Ahnational Quali Cations SPECIMEN ONLY SQ19/AH/01 History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(2014) Dlùth Is Inneach: Linguistic and Institutional Foundations for Gaelic Corpus Planning

Bell, S., McConville, M., McLeod, W., and O Maolalaigh, R. (2014) Dlùth is Inneach: Linguistic and Institutional Foundations for Gaelic Corpus Planning. Project Report. Copyright © 2014 The Authors and Bord na Gaidhlig A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge The content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/98132/ Deposited on: 14 October 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Dlùth is Inneach – Final Project Report Linguistic and Institutional Foundations for Gaelic Corpus Planning Prepared for Bòrd na Gàidhlig (Research Project no. CR12-03) By Soillse Researchers Susan Bell (Research Assistant, University of Glasgow) Dr Mark McConville (Co-investigator, University of Glasgow) Professor Wilson McLeod (Co-investigator, University of Edinburgh) Professor Roibeard Ó Maolalaigh (Principal Investigator, University of Glasgow) Expert Adviser: Professor Robert Dunbar, University of Edinburgh Co-ordinator: Iain Caimbeul, Sabhal Mòr Ostaig UHI 27 January 2014 Redacted version for publication GEÀRR-CHUNNTAS GNÌOMHACH Is e tha san aithisg seo toraidhean bho phròiseact bliadhna a rinn sgioba rannsachaidh Shoillse às leth Bhòrd na Gàidhlig (BnG). B’ e amas an rannsachaidh fuasgladh fhaighinn air a' cheist a leanas: Cò na prionnsapalan planadh corpais as fheàrr a fhreagras air neartachadh agus brosnachadh -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten MacGregor, Martin (2009) Gaelic barbarity and Scottish identity in the later Middle Ages. In: Broun, Dauvit and MacGregor, Martin(eds.) Mìorun mòr nan Gall, 'The great ill-will of the Lowlander'? Lowland perceptions of the Highlands, medieval and modern. Centre for Scottish and Celtic Studies, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, pp. 7-48. ISBN 978085261820X Copyright © 2009 University of Glasgow A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/91508/ Deposited on: 24 February 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages MARTIN MACGREGOR One point of reasonably clear consensus among Scottish historians during the twentieth century was that a ‘Highland/Lowland divide’ came into being in the second half of the fourteenth century. The terminus post quem and lynchpin of their evidence was the following passage from the beginning of Book II chapter 9 in John of Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum, which they dated variously from the 1360s to the 1390s:1 The character of the Scots however varies according to the difference in language. For they have two languages, namely the Scottish language (lingua Scotica) and the Teutonic language (lingua Theutonica). -

The Wild Irish

Hybernos Sylvestres: Ireland and the Irish in Polydore Vergil’s Anglica historia (1534) and Paolo Giovio’s Descriptio Britanniaiae, Scotiae, Hyberniae et Orchadum (1548) Ireland had been of little interest to foreign writers since the publication of Giraldus Cambrensis’ The History and Topography of Ireland in the twelfth century. However, the first modern descriptions of Ireland were produced in the sixteenth century by two Italian historians. Polydore Vergil’s Anglica historia (1534) and Paolo Giovio’s Descriptio Britanniaiae, Scotiae, Hyberniae et Orchadum (1548) include original descriptions of Ireland and the Irish. Both representations exemplify many of the characteristics of Renaissance cosmography and ethnography. Thus, the texts are punctuated with references to specific classical antecedents, while classical cosmographical and ethnographical concepts and parameters are utilised to describe the island of Ireland and its inhabitants. However, Vergil and Giovio present two distinct descriptions of Ireland which are notable for their differences rather than their similarities. Moreover, the representations of the Irish people presented by each writer are diametrically opposed: Vergil’s description is from a colonial perspective and negative while Giovio’s is positive; a rare example of a non-colonial ethnographical account of Irish identity.1 This article will examine the representation of Irish identity in the Anglica historia and the Descriptio Britanniaiae, Scotiae, Hyberniae et Orchadum respectively.2 Firstly, it will briefly contextualise both texts and their authors. Next, it will examine how the classical ethnographic model was utilised in a sixteenth century context, to present conflicting and contrasting representations of the Irish people. Finally, it will analyse Vergil’s use of the classical antithesis between civilised and barbarous languages in the representation of Irish identity presented in the Anglica historia. -

Historyofscotlan10tytliala.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

Act II, Signature Xvii - (1)

We can also trace that peculiar social movement which led some factories, ships, restaurants, and households to clean up their backstages to such an extent that, like monks, Communists, or German aldermen, their guards are always up and there is no place where their front is down, while at the same time members of the audience become sufficiently entranced with the society's id to explore the places that had been cleaned up for them [Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self (New York: Anchor Press, 1959), p. 247]. II — xvii — What Was That Good For? Coalition forces pour into Ossian. In Las Vegas, Roveretto Messimo ponders taking on a new client to pay his bills. A U.S. detachment breaks into the Impersonal Terrace while Fuald, deported back to Ossian, plots revenge by organizing the looting of the Hermitage. Charles, drugged by Ferguson’s alien soporifics, agrees to print an article exposing the eco– terrorist aims of the Founder’s League. In the 13th century, the fanatical inquisitor Conrad prepares to declare anathema against Fr. Anselm. ~ page 215 ~ This is the cover art for the single "War" by the artist Edwin Starr. The cover art copyright is believed to belong to the label, Gordy, or the graphic artist.* "War" Act II, Signature xvii - (1) *[Image & caption credit and following text courtesy of Wikipedia]: "War" is a soul song written by Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong for the Motown label in 1969. Whitfield first produced the song — a blatant anti-Vietnam War protest — with The Temptations as the original vocalists. After Motown began receiving repeated requests to release "War" as a single, Whitfield re-recorded the song with Edwin Starr as the vocalist, deciding to withhold the Temptations ' version so as not to alienate their more conservative fans. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE COURT OF THE COMMISSARIES OF EDINBURGH: CONSISTORIAL LAW AND LITIGATION, 1559 – 1576 Based on the Surviving Records of the Commissaries of Edinburgh BY THOMAS GREEN B.A., M.Th. I hereby declare that I have composed this thesis, that the work it contains is my own and that this work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification, PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2010 Thy sons, Edina, social, kind, With open arms the stranger hail; Their views enlarg’d, their lib’ral mind, Above the narrow rural vale; Attentive still to sorrow’s wail, Or modest merit’s silent claim: And never may their sources fail! And never envy blot their name! ROBERT BURNS ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines the appointment of the Commissaries of Edinburgh, the court over which they presided, and their consistorial jurisdiction during the era of the Scottish Reformation. -

Gaels, Galls and Overlapping Territories in Late Medieval Ireland

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Cultural geographies of the contact zone: Gaels, Galls and overlapping territories in late medieval Ireland Author(s) Morrissey, John Publication Date 2005 Publication Morrissey J. (2005) 'Cultural geographies of the contact zone: Information Gaels, Galls and overlapping territories in late medieval Ireland', Social and Cultural Geography, 6(4): 551-566 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/834 Downloaded 2021-09-27T03:27:19Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. John Morrissey 1 Cultural geographies of the contact zone: Gaels, Galls and overlapping territories in late medieval Ireland John Morrissey Department of Geography, National University of Ireland, Galway, University Road, Galway, Ireland. Tel.: 353 91 492267. Fax: 353 91 495505. E-mail: [email protected] In writing about the social and cultural geographies of the past, we frequently reinforce notions of difference by using neatly delineated ethnic terms of reference that often superscribe the complexities of reality on the ground. Referring to ‘Gaels’ and ‘Galls’, demarcating ‘native’ and ‘foreign’ worlds in late medieval Ireland, is but one example. We often exaggerate, too, the boundedness of geographical space by speaking more of frontiers and less of overlapping territories. Using the context of late medieval Ireland, I propose in this paper the application and broadening of the concept of the contact zone – prevalent in postcolonial studies for a number of years – to address this specific issue of overstating social and cultural geographical cohesion and separation in the past. -

THE SUCCESSION and FOREIGN POLICY , By: Adams, Simon, History Today, 00182753, May2003, Vol

Title: THE SUCCESSION AND FOREIGN POLICY , By: Adams, Simon, History Today, 00182753, May2003, Vol. 53, Issue 5 THE SUCCESSION AND FOREIGN POLICY Simon Adams looks at the close connections between Elizabeth's ascendancy, her religion and her ensuing, relationships with the states of Europe. 'She is a very prudent and accomplished princess, who has been well educated, she plays all sorts of instruments and speaks several languages (even Latin) extremely well. Good-natured and quick spirited, she is a woman who loves justice greatly and does not impose on her subjects. She was good-looking in her youth, but she is also tight-fisted to the point of avarice, easily angered and above all very jealous of her sovereignty.' THIS ASSESSMENT OF Elizabeth I was made in the introductory discourse to his collected papers by Guillaume de d'Aubespine, Baron de Châteauneuf, ambassador from Henry III of France between 1585 and 1590. Given that Châteauneuf's embassy had involved him in the diplomatic nightmare of the trial and execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, it was a remarkably charitable description. But it was not untypical of the respect and even admiration in which Elizabeth was held by French ambassadors to her court. Thanks to the agreement to exchange resident ambassadors that Henry VIII and Francis I made in the Treaty of London of October 1518, the French crown maintained the only permanent embassy of Elizabeth's reign. Unfortunately, accidents of archival survival have left large gaps in the French ambassadorial correspondence and only a small amount has been published. By contrast the Spanish ambassadorial correspondence of the reign was published in full over a century ago, first in Spanish and then in English. -

Cultural Glocalization Or Resistance? Interrogating the Title Production of Youtube Videos at an Irish Summer College Through Practice-Based Research

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Cultural glocalization or resistance? Interrogating the Title production of YouTube videos at an Irish summer college through practice-based research Author(s) Mac Dubhghaill, Uinsionn Publication Date 2017-03 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/6912 Downloaded 2021-09-28T20:59:24Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Cultural glocalization or resistance? Interrogating the production of YouTube videos at an Irish summer college through practice-based research Uinsionn Mac Dubhghaill B.A., H.Dip. in Ed., M.A. This thesis is submitted for the degree of PhD Huston School of Film & Digital Media National University of Ireland, Galway March 2017 Supervisors Prof. Rod Stoneman & Dr. Seán Crosson In Memoriam Vincent Mac Dowell (1925–2003) ‘When I was a child, my father would recount how the power, wealth and status of the high priests in ancient Egypt derived from their ability to predict the annual Nile floods, essential to the country’s agricultural economy. The priests derived this knowledge from astronomical observations and a system for monitoring river levels, but hid it in arcane language and religious symbolism in order to maintain their power, and pass it on to their children. He told us this story in order to teach us to question the language the elites use in order to preserve their own privileges.’ This thesis document, pp. 95-96 i DECLARATION This thesis is submitted in two parts. The first part is a body of creative practice in film, and the second part is this written exegesis. -

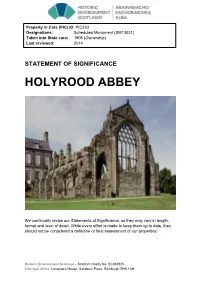

Holyrood Abbey Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC223 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13031) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HOLYROOD ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HOLYROOD ABBEY SYNOPSIS The Augustinian Abbey of Holyrood was founded by David I in 1128 as a daughter-house of Merton Priory (Surrey). By the 15th century the abbey was increasingly being used as a royal residence – James II was born there in 1430 - and by the time of the Protestant Reformation (1560) much of the monastic precinct had been subsumed into the embryonic Palace of Holyroodhouse. -

Bonnie Scotland and La Belle France: Commonalites and Cultural Links

Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 5 May 2013 Bonnie Scotland and La Belle France: Commonalites and cultural links. Moira Speirs MS Oglethorpe University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur Part of the European History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Speirs, Moira MS (2013) "Bonnie Scotland and La Belle France: Commonalites and cultural links.," Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol2/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bonnie Scotland and La Belle France: Commonalites and cultural links. Cover Page Footnote With thanks to Emily Winkler, Jesus college, Oxford and Anne Salter, Oglethorpe University, Atlanta Georgia This article is available in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol2/iss1/5 Speirs: Scotland and France: Commonalites and cultural links. The Auld Alliance between Scotland and France was ratified by treaty many times in history.1After 1603 with the union of the crowns of Scotland and England, it was never again a formal alliance. However the Auld Alliance did not die, the continuing links between the two countries shaped many aspects of their society. Trade, education, language, law, and philosophy were influenced by the cultural links and friendships between Scotland and France.