Journal of South Asian Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release South Malabar Steels and Alloys Private Limited

Press Release South Malabar Steels and Alloys Private Limited February 11, 2021 Ratings Amount Facilities Rating1 Rating Action (Rs. crore) Revised from CARE BB; CARE BB-; Stable; Stable (Double B; Outlook: ISSUER NOT COOPERATING* Long -term Bank Facilities 7.52 Stable) and moved to (Double B Minus; Outlook: Stable; ISSUER NOT COOPERATING ISSUER NOT COOPERATING*) category CARE A4; Rating moved to ISSUER ISSUER NOT COOPERATING* NOT COOPERATING Short-term Bank Facilities 1.50 (A Four; category ISSUER NOT COOPERATING*) 9.02 Total Facilities (Rs. Nine Crores and Two Lakhs Only) Details of facilities in Annexure-1 *Based on best available information Detailed Rationale & Key Rating Drivers CARE has been seeking information, to carry out annual surveillance, from South Malabar Steels and Alloys Private Limited (SMSAPL) to monitor the rating(s) vide e-mail communications dated January 14, 2021, January 21, 2021, January 25, 2021, January 27, 2021 and numerous phone calls. However despite our repeated requests, the company has not provided the information for monitoring the requisite ratings. In line with the extant SEBI guidelines, CARE has reviewed the rating on the basis of the best available information which however, in CARE’s opinion is not sufficient to arrive at a fair rating. The rating on South Malabar Steels and Alloys Private Limited bank facilities will now be denoted as CARE BB-; Stable/CARE A4; ISSUER NOT COOPERATING. Further due diligence with the lender and auditor could not be conducted. Users of this rating (including investors, lenders and the public at large) are hence requested to exercise caution while using the above rating. -

BSW 043 Block 1 English.Pmd

BSW-043 TRIBALS OF SOUTH Indira Gandhi AND CENTRAL INDIA National Open University School of Social Work Block 1 TRIBES OF SOUTH INDIA UNIT 1 Tribes of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana 5 UNIT 2 Tribes of Karnataka 17 UNIT 3 Tribes of Kerala 27 UNIT 4 Tribes of Tamil Nadu 38 UNIT 5 Tribes of Lakshadweep and Puducherry 45 EXPERT COMMITTEE Prof. Virginius Xaxa Dr. Archana Kaushik Dr. Saumya Director – Tata Institute of Associate Professor Faculty Social Sciences Department of Social Work School of Social Work Uzanbazar, Guwahati Delhi University IGNOU, New Delhi Prof. Hilarius Beck Dr. Ranjit Tigga Dr. G. Mahesh Centre for Community Department of Tribal Studies Faculty Organization and Development Indian Social Institute School of Social Work Practice Lodhi Road, New Delhi IGNOU, New Delhi School of Social Work Prof. Gracious Thomas Dr. Sayantani Guin Deonar, Mumbai Faculty Faculty Prof. Tiplut Nongbri School of Social Work School of Social Work Centre for the Study of Social IGNOU, New Delhi IGNOU, New Delhi Systems Dr. Rose Nembiakkim Dr. Ramya Jawaharlal Nehru University Director Faculty New Delhi School of Social Work School of Social Work IGNOU, New Delhi IGNOU, New Delhi COURSE PREPARATION TEAM Block Preparation Team Programme Coordinator Unit 1 Anindita Majumdar Dr. Rose Nembiakkim and Dr. Aneesh Director Unit 2 & 3 Rubina Nusrat School of Social Work Unit 4 Mercy Vungthianmuang IGNOU Unit 5 Dr. Grace Donnemching PRINT PRODUCTION Mr. Kulwant Singh Assistant Registrar (P) SOSW, IGNOU August, 2018 © Indira Gandhi National Open University, 2018 ISBN-978-93-87237-69-8 All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission in writing from the Indira Gandhi National Open University. -

O R D E R Mr. Askarali. a Department UG in Economics Has Been Nominated As the Mentor to the Students (Mentees) Listed Below

PROCEEDINGS OF THE PRINCIPAL EMEA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE, KONDOTTI Sub: Mentoring Scheme 2018-19 - Orders Issued. ORDER NO. G4-SAS /101/2018 16.07.2018 O R D E R Mr. Askarali. A department UG in Economics has been nominated as the mentor to the students (mentees) listed below for the academic year 2018-19. III/IV UG ECONOMICS Sl Roll Admn Second Student Name Gender Religion Caste Category No No No Language 1 1 10286 ANEESH.C Arabic Male Islam MAPPILA OBC 2 2 10340 FAREEDA FARSANA K Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 3 4 10195 FATHIMA SULFANA PT Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC HAFNASHAHANA 4 5 10397 Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC KANNACHANTHODI 5 6 10098 HAFSA . V.P Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 6 7 10250 HEDILATH.C Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 7 8 10194 HUSNA NARAKKODAN Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 8 9 10100 JASLA.K.K Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 9 10 10016 KHADEEJA SHERIN.A.K Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 10 12 10050 MASHUDA.K Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 11 13 10188 MOHAMED ANEES .PK Arabic Male MUSLIM MAPPILA OBC 12 14 10171 NASEEBA.V Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 13 15 10052 NASEEFA.P Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 14 16 10064 NOUFIRA .A.P Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 15 17 10296 ROSNA.T Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 16 19 10209 SAHLA.A.C Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 17 20 10342 SALVA SHERIN.N.T Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 18 21 10244 SHABEERALI N T Arabic Male Islam MAPPILA OBC 19 22 10260 SHABNAS.P Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 20 23 10338 SHAHANA JASI A Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 21 24 10339 SHAHINA.V Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 22 25 10030 SHAKIRA.MT Arabic Female Islam OBC PROCEEDINGS OF THE PRINCIPAL EMEA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE, KONDOTTI Sub: Mentoring Scheme 2018-19 - Orders Issued. -

Malaria Control in South Malabar, Madras State

Bull. Org. mond. Sante | 1954, 11, 679-723 Bull. Wld Hlth Org. MALARIA CONTROL IN SOUTH MALABAR, MADRAS STATE L. MARA, M.D. Senior Adviser and Team-leader, WHO Malaria-Control Demonstration Team, Suleimaniya, Iraq formerly, Senior Adviser and Team-leader, WHO Malaria-Control Demonstration Team, South Malabar Manuscript received in January 1954 SYNOPSIS The author describes the activities and achievements of a two- year malaria-control demonstration-organized by WHO, UNICEF, the Indian Government, and the Government of Madras State- in South Malabar. Widespread insecticidal work, using a dosage of 200 mg of DDT per square foot (2.2 g per m2), protected 52,500 people in 1950, and 115,500 in 1951, at a cost of about Rs 0/13/0 (US$0.16) per capita. The final results showed a considerable decrease in the size of the endemic areas; in the spleen- and parasite-rates of children; and in the number of malaria cases detected by the team or treated in local hospitals and dispensaries. During December 1949 a malaria-control project, undertaken jointly by WHO, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the Govern- ment of India, and the Government of Madras State, started operations in the malarious areas among the foothills and tracts of Ernad and Walavanad taluks in South Malabar. During 1951 the operational area was extended to include almost all the malarious parts of Ernad and Walavanad as well as the northernmost part of Palghat taluk (see map 1 a). The staff of the international team provided by WHO consisted of a senior adviser and team-leader and a public-health nurse. -

Role of the Muslim Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in the Colonial Punjab: a Historical Analysis

Bulletin of Education and Research December 2019, Vol. 41, No. 3 pp. 1-18 Role of the Muslim Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in the Colonial Punjab: A Historical Analysis Maqbool Ahmad Awan* __________________________________________________________________ Abstract This article highlightsthe vibrant role of the Muslim Anjumans in activating the educational revival in the colonial Punjab. The latter half of the 19th century, particularly the decade 1880- 1890, witnessed the birth of several Muslim Anjumans (societies) in the Punjab province. These were, in fact, a product of growing political consciousness and desire for collective efforts for the community-betterment. The Muslims, in other provinces, were lagging behind in education and other avenues of material prosperity. Their social conditions were also far from being satisfactory. Religion too had become a collection of rites and superstitions and an obstacle for their educational progress. During the same period, they also faced a grievous threat from the increasing proselytizing activities of the Christian Missionary societies and the growing economic prosperity of the Hindus who by virtue of their advancement in education, commerce and public services, were emerging as a dominant community in the province. The Anjumans rescued the Muslim youth from the verge of what then seemed imminent doom of ignorance by establishing schools and madrassas in almost all cities of the Punjab. The focus of these Anjumans was on both secular and religious education, which was advocated equally for both genders. Their trained scholars confronted the anti-Islamic activities of the Christian missionaries. The educational development of the Muslims in the Colonial Punjab owes much to these Anjumans. -

Patterns of Affliction Among Mappila Muslims of Malappuram, Kerala

International Journal of Management and Applied Science, ISSN: 2394-7926 Volume-4, Issue-10, Oct.-2018 http://iraj.in PATTERNS OF AFFLICTION AMONG MAPPILA MUSLIMS OF MALAPPURAM, KERALA FARSANA K.P Research Scholar Centre of Social Medicine and Community Health, JNU E-mail: [email protected] Abstract- Each and every community has its own way of understanding on health and illness; it varies from Culture to culture. According to the Mappila Muslims of Malappuram, the state of pain, distress and misery is understood as an affliction to their health. They believe that most of the afflictions are due to the Jinn/ Shaitanic Possession. So they prefer religious healers than the other systems of medicine for their treatments. Thangals are the endogamous community in Kerala, of Yemeni heritage who claim direct descent from the Prophet Mohammed’s family. Because of their sacrosanct status, many Thangals works as religious healers in Northern Kerala. Using the case of one Thangal healer as illustration of the many religious healers in Kerala who engage in the healing practices, I illustrate the patterns of afflictions among Mappila Muslims of Malappuram. Based on the analysis of this Thangal’s healing practice in the local context of Northern Kerala, I further discuss about the modes of treatment which they are providing to them. Key words- Affliction, Religious healing, Faith, Mappila Muslims and Jinn/Shaitanic possession I. INTRODUCTION are certain healing concepts that traditional cultures share. However, healing occupies an important The World Health Organization defined health as a position in religious experiences irrespective of any state of complete physical, social and mental religion. -

Kle Law Academy Belagavi

KLE LAW ACADEMY BELAGAVI (Constituent Colleges: KLE Society’s Law College, Bengaluru, Gurusiddappa Kotambri Law College, Hubballi, S.A. Manvi Law College, Gadag, KLE Society’s B.V. Bellad Law College, Belagavi, KLE Law College, Chikodi, and KLE College of Law, Kalamboli, Navi Mumbai) STUDY MATERIAL for FAMILY LAW II Prepared as per the syllabus prescribed by Karnataka State Law University (KSLU), Hubballi Compiled by Reviewed by Dr. Jyoti G. Hiremath, Asst.Prof. Dr. B Jayasimha, Principal B.V. Bellad Law College, Belagavi This study material is intended to be used as supplementary material to the online classes and recorded video lectures. It is prepared for the sole purpose of guiding the students in preparation for their examinations. Utmost care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the content. However, it is stressed that this material is not meant to be used as a replacement for textbooks or commentaries on the subject. This is a compilation and the authors take no credit for the originality of the content. Acknowledgement, wherever due, has been provided. II SEMESTER LL.B. AND VI SEMESTER B.A.LL.B. COURSE - V : FAMILY LAW - II : MOHAMMEDAN LAW AND INDIAN SUCCESSION ACT CLASS NOTES Contents Part I - : Mohammedan Law : (127 pages) 1. Application of Muslim Law 2. History, Concept and Schools of Muslim Law 3. Sources of Muslim Law 4. Marriage 5. Mahr / Dower 6. Dissolution of marriage and Matrimonial Reliefs 7. Parentage 8. Guardianship and Hizanat 9. Maintenance 10. The Muslim Women(Protection of Rights on Divorce)Act,1986 11. Hiba / Gifts 12. Administration of Estate 13. -

MUSLIM LEADERSHIP in U. P. 1906-1937 ©Ottor of ^Liilogoplip

MUSLIM LEADERSHIP IN U. P. 1906-1937 OAMAV''^ ***' THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF ©ottor of ^liilogoplip IN Jlis^torp Supervisor Research scholar umar cKai Head Department of History Banaras Hindu University VaranaSi-221005 FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES BANARAS HINDU UNIVERSITY VARANASI-221005 Enrolment No.-l 73954 Year 1994 D©NATED BY PROF Z. U. SIDDIQUI DEPT. OF HISTORY. A.M.U. T5235 Poll * TtU. OJfiet : BADUM Hindu Univenity Q»3H TeUphone : 310291—99 (PABX) Sailwaj/Station Vkranui Cantt. SS^^/ Telex ;645 304 BHU IN Banaras Hindu University VARANASI—221005 R^. No..^ _ IMPARWBif 99 HliiOllir 2)ate<i - 9lftlfltilt Bft#fi titii Stall flf Ifti ffti1?t QfilifllfttI !Uiiitii X te*M^ c«rtify tHat ttM thatit •! Sti A^«k Kunat fttl. MiltUd ^Htfllii tM&mw^tp III U.F, ElitwMfi (t9%^im)»* Htm f««i»««^ fdMlAi iHMlit mf awp«rviai«n in tti« D»p«ftMifit of Hitt^y* Facility 9i So€i«d SdL«nc«t« n&ntwmM Hindu Ufiiv«rtity« ™—- j>v ' 6 jjj^ (SUM.) K.S. SMitte 0»»««tMllt of ^tj^£a»rtmentrfHj,,0| ^ OO^OttMOt of Hittflf SaAovoo Hin^ llRiiSaSu^iifi Sec .. ^^*^21. »«»•»•• Htm At Uiivovoity >^otflR«ti • 391 005' Dep«tfY>ent of History FACULTY OF SOCIAL S' ENCES Bsnafas Hir-y Unlvacsitv CONTENTS Page No. PREFACE 1 - IV ARBRBVIATIONS V INTRODUCTION ... 1-56 CHAPTER I : BIRTH OF fvUSLiM LEAaJE AND LEADERSHIP IN U .P . UPTO 1916 ... 57-96 CHAPTER II MUSLIM LEADERSHIP IN U .P . DURING KHILAFAT AND NON CO-OPERATION MO ^fAENT ... 97-163 CHAPTER III MUSLIM POLITICS AND LEADERSHIP IN U.P, DURING Sy/AR.AJIST BRA ...164 - 227 CHAPTER IV : MUSLL\^S ATflTUDE AND LEADERSHIP IN U.P. -

Translatability of the Qur'an In

TRANSLATABILITY OF THE QUR’AN IN REGIONAL VERNACULAR: DISCOURSES AND DIVERSITIES WITHIN THE MAPPILA MUSLIMS OF KERALA, INDIA BY MUHAMMED SUHAIL K A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Qur’an and Sunnah Studies Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences International Islamic University Malaysia JULY 2020 ABSTRACT Engagements of non-Arab Muslim communities with the Qur’an, the Arabic-specific scripture of Islam, are always in a form of improvement. Although a number of theological and linguistic aspects complicate the issue of translatability of the Qur’an, several communities have gradually embraced the practice of translating it. The case of Mappila Muslims of Kerala, India, the earliest individual Muslim community of south Asia, is not different. There is a void of adequate academic attention on translations of the Qur’an into regional vernaculars along with their respective communities in general, and Malayalam and the rich Mappila context, in particular. Thus, this research attempts to critically appraise the Mappila engagements with the Qur’an focusing on its translatability-discourses and methodological diversities. In order to achieve this, the procedure employed is a combination of different research methods, namely, inductive, analytical, historical and critical. The study suggests that, even in its pre-translation era, the Mappilas have uninterruptedly exercised different forms of oral translation in an attempt to comprehend the meaning of the Qur’an both at the micro and macro levels. The translation era, which commences from the late 18th century, witnessed the emergence of huge number of Qur’an translations intertwined with intense debates on its translatability. -

The First National Conference Government in Jammu and Kashmir, 1948-53

THE FIRST NATIONAL CONFERENCE GOVERNMENT IN JAMMU AND KASHMIR, 1948-53 THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy IN HISTORY BY SAFEER AHMAD BHAT Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. ISHRAT ALAM CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2019 CANDIDATE’S DECLARATION I, Safeer Ahmad Bhat, Centre of Advanced Study, Department of History, certify that the work embodied in this Ph.D. thesis is my own bonafide work carried out by me under the supervision of Prof. Ishrat Alam at Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. The matter embodied in this Ph.D. thesis has not been submitted for the award of any other degree. I declare that I have faithfully acknowledged, given credit to and referred to the researchers wherever their works have been cited in the text and the body of the thesis. I further certify that I have not willfully lifted up some other’s work, para, text, data, result, etc. reported in the journals, books, magazines, reports, dissertations, theses, etc., or available at web-sites and included them in this Ph.D. thesis and cited as my own work. The manuscript has been subjected to plagiarism check by Urkund software. Date: ………………… (Signature of the candidate) (Name of the candidate) Certificate from the Supervisor Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University This is to certify that the above statement made by the candidate is correct to the best of my knowledge. Prof. Ishrat Alam Professor, CAS, Department of History, AMU (Signature of the Chairman of the Department with seal) COURSE/COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION/PRE- SUBMISSION SEMINAR COMPLETION CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Mr. -

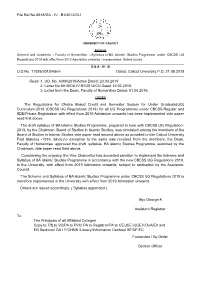

U.O.No. 11099/2019/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 21.08.2019 Biju George K Assistant Registrar Forwarded / by Order Section

File Ref.No.8818/GA - IV - B1/2012/CU UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT Abstract General and Academic - Faculty o f Humanities - Syllabus o f BA Islamic Studies Programme under CBCSS UG Regulations 2019 with effect from 2019 Admission onwards - Implemented- Orders issued G & A - IV - B U.O.No. 11099/2019/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 21.08.2019 Read:-1. UO. No. 4368/2019/Admn Dated: 23.03.2019 2. Letter No.8818/GA IV B1/2012/CU Dated:15.06.2019. 3. Letter from the Dean, Faculty of Humanities Dated: 01.08.2019. ORDER The Regulations for Choice Based Credit and Semester System for Under Graduate(UG) Curriculum-2019 (CBCSS UG Regulations 2019) for all UG Programmes under CBCSS-Regular and SDE/Private Registration with effect from 2019 Admission onwards has been implemented vide paper read first above. The draft syllabus of BA Islamic Studies Programme, prepared in tune with CBCSS UG Regulation- 2019, by the Chairman, Board of Studies in Islamic Studies, was circulated among the members of the Board of Studies in Islamic Studies vide paper read second above as provided under Calicut University First Statutes -1976. Since,no exception to the same was received from the members, the Dean, Faculty of Humanities approved the draft syllabus BA Islamic Studies Programme, submited by the Chairman, vide paper read third above. Considering the urgency, the Vice Chancellor has accorded sanction to implement the Scheme and Syllabus of BA Islamic Studies Programme in accordance with the new CBCSS UG Regulations 2019, in the University, with effect from 2019 Admission onwards, subject to ratification by the Academic Council. -

Dictionary of Martyrs: India's Freedom Struggle

DICTIONARY OF MARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala ii Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 DICTIONARY OF MARTYRSMARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala General Editor Arvind P. Jamkhedkar Chairman, ICHR Executive Editor Rajaneesh Kumar Shukla Member Secretary, ICHR Research Consultant Amit Kumar Gupta Research and Editorial Team Ashfaque Ali Md. Naushad Ali Md. Shakeeb Athar Muhammad Niyas A. Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF IDNIA AND INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH iv Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH First Edition 2018 Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE Government of India and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH 35, Ferozeshah Road, New Delhi - 110 001 © ICHR & Ministry of Culture, GoI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 978-81-938176-1-2 Printed in India by MANAK PUBLICATIONS PVT. LTD B-7, Saraswati Complex, Subhash Chowk, Laxmi Nagar, New Delhi 110092 INDIA Phone: 22453894, 22042529 [email protected] State Co-ordinators and their Researchers Andhra Pradesh & Telangana Karnataka (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) V. Ramakrishna B. Surendra Rao S.K. Aruni Research Assistants Research Assistants V. Ramakrishna Reddy A.B. Vaggar I. Sudarshan Rao Ravindranath B.Venkataiah Tamil Nadu Kerala (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) N.