1865 and 1900”.2 Like “many of the nation’s most prestigious, predominantly white universities in the South—which did not admit any blacks until the 1950s or 1960s”3 the College of William and Mary did not admit an African American student until 1951. Its decision to admit an African American student was not due to the school’s support for integration. Rather this decision was taken to avoid any legal repercussions if the College had done otherwise. Furthermore the College only admitted its first African American student after much deliberation and consultation with the Board of Visitors and the Attorney General. -

Building Networks: Cooperation and Communication Among African Americans in the Urban Midwest, 1860-1910

Building Networks: Cooperation and Communication Among African Americans in the Urban Midwest, 1860-1910 Jack S. Blocker Jr.* In the dramatic narrative of African-American history, the story of the post-Emancipation years begins in the rural South, where the rights won through postwar constitutional amendments gradually yield to the overwhelming forces of segregation and disfranchisement. During the First World War, the scene shifts to the metropolitan North, where many members of the rapidly growing southern-born migrant population develop a new, militant consciousness. Behind this primary narrative, however, lies another story. An earlier, smaller migration flow from South to North had already established the institutional and cultural foundations for the emergence of a national racial consciousness in postbellum America. Much of this crucial work took place in small and mid-size towns and cities. Some interpreters have seen the creation of a national racial consciousness as a natural and normal product of African heritage. This view, however, neglects the diverse origins and experiences of African Americans during the slavery years. “Alternatively,”writes historian Harold Forsythe, “we should consider that a distinctive national community developed from local roots during emancipation. Local associations of freedpeople, organized in families, neighborhood groupings, churches, [and] benevolent and fraternal orders, slowly developed into regional, statewide, and ultimately national consociations. This process of unification involved not only consciousness, but [also] institutional and power connections. It matured between 1909 and about 1925.”’The process of community-building can be seen clearly in the three states of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, which I call the Lower Midwest. On the eve of the Civil War, about 56,000 African Americans lived in the Lower Midwest. -

Chance to Meet at Summit Delivery Lapel

■/. •’ ■ MONDAY, MARCH 1«, WB9 .Avcnce^Baily Net Press Run ’ The Weather rorodtet of 0. 8- Wasther ■areps Pikcni POtJRTBSN fljanrljpotpf lEuftitn^ the Week RNdiag March 14th, lt59. Increasing cinudtiHiss this 'eve- ■nj# Army and Natv Auxiliary! GENERAL - nlng, cloudy^ and'epM tonight. Low The Newcoawa Cluh..wUl meet Ramp Estimate, 12,895 In tIHi. Wedneaday Y »lr and Mid. tomorrow night , at • d'diock at will hold a public card party to -; ^ v About Town the Community T.- Memhei^. are night at 8 o’clock at the clubhouae ^ -f. Mesnbar of the Audit High In 8ds. Bolton St. Plan TV SERVICE iSureau of Ormlatton. reminded .to bring haU fo r the Dftya e O QK A OaO lManche$ter— A City of Village craty hat conioat; John Mather Chapter, Order of Mr». It « « ti* P«lme, p rtiM trA DeMoly. will hold a buatnesa meet- Not Completed Nights O iM a Pint Parte ot IUvle«‘. Women'* Bene Mancheater liodge of Maeons •mg tonight at 7 o’clock In the Ma- TEL. Ml a-54«3 (Ulaaained Adiecfislng on Pago 14) J^PRICE FIVE CENTS fit A m - t •«<> Irene Vinwk. abnlc Terrtple. A rehearsal of the No new development* are ex VOL. LXXVIII, NO. 141 (SIXTEEN PAGES) MANCHESTER. CONN., Tl^SD AY, MA^ffH 17, i#59 ndll hold a special meeting to- pected to come up'on the subjects j are coSielrmen of » committee laotTow night at 7:30 at the Ma Injtiitory degree will follow- the amnstna: for e pubttc c«wJ p«rty of Bolton St. floodiag end a pro-1 sonic Temple. -

JUMPING SHIP: the DECLINE of BLACK REPUBLICANISM in the ERA of THEODORE ROOSEVELT, 1901—1908 a Thesis Presented to the Graduat

JUMPING SHIP: THE DECLINE OF BLACK REPUBLICANISM IN THE ERA OF THEODORE ROOSEVELT, 1901—1908 A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Mark T. Tomecko August, 2012 JUMPING SHIP: THE DECLINE OF BLACK REPUBLICANISM IN THE ERA OF THEODORE ROOSEVELT, 1901—1908 Mark T. Tomecko Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ ______________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Tracey Jean Boisseau Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ ______________________________ Department Chair Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Martin Wainwright Dr. George Newkome ______________________________ Date ii ABSTRACT Most analysts of black voting patterns in the United States have assumed that the first substantive abandonment of the Republican party by black voters occurred in the 1930s, when the majority of black voters embraced Franklin Roosevelt‘s New Deal. A closer examination, however, of another Roosevelt presidency – that of Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909) – demonstrates the degree to which black voters were already growing disenchanted with the Republicans in the face of what they viewed as uneven support and contradictory messages from the highest ranking Republican in the land. Though the perception of Theodore Roosevelt‘s relationship to black Americans has been dominated by his historic invitation of Booker T. Washington to dine with him at the White House in 1901, in fact even this event had assorted and complex meanings for Roosevelt‘s relationship to the black community. More importantly, his dismissal of black troops following a controversial shooting in southern Texas in 1906 – an event known as the Brownsville affair – set off a firestorm of bitter protest from the black press, black intellectuals, and black voters. -

In Search of Helen Maria Chesnutt (1880-1969), Black Latinist

New England Classical Journal Volume 48 Issue 1 Pages 110-121 5-14-2021 In Search of Helen Maria Chesnutt (1880-1969), Black Latinist Michele Valerie Ronnick Wayne State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/necj Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Ronnick, Michele Valerie (2021) "In Search of Helen Maria Chesnutt (1880-1969), Black Latinist," New England Classical Journal: Vol. 48 : Iss. 1 , 110-121. https://doi.org/10.52284/NECJ/48.1/article/ronnick This Announcement is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Classical Journal by an authorized editor of CrossWorks. In Search of Helen Maria Chesnutt (1880-1969), Black Latinist MICHELE VALERIE RONNICK Abstract: Classical scholars have begun to delineate the dynamic pattern of black classicism. This new subfield of the classical tradition involves the analysis of the creative response to classical antiquity by artists as well as the history of the professional training in classics of scholars, teachers and students in high schools, colleges and universities. To the first group belongs Helen Maria Chesnutt (1880-1969). Born in Fayetteville, NC, Chesnutt was the second daughter of acclaimed African American novelist, Charles W. Chesnutt (1858-1932). She earned her B.A. from Smith College in 1902 and her M.A. in Latin from Columbia University in 1925. She was a member of the American Philological Association and the Classical Association of the Middle West and South. Her life was spent teaching Latin at Central High School in Cleveland, OH. -

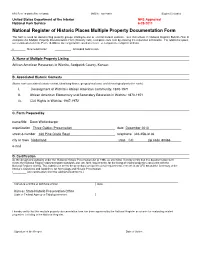

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior NPS Approved National Park Service 6-28-2011 National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items x New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing African American Resources in Wichita, Sedgwick County, Kansas B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. Development of Wichita’s African American Community: 1870-1971 II. African American Elementary and Secondary Education in Wichita: 1870-1971 III. Civil Rights in Wichita: 1947-1972 C. Form Prepared by name/title Deon Wolfenbarger organization Three Gables Preservation date December 2010 street & number 320 Pine Glade Road telephone 303-258-3136 city or town Nederland state CO zip code 80466 e-mail D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR 60 and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

Archival Expert Assignment Sheet

Melissa Range Lawrence University [email protected] Archival expert assignment sheet This term, you will be in charge of leading one class as the “archival expert.” Your assignment is simple: I want you to read nineteenth century newspapers published by African American editors. Using two of the library’s electronic databases—African American Newspapers and/or Accessible Archives—you will make use of digital archives to provide historical context for the day’s reading. Here’s what to do for prep work, step by step: • On the date you’re signed up to be the archival expert, look at when the writer published their works. (So, for example: Frances Ellen Watkins Harper published Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects in 1855.) • Determine a location that is relevant to the writer, if possible. For Harper, this could be Baltimore (where she grew up), Philadelphia (where she lived and worked as an adult), or Boston (where she frequently lectured). • Now choose a newspaper that is relevant to the date and the location of the poet. If you want to get even more specific, you can (for example, you could look at an abolitionist newspaper for Harper). If you can find one, you can also choose a newspaper where the writer published. • Select an issue of the newspaper and read the whole thing: news, editorials, poetry, even the advertisements. (Be forewarned, the print is tiny and there’s a lot of text.) As you read, make note of anything at all—newspaper poems, news items, even weather—that you feel gives interesting context to the work the class will be discussing. -

Draft Dissertation

Dissention in the Ranks—Dissent Within U.S. Civil-Military Relations During the Truman Administration: A Historical Approach by David A. “DAM” Martin B.A. in History, May 1989, Virginia Military Institute M.A. in Military Studies—Land Warfare, June 2002, American Military University M.B.A., June 2014, Strayer University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Graduate School of Education and Human Development of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education January 19, 2018 Dissertation directed by Andrea J. Casey Associate Professor of Human and Organizational Learning The Graduate School of Education and Human Development of the George Washington University certifies that David A. “DAM” Martin has passed the final examination for the degree of Doctor of Education as of September 22, 2017. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Dissention in the Ranks—Dissent Within U.S. Civil-Military Relations During the Truman Administration: A Historical Approach David A. “DAM” Martin Dissertation Research Committee: Andrea J. Casey, Associate Professor of Human and Organizational Learning, Dissertation Director David R. Schwandt, Professor Emeritus of Human and Organizational Learning, Committee Member Stamatina McGrath, Adjunct Instructor, Department of History, George Mason University, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2018 by David A. Martin All rights reserved iii Dedication Dedicated to those who have Served honorably, Dissented when the cause was just, and paid dearly for it. iv Acknowledgments I want to thank my dissertation chair, Dr. Andrea Casey, for her outstanding advice and counsel throughout this educative journey. Thank you to my dissertation committee member, Dr. -

Westhoff Book for CD.Pdf (2.743Mb)

Urban Life and Urban Landscape Zane L. Miller, Series Editor Westhoff 3.indb 1 5/14/2007 12:39:31 PM Westhoff 3.indb 2 5/14/2007 12:39:31 PM A Fatal Drifting Apart Democratic Social Knowledge and Chicago Reform Laura M. Westhoff The Ohio State University Press Columbus Westhoff 3.indb 3 5/14/2007 12:39:33 PM Copyright © 2007 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Westhoff, Laura M. A fatal drifting apart : democratic social knowledge and Chicago reform / Laura M. Westhoff. — 1st. ed. p. cm. — (Urban life and urban landscape) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1058-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1058-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9137-5 (cd-rom) ISBN-10: 0-8142-9137-6 (cd-rom) 1. Social reformers—Chicago—Illinois—History. 2. Social ethics—Chicago— Illinois—History. 3. Chicago (Ill.)—Social conditions. 4. United States—Social conditions—1865–1918. I. Title. HN80.C5W47 2007 303.48'40977311—dc22 2006100374 Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Type set in Minion Printed by Thomson-Shore The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Westhoff 3.indb 4 5/14/2007 12:39:33 PM To Darel, Henry, and Jacob Westhoff 3.indb 5 5/14/2007 12:39:33 PM Westhoff 3.indb 6 5/14/2007 12:39:33 PM Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xiii Introduction 1 Chapter 1. -

262671234.Pdf

Out of Sight Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff University Press of Mississippi / Jackson OutOut ofofOut of Sight Sight Sight The Rise of African American Popular Music – American Made Music Series Advisory Board David Evans, General Editor Barry Jean Ancelet Edward A. Berlin Joyce J. Bolden Rob Bowman Susan C. Cook Curtis Ellison William Ferris Michael Harris John Edward Hasse Kip Lornell Frank McArthur W. K. McNeil Bill Malone Eddie S. Meadows Manuel H. Peña David Sanjek Wayne D. Shirley Robert Walser Charles Wolfe www.upress.state.ms.us Copyright © 2002 by University Press of Mississippi All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 4 3 2 ϱ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Abbott, Lynn, 1946– Out of Sight: the rise of African American popular music, 1889–1895 / Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff. p. cm. — (American made music series) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 1-57806-499-6 (cloth: alk. paper) 1. African Americans—Music—Hisory and criticism. 2. Popular music—United States—To 1901—History and criticism. I. Seroff, Doug. II. Title. III. Series ML3479 .A2 2003 781.64Ј089Ј96073—dc21 2002007819 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available Contents Acknowledgments ϳ Introduction ϳ Chapter 1. 1889 • Frederick J. Loudin’s Fisk Jubilee Singers and Their Australasian Auditors, 1886–1889 ϳ 3 • “Same”—The Maori and the Fisk Jubilee Singers ϳ 12 • Australasian Music Appreciation ϳ 13 • Minstrelsy and Loudin’s Fisk Jubilee Singers ϳ 19 • The Slippery Slope of Variety and Comedy ϳ 21 • Mean Judge Williams ϳ 24 • A “Black Patti” for the Ages: The Tennessee Jubilee Singers and Matilda Sissieretta Jones, 1889–1891 ϳ 27 • Other “Colored Pattis” and “Queens of Song,” 1889 ϳ 40 • Other Jubilee Singers, 1889 ϳ 42 • Rev.