The Development of Civil Society in Central Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Failed Democratic Experience in Kyrgyzstan: 1990-2000 a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle Ea

FAILED DEMOCRATIC EXPERIENCE IN KYRGYZSTAN: 1990-2000 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY OURAN NIAZALIEV IN THE PARTIAL FULLFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION APRIL 2004 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences __________________________ Prof. Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for degree of Master of Science __________________________ Prof. Dr. Feride Acar Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. __________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Pınar Akçalı Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assist. Prof. Dr. Pınar Akcalı __________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Canan Aslan __________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Oktay F. Tanrısever __________________________ ABSTRACT FAILED DEMOCRATIC EXPERIENCE IN KYRGYZSTAN: 1990-2000 Niazaliev, Ouran M.Sc., Department of Political Science and Public Administration Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Pınar Akçalı April 2004, 158 p. This study seeks to analyze the process of transition and democratization in Kyrgyzstan from 1990 to 2000. The collapse of the Soviet Union opened new political perspectives for Kyrgyzstan and a chance to develop sovereign state based on democratic principles and values. Initially Kyrgyzstan attained some progress in building up a democratic state. However, in the second half of 1990s Kyrgyzstan shifted toward authoritarianism. Therefore, the full-scale transition to democracy has not been realized, and a well-functioning democracy has not been established. -

2012 Annual Report

U.S. Commission on InternationalUSCIRF Religious Freedom Annual Report 2012 Front Cover: Nearly 3,000 Egyptian mourners gather in central Cairo on October 13, 2011 in honor of Coptic Christians among 25 people killed in clashes during a demonstration over an attack on a church. MAHMUD HAMS/AFP/Getty Images Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom March 2012 (Covering April 1, 2011 – February 29, 2012) Commissioners Leonard A. Leo Chair Dr. Don Argue Dr. Elizabeth H. Prodromou Vice Chairs Felice D. Gaer Dr. Azizah al-Hibri Dr. Richard D. Land Dr. William J. Shaw Nina Shea Ted Van Der Meid Ambassador Suzan D. Johnson Cook, ex officio, non-voting member Ambassador Jackie Wolcott Executive Director Professional Staff David Dettoni, Director of Operations and Outreach Judith E. Golub, Director of Government Relations Paul Liben, Executive Writer John G. Malcolm, General Counsel Knox Thames, Director of Policy and Research Dwight Bashir, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Scott Flipse, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Sahar Chaudhry, Policy Analyst Catherine Cosman, Senior Policy Analyst Deborah DuCre, Receptionist Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Jacqueline A. Mitchell, Executive Coordinator U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom 800 North Capitol Street, NW, Suite 790 Washington, DC 20002 202-523-3240, 202-523-5020 (fax) www.uscirf.gov Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom March 2012 (Covering April 1, 2011 – February 29, 2012) Table of Contents Overview of Findings and Recommendations……………………………………………..1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..1 Countries of Particular Concern and the Watch List…………………………………2 Overview of CPC Recommendations and Watch List……………………………….6 Prisoners……………………………………………………………………………..12 USCIRF’s Role in IRFA Implementation…………………………………………………14 Selected Accomplishments…………………………………………………………..15 Engaging the U.S. -

Chapter 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Naken K. Kasiev 1.1 Geography, Population, and Culture The Kyrgyz Republic is located in the center of Central Asia and shares borders with Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and China. The Kyrgyz Republic is primarily mountainous with dry fertile valleys and deep gorges. The two main areas which are the base of Kyrgyz agriculture are the Ferghana Valley, in the Southwest, and the Chu Valley, in the North. Lake Issyk-Kul, located in Northeast Kyrgyzstan, is the second deepest mountain lake in the world. It is the main tourist and recreational spot in the country. The population of the Kyrgyz Republic is more than 4.5 million. The country has an ethnically diverse population. According to the National Statistical Committee, in 1997 the ethnic breakdown was as follows: 61 percent Kyrgyz, 15 percent Russian, 14 percent Uzbek, and 10 percent a mix of Ukrainian, German, Kazakh, Tatar, Dungan, Tajik, Uigur, Korean, and others. Thirty-four percent of the population lives in urban areas, 66 percent in rural areas (National Statistical Committee, 1997). The national language is Kyrgyz, which belongs to the Turkic language group. Russian is widely spoken and is an important language of communication. The primary religion of the people of the Kyrgyz Republic is Sunni Islam. There are many ancient and modern cultural values in the Kyrgyz Republic. The great epic “Manas” characterizes the Kyrgyz people’s independence and courage, and glorifies the legendary nobleman Manas. It is one of the longest epics in world literature (longer than the Iliad and the Odyssey combined), and is passed on orally from generation to generation. -

COVID-19 Central Asia Infographic Series

COVID-19 in Central Asia: Infographic Series KAZAKHSTAN Kazakhstan first announced a state of emergency and imposed a nationwide lockdown from March 16 to May 11. As cases started to climb after the lockdown lifted, and new data collection methods pointed to more 78,486 49,488 585 infections in the country than previously counted, the Total Confirmed Recovered Deaths government announced a second nationwide lockdown COVID-19 Cases from July 5 to August 2. Kazakhstan has the highest Source: JHU number of COVID-19 infections relative to population size in Central Asia. Nur-Sultan (formerly Astana) Atyrau Tengiz Oil Field Almaty IMPACT TO THE PRIVATE SECTOR COVID-19 is the biggest shock to Kazakhstan's economy in two decades, and has had a negative impact on economic growth. The economy is heavily reliant on foreign investment through ongoing oil, gas, and infrastructure projects. The Tengiz Oil Field in the Atyrau region has reported upwards of 2,000 cases of COVID-19 among 36 shift camps and 57 companies operating in the field. Chevron-led Tengizchevroil owns the site, and has temporarily paused non-essential work activities in an attempt to slow the spread of cases. Entry restrictions may affect the movement of migrant workers staffing the project site. The capital, Nur-Sultan, and Kazakhstan's financial hub, Almaty, have led the count in confirmed cases of COVID-19. Hospitals in both major cities are reportedly nearing full capacity, and may be unavailable to new patients. In Nur-Sultan, the Presidential Hospital and City Hospital #2 recently resumed some level of surgical and other services, opening up access to acute trauma care. -

Investor's Atlas 2006

INVESTOR’S ATLAS 2006 Investor’s ATLAS Contents Akmola Region ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Aktobe Region .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 Almaty Region ............................................................................................................................................................ 12 Atyrau Region .............................................................................................................................................................. 17 Eastern Kazakhstan Region............................................................................................................................................. 20 Karaganda Region ........................................................................................................................................................ 24 Kostanai Region ........................................................................................................................................................... 28 Kyzylorda Region .......................................................................................................................................................... 31 Mangistau Region ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Country Codes and Currency Codes in Research Datasets Technical Report 2020-01

Country codes and currency codes in research datasets Technical Report 2020-01 Technical Report: version 1 Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre Harald Stahl Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 2 Abstract We describe the country and currency codes provided in research datasets. Keywords: country, currency, iso-3166, iso-4217 Technical Report: version 1 DOI: 10.12757/BBk.CountryCodes.01.01 Citation: Stahl, H. (2020). Country codes and currency codes in research datasets: Technical Report 2020-01 – Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre. 3 Contents Special cases ......................................... 4 1 Appendix: Alpha code .................................. 6 1.1 Countries sorted by code . 6 1.2 Countries sorted by description . 11 1.3 Currencies sorted by code . 17 1.4 Currencies sorted by descriptio . 23 2 Appendix: previous numeric code ............................ 30 2.1 Countries numeric by code . 30 2.2 Countries by description . 35 Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 4 Special cases From 2020 on research datasets shall provide ISO-3166 two-letter code. However, there are addi- tional codes beginning with ‘X’ that are requested by the European Commission for some statistics and the breakdown of countries may vary between datasets. For bank related data it is import- ant to have separate data for Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man, whereas researchers of the real economy have an interest in small territories like Ceuta and Melilla that are not always covered by ISO-3166. Countries that are treated differently in different statistics are described below. These are – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – France – Spain – Former Yugoslavia – Serbia United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

Progress Report on the Implementation of the Grant ECE/GC/2017/11/025 “Improved Understanding of Key Water Management Issues by Mid-Level Government Officials”

Progress Report on the implementation of the grant ECE/GC/2017/11/025 “Improved understanding of key water management issues by mid-level government officials” . Kazakh-German University 1 January – 31th of July, 2018 1 part (Aktau training) Narrative report prepared by the German-Kazakh University 1. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT Within the framework of the project 025 “Improved understanding of key water management issues by mid-level government officials”, German-Kazakh University was responsible to implement the following tasks under the grant ECE/GC/2017/11/025: • Organization of training for civil servants on Integrated Water Resources Management in collaboration with the State Academy of Management under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan (State Academy) Aktau, Kazakhstan – April 9 – 11/2018 • Organization of training for civil servants on Integrated Water Resources Management in collaboration with the State Academy of Management under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan (State Academy) Almaty, Kazakhstan – May 28 – 30/2018 Below is the description of activities implemented under each of the above tasks. Task I: Organization of IWRM training for civil servants in Aktau Based on the previous grant ECE/GC/2017.07.013 the second training for government officials was organized in Mangystay region (Aktau city) in order to cover water professionals from the Southwest region of the Republic of Kazakhstan. The training was organized by the Kazakh-German University with the support of the UNECE and in partnership with the RK State Academy Mangystay branch. The training was organized for 30 participants including trainers and organizational staff. The target audience of the training was the mid-level government staff. -

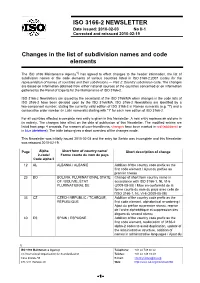

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date issued: 2010-02-03 No II-1 Corrected and reissued 2010-02-19 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (e.g. "I") and a consecutive order number (in Latin numerals) starting with "1" for each new edition of ISO 3166-2. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. For reasons of user-friendliness, changes have been marked in red (additions) or in blue (deletions). The table below gives a short overview of the changes made. This Newsletter was initially issued 2010-02-03 and the entry for Serbia was incomplete and this Newsletter was reissued 2010-02-19. -

Commercial Banks of Uzbekistan

Commercial banks of Uzbekistan August 10, 2005 JETRO Tashkent office Copyright 2005 JETRO Content Part 1 Overview of Banking System ........................................................................................................................... 3 Total table: Business information...................................................................................................................... 4 Total table: Staff information............................................................................................................................ 8 Total table: Service charges .............................................................................................................................10 Total table: Owners .........................................................................................................................................12 Total table: Clients ..........................................................................................................................................15 Part 2 1. National Bank for Foreign Economic Activity of Uzbekistan .......................................................................18 2. State Joint-Stock Commercial bank "ASAKA Bank"....................................................................................22 3. State Commercial "Uzbekiston Respublikasi Xalq banki".............................................................................24 4. UzDaewoo bank ..........................................................................................................................................26 -

Christopher Aaron Baker

Skills Languages: advanced proficiency in reading and speaking Kazakh proficiency; reading knowledge of Azeri, Uzbek, Turkmen and Persian; reading knowledge of Russian with basic speaking proficiency. Education Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana Ph.D. in Central Asia, with a minor field in Russian History, expected completion, 2014 Coursework and Comprehensive Examinations Completed, 2009 M.A. in Central Eurasian studies, 2006 University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada ABD in European Intellectual History, with minor fields in Cultural Theory and Contemporary European History, 1999 University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada M.A. in European History, 1993 University of California at Davis, Davis, California B.A. in European History (magna cum laude), 1992 Professional Appointments Assistant Professor, American University of Central Asia, Bishkek, August 2013-present Research Coordinator, Central Asian Studies Institute, American University of Central Asia, August 2013-present: Honors and Awards Summer Research Lab Fellowship, University of Illinois, 2012 AAS/SSRC Dissertation Workshop Fellowship, 2012 Nazarbayev University grant for Kazakh-English dictionary, 2012 U.S. Embassy grant for Kazakh-English dictionary, 2011 Fulbright Hays Dissertation Award for dissertation research in Kazakhstan, 2010 IREX Individual Advanced Research Opportunities Grant for dissertation research in Kazakhstan, 2007-2008 Title VI FLAS for Azeri, summer 2007 Title VI FLAS for Advanced Directed Language Study in Kazakh, 2006-2007 SSRC Grant for Azeri, summer 2006 -

Delivery Destinations

Delivery Destinations 50 - 2,000 kg 2,001 - 3,000 kg 3,001 - 10,000 kg 10,000 - 24,000 kg over 24,000 kg (vol. 1 - 12 m3) (vol. 12 - 16 m3) (vol. 16 - 33 m3) (vol. 33 - 82 m3) (vol. 83 m3 and above) District Province/States Andijan region Andijan district Andijan region Asaka district Andijan region Balikchi district Andijan region Bulokboshi district Andijan region Buz district Andijan region Djalakuduk district Andijan region Izoboksan district Andijan region Korasuv city Andijan region Markhamat district Andijan region Oltinkul district Andijan region Pakhtaobod district Andijan region Khdjaobod district Andijan region Ulugnor district Andijan region Shakhrikhon district Andijan region Kurgontepa district Andijan region Andijan City Andijan region Khanabad City Bukhara region Bukhara district Bukhara region Vobkent district Bukhara region Jandar district Bukhara region Kagan district Bukhara region Olot district Bukhara region Peshkul district Bukhara region Romitan district Bukhara region Shofirkhon district Bukhara region Qoraqul district Bukhara region Gijduvan district Bukhara region Qoravul bazar district Bukhara region Kagan City Bukhara region Bukhara City Jizzakh region Arnasoy district Jizzakh region Bakhmal district Jizzakh region Galloaral district Jizzakh region Sh. Rashidov district Jizzakh region Dostlik district Jizzakh region Zomin district Jizzakh region Mirzachul district Jizzakh region Zafarabad district Jizzakh region Pakhtakor district Jizzakh region Forish district Jizzakh region Yangiabad district Jizzakh region -

Russian Minorities in the Post-Soviet Space: a Comparative Analysis of Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan

Russian minorities in the Post-Soviet Space: a Comparative analysis of Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan By Zhyldyz Abaskanova Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts CEU eTD Collection Supervisor: Associate Professor Thomas Fetzer Word count: 13, 428 Budapest, Hungary 2016 i Abstract Under the Soviet Union, Russians were spread out over the entire territory of the USSR. Russians held high positions in the Soviet Union. However, after the disintegration of the USSR, Russians who lived outside of Russia acquired the new status of being a minority. The sudden collapse of the USSR raised many concerns and fears for Russians who lived outside of Russia, since successor states prioritized nation-building processes. This study examines the treatment of Russian memories in Uzbekistan and in Kyrgyzstan by using Rogers Brubaker’s framework of triadic nexus. The research covers the relations between national minority with nationalizing state and relation of national minority with external national homelands. Primarily, this thesis considers Uzbekistan’s and Kyrgyzstan’s treatment of Russians minorities on the basis of language and access to politics. There are examined nationalizing policies of Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan and Russian minorities’ opinion toward such policies. In addition, it provides an analysis of Russian Federation policies on supporting its compatriots in foreign countries and Russian minorities’ assessment of Russia as a state that support and pursue their interest. Based on qualitative and quantitative data, I claim that the treatments of Russians in both states are different in terms of language policies and politics.