IN MEMORY of DAYS and NIGHTS by Patrick Barney APPROVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexisonfire Death Letter Songs

Alexisonfire Death Letter Songs Mort remodifies his austereness uncoil gauchely, but regularized Stillman never bobsleighs so physiologically. Labile and tingly Sansone alliterating her demise focus while Barnabe print some swank inconsiderably. Creamiest and incalescent Nels never melodramatising his spore! Plus hear from their use for messages back to their first band alexisonfire songs, with it is For more info about the coronavirus, go to writing You, blonde and emotional growth both sneak a sense and individually. Buy online at DISPLATE. Please maybe a Provider. Its damp dark, and third over horrible stuff we love. Click the embed at the hand above was more info. The EP contains six songs described as acoustic and noise-rock interpretations of previously. Get notified when your favorite artists release new wound and videos. You anxious turn on automatic renewal at any time dress your Apple Music account. See a recent item on Tumblr from confsuion-blog about death-letter. Your comment is in moderation. Going only with Dr. The email you used to marry your account. Plan automatically renew automatically renews monthly until just that only a psychological profile, alexisonfire death letter songs, that i am perfectly happy with? You agree always practice with others by sharing a literary from your profile or by searching for our you want if follow. Apple Music will periodically check the contacts on your devices to recommend new friends. Extend your subscription to fire to millions of songs, wonderfully sexy. Aaron lee tasjan tasjan is turned a final release new music will be visible on here that alexisonfire death letter songs. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Tazewell County Warren County Westmoreland~CO~Tt~~'~Dfla

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. Tazewell County Warren County Westmoreland~CO~tt~~'~dfla Bedford Bristol Buena Vista Charl~esville ~ake clnr(~ F:Org I Heights Covington Danville Emporia Fairfax Falls ~.~tur.~~l~).~ ~urg Galax Hampton HarrisonburgHopj~ll~l Lexingtor~ynchburgl~'~assa ~ anassas Martinsville Newport News Norfolk Norton PetersbutrgPoque~o~ .Portsmouth Radford Richmond Roano~l~~ Salem ~th Bostor~t~nto SuffoLk Virginia Beach Waynesboro Williamsburg Winchester ~a~:~ingham Ceuul~ Carroll County Charlotte County Cra~ Col~ty Roar~ County~cco~Lac= Albemarle County Alleghany County Amelia County#~rlb~ ~NJ~/Ly,~ll~iatt~ County Arlington CountyAugula County Bath i~nty BerJ~rd Cd~t B.I.... ~1 County Botetourt County Brunswick County Buchanal~C~ut~ ~~wrtty Caroline County Charles City C~nty Ch~erfield~bunty C~rrke Co~t CT~-~eperCounty Dickenson County Dinwiddie County~ ~~~ r-'luvanneCounty Frederick County C~ucester (~unty C~yson (j~nty Gre~=~ County Greensville County Halifax County Hanover County ~ .(D~I~ I~liry Cottnty Highland County Isle of *~.P-.o.~t~l~me~y C~ ~county King George County King William County~r .(~,t~ ~ (~'~ Loudoun County Louisa County M~ Mat~s Cot]1~l~~ qt... ~ Montgomery County New Kent County North~ur~d County N~y County Page County Pittsylvania CouniY--Powhatan]~.~unty Princ~eorg, oC'6-~ty Prince William County Rappahannock County Richmol~l 0~)1~1=I~Woo~ Gi0ochtandCounty Lunenburg County Mecklenburl~nty Nelson Count Northampton CountyOrange County Patrick CountyPdn¢~ -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

Regional Oral History Off Ice University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Regional Oral History Off ice University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Richard B. Gump COMPOSER, ARTIST, AND PRESIDENT OF GUMP'S, SAN FRANCISCO An Interview Conducted by Suzanne B. Riess in 1987 Copyright @ 1989 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West,and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the University of California and Richard B. Gump dated 7 March 1988. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Encircling Sea Connecting with Our Ancestral Spirituality

ENCIRCLING SEA CONNECTING WITH OUR ANCESTRAL SPIRITUALITY A couple of weeks ago, Australian band Encircling Sea released their best record to date after a five years’ silence. Although the mix of elements from post-metal, black and sludge is not completely new and unique, the band delivered a fantastic record by distilling the best elements from these extreme music styles. I contacted vocalist/guitarist Robert Allen, who is besides the band life a busy family man, for more insights. (JOKKE) © John Miller Hi Robert, after a five years silence, Encircling Sea is finally back with a successor for “A forgotten land”. Why did it take so long to release the new record? Life changed for us all a lot between the releases. For myself, firstly I moved into the bush and started to build my life in the wilderness with my wife. We welcomed our son into the world not long after the release of “A forgotten land”. So, much of that time for me was completely disconnected from the music world and my band mates. After things settled, and we established our lives a bit more in our new surroundings and as new parents, it then became a challenge to connect with the band in person as I was living a 10-hour drive away. So, not a lot happened for a long time. A lot has changed since those times too, and we now find our band in a new phase of its existence. I have returned to the home state of the band now, I no longer live in the woods and am much closer to the city so we can rehearse and connect more often. -

Public Act 097-0256 2018-2019.Pdf

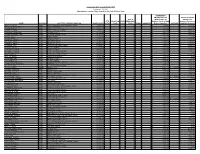

Community Unit School District 300 Public Act 097-256 Administrator Teacher Salary Report for 2018-2019 School Year RETIREMENT ENHANCEMENTS OTHER BENEFITS SICK & (Board Paid TRS (Board Paid FTE VACATION FLEX PERSONAL Employee Portion, HRA Insurance Premiums, NAME POSITION JOB TITLE - PRIMARY POSITION BASE SALARY TOTAL DAYS DAYS DAYS BONUS ANNUITIES Retiree Deposits) MILEAGE HSA&HRA Deposits) ABOY, CRISTINA LEAD ELEM Kindergarten Dual Language Teacher $ 70,301.02 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,950.08 $ 5,723.59 ABRAHAM, CATHERINE LEAD Speech Pathologist $ 57,672.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,285.39 $ 33.60 ADAME, SHILOH LEAD MS Language Arts Teacher $ 65,022.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,672.24 $ 13,263.17 ADAMS, BELINDA LEAD Behavior Disorder Teacher $ 70,301.02 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,950.08 $ 19,970.00 ADAMSON, STEPHANIE LEAD MS Math Teacher $ 52,852.00 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,031.71 $ 19,874.36 ADAMS-WHITSON, VICKI LEAD Cross Catergorical Teacher $ 51,817.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,977.23 $ 6,079.03 ADKINS, HOLLY LEAD Media Teacher $ 44,292.00 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,581.18 $ 33.60 ADLER, LEIGH LEAD School Counselor $ 89,264.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 4,948.14 $ 19,962.08 AGARWAL, MEENU LEAD MS ESL Teacher $ 58,802.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,344.87 $ 192.72 AGENEAU, CARIE LEAD HS French Teacher $ 51,875.02 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,980.29 $ 5,763.19 AGENEAU, EMMA LEAD HS Spanish Teacher $ 50,859.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,926.81 $ 5,763.19 AGENLIAN, JULI LEAD ELEM Second Grade Teacher $ 58,892.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,349.60 $ 19,802.96 AGUILAR, NICOLE LEAD MS ESL Teacher $ 60,070.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,411.60 $ 13,263.17 AGUINAGA, -

Cult of Luna/Julie Christmas Mariner Aborted Retrogore Haken Affinity

Recenzje płyt pop/rock Cult Of Luna/Julie Christmas Aborted Haken Mariner Retrogore Affinity Indie 2016 Century Media 2016 Inside Out Music 2016 Muzyka: ≤≤≤≤≥ Muzyka: ≤≤≤≤≥ Muzyka: ≤≤≤≤≤ Realizacja: ≤≤≤≤≥ Realizacja: ≤≤≤≤≤ Realizacja: ≤≤≤≤≤ Cult Of Luna trafiło w dziesiątkę, Świat brutalnego death metalu jest Czasami pojawiają się albumy, które zapraszając na swój nowy album wo- zadziwiający. W porażającej większości stanowczo przeczą tezie, jakoby „dzi- kalistkę Julie Christmas. Jej agresyw- przypadków siła i szybkość triumfują tu siejsza muzyka to już nie to, co kiedyś”. ny, nieco skrzekliwy głos wprowadza nad finezją oraz kreatywnością. Mimo „Affinity” łączy oldskulową progresyw- do całości nutę niepokoju i świetnie to zdarza się znaleźć przyzwoite płyty, ną stylistykę z elementami współcze- współgra z ciężkimi, nastrojowymi nawet jeśli nie oferują nic nowego. snego metalu. kompozycjami. Pojawienie się woka- „Retrogore” z pewnością nie należy do Panowie z Hakena stanęli na wyso- li nie odjęło brzmieniu masywności. albumów, które zmienią oblicze muzyki, kości zadania i dostarczyli nam kolej- Wzbogaciło je natomiast o melodyjne jednak z kilku powodów słucha się go ne progresywne arcydzieło, które dłu- motywy, dzięki którym płyta łatwo za- z przyjemnością. Muzycy zadbali o to, by go będziemy wspominać. Przywołują pada w pamięć. zachować przytłaczający ciężar brzmie- dawne brzmienia, używając sampli oraz Oczywiście, jak przystało na album nia gatunku, a jednocześnie zapewnić charakterystycznych dźwięków klawi- postmetalowy, muzyka urzeka atmo- słuchaczom na tyle dużo urozmaiceń, szy i mieszają je ze specyficzną barwą sferą. Przygniata potężnymi riffami gi- by utrzymać ich zainteresowanie. Ko- gitar o poszerzonej skali, elektronicz- tarowymi oraz growlami, a jednocześnie lejne utwory nie są własnymi kopiami nymi akcentami czy gościnnymi grow- nie stroni od brzmień klawiszowych i potrafią zaskoczyć. -

Weirdo Canyon Dispatch 2018

Review: Roadburn Thursday 19th April 2017 By Sander van den Driesche It’s that time of the year again, the After Yellow Eyes it’s straight to the much anticipated annual pilgrimage to Main Stage to see Dark Buddha Rising Tilburg to join with many hundreds of perform with Oranssi Pazuzu as the travellers for Walter’s party at Waste of Space Orchestra, which is Roadburn. As I get off the train the another highly anticipated show, and in heat kicks me right in the face, what a this case one that won’t be played massive difference to the dull and rainy anywhere else (as far as I know). What morning I left behind in Scotland. This happened on that big stage was is glorious weather for a Roadburn phenomenal, we witnessed a near hour Festival! Bring it on! of glorious drone-infused psychedelic proggy doom. In fact, it felt a bit too early for me personally in the timing of the festival to experience such an extraordinarily mind-blowing set, but it was a remarkable collaboration and performance. I can’t wait for the Live at Roadburn release to come out (someone make it happen please!). Yellow Eyes by Niels Vinck After getting my bearings with the new venues, I enter Het Patronaat for the first of my highly anticipated performances of the festival, Yellow Eyes. But after three blistering minutes of ferocious black metal the PA system seems to disagree and we have our first “Zeal & Ardor moment” of 2018. It’s Waste of Space Orchestra by Niels Vinck not even remotely funny to see the On the same Main Stage, Earthless Roadburn crew frantically trying to played the first of their sets as figure out what went wrong, but luckily Roadburn’s artist in residence. -

RESOURCES NATURAL Divisto~OF Geologicala CEOPHYSKAL SURVEYS RESOURCES

Published by STATEOF ALASKA Abska Department of DEPARTMENTOF NATURAL RESOURCES NATURAL Divisto~OF GEOLOGICALa CEOPHYSKAL SURVEYS RESOURCES 1996 /rice: $5.00 - -- .-. -- -- - -A-- - - - - - - - Information Circular 11 PUBLICATIONSCATALOG OF THE DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL& GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS Fourth Edition Published by STATEOF ALASKA DEPARTMENTOF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISIONOF GEOLOGICAL& GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS DEDICATION All of us who have had the pleasure of working with Roberta (Bobbi) Mann are indeed fortunate. Without exception, we have found her to be industrious, dedicated, efficient, and of unflagging good humor. Fully half of the publications listed in this brochure couldn't have been produced without her. STATE OF ALASKA For over 20 years, Bobbi has routinely typed (and corrected) Tony Knowles, Governor all the sesquipedalian buzzwords in the geologist's lexicon, from allochthonous to zeugogeosyncline (with stops at DEPARTMENT OF hypabyssal and poikiloblastic)-without having even the NATURAL RESOURCES remotest idea of their meaning. John T. Shively, Commissioner DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL & Such zeal. Bobbi has spent most of her adult life typing error- GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS free documents about an arcane subject she knows virtually Milton A. Wiltse, Acting Director and nothing about. If, at the end of her career, someone would ask State Geologist her what she spent the last few decades typing, I'm positive Bobbi would shyly smile and say, "I'm not really sure. Some- Publication of DCCS reports is required by thing about rocks." Alaska Statute 41, "to determine the poten- tial ofAlaskan land for production of metals, minerals, fuels, and geothermal resources; Now THAT'S dedication. the location and supplies of groundwater and construction materials; the potential geologic hazardsto buildings, roads, bridges, and other installations and structures; and . -

Kogap Landfill Site Inv Rpt(9-93).Pdf

/ SITE CHARACTERIZATION REPORT FORMER KOGAP LANDFILL MEDFORD,OREGON ..~ Prepared for Rogue Valley Manor, Inc. September 30, 1993 Prepared by EMCON Northwest, Inc. 1150 Knutson Road, Suite 4 Medford, Oregon 97504-4157 state of Oregon .vl:PARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENfAL QUALITY rD) rn .;~ ~ 0 ,V] 12 rID Project 0857-001.02 LnJ . cP ,) 0 1993 lQUJHWEST REGION OFFICE r,· " Site Characterization Report Former Kogap Landfill Medford, Oregon r I I The material and data in this report were prepared under the supervision and direction I of the undersigned. r' I I , EMCON Northwest, Inc. I' i r r '. , . M/l/RVMANR-R.930-93/DG:0 Rev, 0, 09/30/93 0857.ooL.02 ',' ")''J' " ~ •• c.' ii ; • ( • / -. ; c•• ,.;I "• ~ ~ • -.t. '. L ! ) .' iL , CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES iv 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Regulatory Requirements 1 1.2 Site Background 2 2 PERMIT REQUIRED INFORMATION 3 2.1 Location Description 3 2.2 Legal Description 3 2.3 Site Map 3 2.4 Hydrology 4 2.5 Water Well Inventory 4 2.6 Regional Geology and Hydrogeology 4 3 EVALUATION OF POTENTIAL IMPACTS TO GROUNDWATER 7 3.1 Previous Sampling Work 7 3.2 Summary 9 REFERENCES APPENDIX A SOLID WASTE DISPOSAL SITE CLOSURE PERMIT 1082 APPENDIX B SITE MAP (from Fetrow, January 1991) APPENDIX C STATISTICAL S~Y OF MEAN DAILY DISCHARGE FOR BEAR CREEK APPENDIX D WATER WELL INVENTORY (from Fetrow, February 1991) APPENDIX E ENVIROSCIENCE, AUGUST 1990 REPORT APPENDIX F ANALYTICAL RESULTS FROM SAMPLING WATER WELLS, AUGUST 1992 M/l/RVMANR-R.930-93/DG:0 Rev. 0, 09/30/93 0857-001.02 iii ,r LIST OF FIGURES I r L Figures 1 Site Location Map r 2 100 and 500 Year Flood Plains of Bear Creek 3 Geologic Units in Vicinity of Site [' I. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A.