A Leader in the Struggle for Justice1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release

MEDIA RELEASE 7 February 2017 Premier awards Tennyson Medal at SACE Merit Ceremony The Premier of South Australia, the Hon. Jay Weatherill MP, awarded the prestigious Tennyson Medal for excellence in English Studies to 2016 Year 12 graduate, Ashleigh Jones at the SACE Merit Ceremony at Government House today. The ceremony, in its twenty-ninth year, saw 996 students awarded with 1302 subject merits for outstanding achievement in SACE Stage 2 subjects. Subject merits are awarded to students who gain an overall subject grade of A+ and demonstrate exceptional achievement in that subject. As part of the Merit Ceremony, His Excellency the Hon. Hieu Van Le AC, the Governor of South Australia, presented the following awards: Governor of South Australia Commendation for outstanding overall achievement in the SACE (twenty-five recipients in 2016) Governor of South Australia Commendation — Aboriginal Student SACE Award for the Aboriginal student with the highest overall achievement in the SACE Governor of South Australia Commendation – Excellence in Modified SACE Award for the student with an identified intellectual disability who demonstrates outstanding achievement exclusively through SACE modified subjects. The Tennyson Medal dates back to 1901 when the former Governor of South Australia, Lord Tennyson, established the Tennyson Medal to encourage the study of English literature. The long list of recipients includes the late John Bannon AO, 39th Premier of South Australia, who was awarded the medal in 1961. For her Year 12 English Studies, Ashleigh studied works by Henrik Ibsen (A Doll’s House), Zhang Yimou who directed Raise the Red Lantern, and Tennessee Williams (The Glass Menagerie). -

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia Clare Parker BMusSt, BA(Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Discipline of History, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Adelaide. August 2013 ii Contents Contents ii Abstract iv Declaration vi Acknowledgements vii List of Abbreviations ix List of Figures x A Note on Terms xi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: ‘The Practice of Sound Morality’ 21 Policing Abortion and Homosexuality 24 Public Conversation 36 The Wowser State 44 Chapter 2: A Path to Abortion Law Reform 56 The 1930s: Doctors, Court Cases and Activism 57 World War II 65 The Effects of Thalidomide 70 Reform in Britain: A Seven Month Catalyst for South Australia 79 Chapter 3: The Abortion Debates 87 The Medical Profession 90 The Churches 94 Activism 102 Public Opinion and the Media 112 The Parliamentary Debates 118 Voting Patterns 129 iii Chapter 4: A Path to Homosexual Law Reform 139 Professional Publications and Prohibited Literature 140 Homosexual Visibility in Australia 150 The Death of Dr Duncan 160 Chapter 5: The Homosexuality Debates 166 Activism 167 The Churches and the Medical Profession 179 The Media and Public Opinion 185 The Parliamentary Debates 190 1973 to 1975 206 Conclusion 211 Moral Law Reform and the Public Interest 211 Progressive Reform in South Australia 220 The Slippery Slope 230 Bibliography 232 iv Abstract This thesis examines the circumstances that permitted South Australia’s pioneering legalisation of abortion and male homosexual acts in 1969 and 1972. It asks how and why, at that time in South Australian history, the state’s parliament was willing and able to relax controls over behaviours that were traditionally considered immoral. -

Sixteen Years of Labor Government in South Australia, 2002-2018

AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW Parliament in the Periphery: Sixteen Years of Labor Government in South Australia, 2002-2018* Mark Dean Research Associate, Australian Industrial Transformation Institute, Flinders University of South Australia * Double-blind reviewed article. Abstract This article examines the sixteen years of Labor government in South Australia from 2002 to 2018. With reference to industry policy and strategy in the context of deindustrialisation, it analyses the impact and implications of policy choices made under Premiers Mike Rann and Jay Weatherill in attempts to progress South Australia beyond its growing status as a ‘rustbelt state’. Previous research has shown how, despite half of Labor’s term in office as a minority government and Rann’s apparent disregard for the Parliament, the executive’s ‘third way’ brand of policymaking was a powerful force in shaping the State’s development. This article approaches this contention from a new perspective to suggest that although this approach produced innovative policy outcomes, these were a vehicle for neo-liberal transformations to the State’s institutions. In strategically avoiding much legislative scrutiny, the Rann and Weatherill governments’ brand of policymaking was arguably unable to produce a coordinated response to South Australia’s deindustrialisation in a State historically shaped by more interventionist government and a clear role for the legislature. In undermining public services and hollowing out policy, the Rann and Wethearill governments reflected the path dependency of responses to earlier neo-liberal reforms, further entrenching neo-liberal responses to social and economic crisis and aiding a smooth transition to Liberal government in 2018. INTRODUCTION For sixteen years, from March 2002 to March 2018, South Australia was governed by the Labor Party. -

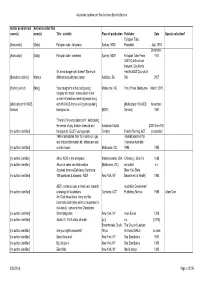

Bonython) Determination 2006 (No 1)

Australian Capital Territory Public Place Names (Bonython) Determination 2006 (No 1) Disallowable instrument DI2006 - 255 made under the Public Place Names Act 1989— section 3 (Minister to determine names) I DETERMINE the names of the public places that are Territory land as specified in the attached schedule and as indicated on the associated plan. Neil Savery Delegate of the Minister 11 December 2006 Page 1 of 10 Public Place Names (Bonython) Determination 2006 (No 1) Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au SCHEDULE Public Place Names (Bonython) Determination 2006 (No 1) Division of Bonython: Famous South Australians, particularly journalists and South Australian districts. NAME ORIGIN SIGNIFICANCE Burgoyne Thomas Burgoyne South Australian - journalist, builder and politician. Street (1827-1920) Thomas Burgoyne was born in Wales. He immigrated to Australia and arrived in South Australia in 1848. As a builder, in 1856 he erected the first permanent building in Port Augusta and designed St Augustine's Church. The design of Holowiliena homestead and its out buildings are also attributed to Thomas. He was appointed the first Town Clerk and Surveyor of Port Augusta in 1875 to 1879. He was Councillor from 1879-81 and Mayor in 1882. He was a correspondent for the `South Australian Register' from 1864. In 1877 he founded the `Port Augusta Dispatch' and was its Editor for three years. He held the position of Commissioner for Crown Lands and Immigration from 1889 to 1890. Page 2 Public Place Names (Bonython) Determination 2006 (No 1) Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au NAME ORIGIN SIGNIFICANCE Don Dunstan Donald Allan Premier of South Australia Drive Dunstan Donald Allan Dunstan was born in Suva, Fiji. -

Annual Report 2004-2005

Annual Report 2004/2005 Governing partners Supported by Contents Report from the Chair of Trustees 4 Summary of Activities: “There is still much to be done” 6 Foundation Year in Review 10 Trustees’ Report 22 • Statement of Financial Performance 23 • Statement of Financial Position 24 • Statement of Cash Flows 25 • Notes to the Financial Statements 26 • Declaration by Trustees 35 • Independent Audit Report 36 Trustees, Board and Staff 38 Our supporters 40 The Annual Report Published March 2006 By the Don Dunstan Foundation Level 3, 10 Pulteney Street The University of Adelaide, SA 5005 http://www.dunstan.org.au ABN 71 448 549 600 Don Dunstan Foundation Annual Report 2004/2005 Page 2/40 Don Dunstan Foundation Values • Respect for fundamental human rights • Celebration of cultural and ethnic diversity • Freedom of individuals to control their lives • Just distribution of global wealth • Respect for indigenous people and protection of their rights • Democratic and inclusive forms of governance Strategic Directions • Facilitate a productive exchange between academic researchers and Government policy makers • Invigorate policy debate and responses • Consolidate and expand the Foundation’s links with the wider community • Support Chapter activities • Build and maintain the long-term viability of the Foundation Don Dunstan Foundation Annual Report 2004/2005 Page 3/40 REPORT FROM THE CHAIR The financial year 2004/2005 has been extremely productive with the Foundation continuing its drive to implement its Strategic Directions and Strategic Business Plan. The Foundation has provided an array of targeted events, pursued key projects of community benefit, enhanced its infrastructure and promoted its contribution to the wider South Australian Community. -

Books at 2016 05 05 for Website.Xlsx

Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Book Collection Author or editor last Author or editor first name(s) name(s) Title : sub-title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection? Fallopian Tube [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : fallopiana Sydney, NSW Pamphlet July, 1974 December, [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : madness Sydney, NSW Fallopian Tube Press 1974 GLBTIQ with cancer Network, Gay Men's It's a real bugger isn't it dear? Stories of Health (AIDS Council of [Beresford (editor)] Marcus different sexuality and cancer Adelaide, SA SA) 2007 [Hutton] (editor) [Marg] Your daughter's at the door [poetry] Melbourne, VIC Panic Press, Melbourne March, 1975 Inequity and hope : a discussion of the current information needs of people living [Multicultural HIV/AIDS with HIV/AIDS from non-English speaking [Multicultural HIV/AIDS November, Service] backgrounds [NSW] Service] 1997 "There's 2 in every classroom" : Addressing the needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual and Australian Capital [2001 from 100 [no author identified] transgender (GLBT) young people Territory Family Planning, ACT yr calendar] 1995 International Year for Tolerance : gay International Year for and lesbian information kit : milestones and Tolerance Australia [no author identified] current issues Melbourne, VIC 1995 1995 [no author identified] About AIDS in the workplace Massachusetts, USA Channing L Bete Co 1988 [no author identified] Abuse in same sex relationships [Melbourne, VIC] not stated n.d. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome : [New York State [no author identified] 100 questions & answers : AIDS New York, NY Department of Health] 1985 AIDS : a time to care, a time to act, towards Australian Government [no author identified] a strategy for Australians Canberra, ACT Publishing Service 1988 Adam Carr And God bless Uncle Harry and his roommate Jack (who we're not supposed to talk about) : cartoons from Christopher [no author identified] Street Magazine New York, NY Avon Books 1978 [no author identified] Apollo 75 : Pix & story, all male [s.l.] s.n. -

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other Accounts of Constitution-Makers, Constitutions and Citizenship

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other accounts of constitution-makers, constitutions and citizenship This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2005 Geoffrey Trenorden BA Honours (Murdoch) Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………….. Geoffrey Trenorden ii Abstract As argued throughout this thesis, in his personification of the federal story, if not immediately in his formulation of its paternity, Deakin’s unpublished memoirs anticipated the way that federation became codified in public memory. The long and tortuous process of federation was rendered intelligible by turning it into a narrative set around a series of key events. For coherence and dramatic momentum the narrative dwelt on the activities of, and words of, several notable figures. To explain the complex issues at stake it relied on memorable metaphors, images and descriptions. Analyses of class, citizenship, or the industrial confrontations of the 1890s, are given little or no coverage in Deakinite accounts. Collectively, these accounts are told in the words of the victors, presented in the images of the victors, clothed in the prejudices and predilections of the victors, while the losers are largely excluded. Those who spoke out against or doubted the suitability of the constitution, for whatever reason, have largely been removed from the dominant accounts of constitution-making. More often than not they have been ‘character assassinated’ or held up to public ridicule by Alfred Deakin, the master narrator of the Conventions and federation movement and by his latter-day disciples. -

Heritage Politics in Adelaide

Welcome to the electronic edition of Heritage Politics in Adelaide. The book opens with the bookmark panel and you will see the contents page. Click on this anytime to return to the contents. You can also add your own bookmarks. Each chapter heading in the contents table is clickable and will take you direct to the chapter. Return using the contents link in the bookmarks. The whole document is fully searchable. Enjoy. Heritage Politics in Adelaide For David and for all the other members of Aurora Heritage Action, Inc. Explorations and Encounters in FRENCH Heritage Politics EDITED BY JEAN FOinRNASIERO Adelaide AND COLETTE MROWa-HopkiNS Sharon Mosler Selected Essays from the Inaugural Conference of the Federation of Associations of Teachers of French in Australia Published in Adelaide by University of Adelaide Press Barr Smith Library The University of Adelaide South Australia 5005 [email protected] www.adelaide.edu.au/press The University of Adelaide Press publishes externally refereed scholarly books by staff of the University of Adelaide. It aims to maximise the accessibility to its best research by publishing works through the internet as free downloads and as high quality printed volumes on demand. Electronic Index: this book is available from the website as a down-loadable PDF with fully searchable text. Please use the electronic version to complement the index. © 2011 Sharon Mosler This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission. -

A Social History of Thebarton

A Social History of Thebarton Copyright – Haydon R Manning All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Haydon Manning This manuscript was never published by my father or subject to editorial review. Contents Chapter 1 The Aborigines of the Adelaide Plains 2 Colonel William Light - Surveyor of Adelaide 3 Colonel William Light - His Final Days 4 The Village of Thebarton 5 Housing, Domestic Life and Leisure Activities 6 Sources for Water Supply 7 Industries - A WorKplace for the Labour Force of Thebarton 8 Industrial Relations in Respect of the Thebarton WorK Force; Destitution, Charity and Unemployment - 1837-1900 9 Sport 10 Transport and Public Utilities 11 Education 12 Local Government and Civic Affairs 13 Religion 14 A Day in the Life of Thebarton - 1907 15 The Public Health of Thebarton 16 The Role of Women in the Community Appendix A - Information on the 344 Allotments in Thebarton Subdivided by Colonel William Light and Maria Gandy Appendix B - Nomenclature of Streets Appendix C – Information on Town ClerKs and Mayors Thebarton’s First Occupants - The Kaurna People - Contributed by Tom Gara (hereunder) 1 Chapter 1 The Aborigines of the Adelaide Plains Shame upon us! We take their land and drive away their food by what we call civilisation and then deny them shelter from a storm... What comes of all the hypocrisy of our wishes to better their condition?... The police drive them into the bush to murder shepherds, and then we cry out for more police.. -

Getting to the Future First

Getting to the Future First Susan Greenfield Thinker in Residence 2004-2005 Susan Greenfi eld | Getting to the Future First Getting to the Future First Prepared by Baroness Professor Susan Greenfi eld Department of the Premier and Cabinet c/- GPO Box 2343 Adelaide SA 5001 January 2006 ©All rights reserved – Crown – in right of the State of South Australia ISBN 0-9752027-7-4 www.thinkers.sa.gov.au 1 Baroness Professor Foreword Susan Greenfi eld Baroness Professor Susan Greenfi eld is a Baroness Professor Susan Greenfi eld is making She has put forward a number of other pioneering scientist, an entrepreneur, a an outstanding contribution to South Australia valuable ideas as part of the recommendations communicator of science and a policy adviser. – and the public’s understanding of science. in this report, which I commend to all those interested in improving science literacy and Susan has long been regarded as a world- She came to us with a reputation as being awareness. leading expert on the human brain, and is one of the most infl uential and inspirational widely known for her research into Parkinson’s women in the world – as both a pioneering I thank Baroness Greenfi eld for her hard work and Alzheimer’s disease. She has received a life scientist and a gifted communicator. and generosity of spirit, and for continuing to peerage and a CBE in the United Kingdom. make a difference to South Australia. While in Adelaide, as our Thinker in Residence, Susan is the fi rst woman to lead the she shared her insights into the human brain prestigious Royal Institution of Great Britain – how it works, how it copes with ageing and and also holds the positions of Senior Research how it responds to drugs, for example. -

Unclaimed Bank Balances

Unclaimed Bank Balances “Section 126 of the Banking Services Act requires the publication of the following data in a newspaper at least two (2) times over a one (1) year period.” This will give persons the opportunity to claim these monies. If these monies remain unclaimed at the end of the year, they will become a part of the revenues of the Jamaican Government. SAGICOR BANK BALANCE Name Last Transaction Date Account Number Balance Name Last Transaction Date Account Number Balance JMD JMD ALMA J BROWN 7-Feb-01 5500866545 32.86 ALMA M HENRY 31-Dec-97 5501145809 3,789.62 0150L LYNCH 13-Jun-86 5500040485 3,189.49 ALMAN ARMSTRONG 22-Nov-96 5500388252 34.27 A A R PSYCHOLOGICAL SERVICES CENTRE 30-Sep-97 5500073766 18,469.06 ALMANEITA PORTER 7-Nov-02 5500288665 439.42 A F FRANCIS 29-Sep-95 5500930588 23,312.81 ALMARIE HOOPER 19-Jan-98 5500472978 74.04 A H BUILDINGS JAMAICA LTD 30-Sep-93 5500137705 12,145.92 ALMENIA LEVY 27-Oct-93 5500966582 40,289.27 A LEONARD MOSES LTD 20-Nov-95 5500108993 531,889.69 ALMIRA SOARES 18-Feb-03 5501025951 12,013.42 A ROSE 13-Jun-86 5500921767 20,289.21 ALPHANSO C KENNEDY 8-Jul-02 5500622379 34,077.58 AARON H PARKE 27-Dec-02 5501088128 10,858.10 ALPHANSO LOVELACE 12-Dec-03 5500737354 69,295.14 ADA HAMILTON 30-Jan-83 5500001528 35,341.90 ALPHANSON TUCKER 10-Jan-96 5500969131 48,061.09 ADA THOMPSON 5-May-97 5500006511 9,815.70 ALPHANZO HAMILTON 12-Apr-01 5500166397 8,633.90 ADASSA DOWDEN SCHOLARSHIP 20-Jan-00 5500923328 299.66 ALPHONSO LEDGISTER 15-Feb-00 5500087945 58,725.08 ADASSA ELSON 28-Apr-99 5500071739 71.13 -

The Constitution Makers

Papers on Parliament No. 30 November 1997 The Constitution Makers _________________________________ Published and Printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031–976X Published 1997 Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Editors of this issue: Kathleen Dermody and Kay Walsh. All inquiries should be made to: The Director of Research Procedure Office Department of the Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (06) 277 3078 ISSN 1031–976X Cover design: Conroy + Donovan, Canberra Cover illustration: The federal badge, Town and Country Journal, 28 May 1898, p. 14. Contents 1. Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies 1 The Hon. John Bannon 2. A Federal Commonwealth, an Australian Citizenship 19 Professor Stuart Macintyre 3. The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention 33 Professor Geoffrey Bolton 4. Sir Richard Chaffey Baker—the Senate’s First Republican 49 Dr Mark McKenna 5. The High Court and the Founders: an Unfaithful Servant 63 Professor Greg Craven 6. The 1897 Federal Convention Election: a Success or Failure? 93 Dr Kathleen Dermody 7. Federation Through the Eyes of a South Australian Model Parliament 121 Derek Drinkwater iii Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies* John Bannon s we approach the centenary of the establishment of our nation a number of fundamental Aquestions, not the least of which is whether we should become a republic, are under active debate. But after nearly one hundred years of experience there are some who believe that the most important question is whether our federal system is working and what changes if any should be made to it.