Tree Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Buffer Handbook Plant List

THE BUFFER HANDBOOK PLANT LIST Originally Developed by: Cynthia Kuhns, Lake & Watershed Resource Management Associates With funding provided by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Maine Department of Environmental Protection,1998. Revised 2001 and 2009. Publication #DEPLW0094-B2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements 1 Introductory Information Selection of Plants for This List 1 Plant List Organization & Information 3 Terms & Abbreviations 4 Plant Hardiness Zone Map 5 General Tree & Shrub Planting Guidelines 5 Tips for Planting Perennials 7 Invasive Plants to Avoid 7 Plant Lists TREES 8 (30 to 100 ft.) SHRUBS 14 Small Trees/Large Shrubs 15 (12 to 30 ft.) Medium Shrubs 19 (6 to 12 ft.) Small Shrubs 24 (Less than 6 ft.) GROUNDLAYERS 29 Perennial Herbs & Flowers 30 Ferns 45 Grasses 45 Vines 45 References 49 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Original Publication: This plant list was published with the help of Clean Water Act, Section 319 funds, under a grant awarded to the Androscoggin Valley Soil and Water Conservation District and with help from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Graphics and ‘clip-art’ used in this document came from the University of Wisconsin-Extension and from Microsoft Office 97(Small Business Edition) and ClickArt 97 (Broderbund Software, Inc). This publication was originally developed by Cynthia Kuhns of Lake & Watershed Resource Management Associates. Substantial assistance was received from Phoebe Hardesty of the Androscoggin Valley Soil and Water Conservation District. Valuable review and advice was given by Karen Hahnel and Kathy Hoppe of the Maine Department of Environmental Protection. Elizabeth T. Muir provided free and cheerful editing and botanical advice. -

Tree Planting and Management

COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION Tree Planting and Management Breadth of Opportunity The spread of the Commission's responsibilities over some 148 countries in temperate, mediterranean, tropical and desert climates provides wonderful opportunities to experiment with nature's wealth of tree species. We are particularly fortunate in being able to grow many interesting and beautiful trees and we will explain how we manage them and what splendid specimens they can make. Why Plant Trees? Trees are planted for a variety of reasons: their amenity value, leaf shape and size, flowers, fruit, habit, form, bark, landscape value, shelter or screening, backcloth planting, shade, noise and pollution reduction, soil stabilisation and to encourage wild life. Often we plant trees solely for their amenity value. That is, the beauty of the tree itself. This can be from the leaves such as those in Robinia pseudoacacia 'Frisia', the flowers in the tropical tree Tabebuia or Albizia, the crimson stems of the sealing wax palm (Cyrtostachys renda), or the fruit as in Magnolia grandiflora. above: Sealing wax palms at Taiping War Cemetery, Malaysia with insert of the fruit of Magnolia grandiflora Selection Generally speaking the form of the left: The tropical tree Tabebuia tree is very often a major contributing factor and this, together with a sound knowledge of below: Flowers of the tropical the situation in which the tree is to tree Albizia julibrissin be grown, guides the decision to the best choice of species. Exposure is a major limitation to the free choice of species in northern Europe especially and trees such as Sorbus, Betula, Tilia, Fraxinus, Crataegus and fastigiate yews play an important role in any landscape design where the elements are seriously against a wider selection. -

Taxonomic Studies on the Lithocolletinae of Japan (Lepidoptera : Gracillariidae) Part 2

Title Taxonomic studies on the Lithocolletinae of Japan (Lepidoptera : Gracillariidae) Part 2 Author(s) Kumata, Tosio Citation Insecta matsumurana, 26(1), 1-48 Issue Date 1963-08 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/9698 Type bulletin (article) File Information 26(1)_p1-48.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP TAXONOMIC STUDIES ON THE LITHOCOLLETINAE OF JAPAN (LEPIDOPTERA : GRACILLARIIDAE) Part Ill) By TOSIO KUMATA Entomological Institute, Faculty of Agriculture Hokkaido University, Sapporo In this part there are given twenty-nine species attacking Ulmaceae, Rosaceae, Legumi nosae, Aceraceae, Ericaceae and Caprifoliaceae, and two host-unknown species of the Lithocolletinae_ Moreover, two new genera are erected for the reception of four new species attacking Leguminosae_ 7_ Species attacking Ulmaceae 32. Lithocolletis tritorrhecta Meyrick (Fig. 1; 3, I-K) Lithocolletis tritorrhecta Meyrick, 1935, Exot. Microlep. 4 : 596; Issiki, 1950, Icon. Ins. Jap.: 454, f. 1224. Phyllonorycter tritorrhecta: Inoue, 1954, Check list Lep. Jap. 1 : 28. This species is represented by the aestival and autumnal forms, which are different III colour. Aestival form: 0 ((. Face silvery-white; palpus whitish, with a blackish streak on pos terior surface; tuft of head golden-ochreous, mixed with many whitish scales in centre; antenna white, each segment ringed with dark brown apically. Thorax golden-ochreous, with two white, wide lines running along inner margins of tegulae, and with a white, small spot at posterior angle. Legs whitish; fore tibia clouded inside; mid tibia with three oblique black streaks outside; all tarsi with black blotches or spots at base, basal 1/3, 3/5 and 4/5. -

18. SORBUS Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 477. 1753.1 花楸属 Hua Qiu Shu Lu Lingdi (陆玲娣 Lu Ling-Ti); Stephen A

Flora of China 9: 144–170. 2003. 18. SORBUS Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 477. 1753.1 花楸属 hua qiu shu Lu Lingdi (陆玲娣 Lu Ling-ti); Stephen A. Spongberg Aria (Persoon) Host; Micromeles Decaisne; Pleiosorbus Lihua Zhou & C. Y. Wu; Sorbus subgen. Aria Persoon. Trees or shrubs, usually deciduous. Winter buds usually rather large, ovoid, conical, or spindle-shaped, sometimes viscid; scales imbricate, several, glabrous or pubescent. Leaves alternate, membranous or herbaceous; stipules caducous, simple or pinnately com- pound, plicate or rarely convolute in bud; leaf blade usually serrate, sometimes nearly entire, venation craspedodromous or campto- dromous, glabrous or pubescent. Inflorescences compound, rarely simple corymbs or panicles. Hypanthium campanulate, rarely ob- conical or urceolate. Sepals 5, ovate or triangular, glabrous, pubescent, or tomentose, sometimes glandular along margin. Petals 5, glabrous or pubescent, base clawed or not. Stamens 15–25(–44) in 2 or 3 whorls, unequal in length; anthers ovoid or subglobose. Carpels 2–5, partly or wholly adnate to hypanthium; ovary semi-inferior to inferior, 2–5(–7)-loculed, with 2 or 3(or 4) ovules per locule, one usually abortive; styles 2–5, free or partially connate, glabrous or pubescent. Fruit a pome, white, yellow, pink, or brown to orange or red, ovoid or globose to ellipsoid or oblong, usually small, glabrous or pubescent, laevigate or with small lenticels, apically with sepals persistent or caducous leaving an annular scar, with 2–5(–7) locules, each with 1 or 2 exendospermous seeds; seeds several, with thin perisperm and endosperm enclosing embryo with compressed cotyledons. About 100 species: widely distributed throughout temperate regions of Asia, Europe, and North America; 67 species (43 endemic) in China. -

Magnolia Obovata

ISSUE 80 INAGNOLN INagnolla obovata Eric Hsu, Putnam Fellow, Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University Photographs by Philippe de 8 poelberch I first encountered Magnolia obovata in Bower at Sir Harold Hillier Gardens and Arboretum, Hampshire, England, where the tightly pursed, waxy, globular buds teased, but rewarded my patience. As each bud unfurled successively, it emitted an intoxicating ambrosial bouquet of melons, bananas, and grapes. Although the leaves were nowhere as luxuriously lustrous as M. grandrflora, they formed an el- egant wreath for the creamy white flower. I gingerly plucked one flower for doser observation, and placed one in my room. When I re- tumed from work later in the afternoon, the mom was overpowering- ly redolent of the magnolia's scent. The same olfactory pleasure was later experienced vicariously through the large Magnolia x wiesneri in the private garden of Nicholas Nickou in southern Connecticut. Several years earlier, I had traveled to Hokkaido Japan, after my high school graduation. Although Hokkaido experiences more severe win- ters than those in the southern parts of Japan, the forests there yield a remarkable diversity of fora, some of which are popular ornamen- tals. When one drives through the region, the silvery to blue-green leaf undersides of Magnolia obovata, shimmering in the breeze, seem to flag the eyes. In "Forest Flora of Japan" (sggII), Charles Sargent commended this species, which he encountered growing tluough the mountainous forests of Hokkaido. He called it "one of the largest and most beautiful of the deciduous-leaved species in size and [the seed conesj are sometimes eight inches long, and brilliant scarlet in color, stand out on branches, it is the most striking feature of the forests. -

TREES for WESTERN NEBRASKA Justin Evertson & Bob Henrickson

THE NEBRASKA STATEWIDE ARBORETUM PRESENTS TREES FOR WESTERN NEBRASKA Justin Evertson & Bob Henrickson. For more plant information, visit plantnebraska.org or retreenbraska.unl.edu The following species are recommended for areas in the western half of Nebraska and/or typically receive less than 20” of moisture per year. Size Range: The size range indicated for each plant is the expected average mature height x spread for Nebraska. Large Deciduous Trees (typically over 40 feet tall at maturity) 1. Ash, Black ‐ Fraxinus nigra (good on wet sites; very cold tolerant; Fallgold a common form; 45’x 35’) 2. Ash, Green ‐ Fraxinus pennsylvanica (native; very adaptable; good on wet or dry sites; over‐planted; 40‐60’x 25‐40’; 3. Ash, White ‐ Fraxinus americana (native eastern G.P.; good purple/yellow fall color; 40‐50’x 40‐50’) NOTE ON ASH SPECIES: Native American ash trees including those above are being decimated by Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) and the insect is now in Nebraska. NSA recommends that native ash species no longer be planted in Nebraska. 4. Ash, Manchurian ‐ Fraxinus mandshurica (from Asia; upright growth; drought tolerant; may be resistant to EAB; 40’x 30’) 5. Catalpa, Northern ‐ Catalpa speciosa (native; tough tree; large, heart‐shaped leaves, showy flowers and long seed pods; 50’x 35’) 6. Coffeetree, Kentucky ‐ Gymnocladus dioicus (native; amazingly adaptable; beautiful winter form; 50’x 40’) 7. Cottonwood, Eastern ‐ Populus deltoides (majestic native; not for extremely dry sites; avoid most cultivars; 80’x 60’) 8. Cottonwood, Lanceleaf ‐ Populus acuminata (native; naturally occurring hybrid; narrow leaves; for west. G.P.; 50’x 35’) 9. -

The Propagation of M. Amoena Cheng: a Rare Chinese Endemic by Rob Nicholaon of a Large Number of Species

The propagation of M. amoena Cheng: A rare Chinese endemic by Rob Nicholaon of a large number of species. It is a complex mix of plants with no In the autumn of 1982 the species or group of species taxonomists the Arnold of dominating the forest composition Arboretum were excited to see, in and it shows a high number of the Index Seminum the Hangzhou of endemics and monotypic plants. Botanic Garden, a listing of the rare T. P. Chang enumerated the vascular and untested magnolia species, flora of the Tienmu Mountains in Magnolia amoena. We eagerly 1936 and counted a mind-boggling requested seed and late February by 424 woody species. arrived and of the following year it Of the 180 that are trees, 67 wss immediately cold stratified. species form the canopy layer. Subsequent sowing three months Magnolia amoena is found in this later produced 12 seedlings which, to uppermost strata of the forest at an of due the dismay all, died to altitude of 700 to 1000 meters. This damping off. zone is dominated by broad-leaved Attempts to secure more seed from deciduous species, although a number Hangzhou were unsuccessful, and in of conifers do appear. A list of the back of mind have always my I Magnolia amoena's companion wished to atone for this disaster, species might give us some even to go to China and collect seed indication of the plant's unknown myself. A proposal was put forth to hardiness although this be a the Chinese Academy of Sciences may fool's best. -

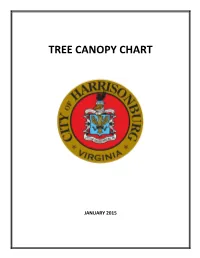

Tree Canopy Chart

TREE CANOPY CHART JANUARY 2015 Tree Canopy Coverage after 10 Years Based on information from Virginia Nursery & Landscape Association, Inc., and "tree Canopy Spread and coverage in Urban Landscapes database dated 11/3/2010. http://dendro.cnre.vt.edu/predictions/canopy.cfm Planting Size Caliper - in Tree Canopy Coverage Latin Name Common Name(s) Height - in feet inches After 10 Years© See Note 1 below. (square feet) DECIDUOUS TREES: Acer barbatum Florida Maple, Southern Sugar Maple 6-7 87 A. buergeranum Trident Maple 6-7 64 A. campestre Hedge Maple 6-7 64 A. ginnala Amur Maple 6-7 64 A. palmatum Japanese Maple 6-7 64 A. platanoides Norway maple 2-2 1/2 143 A. pseudoplatanus Sycamore maple 2-2 1/2 143 A. rubrum Red Maple 2-2 1/2 143 A. saccharum Sugar Maple, Rock Maple 2-2 1/2 143 A. truncatum 'Pacific Sunset' Pacific Sunset' Maple 177 A. x freemanii 'Autumn Blaze' Autumn Blaze' Maple 2-2 1/2 154 Aesculus flava Yellow Buckeye, Common Buckeye 6-7 64 A. glabra Ohio Buckeye, American Buckeye 6-7 64 A. hippocastanum Horse-Chestnut, Conker Tree 2-2 1/2 143 A. pavia Red Buckeye, Firecracker Plant 6-7 71 Alnus glutinosa Common Alder, Black Alder 2-2 1/2 95 Amelanchier arborea Downy Serviceberry, Common Serviceberry 6-7 95 A. laevis Smooth Shadbush, Allegheny Serviceberry 95 Amelanchier canadensis Canadian Serviceberry, Chuckleberry 2-5 33 Amelanchier x grandiflora 2-5 44 Betula maximowicziana Monarch Birch 2-2 1/2 95 B. nigra Black Bustard 2-2 1/2 165 B. -

The Reaction of Different Sorbus L. Species to Low Temperatures During Thaw in the Orel Region

Original Paper Journal of Forest Science, 65, 2019 (6): 218–225 https://doi.org/10.17221/8/2019-JFS The reaction of different Sorbus L. species to low temperatures during thaw in the Orel region Zoya Ozherelieva*, Olga Emelianova Russian Research Institute of Fruit Crop Breeding (VNIISPK), Orel, Russia Corresponding author: [email protected] *Citation: Ozherelieva Z., Emelianova O. (2019): The reaction of different Sorbus L. species to low temperatures during thaw in the Orel region. J. For. Sci., 65: 218–225. Abstract: Five Sorbus L. species of different ecological and geographical origin growing in the VNIISPK arboretum were studied. The Institute is located 368 km southwest of Moscow, on the Central Russian upland in the European part of Russia. The studies were carried out in 2014–2016. The reaction of different Sorbus L. species to a three-day thaw +2°C with a subsequent decrease in temperature to –25°C in February and –30°C in March was studied in or- der to identify adapted species to the climatic conditions of the Orel region for use in ornamental horticulture. As a result of the experiment, we recommend Sorbus aria (L.) Crantz, Sorbus aucuparia L. and Sorbus alnifolia (Siebold. et Zucc.) K. Koch. as adapted species for the Orel region to create sustainable landscape compositions. Keywords: artificial freezing; adaptation; frost hardiness Low temperature is a key environmental fac- es (Groffman et al. 2001; Schaberg et al. 2008; tor determining the evolution and distribution of Ozherelieva, Sedov 2017). Thus in nature, slight plants (Hawkins et al. 2014). Frost can damage freezing or death of trees is observed as a conse- plants through xylem embolism and the forma- quence of sharp temperature declines during thaws tion of extracellular ice, which causes cell dehydra- in February and March which cause trees to break tion and disruption of cell membranes (Zwiazek deep dormancy. -

Approved Boulevard Tree Planting List

City of Rochester Approved Boulevard Trees Below is a comprehensive list of all species currently approved by the City of Rochester for boulevard and Right of Way (ROW) tree planting. Property owners must obtain a Tree Planting Permit prior to planting. All trees desired by owner from the approved planting list may not be allowed due to tree diversity in the area, site conditions, or planting space restrictions. The planting permit will define the authorized trees and locations for planting. Follow the provided planting specifications to ensure that the tree planted lives a long life. Boulevard Tree Planting Specifications Trees must be a minimum of 1.5’’ caliper. Clumps are not permitted in the ROW or boulevard, single stem only. To ensure that your tree is of hardy nursery stock, please purchase the tree from a local tree nursery. For information on how to plant your specific Trees MUST be planted at least: boulevard tree, please use this planting guide 10 feet from driveways from Purdue University as a reference: 12 feet from any above ground utilities https://www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/fn r/fnr-433-w.pdf 25 feet from intersections of sidewalks 25 feet from existing small stature boulevard trees 35 feet from existing large stature boulevard trees or future boulevard planting locations 20 feet from light poles and power poles Contact us for more information at: 507-328-2515 or [email protected] 1 City of Rochester Approved Boulevard Trees * Denotes Native to Minnesota SMALL- STATURE TREES Cherry, Amur Choke Prunus maackii Height: 20-30’ Width: 18-25’ Hardiness Zone: 2 to 6 Description: Dense and broadly rounded crown, yellow fall color, attractive, exfoliating golden to russet brown bark. -

Tracheophyte of Xiao Hinggan Ling in China: an Updated Checklist

Biodiversity Data Journal 7: e32306 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.7.e32306 Taxonomic Paper Tracheophyte of Xiao Hinggan Ling in China: an updated checklist Hongfeng Wang‡§, Xueyun Dong , Yi Liu|,¶, Keping Ma | ‡ School of Forestry, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China § School of Food Engineering Harbin University, Harbin, China | State Key Laboratory of Vegetation and Environmental Change, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China ¶ University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China Corresponding author: Hongfeng Wang ([email protected]) Academic editor: Daniele Cicuzza Received: 10 Dec 2018 | Accepted: 03 Mar 2019 | Published: 27 Mar 2019 Citation: Wang H, Dong X, Liu Y, Ma K (2019) Tracheophyte of Xiao Hinggan Ling in China: an updated checklist. Biodiversity Data Journal 7: e32306. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.7.e32306 Abstract Background This paper presents an updated list of tracheophytes of Xiao Hinggan Ling. The list includes 124 families, 503 genera and 1640 species (Containing subspecific units), of which 569 species (Containing subspecific units), 56 genera and 6 families represent first published records for Xiao Hinggan Ling. The aim of the present study is to document an updated checklist by reviewing the existing literature, browsing the website of National Specimen Information Infrastructure and additional data obtained in our research over the past ten years. This paper presents an updated list of tracheophytes of Xiao Hinggan Ling. The list includes 124 families, 503 genera and 1640 species (Containing subspecific units), of which 569 species (Containing subspecific units), 56 genera and 6 families represent first published records for Xiao Hinggan Ling. The aim of the present study is to document an updated checklist by reviewing the existing literature, browsing the website of National Specimen Information Infrastructure and additional data obtained in our research over the past ten years. -

University of Reading Guidance Note on Tree Planting

UNIVERSITY OF READING GUIDANCE NOTE ON TREE PLANTING 1.0 INTRODUCTION The University of Reading has many rare and historic trees and is conscious of its duty to ensure the continuing amenity and environmental value of the campus. This can only be achieved by the appropriate selection of species and planting to the highest standards. The Grounds Maintenance Section is well aware of the potential conflicts that trees can provoke, many of which can be avoided by giving careful consideration to the species selected and the sites that they are planted. This aims to give practical advice, guidance and references to all those involved with tree planting on University property, with the aim of: • Preventing damage to University property or services • Reducing the need for future maintenance • Reducing future hazards 2.0 SELECTION OF SPECIES This guide does not intend to discuss the amenity value of tree species, as there are already many books on the subject but does hope to highlight considerations that should be made to ensure the most suitable species are selected for the site. 2.1 TOXICITY There are a number of tree species that are toxic if ingested or their sap can cause contact allergic reactions to skin and eyes. The likelihood of serious poisoning occurring is extremely unlikely because trees are generally unpalatable and are unlikely to be eaten in large quantities. Site assessment should be carried out before known toxic species are chosen. Species Common Name Toxic Hazard Aesculus sp. Chestnut Ingested fruits Ilex sp. Holly Ingested fruits Laburnum sp. Golden Rain Ingested seeds Ligustrum lucidum Chinese Privet Ingested fruits Rhus sp.