Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Tazewell County Warren County Westmoreland~CO~Tt~~'~Dfla

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. Tazewell County Warren County Westmoreland~CO~tt~~'~dfla Bedford Bristol Buena Vista Charl~esville ~ake clnr(~ F:Org I Heights Covington Danville Emporia Fairfax Falls ~.~tur.~~l~).~ ~urg Galax Hampton HarrisonburgHopj~ll~l Lexingtor~ynchburgl~'~assa ~ anassas Martinsville Newport News Norfolk Norton PetersbutrgPoque~o~ .Portsmouth Radford Richmond Roano~l~~ Salem ~th Bostor~t~nto SuffoLk Virginia Beach Waynesboro Williamsburg Winchester ~a~:~ingham Ceuul~ Carroll County Charlotte County Cra~ Col~ty Roar~ County~cco~Lac= Albemarle County Alleghany County Amelia County#~rlb~ ~NJ~/Ly,~ll~iatt~ County Arlington CountyAugula County Bath i~nty BerJ~rd Cd~t B.I.... ~1 County Botetourt County Brunswick County Buchanal~C~ut~ ~~wrtty Caroline County Charles City C~nty Ch~erfield~bunty C~rrke Co~t CT~-~eperCounty Dickenson County Dinwiddie County~ ~~~ r-'luvanneCounty Frederick County C~ucester (~unty C~yson (j~nty Gre~=~ County Greensville County Halifax County Hanover County ~ .(D~I~ I~liry Cottnty Highland County Isle of *~.P-.o.~t~l~me~y C~ ~county King George County King William County~r .(~,t~ ~ (~'~ Loudoun County Louisa County M~ Mat~s Cot]1~l~~ qt... ~ Montgomery County New Kent County North~ur~d County N~y County Page County Pittsylvania CouniY--Powhatan]~.~unty Princ~eorg, oC'6-~ty Prince William County Rappahannock County Richmol~l 0~)1~1=I~Woo~ Gi0ochtandCounty Lunenburg County Mecklenburl~nty Nelson Count Northampton CountyOrange County Patrick CountyPdn¢~ -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

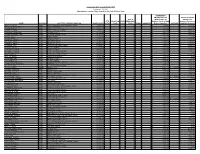

Public Act 097-0256 2018-2019.Pdf

Community Unit School District 300 Public Act 097-256 Administrator Teacher Salary Report for 2018-2019 School Year RETIREMENT ENHANCEMENTS OTHER BENEFITS SICK & (Board Paid TRS (Board Paid FTE VACATION FLEX PERSONAL Employee Portion, HRA Insurance Premiums, NAME POSITION JOB TITLE - PRIMARY POSITION BASE SALARY TOTAL DAYS DAYS DAYS BONUS ANNUITIES Retiree Deposits) MILEAGE HSA&HRA Deposits) ABOY, CRISTINA LEAD ELEM Kindergarten Dual Language Teacher $ 70,301.02 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,950.08 $ 5,723.59 ABRAHAM, CATHERINE LEAD Speech Pathologist $ 57,672.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,285.39 $ 33.60 ADAME, SHILOH LEAD MS Language Arts Teacher $ 65,022.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,672.24 $ 13,263.17 ADAMS, BELINDA LEAD Behavior Disorder Teacher $ 70,301.02 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,950.08 $ 19,970.00 ADAMSON, STEPHANIE LEAD MS Math Teacher $ 52,852.00 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,031.71 $ 19,874.36 ADAMS-WHITSON, VICKI LEAD Cross Catergorical Teacher $ 51,817.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,977.23 $ 6,079.03 ADKINS, HOLLY LEAD Media Teacher $ 44,292.00 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,581.18 $ 33.60 ADLER, LEIGH LEAD School Counselor $ 89,264.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 4,948.14 $ 19,962.08 AGARWAL, MEENU LEAD MS ESL Teacher $ 58,802.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,344.87 $ 192.72 AGENEAU, CARIE LEAD HS French Teacher $ 51,875.02 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,980.29 $ 5,763.19 AGENEAU, EMMA LEAD HS Spanish Teacher $ 50,859.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,926.81 $ 5,763.19 AGENLIAN, JULI LEAD ELEM Second Grade Teacher $ 58,892.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,349.60 $ 19,802.96 AGUILAR, NICOLE LEAD MS ESL Teacher $ 60,070.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,411.60 $ 13,263.17 AGUINAGA, -

RESOURCES NATURAL Divisto~OF Geologicala CEOPHYSKAL SURVEYS RESOURCES

Published by STATEOF ALASKA Abska Department of DEPARTMENTOF NATURAL RESOURCES NATURAL Divisto~OF GEOLOGICALa CEOPHYSKAL SURVEYS RESOURCES 1996 /rice: $5.00 - -- .-. -- -- - -A-- - - - - - - - Information Circular 11 PUBLICATIONSCATALOG OF THE DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL& GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS Fourth Edition Published by STATEOF ALASKA DEPARTMENTOF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISIONOF GEOLOGICAL& GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS DEDICATION All of us who have had the pleasure of working with Roberta (Bobbi) Mann are indeed fortunate. Without exception, we have found her to be industrious, dedicated, efficient, and of unflagging good humor. Fully half of the publications listed in this brochure couldn't have been produced without her. STATE OF ALASKA For over 20 years, Bobbi has routinely typed (and corrected) Tony Knowles, Governor all the sesquipedalian buzzwords in the geologist's lexicon, from allochthonous to zeugogeosyncline (with stops at DEPARTMENT OF hypabyssal and poikiloblastic)-without having even the NATURAL RESOURCES remotest idea of their meaning. John T. Shively, Commissioner DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL & Such zeal. Bobbi has spent most of her adult life typing error- GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS free documents about an arcane subject she knows virtually Milton A. Wiltse, Acting Director and nothing about. If, at the end of her career, someone would ask State Geologist her what she spent the last few decades typing, I'm positive Bobbi would shyly smile and say, "I'm not really sure. Some- Publication of DCCS reports is required by thing about rocks." Alaska Statute 41, "to determine the poten- tial ofAlaskan land for production of metals, minerals, fuels, and geothermal resources; Now THAT'S dedication. the location and supplies of groundwater and construction materials; the potential geologic hazardsto buildings, roads, bridges, and other installations and structures; and . -

Individual and Multitude in Roberto Bolaño's 2666 By

The Invisible Crowd: Individual and Multitude in Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 by Francisco Brito A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Francine Masiello, Chair Professor Estelle Tarica Professor Tom McEnaney Summer 2018 The Invisible Crowd: Individual and Multitude in Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 ¬ 2018 Francisco Brito 1 Abstract The Invisible Crowd: Individual and Multitude in Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 by Francisco Brito Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Francine Masiello, Chair This dissertation argues that Roberto Bolaño’s novel 2666 offers us a new way of thinking about the relationship between the individual and the multitude in the globalized world. I argue that the novel manages to capture the oppressive nature of its structures not by attempting to represent them directly but instead by telling the stories of individuals who feel especially alienated from them. These characters largely fail to connect with one another in any lasting way, but their brief encounters, some of which take place in person, others through reading, have pride of place in a text that, I propose, constitutes a brief on behalf of the marginal and the forgotten in its overall form: it is an example of the novel as an ever-expanding, multitudinous crowd; it strives to preserve the singularity of each of its members while at the same time suggesting that the differences between them are less important than their shared presence within a single narrative whole. -

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Picking a book to read? Check the Accelerated Reader quiz list below and choose a book that will count for credit in grade 7 or grade 8 at Quabbin Middle School. Please see your teacher if you have questions about any selection. The most recently added books/tests are denoted by the darkest blue background as shown here. Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 8451 EN 100 Questions and Answers About AIDS Ford, Michael Thomas 7.0 8.0 101453 EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 5.0 9.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.2 16.0 9201 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Clare, Andrea M. 4.3 2.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 4.1 2.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 7.1 8.0 59347 EN 5 Ways to Know About You Gravelle, Karen 8.3 5.0 8851 EN A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 7.6 12.0 81642 EN Abduction! Kehret, Peg 4.7 6.0 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette 6.8 9.0 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 6.2 3.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 5251 EN Acceptable Time, An L'Engle, Madeleine 7.5 15.0 5252 EN Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5.1 6.0 5253 EN Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 7.0 2.0 8452 EN Across America on an Emigrant Train Murphy, Jim 7.5 4.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 8.9 11.0 6901 EN Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 7.4 8.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary.. -

A Reader's Library: Hugh Nibley: a Legend in His Own Time

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 12 Number 1 Article 14 1-31-2003 A Reader's Library: Hugh Nibley: A Legend in His Own Time Mary Lythgoe Bradford Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Bradford, Mary Lythgoe (2003) "A Reader's Library: Hugh Nibley: A Legend in His Own Time," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 12 : No. 1 , Article 14. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol12/iss1/14 This Departments is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title A Reader’s Library: Hugh Nibley: A Legend in His Own Time Author(s) Mary Lythgoe Bradford Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 12/1 (2003): 108–10, 120. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract This review enthusiastically endorses Boyd Petersen’s biography of his father-in-law, Hugh Nibley. Petersen intersperses narrative chapters with thematic ones in Hugh Nibley: A Consecrated Life. A READER’S LIBRARY Mary Lythgoe Bradford Hugh Nibley: A Legend in His as a defender of the faith. I don’t I interviewed him for Dialogue, I Own Time disagree, but like most labels, these was impressed with his purple It is tempting to call Boyd Jay are too simplistic. As Bennion’s running shoes and his satirical Petersen’s book Hugh Nibley: A biographer, however, I noticed yet lovable personality. -

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

Modeling and Mapping of the Structural Deformation of Large Impact Craters on the Moon and Mercury

MODELING AND MAPPING OF THE STRUCTURAL DEFORMATION OF LARGE IMPACT CRATERS ON THE MOON AND MERCURY by JEFFREY A. BALCERSKI Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August, 2015 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Jeffrey A. Balcerski candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Committee Chair Steven A. Hauck, II James A. Van Orman Ralph P. Harvey Xiong Yu June 1, 2015 *we also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein ~ i ~ Dedicated to Marie, for her love, strength, and faith ~ ii ~ Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................1 2. Tilted Crater Floors as Records of Mercury’s Surface Deformation .....................4 2.1 Introduction ..............................................................................................5 2.2 Craters and Global Tilt Meters ................................................................8 2.3 Measurement Process...............................................................................12 2.3.1 Visual Pre-selection of Candidate Craters ................................13 2.3.2 Inspection and Inclusion/Exclusion of Altimetric Profiles .......14 2.3.3 Trend Fitting of Crater Floor Topography ................................16 2.4 Northern -

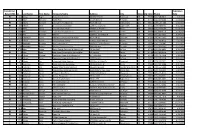

Installers.Pdf

Initial (I) or Expiration Recert (RI) Id Last Name First Sept Name Company Name Address City State Zip Code Phone Date RI 212 Abbas Roger Abbas Construction 6827 NE 33rd St Redmond OR 97756 (541) 548-6812 2/3/2024 I 2888 Adair Benjamin Septic Pros 1751 N Main st Prineville OR 97754 (541) 359-8466 5/10/2024 RI 727 Adams Kenneth Ken Adams Plumbing Inc 906 N 9th Ave Walla Walla WA 99362 (509) 529-7389 6/23/2023 RI 884 Adcock Dean Tri County Construction 22987 SE Dowty Rd Eagle Creek OR 97022 (503) 948-0491 9/25/2023 I 2592 Adelt Georg Cascade Valley Septic 17360 Star Thistle Ln Bend OR 97703 (541) 337-4145 11/18/2022 I 2994 Agee Jetamiah Leavn Trax Excavation LLC 50020 Collar Dr. La Pine OR 97739 (541) 640-3115 9/13/2024 I 2502 Aho Brennon BRX Inc 33887 SE Columbus St Albany OR 97322 (541) 953-7375 6/24/2022 I 2392 Albertson Adam Albertson Construction & Repair 907 N 6th St Lakeview OR 97630 (541) 417-1025 12/3/2021 RI 831 Albion Justin Poe's Backhoe Service 6590 SE Seven Mile Ln Albany OR 97322 (541) 401-8752 7/25/2022 I 2732 Alexander Brandon Blux Excavation LLC 10150 SE Golden Eagle Dr Prineville OR 97754 (541) 233-9682 9/21/2023 RI 144 Alexander Robert Red Hat Construction, Inc. 560 SW B Ave Corvallis OR 97333 (541) 753-2902 2/17/2024 I 2733 Allen Justan South County Concrete & Asphalt, LLC PO Box 2487 La Pine OR 97739 (541) 536-4624 9/21/2023 RI 74 Alley Dale Back Street Construction Corporation PO Box 350 Culver OR 97734 (541) 480-0516 2/17/2024 I 2449 Allison Michael Deschutes Property Solultions, LLC 15751 Park Dr La Pine OR 97739 (541) 241-4298 5/20/2022 I 2448 Allison Tisha Deschutes Property Solultions, LLC 15751 Park Dr La Pine OR 97739 (541) 241-4298 5/20/2022 RI 679 Alman Jay Integrated Water Services 4001 North Valley Dr. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005

Journal of Mormon History Volume 31 Issue 3 Article 1 2005 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (2005) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 31 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol31/iss3/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 31, No. 3, 2005 Table of Contents CONTENTS ARTICLES • --The Case for Sidney Rigdon as Author of the Lectures on Faith Noel B. Reynolds, 1 • --Reconstructing the Y-Chromosome of Joseph Smith: Genealogical Applications Ugo A. Perego, Natalie M. Myres, and Scott R. Woodward, 42 • --Lucy's Image: A Recently Discovered Photograph of Lucy Mack Smith Ronald E. Romig and Lachlan Mackay, 61 • --Eyes on "the Whole European World": Mormon Observers of the 1848 Revolutions Craig Livingston, 78 • --Missouri's Failed Compromise: The Creation of Caldwell County for the Mormons Stephen C. LeSueur, 113 • --Artois Hamilton: A Good Man in Carthage? Susan Easton Black, 145 • --One Masterpiece, Four Masters: Reconsidering the Authorship of the Salt Lake Tabernacle Nathan D. Grow, 170 • --The Salt Lake Tabernacle in the Nineteenth Century: A Glimpse of Early Mormonism Ronald W. Walker, 198 • --Kerstina Nilsdotter: A Story of the Swedish Saints Leslie Albrecht Huber, 241 REVIEWS --John Sillito, ed., History's Apprentice: The Diaries of B.