Women Participation in Selected Rural Development Programmes in the Nor Thern States of Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cholera Risk Assessment in Kano State, Nigeria: a Historical Review, Mapping of Hotspots and Evaluation of Contextual Factors

PLOS NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES RESEARCH ARTICLE The cholera risk assessment in Kano State, Nigeria: A historical review, mapping of hotspots and evaluation of contextual factors 1 2 2 2 Moise Chi NgwaID *, Chikwe Ihekweazu , Tochi OkworID , Sebastian Yennan , 2 3 4 5 Nanpring Williams , Kelly ElimianID , Nura Yahaya Karaye , Imam Wada BelloID , David A. Sack1 1 Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America, 2 Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, Abuja, Nigeria, 3 Department of a1111111111 Microbiology, University of Benin, Nigeria, 4 Department of Public Health and Disease Control, Kano State a1111111111 Ministry of Health, Kano, Nigeria, 5 Department of Public Health and Disease Control, Ministry of Health a1111111111 Kano, Kano, Nigeria a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Nigeria is endemic for cholera since 1970, and Kano State report outbreaks annually with Citation: Ngwa MC, Ihekweazu C, Okwor T, Yennan high case fatality ratios ranging from 4.98%/2010 to 5.10%/2018 over the last decade. How- S, Williams N, Elimian K, et al. (2021) The cholera ever, interventions focused on cholera prevention and control have been hampered by a risk assessment in Kano State, Nigeria: A historical lack of understanding of hotspot Local Government Areas (LGAs) that trigger and sustain review, mapping of hotspots and evaluation of contextual factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 15(1): yearly outbreaks. The goal of this study was to identify and categorize cholera hotspots in e0009046. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. Kano State to inform a national plan for disease control and elimination in the State. -

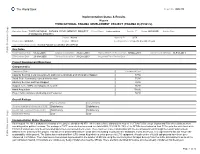

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR4370 Implementation Status & Results Nigeria THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (FADAMA III) (P096572) Operation Name: THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 7 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: (FADAMA III) (P096572) Country: Nigeria Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): National Fadama Coordination Office(NFCO) Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Jul-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date 07-Nov-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 11-Feb-2011 Effectiveness Date 23-Mar-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Capacity Building, Local Government, and Communications and Information Support 87.50 Small-Scale Community-owned Infrastructure 75.00 Advisory Services and Input Support 39.50 Support to the ADPs and Adaptive Research 36.50 Asset Acquisition 150.00 Project Administration, Monitoring and Evaluation 58.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Low Low Implementation Status Overview As at August 19, 2011, disbursement status of the project stands at 46.87%. All the states have disbursed to most of the FCAs/FUGs except Jigawa and Edo where disbursement was delayed for political reasons. The savings in FUEF accounts has increased to a total ofN66,133,814.76. 75% of the SFCOs have federated their FCAs up to the state level while FCAs in 8 states have only been federated up to the Local Government levels. -

The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival

n the basis on solid fieldwork in northern Nigeria including participant observation, 18 Göttingen Series in Ointerviews with Izala, Sufis, and religion experts, and collection of unpublished Social and Cultural Anthropology material related to Izala, three aspects of the development of Izala past and present are analysed: its split, its relationship to Sufis, and its perception of sharīʿa re-implementation. “Field Theory” of Pierre Bourdieu, “Religious Market Theory” of Rodney Start, and “Modes Ramzi Ben Amara of Religiosity Theory” of Harvey Whitehouse are theoretical tools of understanding the religious landscape of northern Nigeria and the dynamics of Islamic movements and groups. The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival Since October 2015 Ramzi Ben Amara is assistant professor (maître-assistant) at the Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Sousse, Tunisia. Since 2014 he was coordinator of the DAAD-projects “Tunisia in Transition”, “The Maghreb in Transition”, and “Inception of an MA in African Studies”. Furthermore, he is teaching Anthropology and African Studies at the Centre of Anthropology of the same institution. His research interests include in Nigeria The Izala Movement Islam in Africa, Sufism, Reform movements, Religious Activism, and Islamic law. Ramzi Ben Amara Ben Amara Ramzi ISBN: 978-3-86395-460-4 Göttingen University Press Göttingen University Press ISSN: 2199-5346 Ramzi Ben Amara The Izala Movement in Nigeria This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Published in 2020 by Göttingen University Press as volume 18 in “Göttingen Series in Social and Cultural Anthropology” This series is a continuation of “Göttinger Beiträge zur Ethnologie”. -

Assessment of Reasons for Oral Polio Vaccine Refusals in Bebeji Local Government Area, Kano State, Northern Nigeria, 2013

Texila International Journal of Public Health Volume 7, Issue 4, Dec 2019 Assessment of Reasons for Oral Polio Vaccine Refusals in Bebeji Local Government Area, Kano State, Northern Nigeria, 2013 Article by Musa K. Bawa1, Endie Waziri1, Aisha Mamman2, Suleiman Haladu1, Kabir Getso3, 1 Chima Ohuabunwo 1African Field Epidemiology Network (AFENET), Abuja, Nigeria, [email protected] 2Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital, Shika, Zaria, [email protected] 3Kano State Ministry of Health, Kano, Nigeria, [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Background: By 2013, Kano State was the hub of polio transmission in Nigeria. Polio campaign monitoring data indicated a high proportion of Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV) refusals were emerging as a major impediment to polio eradication in Nigeria particularly in Kano state. We conducted a qualitative study to identify reasons for OPV refusals and effective methods to improve OPV acceptance. Methods: We conducted In-depth interview (IDI) using a structured guide. We identified non-compliant households using vaccination tally sheets and interviewed male or female caregivers who had refused OPV for their children at least once in the previous supplemental immunization activities (SIA). Results: Seventeen interviews were conducted across the LGA. Of the 17 respondents, 13 (76.5%) were males. On the question” Is polio a significant health problem in the community” 14 (82.4%) answered no and explained that it should not be a priority but other more serious and prevalent diseases, 3(17.6%) answered yes and explained that it is a significant health problem since they have seen few cases. On why they refused OPV, about half felt there were other more important community needs, three felt they had no need for OPV and lacked trust in Government, five were worried the vaccine may be harmful. -

COVID-19 Response Coordination and Surveillance - Kano State Experience Kano State Socio‐Demographics

Nigeria Centre for Disease Control Protecting the health of Nigerians COVID-19 Response Coordination and surveillance - Kano State experience Kano State Socio‐demographics o LGAs: 44 o Total population of 14,311,254 o Public health facilities: 1224 o Private health facilities: 156 o International airport o 8 LGAs in the metropolis o Constitute 30% of total population Kano state COVID-19 Response Structure xx Team lead Kano State Taskforce on COVID-19 (HE Deputy Governor) (Chairman) IM Support team Coordinator/Incident manager (Dr Tijjani Hussaini) EOC Operations Liaison with partners Lead research Deputy Coordinator Follow up of plans (Dr Sabitu Y. Shuaibu) Data management Surveillance / Laboratory Case management Infection and Risk Logistics Epidemiology prevention control communication Dr Ibrahim Auwalu Abullahi Pharm. Isah Bala Dr Bashir Lawan Hamza Shuaibu Nashabru Prof. Yusuf Sabo Fagge Case investigation Sample collection Coordination of COVID-19 frontline Risk communication Inventory treatment in isolation team system management and quarantine Contact tracing and Sample centers Community Commodity pick up team management engagement distribution Connect Center Quality assurance Welfare of patients Supervision and Public information Commodities and the case monitoring ( 1º,2º storage management team and 3º Active case Sample shipment Media engagement Equipment research maintenance Burial of confirmed Point of entry Sample reporting or suspected cases Stock management | 3 Key Timelines In Kano Response 7th January 11th April 21st April China confirmed corona Kano detected first case 2017 Inaugurated a new IMS virus, has been (Index case) identified to cause structure COVID 19 th 20th March 12th April 27 February 17th April Kano State activated Response, contact Nigeria detected it’s EOC shut as members & IMS for covid 19 tracing & other first case (Index case) task force team test +ve surveillance activities commenced NIGERIA CENTRE FOR DISEASE CONTROL 4 Intensified Surveillance Activities The picture can't be displayed. -

Download Download

Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography Volume 2 1997 FOREIGN PERIODICALS ON AFRICA Foreign Periodicals on Africa John Bruce Howell∗ ∗University of Iowa Copyright c 1997 by the authors. Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography is produced by Iowa Research Online. http://ir.uiowa.edu/ejab/vol2/iss1/1 Volume 2 (1997) Foreign Periodicals on Africa John Bruce Howell, International Studies Bibliographer, University of Iowa Libraries Contents 1. Abia State (Nigeria) Approved estimates of Abia State of Nigeria. -- Umuahia: Govt. Printer,(Official document) 1992, 1993 (AGR5306) 2. Abia State (Nigeria) Authorised establishments of Abia state civil service...fiscal year: special analysis of personnel costs. -- Umuahia, Abia State, <Nigeria>: Burueau of Budget and Planning, Office of the Governor. 1992 (AGR5299) 3. Abinibi. Began with Nov. 1986 issue. -- Lagos: Lagos State Council for Arts and Culture, v. 2: no.1-4, v.4:no.1 (AGD3355) 4. Aboyade, Ojetunji. Selective closure in African economic relations / by Ojetunji Aboyade. -- Lagos: Nigerian Institute of International Affairs, 1991. (Lecture series, 0331-6262; no. 69) (AGN9665) 5. Abubakar, Ayuba T. Planning in strategic management. -- Topo, Badagry: ASCON Publications, 1992. (Occasional papers / Administrative Staff College of Nigeria; 5.) (AGN9807) 6. Academie malgache. Bulletin. v. 1-12, 1902-13; new ser., t.1- 1914- -- Tananarive. (AGD1928) 7. Academie malgache. Bulletin d'information et de liaison / Academie malgache. -- Antananarivo: L'Academie,. v. 5, 7-10, 12, 16-17, 19 (AGD2020) 8. ACMS staff papers / Association of African Central Banks. Began in 1988? -- Dakar, Senegal: The Association, v.1:no. 4., no.5 (AGK8604) 9. Actualites Tchadiennes. -- <N'Djamena>: Direction de la presse a la presidence de la republique. -

Access Bank Branches Nationwide

LIST OF ACCESS BANK BRANCHES NATIONWIDE ABUJA Town Address Ademola Adetokunbo Plot 833, Ademola Adetokunbo Crescent, Wuse 2, Abuja. Aminu Kano Plot 1195, Aminu Kano Cresent, Wuse II, Abuja. Asokoro 48, Yakubu Gowon Crescent, Asokoro, Abuja. Garki Plot 1231, Cadastral Zone A03, Garki II District, Abuja. Kubwa Plot 59, Gado Nasko Road, Kubwa, Abuja. National Assembly National Assembly White House Basement, Abuja. Wuse Market 36, Doula Street, Zone 5, Wuse Market. Herbert Macaulay Plot 247, Herbert Macaulay Way Total House Building, Opposite NNPC Tower, Central Business District Abuja. ABIA STATE Town Address Aba 69, Azikiwe Road, Abia. Umuahia 6, Trading/Residential Area (Library Avenue). ADAMAWA STATE Town Address Yola 13/15, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola. AKWA IBOM STATE Town Address Uyo 21/23 Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom. ANAMBRA STATE Town Address Awka 1, Ajekwe Close, Off Enugu-Onitsha Express way, Awka. Nnewi Block 015, Zone 1, Edo-Ezemewi Road, Nnewi. Onitsha 6, New Market Road , Onitsha. BAUCHI STATE Town Address Bauchi 24, Murtala Mohammed Way, Bauchi. BAYELSA STATE Town Address Yenagoa Plot 3, Onopa Commercial Layout, Onopa, Yenagoa. BENUE STATE Town Address Makurdi 5, Ogiri Oko Road, GRA, Makurdi BORNO STATE Town Address Maiduguri Sir Kashim Ibrahim Way, Maiduguri. CROSS RIVER STATE Town Address Calabar 45, Muritala Mohammed Way, Calabar. Access Bank Cash Center Unicem Mfamosing, Calabar DELTA STATE Town Address Asaba 304, Nnebisi, Road, Asaba. Warri 57, Effurun/Sapele Road, Warri. EBONYI STATE Town Address Abakaliki 44, Ogoja Road, Abakaliki. EDO STATE Town Address Benin 45, Akpakpava Street, Benin City, Benin. Sapele Road 164, Opposite NPDC, Sapele Road. -

Economics of Groundnut Production in Dambatta Local Government Area of Kano State, Nigeria

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS) |Volume IV, Issue IX, September 2020|ISSN 2454-6186 Economics of Groundnut Production in Dambatta Local Government Area of Kano State, Nigeria Godfrey Onuwa1*, Ibiyinka Ademiluyi1, Grace Yitnoe2 1Department of Agricultural Extension and Management, Federal College of Forestry, Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria 2 Entrepreneurship and Consultancy Unit, Federal College of Forestry, Jos, Plateau state, Nigeria *Corresponding author Abstract: This study analyzed the economics of groundnut pressing out the oil is used in feeding livestock. Groundnut production in Dambatta Local Government Area of Kano state, kernel also provides nutritious fodder (haulms) to in livestock Nigeria. Multi-stage sampling technique was adopted. Primary rations. Also the leaves and straws are used in feeding data were collected using structured questionnaires. Descriptive livestock in their green and dry forms or in making chipboard and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data collected. for use in joinery ([II]; [VII]; [VIII]). It is also processed into The results of the study revealed that the socioeconomic factors of the respondents significantly affected groundnut production in or included as an ingredient in a wide range of other products the study area. The gross margin and net farm income were and local diets which includes; groundnut paste, groundnut estimated as ₦59,850/ha and ₦47,350/ha respectively. The cake (kulikuli), groundnut porridge made with millet (kunun estimated benefit cost ratio was 1.75. A gross ratio of 0.57 was gyada), groundnut candy (kantun gyada) and groundnut soup recorded (a ratio of ˂1 is desirable). The estimates of operating (miyar gyada). -

Combating Wildlife Crime in Nigeria an Analysis of the Criminal Justice Legislative Framework

Wildlife Combating Wildlife Crime in Nigeria An analysis of the Criminal Justice Legislative Framework August 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CITATION GLOSSARY We would Shamini Jayanathan, Barrister-at- ACJA - Administration of Criminal like to thank Law, Arcturus Consultancy Ltd. May Justice Act our donor, 2021. Combating Wildlife Crime in the Bureau of Nigeria: An Analysis of the Criminal AG - Attorney General International Justice Legislative Framework. AGF - Attorney General of the Federation Narcotics and Law Enforcement Africa Nature Investors Foundation Affairs within the U.S. Department and Environmental Investigation ANI - Africa Nature Investors Foundation of State, which funded the Agency (UK). CBB - Code of Conduct Bureau production of this report. CCG - Complex Case Group In addition, we would like to This report was funded by a grant CITES - Convention on International thank all of the many individuals, Trade in Endangered Species of Wild from the United States Department Fauna and Flora government agencies and non- of State. The opinions, findings governmental organisations that and conclusions stated herein are DPP - Office of the Director of Public contributed to this report, including those of the author[s] and do not Prosecutions [Nigeria] but not limited to representatives necessarily reflect those of the ECOWAS - Economic Community of West from the Convention on United States Department of State African States International Trade in Endangered EFCC - Economic and Financial Crimes Species of Wild Fauna and Flora ABOUT ANI (CITES) -

2018 Issn: 2456-8643

International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Bioresearch Vol. 3, No. 06; 2018 ISSN: 2456-8643 SOURCES OF INFORMATION TO CLIMATE EVENTS AND ADOPTION OF COPING PRACTICES BY ARABLE CROPS FARMERS IN KANO STATE NIGERIA 1Abbas, M.N.,2Aminu, H., 3Ahmed,S.S.,4Abubakar,R.A.,5Sabo,U.I.,6Barkindo, M. A. 1,3,5 Agricultural Economics Extension and Management 4Agricultural-Bioenvironmental Engineering 2,6 General and remedial Studies Audu Bako College of Agriculture Dambatta P.M.B.3159, Kano State, Nigeria ABSTRACT Agriculture is among factors affecting environment in satisfying human daily needs which tremendously contributes to climate change, to help in understanding of change farmers’ perception of climate change and knowledge sources at local levels were examined. A total 250 farmers were sampled through stratified random sampling techniques. The data and information gathered via returned instruments (88%) were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics. The results revealed that male respondents accounted for 92.2% as the majority while female farmers accounted for 7.8% of farmers and mean(33) years. More than 86.53% had education background, 75.46% perceived changes in temperature, wind action (8.18%), sunlight (86.3%),flood and change in the rainy days(90.9%) while (74.55) of farmers had changed their cropping patterns,42.8% farmers obtained their information on climate change from extension agents (22.3%) while 17.8% acquired Knowledge from interactions of friends and families and NGOs(.4%).Cover cropping(80.90%)5th, planting economic trees(82.47%)4th,mixed farming (77.27%)7th and early maturing vanities(1965)1st and other practices were adopted in coping with changes. -

17 Meeting of the Expert Review Committee (ERC) on Polio Eradication & Routine Immunization in Nigeria

17th Meeting of the Expert Review Committee (ERC) On Polio Eradication & Routine Immunization in Nigeria Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria 1 - 2 April 2009 1 Executive Summary The ERC is very encouraged by the substantial advances that have been made in the polio eradication effort in Nigeria since the last meeting of the Committee in October 2008. Most striking, many of these advances were evident at the national, state and LGA levels and across a range of areas that included political support, traditional leader engagement, and quality of IPD operations. In stark contrast to the situation at a number of previous meetings, the ERC noted that close attention had been given to the systematic implementation of the recommendations of the 16 th ERC at the federal level and in most states. The most striking, concrete evidence of the impact of this work is that in the 1st quarter of 2009, for the first time in the history of the programme, the proportion of 'zero-dose' children in nearly all states in the country was below 20%. Particularly important and laudable was the achievement of this milestone in Kano State. The Committee highlighted, however, that Nigeria still has the highest burden of polio in the world. Although the wild poliovirus type 1 epidemic of 2008 is subsiding in the north of the country, there was an upsurge of type 3 cases in these states in the 1 st quarter of 2009 and the type 2 circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) continues, making this the only area in the world where children continue to be paralyzed by all three types of poliovirus. -

IOM Nigeria DTM Flash Report NCNW 23 August 2021

FLASH REPORT #66: POPULATION DISPLACEMENT DTM North West/North Central Nigeria Nigeria 16 - 22 AUGUST 2021 Aected Population: Damaged Shelters: Casualties: Movement Trigger: 3,161 Individuals 56 133 Armed attacks/Rainstorms OVERVIEW AFFECTED LOCATIONS Nigeria's North Central and North West Zones are afflicted with a mul�dimensional crisis that is rooted in long-standing tensions between ethnic and religious groups and involves a�acks by criminal groups and banditry/hirabah (such as kidnapping and grand larceny along major highways). The crisis has accelerated during the past NIGER REPUBLIC years because of the intensifica�on of a�acks and has resulted in widespread displacement across the region. Between 16 and 22 August 2021, armed clashes between herdsmen and farmers; and bandits and local communi�es as well as rainstorms have led to new waves of Sokoto popula�on displacement. Following these events, rapid assessments were conduct- ed by DTM (Displacement Tracking Matrix) field staff with the purpose of informing Batsari the humanitarian community and government partners, and enable targeted 1,617 14 response. Flash reports u�lise direct observa�on and a broad network of key infor- Kusada mants to gather representa�ve data and collect informa�on on the number, profile Katsina and immediate needs of affected popula�ons. Jigawa Zamfara Bukkuyum During the assessment period, the DTM iden�fied an es�mated number of 3,161 124 1,002 Kano individuals who were displaced to neigbouring wards. Of the total number of Faskari Kebbi Kiru displaced individuals, 2,864 persons were displaced because of communal clashes 198 Dandume in the LGAs Sabuwa, Dandume, Faskari and Batsari in Katsina State and Bukkuyum Sabuwa 19 LGA of Zamfara State.