The Report of the Mayor of Liverpool's Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transfer From

TRANSFER FROM PRIMARY TO SECONDARY SCHOOl Information for parents September 2022 email: [email protected] INTRODUCTION This information booklet is aimed at the parents of children currently in Year 5 who will become eligible from 12th September 2021 to make their secondary applications for Year 7 places starting in September 2022. This information booklet outlines what will happen and gives you guidance about how you can get more information about schools and advice about how to apply for school places. From 12th September you are then able to make your school preferences application at liverpool.gov.uk/admissions where there is further information and guidance posted online. CHOOSING A SCHOOL The Liverpool city council website includes the composite prospectus admissions information spread across its webpages at liverpool.gov.uk/admissions This includes important information about how to apply to schools; what criteria are used to allocate places if a school gets more applications than it has places available and how places were allocated in the previous year. Before expressing a preference for a school it is important that you understand the school’s admission policy and know whether or not the school was oversubscribed in the previous year. By using this information you can assess your child’s chances of gaining a place in the school. In addition to the composite prospectus admissions information online at liverpool.gov.uk/admissions there are several other sources of information that you can use to find out more about schools, these include the following: • School Open Evenings. (Please see Open Evening section within this booklet for further details) • School websites • School Admissions Team (Contact details can be found in the Contact Points section in this information booklet). -

Upper School

1 Editor’s Note Welcome to the first edition of Liverpool College’s Middle School Magazine College Column. Over the past few months, I have been working with both Year 8 Butler’s and Year 8 Brook’s during Thursday activity sessions to bring you this inaugural issue. Firstly, I would like to applaud the efforts of all pupils that were involved in the making of this very first version of College Column. I am extremely grateful for the hard work and dedication demonstrated by the pupils of both Butler’s and Brook’s during this process. Moreover, I would like to thank Mr Cartwright for arranging this activity and allowing pupils to become creative outside of the classroom. It has been a privilege to see pupils develop original ideas into complete articles. Additionally, I am very excited to begin working on future editions of College Column with the other Year 8 forms throughout the remainder of the academic year. If you’re in a Year 8 form, get thinking of future articles that you would like to include in your personal issue of College Column. Finally, to you the reader, thank you for taking the time to read the very first College Column. This version of College Column puts particular emphasis on Liverpool College’s recent (and quite frankly fantastic GCSE results) in addition to providing advice for our new Year 7 pupils, a range of original pieces of creative writing and information about the impending school play Bye, Bye Birdie. There are a range of puzzles and activities to complete in the magazine. -

Post 16 Provision Update for Local Offer

Preparing for Adulthood – Post 16 update for Local Offer The information below has been taken from the websites listed, which was written by the individual providers. This list does not reflect any endorsement by Halton Borough Council. It is merely a list of known providers to provide basic information about Post 16 Provision. Provision Contact Details Ashley School - Halton Mike Jones Head of 6th Form Maintained Special School Ashley High School Ashley High School 6th Form provides specialist Cawfield Avenue education for boys and girls, aged 16 to 19, with Widnes Asperger's Syndrome, higher-functioning autism and Cheshire social communication difficulties. The 6th form focus is WA8 7HG on continued core academic qualifications, a range of 0151 424 4892 vocational qualifications, preparation for adulthood and [email protected] career planning, whilst recognising the individual abilities and strengths of each student and enabling www.ashleyhighschool.co.uk them to reach their full potential. Bolton College – Greater Manchester Janet Bishop College of Further Education Head of Learner Support Bolton college provides high quality learning Bolton College opportunities and support throughout the curriculum, to Deane Road Bolton BL3 5BG learners with a wide range of disabilities and learning 01204 482654 difficulties including visual and hearing impairments, [email protected] mental health and emotional difficulties and autism. Learners can access a variety of vocational and www.boltoncollege.ac.uk/ prevocational courses -

Open PDF 715KB

LBP0018 Written evidence submitted by The Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium Education Select Committee Left behind white pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds Inquiry SUBMISSION FROM THE NORTHERN POWERHOUSE EDUCATION CONSORTIUM Introduction and summary of recommendations Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium are a group of organisations with focus on education and disadvantage campaigning in the North of England, including SHINE, Northern Powerhouse Partnership (NPP) and Tutor Trust. This is a joint submission to the inquiry, acting together as ‘The Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium’. We make the case that ethnicity is a major factor in the long term disadvantage gap, in particular white working class girls and boys. These issues are highly concentrated in left behind towns and the most deprived communities across the North of England. In the submission, we recommend strong actions for Government in particular: o New smart Opportunity Areas across the North of England. o An Emergency Pupil Premium distribution arrangement for 2020-21, including reform to better tackle long-term disadvantage. o A Catch-up Premium for the return to school. o Support to Northern Universities to provide additional temporary capacity for tutoring, including a key role for recent graduates and students to take part in accredited training. About the Organisations in our consortium SHINE (Support and Help IN Education) are a charity based in Leeds that help to raise the attainment of disadvantaged children across the Northern Powerhouse. Trustees include Lord Jim O’Neill, also a co-founder of SHINE, and Raksha Pattni. The Northern Powerhouse Partnership’s Education Committee works as part of the Northern Powerhouse Partnership (NPP) focusing on the Education and Skills agenda in the North of England. -

The Merseyside Science and Technology Challenge Days for Gifted and Talented Year 8 and Year 9S

The Merseyside Science and Technology Challenge Days for Gifted and Talented Year 8 and Year 9s What are the Science & Technology Days for? How are they rated? They raise enthusiasm for STEM subjects and encour- Evaluations of last year’s events indicated that…. age young people to consider studying them further. 99% of the teachers and 83% of the young people con- In 2015, MCS Projects Ltd organised 42 Challenge Days sidered their Day to have been ‘good’ or ‘very good’. across the UK, involving more than 300 schools. 73% of the young people were more likely to consider What happens? studying STEM subjects at college or university as a result of the event. Twelve Gifted and Talented Year 8/9s are invited to participate from each school. Working together in mixed school teams of four, they undertake practical activities that increase their awareness of the applica- tion of science. Each activity is designed to develop skills that will be needed in the workplace, with marks being awarded for planning, team work and the finished product. Challenge Days are usually held on the campus of a local college or university. The young people undertake three 75min activities. The local Mayor or Deputy Lieu- The overall winning teams from each Challenge Day tenant is invited to present awards to members of each progress to one of our regional Finals. In 2015, the winning team. Finals were hosted by the Universities of Cambridge, Manchester and Sheffield. Director: P.W.Waterworth 12 Edward Terrace, Sun Lane, Alresford, Hampshire SO24 9LY Registered in England: No 4960377 • VAT Reg. -

Feasibility Analysis for the Establishment of a Sixth Form College in Liverpool

University of Piraeus Department of Business Administration Title of Thesis: FEASIBILITY ANALYSIS FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A SIXTH FORM COLLEGE IN LIVERPOOL Master in Business Administration Executive MBA Melina Gousiou Student I.D. number: ΕΜΒΑ1308 November 2015 FEASIBILITY ANALYSIS FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A SIXTH FORM COLLEGE IN LIVERPOOL FEASIBILITY ANALYSIS FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A SIXTH FORM COLLEGE IN LIVERPOOL FEASIBILITY ANALYSIS FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A SIXTH FORM COLLEGE IN LIVERPOOL Acknowledgments I would never have been able to finish my dissertation without the guidance of my committee members, help from friends, and support from my family and husband. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Prof. Phillipas Nikolaos, for his excellent guidance, caring, patience, and providing me with an excellent atmosphere for writing my dissertation. I would like to thank Prof. Georgakellos Dimitrios, who let me work by him and gave me insight into financial issues thanks to his experience on practical issues beyond the textbooks and patiently corrected my writing. Special thanks goes to Prof. Papanastasopoulos Georgios, who was willing to participate in my final committee at the last moment. I would like to thank all the members of staff from Fazakerley High School, who as good friends, were always willing to help and give their best suggestions. It would have been a lonely research without them. Many thanks to Mr. James Beaton, Mr. Chris Scott, Miss T. Cunningham, Mrs. Sue Russell and other staff of the school for helping me collect all the data I needed to finish my dissertation. My research would not have been possible without their help. -

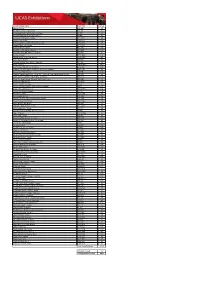

School/College Name Post Code Group 9629 9826

School/college name Post code Group Abacus College L15 4LE 10 All Saints Catholic High School L33 8XF 42 Archbishop Beck Catholic Sports College L9 7BF 125 Archbishop Blanch C of E High School L76HQ 80 Bebington High Sports College CH632PS 30 Benton Park School LS19 6LX 130 Birkenhead School, Birkenhead, Merseyside CH43 2JD 47 Bishop Heber High School SY14 8JD 125 Bolton VI Form College BL3 5BU 200 Broadgreen International School L13 5UQ 137 Broughton Hall High School, Liverpool L12 9HJ 85 Burnley College BB12 0AN 150 Calday Grange Grammar School CH48 8GG 228 Calderstones School L183HS 117 Cardinal Heenan High School, Liverpool L12 9HZ 65 Carmel College WA10 3AG 779 Castell Alun High School, Wrexham LL12 9HA 106 Cheslyn Hay Sport and Community High School, Walsall WS6 7JQ 93 Chesterfield High School L239YB 100 Childwall Sports and Science Academy - (formerly A Specialist Sports School) L15 6XZ 50 Christ the King Catholic High School, Southport PR8 4EX 100 Christ The King Catholic School & Sixth Form Centre PR8 4EX 90 Christleton High School CH3 7AD 190 City of Liverpool College L77JA 11 City of Liverpool College, The Learning Exchange L35TP 111 Cowley International College WA10 6PN 130 Deyes High School, Maghull L31 6DE 150 Ellesmere College SY12 9AB 80 Formby High School L37 3HW 150 Gateacre Community Comprehensive School L25 2RW 50 Great Sankey High School WA5 3AA 120 Grove School, Shropshire TF9 1HF 75 Hawarden High School, Deeside CH5 3DN 88 Holly Lodge Girls College L12 7LE 40 Holy Family Catholic High School, Liverpool L234UL 53 -

Cronton Sixth Form College, a Centre of Academic Excellence

2020 SE GUIDE OUR C www.cronton.ac.uk CRONTON SIXTH FORM COURSE GUIDE 2020 Open Events • Wednesday 9th October 5.30pm – 7.30pm • Thursday 10th October 5.30pm – 7.30pm • Thursday 7th November 5.30pm – 7.30pm • Thursday 27th February 5.30pm – 7.30pm Hannah Bloor & Shakira Raynes Both previously from • 99.5% A Level Pass Rate 2019 Wade Deacon High School and now studying • 100% Vocational Pass Rate 2019 Law at university. • 64% Top Grades A* - B (or equivalent) • 81% High Grades A*- C (or equivalent) 02 Contents Centre of Excellence in Science, COURSE GUIDE 2020 Welcome 4 42 Technology, Engineering and Maths (STEM) Travel to College 6 Reasons to Choose Cronton Sixth Form 7 School of English, Humanities A Level Results 8 52 and Modern Foreign Languages Vocational Results 9 Cronton Facilities 10 • IDEA Centre Centre of Excellence in Performing Arts 60 • NEW: Cronton Playhouse Student Success 14 SIXTH FORM CRONTON Investing in Teaching Excellence 18 School of Creative Arts and Media 66 Personal and Academic Support 19 THE CRONTON EXPERIENCE 21 School of Business 72 Outstanding Activities 22 Prestigious Universities Programme 24 Prestigious Studies Programmes 26 Centre of Sporting Excellence 74 Centres of Excellence 30 Scholarships 33 International College Trips 34 Health and Social Care and Nursing 78 COURSES 37 • A Levels 38 • Vocational Courses 40 Public Services 80 How to Apply 82 See page 38 & 40 for page numbers for individual courses. 03 CRONTON SIXTH FORM COURSE GUIDE 2020 Welcome Welcome to Cronton Sixth Form College, a Centre of Academic Excellence Ensuring that every student reaches their full potential is at the heart of everything we do at Cronton Sixth Form. -

School Prospectus 2021

Education for 16-19 year olds Prospectus 2021 Find out more liverpoolmathsschool.org E: [email protected] // 1 Contents Our mission 2 Headteacher’s Why choose our Maths School? 4 welcome Why Maths Schools? 10 Sixth Form life at the The University of Liverpool Maths School welcomed its first University of Liverpool students in September 2020 and is already an inspiring school Damian Haigh Maths School 14 in which to study and teach. Our staff feel privileged to work Headteacher Your study programme 18 with a student body made up of interesting, talented and highly I know how fortunate I am to be the headteacher of In this school they can be the teachers and carers They learn to think and talk in rigorous, mathematical Course information 20 committed young people. The students reciprocate by taking this very special school. It is a delight every day to they want to be – working hard with great students ways. They quickly start to enjoy this and to support see talented and hardworking students thriving and but not stressed and not distracted by poor behaviour. each other’s learning as part of the process. great pride in their school, by expressing gratitude for the never having to hide their enthusiasm for abstract Future professionals 22 We provide inspiration and expert support to provide An education at the University of Liverpool Maths understanding. As a maths teacher I have often excellent teaching and pastoral care and, above all, by the right kind of challenge and inspiration for our School is certainly challenging, but our students will thought that the brightest and most committed Entry requirements 25 students: to prepare them properly for places on also tell you that it’s deeply rewarding, huge fun and students get the worst deal in school, being put in working hard and learning rapidly. -

School Leavers' Prospectus 2020

REAL CAREERS START WITH REAL EXPERIENCES SCHOOL LEAVER PROSPECTUS 2020 FREE COLLEGE BUS ROUTE A SEFTON ST HELENS Main Campus IAMTech LIVERPOOL Campus KNOWSLEY ROUTE C VISIT WWW.KNOWSLEYCOLLEGE.AC.UK/FREEBUS FOR FULL ROUTES AND TIMINGS ROUTE A Maghull Melling Mount Kirkby Train Station Kirkby Town Centre Fazakerley Knowsley Community College Main Campus FREE COLLEGE BUS FREE COLLEGE Knowsley Community College IAMTech Campus ROUTE C Halewood Woolton Calderstones Park Queens Drive, Fiveways Alder Road Honey’s Green Lane Knowsley Community College Main Campus Knowsley Community College IAMTech Campus FREE BUS TRAVEL GETTING TO KNOWSLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE IS EASIER THAN EVER! We provide a free bus pass for the whole academic year, which can be used every weekday during term time. We also offer a free College bus across the following areas: NEW FOR 2019 NEW ROUTE COVERING FAZAKERLEY! MAGHULL KIRKBY FAZAKERLEY HALEWOOD WOOLTON WEST DERBY TURN OVER FOR MORE INFORMATION... /knowsleycollege www.knowsleycollege.ac.uk YOUR JOURNEY STARTS HERE Welcome to Knowsley Community College, a place to discover who you are and what you are capable of. We are dynamic, innovative and modern, having invested millions in our Main Campus and IAMTech Campus, to give you the ultimate student experience. We have produced thousands of successful students that have gone on to do spectacular things (you’ll find them inside this prospectus). So whatever your background, ambitions and interests, we have hundreds of courses to suit you and how you would like to learn. You could choose from A levels, Vocational/ BTEC courses or an Apprenticeship, all designed to help you achieve your dream career. -

The Wombats' Daniel Haggis

OBMAGAZINE 2020 INSIDE... PARLOPHONE RECORDS' NICK BURGESS SARAH CREED ART CURATOR OF ONE OF LONDON’S MOST TALKED ABOUT MUSEUMS Playwright, author and television scriptwriter JONATHAN HARVEY Blue Coat Eco-Committee drives NEW GREEN AGENDA CHESS CLUB’S THE WOMBATS' RESURGENCE DANIEL HAGGIS NICK COWAN ON PERFORMING WITH PUTTING THE BLAZE THE ROLLING STONES INTO BLAZER CONTENTS CONTENTS KEEP IN TOUCH! We require your consent to communicate with you. 12 To view our Privacy Notice and communications consent form head over to our website. Once complete you will never miss an event invitation, e-newsletter or Old Blues magazine. www.bluecoatschoolliverpool. 38 HITTING36 THE RIGHT org.uk/old-blues/keep-touch 4 16 NOTE You can contact the Development 4 SCHOOL NEWS 22 AND THE AWARD 39 TECH STARTUP ZYNG Team directly at development-team @bluecoatschool.org.uk or on 7 SPORT REPORT GOES TO… 40 CALL THE BLUE COAT 0151 733 1407 ext. 207 9 CATCHING UP WITH… 23 ROBERT SKYNER MIDWIFE Don’t forget you can also keep in touch THE CLASS OF 2019 RAISES THE BAR 41 FLYING DOCTOR MATT with Blue Coat using our social media platforms: 10 TAKING TO THE STAGE 24 WOMEN IN STEAM IS READY FOR TAKE 12 INTERVIEW WITH… 26 INTRODUCING NICK OFF - AGAIN! /bluecoatschoololdblues JONATHAN HARVEY BURGESS, CO-PRESIDENT 42 5 MINUTES WITH… 14 IN BRIEF... OF PARLOPHONE RICHARD DOWNEY @LiverpoolBCS 16 EMPOWERING ART 28 NICK COWAN, PUTTING 43 REDMEN OF LIVERPOOL 18 POPPING IN TO SAY THE BLAZE INTO BLAZER www.linkedin.com/ 44 OLD BLUES AROUND groups/8153535 HELLO 30 OLD BLUES INSPIRING THE WORLD 19 5 MINUTES WITH… THE NEXT GENERATION 46 BE MINDFUL ABOUT Cover photo: Old Blue Daniel Haggis, GRAHAM JONES 32 PASS IT ON YOUR MENTAL HEALTH from the Class of 2002, and his band The Wombats perform at the 2019 19 DELVE INTO THE ARCHIVE 36 CLASS OF 1991: OUR 47 5 MINUTES WITH… Leeds Festival. -

1.5K Campus Workout Guided Route

GET MOVING WITH SPORT LIVERPOOL THE BASICS A MAINLY FLAT, OUT-AND-BACK, RUN OR WALK FROM THE UNIVERSITY SPORTS & FITNESS CENTRE THROUGH ABRECROMBY SQUARE, 1.5k MULBERRY STREET, CATHERINE STREET AND FALKNER STREET, TO RICE STREET AND YE CRACKE PUB’, (JOHN LENNON’S OLD LOCAL) AND RETURN ALONG HOPE STREET TOWARDS LIVERPOOL METROPOLITAN CATHEDRAL, OXFORD STREET AND THE SPORTS CENTRE. INTERESTS ALONG THE WAY NOEL CHAVASSE SCULPTURE, ABERCROMBY SQUARE - THE BRONZE SCULPTURE IN ABERCROMBY SQUARE, BY LOCAL SCULPTOR TOM MURPHY, DEPICTS CAPTAIN NOEL CHAVASSE (1884-1917) AND A STRETCHER BEARER HELPING A WOUNDED SOLDIER TO SAFETY ON THE BATTLEFIELD OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR. FALKNER STREET IS ANOTHER PART OF THE ELEGANT DEVELOPMENT THAT ESTABLISHED ABERCROMBY SQUARE IN 1830. THIS ROUTE TAKES YOU PAST A LARGE, WALLED BUILDING, BLACKBURNE HOUSE, WHICH STANDS AT THE CORNER OF FALKNER STREET WITH HOPE STREET. IT WAS BUILT AROUND 1800 AS A GRAND PRIVATE RESIDENCE BUT IN 1844 IT BECAME THE GIRL’S SCHOOL OF THE MECHANICS INSTITUTE, LIVERPOOL’S FIRST GIRL’S SCHOOL. IT SUBSEQUENTLY BECAME THE LIVERPOOL INSTITUTE HIGH SCHOOL FOR GIRLS, THE SISTER SCHOOL TO THE NEARBY LIVERPOOL INSTITUTE HIGH SCHOOL FOR BOYS, PAUL MCCARTNEY AND GEORGE HARRISON OLD SCHOOL. FITTINGLY, BLACKBURNE HOUSE IS NOW A TRAINING AND EDUCATIONAL CENTRE FOR LOCAL WOMEN. RICE STREET, YE CRACKE PUB - THE PUB WAS ONCE A FAVOURITE OF STUDENTS AT THE LIVERPOOL COLLEGE OF ART, WHICH WAS SITUATED IN NEARBY MOUNT STREET. JOHN LENNON, AS A STUDENT THERE IN THE LATE 1950’S, WAS A REGULAR. REPUTEDLY, HE AND HIS FIRST WIFE, CYNTHIA, THEN ALSO AN ART STUDENT, WENT THERE ON THEIR FIRST DATE TOGETHER.