2003Session3.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characteristics of Grapevine Yellows-Susceptible Vineyards and Potential Management Strategies

YEAR-END PROJECT REPORT Virginia Wine Board, August, 2015 Title: Characteristics of Grapevine Yellows-susceptible vineyards and potential management strategies Principal Investigators: Dr. Paolo Lenzi (100% time on project) Dr. Tony K. Wolf (10% time on project) Postdoctoral Research Associate Professor of Viticulture AHS Jr. AREC, Virginia Tech AHS Jr. AREC Virginia Tech Virginia Tech Phone: (540) 869-2560 extn 42 (540) 869-2560 extn 18 [email protected] [email protected] Type of Project: Research Amount funded: $110,903 Overall Project Objectives 1. Identify phytoplasma alternative hosts in and around North American Grapevine Yellows (NAGY)- affected vineyards and attempt to identify the characteristics of vineyards that predispose them to increased risk of NAGY 2. Evaluate efficacy of potential Grapevine Yellows management practices Summary North American Grapevine Yellows (NAGY) was recognized in Virginia vineyards as early as 1987. Principal investigator T. Wolf began a collaborative research association with Dr. Robert Davis and his lab at the USDA/ARS in Beltsville Maryland and that partnership led to a greater understanding of the nature of the pathogens that cause NAGY in Virginia. An important finding from our work of the nineties was that the causal agents of NAGY – bacteria-like organisms called phytoplasmas – were unique to grapevine yellows diseases in North America. That is, they were not the same pathogens that cause the European variants of the disease, such as Flavescence dorée , or Bois noir . The missing information about NAGY was which vector or vectors were involved in phytoplasma transmission, and what other plants in the vineyard environment served as alternative hosts for the pathogens. -

IPM Elements for Wine Grapes in Virginia and North Carolina

IPM Elements for Wine Grapes in Virginia and North Carolina Growers should use this document and its sub-headings as a checklist of possible Integrated Pest Management (IPM) practices that they could implement. Growers should count only the activities they perform in their wine grape pest management practices and aim to be compliant with at least 80% of the activities listed. This is not a requirement, but only a suggested level of compliance. This document is intended to help wine grape growers identify areas in their operations that possess strong IPM qualities and also point out areas for improvement. Growers should attempt to incorporate the majority of these specific techniques into their usual production and maintenance practices, especially in areas where they fall short of the 80% goal. Pests and Diseases of Wine Grapes in Virginia and North Carolina Arthropods Diseases Vertebrates Weeds Aerial phylloxera Anthracnose Bears Annual broadleaf Climbing cutworms Bitter Rot Birds weeds European red mite Black rot Deer Annual grasses Grape berry moth Botryosphaeria canker Geese Perennial grasses Grape cane borer Botrytis bunch rot Groundhogs Perennial broadleaf Grape cane gallmaker Crown gall Moles weeds, including Grape cane girdler Downy mildew Raccoons Woody perennials Grape curculio ESCA or Petri Turkeys Yellow nutsedge Grape flea beetle diseases Voles Grape leafhopper (Young vine decline) Grape root borer Eutypa dieback Grape rootworm Grapevine yellows Grape tumid Leafroll virus gallmaker Phomopsis cane and Grapevine looper leaf spot Japanese beetle Pierce’s disease Mealybugs Powdery mildew Redbanded leafroller Ripe rot Sharpshooters Sour rot (non-specific Stinkbugs fruit rot) Wasps Tomato/Tobacco ringspot virus Check if done I. -

Final Grape Draft 0814

DETECTION AND DIAGNOSIS OF RED LEAF DISEASES OF GRAPES (VITIS SPP) IN OKLAHOMA By SARA ELIZABETH WALLACE Bachelor of Science in Horticulture Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2016 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE July, 2018 DETECTION AND DIAGNOSIS OF RED LEAF DISEASES OF GRAPES (VITIS SPP) IN OKLAHOMA Thesis Approved: Dr. Francisco Ochoa-Corona Thesis Adviser Dr. Eric Rebek Dr. Hassan Melouk ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to Francisco Ochoa-Corona, for adopting me into his VirusChasers family, I have learned a lot, but more importantly, gained friends for life. Thank you for embracing my horticulture knowledge and allowing me to share plant and field experience. Thank you to Jen Olson for listening and offering me this project. It was great to work with you and Jana Slaughter in the PDIDL. Without your help and direction, I would not have achieved this degree. Thank you for your time and assistance with the multiple drafts. Thank you to Dr. Rebek and Dr. Melouk for being on my committee, for your advice, and thinking outside the box for this project. I would like to thank Dr. Astri Wayadande and Dr. Carla Garzon for the initial opportunity as a National Needs Fellow and for becoming part of the NIMFFAB family. I have gained a vast knowledge about biosecurity and an international awareness with guests, international scientists, and thanks to Dr. Kitty Cardwell, an internship with USDA APHIS. Thank you to Gaby Oquera-Tornkein who listened to a struggling student and pointed me in the right direction. -

Original Paper

Copyright © 2019 University of Bucharest Rom Biotechnol Lett. 2019; 24(6): 1027-1033 Printed in Romania. All rights reserved doi: 10.25083/rbl/24.6/1027.1033 ISSN print: 1224-5984 ISSN online: 2248-3942 Received for publication, Janaury, 7, 2018 Accepted, October, 5, 2018 Original paper Organic acids and sugars profile of some grape cultivars affected by grapevine yellows symptoms CRISTINA PETRISOR1*, CONSTANTINA CHIRECEANU1 1Research and Development Institute for Plant Protection, Ion Ionescu de la Brad Bdv, No. 8, District 1, Bucharest, Romania Abstract Grapevine yellows are a group of infectious diseases, which are usually associated with phytoplasma pathogens, affecting quality of grapes and survival of grapevine. The objective of this work was to evaluate sugars, total phenols and organic acids concentrations in the grapes of four wine cultivars (Fetească Neagră, Pinot Noir, Traminer rose, Chardonnay) healthy and affected by specific symptoms to phytoplasmoses. Berry samples were collected from the Miniș-Măderat (Arad County) and Odobești (Vrancea County) vineyards. Individual sugars and organic acids compounds were identified and quantified in grape berries by the high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method using DAD and RID detectors, while total phenolic compounds by using spectrophotometry. The content and composition of sugars and acids varied between healthy and symptomatic plants. Analysis of grape juice revealed reduction in sugars (fructose and glucose) from symptomatic to non-symptomatic vines. Lower values of acidity were obtained in grapes of affected compared to non-affected vines. The differences in acids content between grapes of affected and not affected vines were more pronounced at Pinot Noir variety, with lower concentrations of malic and tartaric acids in grapes from symptomatic vines in both locations studied. -

Powder Denim Sky Teal Midnight Cerulean Navy Turquoise Cornflower Periwinkle Royal Opal Cmg 08458 Cmg 1 26 27 3 4 6 29 30 31 2 32 33

MARCH 2010 House Beautiful sp ring ALL COLO | A BOUT issue BLUE POWDER DENIM SKY TEAL MIDNIGHT CERULEAN NAVY TURQUOISE CORNFLOWER PERIWINKLE ROYAL OPAL CMG 08458 1 26 27 3 4 6 29 30 31 2 32 33 5 28 34 7 8 36 10 11 9 50 BLUE FABRICS 35 14 12 13 15 37 38 41 40 19 39 47 17 43 44 45 18 46 16 20 42 23 24 25 49 21 48 22 50 1 CLOQUE DE COTON 6 ARIPEKA 10 STRIATE IN AQUA. KaTE 14 CHRISSY IN DENIM. ViCTOria 18 FORMIA 22 DJEBEL 26 GASTAAD PLAID IN CaPri. 31 LA GAROUPE 35 LUCE 39 JUPON BOUQUET 43 OcELOT IN AZUL. KaT BURKI 47 KHAN CASHMERE IN COLOR 8. DOMINIQUE KIEffER IN HYdraNGEA. ROGERS GabriEL THROUGH STUdiO HaGAN HOME COLLECTION: IN RUSCELLO. DECORTEX IN GaLET. LELIEVRE THROUGH EriC COHLER FOR LEE JOfa: IN INdiGO. RALPH LaUREN IN NaVY. MadELINE WEINrib IN AZURE BLUE COLLECTION FOR IN BLUE MIX. HOLLAND BY RUBELLI THROUGH & GOffiGON: 203-532-8068. FOUR NYC: 212-475-4414. 212-888-3241. THROUGH BRUNSCHWIG STarK fabriC: 212-355-7186. 800-453-3563. HOME : 888-743-7470. ATELIER: 212-473-3000, X780. AND WarM WHITE. FORTUNY: STarK fabriC: 212-355-7186. & SHErrY: 212-355-6241. BERGAMO: 914-665-0800. & FILS: 914-684-5800. 212-753-7153. 7 MYRSINI 11 SIERRA MADRE 15 TANZANIA IN BLUE. CHarLES 23 CHEVRON BAR 27 VIOLETTA N IN MOONLIGHT. 32 WOOL SATEEN 36 AlTAI IN BLUETTE. 44 HINSON SUEDE 48 BARODA II IN INdiGO ON 2 FIORI IN ATLANTIC ON SEA MIST. -

Bougainvillea Greenthread Madagascar Periwinkle Desert Willow

TOP TEN PLANTS FOR A DESERT ISLAND Page 1 of 1 American Beautyberry Purple Trailing Lantana Callicarpa americana Lantana montevidensis 'Purple' from article in Rockport Pilot by from Dr. Michael Womack: This Ernie Edmundson: Early spring is tough plant not only blossoms most the time to cut them down before of the year, but it is also drought and they put on their new spring growth. sun hardy. The most effective use They can be trimmed back almost to of these plants is often mass the ground, however unpruned plantings in sunny areas with well- plants will develop a weeping effect drained soils. [The smaller the leaf, . with purple, or in some cases, the smaller the plant will be]. The white berries in the fall. shortest varieties of lantana commonly are called trailing lantana. Bougainvillea Madagascar Periwinkle Bougainvillea sp. Catharanthus roseus Hummingbirds are attracted to from www.wikipedia.com: It is noted bougainvillea but cannot use it for for its long flowering period, an energy source. Be careful throughout the year in tropical around play areas because of the conditions, and from spring to late thorns. Great vine for large autumn in warm temperate climates. containers to decorate hot patios Tolerates wind, bushy, thrives in and plazas. It can be trained as a humid heat. The alkaloids shrub or clipped into shapes. vincristine and vinblastine from its sap have been shown to be an effective treatment for leukaemia. Esperanza Turk's Cap Drummondii Tecoma stans Malvaviscus arboreus 'Drummondii' LARVAL HOST for: Plebeian Primary food source for migrating sphinx moth (Paratrea plebeja). -

Population Dynamics and Dispersal of Scaphoideus Titanus from Recently Recorded Infested Areas in Central-Eastern Italy

Bulletin of Insectology 67 (1): 99-107, 2014 ISSN 1721-8861 Population dynamics and dispersal of Scaphoideus titanus from recently recorded infested areas in central-eastern Italy 1 1 1 2 2 2 Paola RIOLO , Roxana Luisa MINUZ , Lucia LANDI , Sandro NARDI , Emanuela RICCI , Marina RIGHI , 1 Nunzio ISIDORO 1Dipartimento di Scienze Agrarie, Alimentari ed Ambientali, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, Italy 2Agenzia per i Servizi nel Settore Agroalimentare delle Marche (ASSAM), Servizio Fitosanitario Regione Marche, Osimo Stazione, Italy Abstract We investigated the presence of the leafhopper Scaphoideus titanus Ball in the Marche region, central Italy, during a 10-year sur- vey. Furthermore, from 2009 to 2011, yellow sticky traps were deployed to investigate the population dynamics. Taylor‟s power law and distance-weighted least-squares contour maps were used to determine the leafhopper distribution within vine fields. Po- lymerase chain reaction was used to detect Flavescence doreé (FD) phytoplasma in insect bodies. The leafhopper was first re- corded in 2007 in a commercial nursery of scion mother vines (1 specimen) in southern Pesaro-Urbino province and in 2009 in a commercial vineyard (1 specimen; the FD focus) in north-eastern Pesaro-Urbino. Adults (total, 301) were recorded from end of June to end of September, 2009-2011, with a shifted flight activity observed for females. Male captures were more abundant than females (M:F = 1.71; p < 0.001). In the site including the FD focus, insecticide treatments contributed to very low leafhopper population levels: only a few individuals (n = 4) were caught, and no phytoplasma were detected in their bodies. -

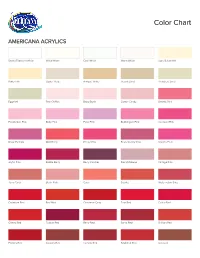

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

Insect Vectors of Phytoplasmas - R

TROPICAL BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT – Vol.VII - Insect Vectors of Phytoplasmas - R. I. Rojas- Martínez INSECT VECTORS OF PHYTOPLASMAS R. I. Rojas-Martínez Department of Plant Pathology, Colegio de Postgraduado- Campus Montecillo, México Keywords: Specificity of phytoplasmas, species diversity, host Contents 1. Introduction 2. Factors involved in the transmission of phytoplasmas by the insect vector 3. Acquisition and transmission of phytoplasmas 4. Families reported to contain species that act as vectors of phytoplasmas 5. Bactericera cockerelli Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary The principal means of dissemination of phytoplasmas is by insect vectors. The interactions between phytoplasmas and their insect vectors are, in some cases, very specific, as is suggested by the complex sequence of events that has to take place and the complex form of recognition that this entails between the two species. The commonest vectors, or at least those best known, are members of the order Homoptera of the families Cicadellidae, Cixiidae, Psyllidae, Cercopidae, Delphacidae, Derbidae, Menoplidae and Flatidae. The family with the most known species is, without doubt, the Cicadellidae (15,000 species described, perhaps 25,000 altogether), in which 88 species are known to be able to transmit phytoplasmas. In the majority of cases, the transmission is of a trans-stage form, and only in a few species has transovarial transmission been demonstrated. Thus, two forms of transmission by insects generally are known for phytoplasmas: trans-stage transmission occurs for most phytoplasmas in their interactions with their insect vectors, and transovarial transmission is known for only a few phytoplasmas. UNESCO – EOLSS 1. Introduction The phytoplasmas are non culturable parasitic prokaryotes, the mechanisms of dissemination isSAMPLE mainly by the vector insects. -

Conservation Assessment for the Reflexed Indiangrass Leafhopper (Flexamia Reflexa (Osborn and Ball))

Conservation Assessment for the Reflexed Indiangrass Leafhopper (Flexamia reflexa (Osborn and Ball)) USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region October 18, 2005 James Bess OTIS Enterprises 13501 south 750 west Wanatah, Indiana 46390 This document is undergoing peer review, comments welcome This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on the subject taxon or community; or this document was prepared by another organization and provides information to serve as a Conservation Assessment for the Eastern Region of the Forest Service. It does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if you have information that will assist in conserving the subject taxon, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service - Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 580 Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................................................ 1 NOMENCLATURE AND TAXONOMY ..................................................................................... 2 DESCRIPTION OF SPECIES....................................................................................................... -

Great Lakes Entomologist the Grea T Lakes E N Omo L O G Is T Published by the Michigan Entomological Society Vol

The Great Lakes Entomologist THE GREA Published by the Michigan Entomological Society Vol. 45, Nos. 3 & 4 Fall/Winter 2012 Volume 45 Nos. 3 & 4 ISSN 0090-0222 T LAKES Table of Contents THE Scholar, Teacher, and Mentor: A Tribute to Dr. J. E. McPherson ..............................................i E N GREAT LAKES Dr. J. E. McPherson, Educator and Researcher Extraordinaire: Biographical Sketch and T List of Publications OMO Thomas J. Henry ..................................................................................................111 J.E. McPherson – A Career of Exemplary Service and Contributions to the Entomological ENTOMOLOGIST Society of America L O George G. Kennedy .............................................................................................124 G Mcphersonarcys, a New Genus for Pentatoma aequalis Say (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) IS Donald B. Thomas ................................................................................................127 T The Stink Bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) of Missouri Robert W. Sites, Kristin B. Simpson, and Diane L. Wood ............................................134 Tymbal Morphology and Co-occurrence of Spartina Sap-feeding Insects (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha) Stephen W. Wilson ...............................................................................................164 Pentatomoidea (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae, Scutelleridae) Associated with the Dioecious Shrub Florida Rosemary, Ceratiola ericoides (Ericaceae) A. G. Wheeler, Jr. .................................................................................................183 -

Detection and Variability of Aster Yellows Phytoplasma Titer in Its Insect Vector, Macrosteles Quadrilineatus (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae)

ARTHROPODS IN RELATION TO PLANT DISEASE Detection and Variability of Aster Yellows Phytoplasma Titer in Its Insect Vector, Macrosteles quadrilineatus (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) 1 2 3 K. E. FROST, D. K. WILLIS, AND R. L. GROVES J. Econ. Entomol. 104(6): 1800Ð1815 (2011); DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/EC11183 ABSTRACT The aster yellows phytoplasma (AYp) is transmitted by the aster leafhopper, Mac- rosteles quadrilineatus Forbes, in a persistent and propagative manner. To study AYp replication and examine the variability of AYp titer in individual aster leafhoppers, we developed a quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assay to measure AYp concentration in insect DNA extracts. Absolute quantiÞcation of AYp DNA was achieved by comparing the ampliÞcation of unknown amounts of an AYp target gene sequence, elongation factor TU (tuf), from whole insect DNA extractions, to the ampliÞcation of a dilution series containing known quantities of the tuf gene sequence cloned into a plasmid. The capabilities and limitations of this method were assessed by conducting time course experiments that varied the incubation time of AYp in the aster leafhopper from 0 to 9 d after a 48 h acquisition access period on an AYp-infected plant. Average AYp titer was Ϯ measured in 107 aster leafhoppers and, expressed as Log10 (copies/insect), ranged from 3.53 ( 0.07) to 6.26 (Ϯ0.11) occurring at one and 7 d after the acquisition access period. AYp titers per insect and relative to an aster leafhopper chromosomal reference gene, cp6 wingless (cp6), increased Ϸ100-fold in insects that acquired the AYp. High quantiÞcation cycle values obtained for aster leafhoppers not exposed to an AYp-infected plant were interpreted as background and used to deÞne a limit of detection for the quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assay.