Practicing for Space Underwater: Inventing Neutral Buoyancy Training

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breathing & Buoyancy Control: Stop, Breathe, Think, And

Breathing & Buoyancy control: Stop, Breathe, Think, and then Act For an introduction to this five part series see: House of Cards 'As a child I was fascinated by the way marine creatures just held their position in the water and the one creature that captivated my curiosity and inspired my direction more than any is the Nautilus. Hanging motionless in any depth of water and the inspiration for the design of the submarine with multiple air chambers within its shell to hold perfect buoyancy it is truly a grand master of the art of buoyancy. Buoyancy really is the ultimate Foundation skill in the repertoire of a diver, whether they are a beginner or an explorer. It is the base on which all other skills are laid. With good buoyancy a problem does not become an emergency it remains a problem to be solved calmly under control. The secret to mastery of buoyancy is control of breathing, which also gives many additional advantages to the skill set of a safe diver. Calming one's breathing can dissipate stress, give a sense of well being and control. Once the breathing is calmed, the heart rate will calm too and any situation can be thought through, processed and solved. Always ‘Stop, Breathe, Think and then Act.' Breath control is used in martial arts as a control of the flow of energy, in prenatal training and in child birth. At a simpler more every day level, just pausing to take several slow deep breaths can resolve physical or psychological stress in many scenarios found in daily life. -

Man High Commemoration

NewsHopperTM Man High 50th Anniversary August 11, 2007 13 th 50Anniversary Man High Commemoration Please thank the advertisers for making this section possible. And a special thank you to Beverly Mindrum Johnson and the Cuyuna Country Heritage Preservation Society. Man High Schedule of Events Saturday, August 18, 2007 Sunday, August 19, 2007 9 a.m.— “Defeating Pain” symposium at The Hallett Community Center. 10 a.m.—Gathering and ceremonies at the Croft Mine Park open Session 1—Dr. Simons will speak on Trigger Point Therapy. to the public and providing an opportunity for area resi- 10:30 a.m.—Session 1—Carolyn McMakin will speak on Microcurrent Therapy. dents and other to meet the Man High participants. Noon—CATERED LUNCH provided by the Cuyuna Regional Medical Center. The Sunday schedule will include transporting guests to the Ports- Post-session informal discussion. mouth Overlook for a short ceremony. At that ceremony the Depart- 1:30 p.m.—Caravan to space presentation at the C-I High School Auditorium. ment of Natural Resources Man High II Kiosk will be unveiled. Band 2 p.m.—Dr. Simons, former Apollo Astronaut Duane Graveline and Dr. Mar- will perform military numbers. cello Vasquez, NASA liaison scientist with the Medical Department 10:45 a.m.— Return to Croft Mine Park for the Man High Ceremony. of Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, New York, will present a Colors will be presented by the Crosby and Ironton Legion Posts; three-part symposium on cosmic radiation and other hazards to hu- Carla Gutzman & Kris Hasskamp, solists; speakers will include Dr. -

In Memory of Astronaut Michael Collins Photo Credit

Gemini & Apollo Astronaut, BGEN, USAF, Ret, Test Pilot, and Author Dies at 90 The Astronaut Scholarship Foundation (ASF) is saddened to report the loss of space man Michael Collins BGEN, USAF, Ret., and NASA astronaut who has passed away on April 28, 2021 at the age of 90; he was predeceased by his wife of 56 years, Pat and his son Michael and is survived by their daughters Kate and Ann and many grandchildren. Collins is best known for being one of the crew of Apollo 11, the first manned mission to land humans on the moon. Michael Collins was born in Rome, Italy on October 31, 1930. In 1952 he graduated from West Point (same class as future fellow astronaut, Ed White) with a Bachelor of Science Degree. He joined the U.S. Air Force and was assigned to the 21st Fighter-Bomber Wing at George AFB in California. He subsequently moved to Europe when they relocated to Chaumont-Semoutiers AFB in France. Once during a test flight, he was forced to eject from an F-86 after a fire started behind the cockpit; he was safely rescued and returned to Chaumont. He was accepted into the USAF Experimental Flight Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California. In 1960 he became a member of Class 60C which included future astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Irwin, and Tom Stafford. His inspiration to become an astronaut was the Mercury Atlas 6 flight of John Glenn and with this inspiration, he applied to NASA. In 1963 he was selected in the third group of NASA astronauts. -

Hearing Transcript

The President’s Commission on Implementation of United States Space Exploration Policy PUBLIC HEARING Georgia Centers for Advanced Telecommunications Technology 250 14th Street, NW Atlanta, GA Wednesday, March 24, and Thursday, March 25, 2004 Pete Aldridge Well, good afternoon. I’m Pete Aldridge, I’m the Chairman of the President’s Commission on the Implementation of the U.S. Space Exploration Policy, or as I have shortened it, the “President’s Commission on the Moon, Mars, and Beyond.” I was delighted when I learned that Monica Scarbrough, the Director of Development, invited us here. The Georgia Institute of Technology is in fact my alma mater, and it’s generally great to be back on campus. I’m looking forward to looking around at some of the old haunts that I spent many hours on. The Commission is here to explore ways to achieve the President’s vision of going back to the Moon and on to Mars and beyond. We have listened, we’ve talked to experts at two previous hearings—in Washington, D.C., and in Dayton, Ohio. We’ve talked among ourselves and we realized this vision provides a focus not just for NASA, but a focus that can revitalize U.S. space capability and have a significant impact upon our nation’s industrial base and academia. As you can see from our agenda, we are talking with experts from many, many disciplines, including those outside the traditional aerospace arena. Before I go any further, let me introduce my fellow Commissioners. And begin on the audience’s right, Carly Fiorina. -

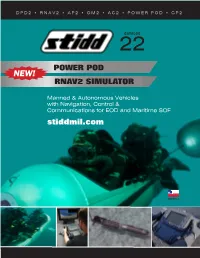

Stiddmil.Com POWER POD RNAV2 SIMULATOR

DPD2 • RNAV2 • AP2 • OM2 • AC2 • POWER POD • CP2 CATALOG 22 POWER POD NEW! RNAV2 SIMULATOR Manned & Autonomous Vehicles with Navigation, Control & Communications for EOD and Maritime SOF stiddmil.com MADE IN U.S.A. Manned or Autonomous... The “All-In-One” Vehicle Moving easily between manned and autonomous roles, STIDD’s new generation of propulsion vehicles provide operators innovative options for an increasingly complex underwater environment. Over the past 20 years, STIDD built its Submersible line and flagship product, the Diver Propulsion Device (DPD), around the basic idea that divers would prefer riding a vehicle instead of swimming. Today, STIDD focuses on another simple, but transformative goal: design, develop, and integrate the most advanced Precision Navigation, Control, Communications, and Automation Technology available into the DPD to make that ride easier, more effective, and when desired . RIDERLESS! DPD2 - Manned Mode 1 DPD2 - OM2 Mode Precision Navigation, Control, Communications & Automation System for the DPD POWERED BY RNAV2 GREENSEA Building on the legacy of its Diver Propulsion Device (DPD), the most widely used combat vehicle of its kind, STIDD designed and developed a system of DPD Navigation, Control, Communications, and Automation features which enable a seamless transition between Manned and fully Autonomous modes. RNAV2 was developed by STIDD partnering with Greensea as the backbone of this capability. RNAV2 is powered by Greensea’s patent-pending OPENSEA™ operating platform, which not only enables RNAV2’s open architecture, but also seamlessly integrates STIDD’s OM2/AP2 Diver Assist /S2 Sonar/ AC2 Communications products into an intuitive, easy to use, autonomous system. When fully configured with the Precision Navigation, Control & Automation System including RNAV2/ OM2/AP2/S2/AC2, any DPD easily transitions between Manned, DPD with RNAV2 Installed Semi-Autonomous, and Full-Autonomous modes. -

Balloon Astronaut San Jose, CA 95113 1-408-294-8324 Design Challenge Learning Thetech.Org

201 S. Market St. Balloon Astronaut San Jose, CA 95113 1-408-294-8324 Design Challenge Learning thetech.org Students investigate properties of materials and colliding objects by designing spacesuits for balloon astronauts. The objective is to design spacesuits that can withstand the hazards of high velocity impacts from space debris and meteoroids. As students iterate through this design challenge, they gain firsthand experience in the design process. Balloon Astronaut1 Grades 2-8 Estimated time: 45 minutes Student Outcomes: 1. Students will be able to design and build a protective device to keep their balloon astronaut from popping when impaled by a falling nail. 2. Students will be able to explain design considerations based on material characteristics, and concepts of energy, velocity, and the physics of colliding objects. 3. Students will be able to utilize the three step design process to meet an engineering challenge. Next Generation Science Standards Grade 2-5: Engineering Design K-2-ETS1-1, K-2-ETS1-2, K-2-ETS1-3, 3-5-ETS1-1, 3-5-ETS1-2, 3-5-ETS1-3 Grade 2: Physical Science 2-PS1-1, 2-PS1-2 Grade 3: Physical Science 3-PS2-1 Grade 4: Physical Science 4-PS3-1, 4-PS3-3, 4-PS3-4 Grade 5: Physical Science 5-PS2-1 Grade 6-8: Engineering Design MS-ETS1-1, MS-ETS1-2, MS-ETS1-3, MS-ETS1-4; Physical Science MS-PS2-1, MS-PS2-2, MS-PS3-2, MS-PS3-5 Common Core Language Arts-Speaking and Listening Grade 2: SL.2.1a-c, SL.2.3, SL.2.4a Grade 3: SL.3.1b-d, SL.3.3, SL.3.4a Grade 4: SL.4.1b-d, SL.4.4a Grade 5: SL.5.1b-d, SL.5.4 Grade 6: SL.6.1b-d Grade 7: SL.7.1b-d Grade 8: SL.8.1b-d California Science Content Grade 2: Physical Science 1.a-c; Investigation and Experimentation 4.a, 4.c-d Grade 3: Investigation and Experimentation 5.a-b, d Grade 4: Investigation and Experimentation 6.a, 6.c-d Grade 5: Investigation and Experimentation 6.a-c, 6.h Grade 6: Investigation and Experimentation 7.a-b, 7.d-e Grade 7: Investigation and Experimentation 7.a, 7.c-e Grade 8: Physical Science 1.a-e, 2.a-g; Investigation and Experimentation 9.b-c 1 Developed from a program designed by NASA. -

Law of Hydrostatics‘’)

10 LAW OF HYDROSTATICS‘’) 10.1 INTRODUCTION When a fluid is at rest, there is no shear stress and the pressure at any point in the fluid is the same in all directions. The pressure is also the same across any longitudinal section parallel with the Earth’s surface; it varies only in the vertical direction, that is, from height to height. This phenomenon gives rise to hydrostatics, the subject title for this chapter. Following this introduction, this chapter addresses (once again) pressure principles, buoyancy effects (including Archimedes’ Law), and manometry principles. 10.2 PRESSURE PRINCIPLES Consider a differential element of fluid of height, dz, and uniform cross-section area, S. The pressure, P, is assumed to increase with height, z. The pressure at the bottom surface of the differential fluid element is P; at the top surface, it is P + dP. Thus, the net pressure difference, dP, on the element is acting downward. A force balance on this element in the vertical direction yields: downward pressure force - upward pressure force + gravity force = 0 (10.1) Fluid Flow for the Pmcticing Chemical Engineer. By J. Pahick Abulencia and Louis Theodore Copyright 0 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 97 98 LAW OF HYDROSTATICS so that g (P + dP)S - PS + PS-dz = 0 gc g -(dP)S - p-S(dz) = 0 (1 0.2) gc As describe’ in Chapter 2, one has a choice as to whether to inc.Jde g, in the describ- ing equation(s). As noted, the term g, is a conversion constant with a given magnitude and units, e.g., 32.2 (lb/lbf)(ft/s2) or dimensionless with a value of unity, for example, g, = 1.0. -

Space Sector Brochure

SPACE SPACE REVOLUTIONIZING THE WAY TO SPACE SPACECRAFT TECHNOLOGIES PROPULSION Moog provides components and subsystems for cold gas, chemical, and electric Moog is a proven leader in components, subsystems, and systems propulsion and designs, develops, and manufactures complete chemical propulsion for spacecraft of all sizes, from smallsats to GEO spacecraft. systems, including tanks, to accelerate the spacecraft for orbit-insertion, station Moog has been successfully providing spacecraft controls, in- keeping, or attitude control. Moog makes thrusters from <1N to 500N to support the space propulsion, and major subsystems for science, military, propulsion requirements for small to large spacecraft. and commercial operations for more than 60 years. AVIONICS Moog is a proven provider of high performance and reliable space-rated avionics hardware and software for command and data handling, power distribution, payload processing, memory, GPS receivers, motor controllers, and onboard computing. POWER SYSTEMS Moog leverages its proven spacecraft avionics and high-power control systems to supply hardware for telemetry, as well as solar array and battery power management and switching. Applications include bus line power to valves, motors, torque rods, and other end effectors. Moog has developed products for Power Management and Distribution (PMAD) Systems, such as high power DC converters, switching, and power stabilization. MECHANISMS Moog has produced spacecraft motion control products for more than 50 years, dating back to the historic Apollo and Pioneer programs. Today, we offer rotary, linear, and specialized mechanisms for spacecraft motion control needs. Moog is a world-class manufacturer of solar array drives, propulsion positioning gimbals, electric propulsion gimbals, antenna positioner mechanisms, docking and release mechanisms, and specialty payload positioners. -

Appendix a Apollo 15: “The Problem We Brought Back from the Moon”

Appendix A Apollo 15: “The Problem We Brought Back From the Moon” Postal Covers Carried on Apollo 151 Among the best known collectables from the Apollo Era are the covers flown onboard the Apollo 15 mission in 1971, mainly because of what the mission’s Lunar Module Pilot, Jim Irwin, called “the problem we brought back from the Moon.” [1] The crew of Apollo 15 carried out one of the most complete scientific explorations of the Moon and accomplished several firsts, including the first lunar roving vehicle that was operated on the Moon to extend the range of exploration. Some 81 kilograms (180 pounds) of lunar surface samples were returned for anal- ysis, and a battery of very productive lunar surface and orbital experiments were conducted, including the first EVA in deep space. [2] Yet the Apollo 15 crew are best remembered for carrying envelopes to the Moon, and the mission is remem- bered for the “great postal caper.” [3] As noted in Chapter 7, Apollo 15 was not the first mission to carry covers. Dozens were carried on each flight from Apollo 11 onwards (see Table 1 for the complete list) and, as Apollo 15 Commander Dave Scott recalled in his book, the whole business had probably been building since Mercury, through Gemini and into Apollo. [4] People had a fascination with objects that had been carried into space, and that became more and more popular – and valuable – as the programs progressed. Right from the start of the Mercury program, each astronaut had been allowed to carry a certain number of personal items onboard, with NASA’s permission, in 1 A first version of this material was issued as Apollo 15 Cover Scandal in Orbit No. -

Complex Garment Systems to Survive in Outer Space

Volume 7, Issue 2, Fall 2011 Complex Garment Systems to Survive in Outer Space Debi Prasad Gon, Assistant Professor, Textile Technology, Panipat Institute of Engineering & Technology, Pattikalyana, Samalkha, Panipat, Haryana, INDIA [email protected] Palash Paul, Assistant Professor, Textile Technology, Panipat Institute of Engineering & Technology, Pattikalyana, Samalkha, Panipat, Haryana, INDIA ABSTRACT The success of astronauts in performing Extra-Vehicular Activity (EVA) is highly dependent on the performance of the spacesuit they are wearing. Since the beginning of the Space Shuttle Program, one basic suit design has been evolving. The Space Shuttle Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) is a waist entry suit consisting of a hard upper torso (HUT) and soft fabric mobility joints. The EMU was designed specifically for zero gravity operations. With a new emphasis on planetary exploration, a new EVA spacesuit design is required. Now the research scientists are working hard and striving for the new, lightweight and modular designs. Thus they have reached to the Red surface of Mars. And sooner or later the astronauts will reach the other planets too. This paper is a review of various types of spacesuits and the different fabrics required for the manufacturing of the same. The detailed construction of EMU and space suit for Mars is discussed here, along with certain concepts of Biosuit- Mechanical Counter pressure Suit. Keywords: Extra-Vehicular Activity (EVA), spacesuits, Biosuit-Mechanical Counter pressure Suit Tissues (skin, heart, -

2018 Annual Report San Diego Air & Space Museum Connections Mission Statement

2018 ANNUAL REPORT SAN DIEGO AIR & SPACE MUSEUM CONNECTIONS MISSION STATEMENT VISION VALUES The San Diego Air & Space Museum, one of the world’s The San Diego Air & Space Museum adheres to impeccable premier air and space-themed science center and professional standards as it preserves, interprets, educates museum, inspires our next greatest generations to achieve and shares its rich aviation and space resources: excellence in their lives by challenging their innate human • To act as exceptional stewards on behalf of the general pioneering spirit and encouraging the necessary risk- public and earn the trust of our donors and members taking required to achieve global innovation success. by caring for our collections. Interpret our collections MISSION accurately and use society’s generosity in a beneficial PRESERVE…INSPIRE…EDUCATION…CELEBRATE! manner conducive to the spirit of excellence on behalf of the common good for all. PRESERVE significant artifacts of air and space history and technology. • To inspire an interest in science, technology, engineering, mathematics (STEM) and innovation, as well as history. INSPIRE excellence in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Inspire the necessary risk-taking in future generations to ensure continued exploration of the outer bounds of EDUCATE the public about the historical and social what can be. significance of air and space technology and its future promise as a pathway to advanced innovations. • To educate through public outreach and engagement. CELEBRATE aviation and space flight history and • To honor the legacy of aviation and space flight technology. technology and the men and women who forged the path for others to emulate. -

Modeling Space Suit Mobility: Applications to Design and Operations

2001-01-2162 Modeling Space Suit Mobility: Applications to Design and Operations P. B. Schmidt and D. J. Newman Massachusetts Institute of Technology E. Hodgson Hamilton Sundstrand Space Systems International Copyright © 2001 Society of Automotive Engineers, Inc. ABSTRACT date repetitive tasks. Computer simulation also aids in future space suit design by allowing new space suit or Computer simulation of extravehicular activity (EVA) is component designs to be evaluated without the expense increasingly being used in planning and training for EVA. of constructing and certifying prototypes for human test- A space suit model is an important, but often overlooked, ing. While dynamic simulation is not currently used for component of an EVA simulation. Because of the inher- EVA planning, it has been used for post-flight analyses ent difficulties in collecting angle and torque data for [1, 2]. Other computer-based modeling and analysis space suit joints in realistic conditions, little data exists on techniques are used in pre-flight evaluations of EVA tasks the torques that a space suit’s wearer must provide in and worksites [3, 4]. order to move in the space suit. A joint angle and torque database was compiled on the Extravehicular Maneuver- An important shortcoming of current EVA models is that ing Unit (EMU), with a novel measurement technique that they lack an accurate representation of the torques that used both human test subjects and an instrumented are required to bend the joints of the space suit. The robot. Using data collected in the experiment, a hystere- shuttle EMU, like all pressurized space suits, restricts sis modeling technique was used to predict EMU joint joint motion to specific axes and ranges and has a ten- torques from joint angular positions.