Aphids & Their Relatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kendal Kermes

K Kendal commonly known by that term in later medieval Europe: granum in Latin, grano in Italian, graine A woollen cloth.→ in French, grein in Flemish and German, and A kind of woollen cloth woven, or origi- grain in English. nally woven, in Kendal, a town in Westmorland Kermes-dyed textiles first appeared in the (now Cumbria); therefore called Kendal cloth, medieval British Isles in an urban context (prob- cloth kendalles; as an adjective it meant made of ably) in Anglo-Saxon Winchester and Anglo- Kendal cloth. The earliest references to the cloth Viking → York, but at this point kermes was date from legislation of 1390, and imply cloth of → → → confined to imported silk. Although wool the poorest→ quality (see →cloth: dimensions and textiles dyed with kermes are known from Roman weights). Gowns and hoods of Kendal are times, they do not reappear in northern Europe mentioned from c. 1443, from earlier Proceedings until the 11th century, becoming a major element in Chancery recorded→ in the reign of Elizabeth 1. in the medieval economy in the following centu- See also the naming of cloth. ries. Kermes has been discovered on ten samples Bibliography of woollen and silk textile from excavation in Kurath, H., Kuhn, S.M., Reidy, J. and Lewis, London at Swan Lane (13th century), Baynard’s R.E., ed., The Middle English Dictionary (Ann Castle (1325–50) and Custom House (1300–50). Arbor, MI: 1952–2001), s.v. Kendal. There is also a reference in the Customs Accounts of Hull, to cloth dyed with kermes coming into Elizabeth Coatsworth the port in the mid- to late 15th century. -

Aphis Fabae Scop.) to Field Beans ( Vicia Faba L.

ANALYSIS OF THE DAMAGE CAUSED BY THE BLACK BEAN APHID ( APHIS FABAE SCOP.) TO FIELD BEANS ( VICIA FABA L.) BY JESUS ANTONIO SALAZAR, ING. AGR. ( VENEZUELA ) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON OCTOBER 1976 IMPERIAL COLLEGE FIELD STATION, SILWOOD PARK, SUNNINGHILL, ASCOT, BERKSHIRE. 2 ABSTRACT The concept of the economic threshold and its importance in pest management programmes is analysed in Chapter I. The significance of plant responses or compensation in the insect-injury-yield relationship is also discussed. The amount of damage in terms of yield loss that results from aphid attack, is analysed by comparing the different components of yield in infested and uninfested plants. In the former, plants were infested at different stages of plant development. The results showed that seed weights, pod numbers and seed numbers in plants infested before the flowering period were significantly less than in plants infested during or after the period of flower setting. The growth pattern and growth analysis in infested and uninfested plants have shown that the rate of leaf production and dry matter production were also more affected when the infestations occurred at early stages of plant development. When field beans were infested during the flowering period and afterwards, the aphid feeding did not affect the rate of leaf and dry matter production. There is some evidence that the rate of leaf area production may increase following moderate aphid attack during this period. The relationship between timing of aphid migration from the wintering host and the stage of plant development are shown to be of considerable significance in determining the economic threshold for A. -

Garden Insects of North America: the Ultimate Guide to Backyard Bugs

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CONTENTS Preface 13 Acknowledgments 15 CHAPTER one Introduction to Garden Insects and Their Relatives 16 Arthropod Growth and Metamorphosis 18 Body Parts Useful in Diagnosing Garden Insect Orders 20 Arthropods 30 Identification of Immature Stages of Common Types of Plant Injuries Caused Arthropods 21 by Insects 31 Excreted and Secreted Products Useful in Plant Pathogens Transmitted by Insects Diagnosing Garden Arthropods and Mites 39 and Slugs 28 CHAPTER Two Insects That Chew on Leaves and Needles 40 Grasshoppers 42 Giant Silkworms/Royal Moths 78 Field Crickets 46 Cecropia Moth 78 Other Crickets and Katydids 46 Other Giant Silkworms/Royal Moths 78 Common (Northern) Walkingstick 50 Slug Caterpillars/Flannel Moths and Other Related Species 50 Stinging Caterpillars 84 European Earwig 52 Tussock Moths 86 Other Earwigs 52 Whitemarked Tussock Moth 86 Related and Similar Species 86 Cockroaches 54 Gypsy Moth 90 Imported Cabbageworm 56 Other Sulfur and White Butterflies 56 Woollybears 92 Swallowtails 58 Climbing Cutworms and Armyworms 94 Parsleyworm/Black Swallowtail 58 Variegated Cutworm 94 Other Swallowtails 60 Fall Armyworm 94 Beet Armyworm 96 Brushfooted Butterflies 62 Other Climbing Cutworms and Armyworms 96 Painted Lady/Thistle Caterpillar 62 Other Brushfooted Butterflies 62 Loopers 102 Cabbage Looper 102 Hornworms and Sphinx Moths 68 Other Common Garden Loopers 102 Tomato Hornworm and Tobacco Hornworm 68 Cankerworms, Inchworms, and Other Common Hornworms 70 Spanworms 104 Fall Cankerworm 104 Prominent Moths/Notodontids 74 Other Cankerworms, Inchworms, and Walnut Caterpillar 74 Spanworms 106 Other Notodontids/Prominent Moths on Shade Trees 74 Diamondback Moth 110 Skeletonizers 110 For general queries, contact [email protected] 01 GI pp001-039.indd 5 19/07/2017 21:16 © Copyright, Princeton University Press. -

(Pentatomidae) DISSERTATION Presented

Genome Evolution During Development of Symbiosis in Extracellular Mutualists of Stink Bugs (Pentatomidae) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alejandro Otero-Bravo Graduate Program in Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee: Zakee L. Sabree, Advisor Rachelle Adams Norman Johnson Laura Kubatko Copyrighted by Alejandro Otero-Bravo 2020 Abstract Nutritional symbioses between bacteria and insects are prevalent, diverse, and have allowed insects to expand their feeding strategies and niches. It has been well characterized that long-term insect-bacterial mutualisms cause genome reduction resulting in extremely small genomes, some even approaching sizes more similar to organelles than bacteria. While several symbioses have been described, each provides a limited view of a single or few stages of the process of reduction and the minority of these are of extracellular symbionts. This dissertation aims to address the knowledge gap in the genome evolution of extracellular insect symbionts using the stink bug – Pantoea system. Specifically, how do these symbionts genomes evolve and differ from their free- living or intracellular counterparts? In the introduction, we review the literature on extracellular symbionts of stink bugs and explore the characteristics of this system that make it valuable for the study of symbiosis. We find that stink bug symbiont genomes are very valuable for the study of genome evolution due not only to their biphasic lifestyle, but also to the degree of coevolution with their hosts. i In Chapter 1 we investigate one of the traits associated with genome reduction, high mutation rates, for Candidatus ‘Pantoea carbekii’ the symbiont of the economically important pest insect Halyomorpha halys, the brown marmorated stink bug, and evaluate its potential for elucidating host distribution, an analysis which has been successfully used with other intracellular symbionts. -

Zootaxa,Phylogeny and Higher Classification of the Scale Insects

Zootaxa 1668: 413–425 (2007) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2007 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Phylogeny and higher classification of the scale insects (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea)* P.J. GULLAN1 AND L.G. COOK2 1Department of Entomology, University of California, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] 2School of Integrative Biology, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland 4072, Australia. Email: [email protected] *In: Zhang, Z.-Q. & Shear, W.A. (Eds) (2007) Linnaeus Tercentenary: Progress in Invertebrate Taxonomy. Zootaxa, 1668, 1–766. Table of contents Abstract . .413 Introduction . .413 A review of archaeococcoid classification and relationships . 416 A review of neococcoid classification and relationships . .420 Future directions . .421 Acknowledgements . .422 References . .422 Abstract The superfamily Coccoidea contains nearly 8000 species of plant-feeding hemipterans comprising up to 32 families divided traditionally into two informal groups, the archaeococcoids and the neococcoids. The neococcoids form a mono- phyletic group supported by both morphological and genetic data. In contrast, the monophyly of the archaeococcoids is uncertain and the higher level ranks within it have been controversial, particularly since the late Professor Jan Koteja introduced his multi-family classification for scale insects in 1974. Recent phylogenetic studies using molecular and morphological data support the recognition of up to 15 extant families of archaeococcoids, including 11 families for the former Margarodidae sensu lato, vindicating Koteja’s views. Archaeococcoids are represented better in the fossil record than neococcoids, and have an adequate record through the Tertiary and Cretaceous but almost no putative coccoid fos- sils are known from earlier. -

Impact of Imidacloprid and Horticultural Oil on Nonâ•Fitarget

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2007 Impact of Imidacloprid and Horticultural Oil on Non–target Phytophagous and Transient Canopy Insects Associated with Eastern Hemlock, Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carrieré, in the Southern Appalachians Carla Irene Dilling University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Dilling, Carla Irene, "Impact of Imidacloprid and Horticultural Oil on Non–target Phytophagous and Transient Canopy Insects Associated with Eastern Hemlock, Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carrieré, in the Southern Appalachians. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/120 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Carla Irene Dilling entitled "Impact of Imidacloprid and Horticultural Oil on Non–target Phytophagous and Transient Canopy Insects Associated with Eastern Hemlock, Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carrieré, in the Southern Appalachians." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Entomology and Plant Pathology. Paris L. Lambdin, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Jerome Grant, Nathan Sanders, James Rhea, Nicole Labbé Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

Correlation of Stylet Activities by the Glassy-Winged Sharpshooter, Homalodisca Coagulata (Say), with Electrical Penetration Graph (EPG) Waveforms

ARTICLE IN PRESS Journal of Insect Physiology 52 (2006) 327–337 www.elsevier.com/locate/jinsphys Correlation of stylet activities by the glassy-winged sharpshooter, Homalodisca coagulata (Say), with electrical penetration graph (EPG) waveforms P. Houston Joosta, Elaine A. Backusb,Ã, David Morganc, Fengming Yand aDepartment of Entomology, University of Riverside, Riverside, CA 92521, USA bUSDA-ARS Crop Diseases, Pests and Genetics Research Unit, San Joaquin Valley Agricultural Sciences Center, 9611 South Riverbend Ave, Parlier, CA 93648, USA cCalifornia Department of Food and Agriculture, Mt. Rubidoux Field Station, 4500 Glenwood Dr., Bldg. E, Riverside, CA 92501, USA dCollege of Life Sciences, Peking Univerisity, Beijing, China Received 5 May 2005; received in revised form 29 November 2005; accepted 29 November 2005 Abstract Glassy-winged sharpshooter, Homalodisca coagulata (Say), is an efficient vector of Xylella fastidiosa (Xf), the causal bacterium of Pierce’s disease, and leaf scorch in almond and oleander. Acquisition and inoculation of Xf occur sometime during the process of stylet penetration into the plant. That process is most rigorously studied via electrical penetration graph (EPG) monitoring of insect feeding. This study provides part of the crucial biological meanings that define the waveforms of each new insect species recorded by EPG. By synchronizing AC EPG waveforms with high-magnification video of H. coagulata stylet penetration in artifical diet, we correlated stylet activities with three previously described EPG pathway waveforms, A1, B1 and B2, as well as one ingestion waveform, C. Waveform A1 occured at the beginning of stylet penetration. This waveform was correlated with salivary sheath trunk formation, repetitive stylet movements involving retraction of both maxillary stylets and one mandibular stylet, extension of the stylet fascicle, and the fluttering-like movements of the maxillary stylet tips. -

Twenty-Five Pests You Don't Want in Your Garden

Twenty-five Pests You Don’t Want in Your Garden Prepared by the PA IPM Program J. Kenneth Long, Jr. PA IPM Program Assistant (717) 772-5227 [email protected] Pest Pest Sheet Aphid 1 Asparagus Beetle 2 Bean Leaf Beetle 3 Cabbage Looper 4 Cabbage Maggot 5 Colorado Potato Beetle 6 Corn Earworm (Tomato Fruitworm) 7 Cutworm 8 Diamondback Moth 9 European Corn Borer 10 Flea Beetle 11 Imported Cabbageworm 12 Japanese Beetle 13 Mexican Bean Beetle 14 Northern Corn Rootworm 15 Potato Leafhopper 16 Slug 17 Spotted Cucumber Beetle (Southern Corn Rootworm) 18 Squash Bug 19 Squash Vine Borer 20 Stink Bug 21 Striped Cucumber Beetle 22 Tarnished Plant Bug 23 Tomato Hornworm 24 Wireworm 25 PA IPM Program Pest Sheet 1 Aphids Many species (Homoptera: Aphididae) (Origin: Native) Insect Description: 1 Adults: About /8” long; soft-bodied; light to dark green; may be winged or wingless. Cornicles, paired tubular structures on abdomen, are helpful in identification. Nymph: Daughters are born alive contain- ing partly formed daughters inside their bodies. (See life history below). Soybean Aphids Eggs: Laid in protected places only near the end of the growing season. Primary Host: Many vegetable crops. Life History: Females lay eggs near the end Damage: Adults and immatures suck sap from of the growing season in protected places on plants, reducing vigor and growth of plant. host plants. In spring, plump “stem Produce “honeydew” (sticky liquid) on which a mothers” emerge from these eggs, and give black fungus can grow. live birth to daughters, and theygive birth Management: Hide under leaves. -

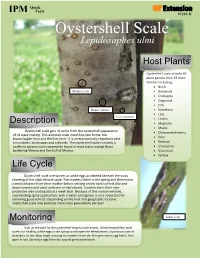

Oystershell Scale

Quick IPM Facts W289-R Oystershell Scale Lepidosaphes ulmi Host Plants Oystershell scale attacks 85 plant genera from 33 plant families including: • Birch Mother scale • Boxwood • Crabapple • Dogwood • Elm Dead crawlers • Hawthorn • Lilac Live crawlers • Linden Description • Magnolia • Maple Oystershell scale gets its name from the oystershell appearance • Ornamental cherry of its waxy coating. This armored scale insect has two forms: the • brown/apple form and the lilac form. It is an economically important pest Pear in nurseries, landscapes and orchards. The oystershell scale is mainly a • Redbud northern species and is commonly found in most states except those • Smoketree bordering Mexico and the Gulf of Mexico. • Viburnum • Willow Life Cycle Oystershell scale overwinter as white eggs protected beneath the waxy covering of the adult female scale. The crawlers hatch in the spring and then move a small distance from their mother before settling on the bark to feed (live and dead crawlers and adult scale are circled above). Crawlers form their own protective wax coating about a week later. Because of this narrow window, coordinating spray applications with crawler emergence is very important for achieving good control. Depending on the host and geographic location, oystershell scale may produce one to two generations per year. Monitoring Adult scale Look on the bark for the oystershell-shaped scale covers. Check beneath the scale covers for healthy, white eggs in the spring to estimate the effectiveness of previous control strategies. In late May, begin scouting for crawlers from the first-generation egg hatch, then again in late July when eggs from the second generation hatch. -

Diverse New Scale Insects (Hemiptera, Coccoidea) in Amber

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Number 3823, 80 pp. January 16, 2015 Diverse new scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) in amber from the Cretaceous and Eocene with a phylogenetic framework for fossil Coccoidea ISABELLE M. VEA1'2 AND DAVID A. GRIMALDI2 ABSTRACT Coccoids are abundant and diverse in most amber deposits around the world, but largely as macropterous males. Based on a study of male coccoids in Lebanese amber (Early Cretaceous), Burmese amber (Albian-Cenomanian), Cambay amber from western India (Early Eocene), and Baltic amber (mid-Eocene), 16 new species, 11 new genera, and three new families are added to the coccoid fossil record: Apticoccidae, n. fam., based on Apticoccus Koteja and Azar, and includ¬ ing two new species A.fortis, n. sp., and A. longitenuis, n. sp.; the monotypic family Hodgsonicoc- cidae, n. fam., including Hodgsonicoccus patefactus, n. gen., n. sp.; Kozariidae, n. fam., including Kozarius achronus, n. gen., n. sp., and K. perpetuus, n. sp.; the first occurrence of a Coccidae in Burmese amber, Rosahendersonia prisca, n. gen., n. sp.; the first fossil record of a Margarodidae sensu stricto, Heteromargarodes hukamsinghi, n. sp.; a peculiar Diaspididae in Indian amber, Nor- markicoccus cambayae, n. gen., n. sp.; a Pityococcidae from Baltic amber, Pityococcus monilifor- malis, n. sp., two Pseudococcidae in Lebanese and Burmese ambers, Williamsicoccus megalops, n. gen., n. sp., and Gilderius eukrinops, n. gen., n. sp.; an Early Cretaceous Weitschatidae, Pseudo- weitschatus audebertis, n. gen., n. sp.; four genera considered incertae sedis, Alacrena peculiaris, n. gen., n. sp., Magnilens glaesaria, n. gen., n. sp., and Pedicellicoccus marginatus, n. gen., n. sp., and Xiphos vani, n. -

Pest Alert: Brown Marmorated Stink Bug Halyomorpha Halys

OREGON DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FACT SHEETS AND PEST ALERTS Pest Alert: Brown Marmorated Stink Bug Halyomorpha halys Introduction Brown Marmorated Stink Bug The brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB), Halyomorpha adult nymph newly-hatched halys, is an Asian species first detected in North America nymphs in Pennsylvania in 1996, and in Oregon in 2004. BMSB has since been detected in 43 states. In Oregon it is es- tablished statewide, in the western region from Portland to Ashland, and in the north east to Hood River. More recently it has been found in coastal counties and is likely still expanding its range and increasing in abundance around Oregon. A threat to Oregon agriculture BMSB is a major agricultural pest in Asia, attacking many crops. It is a significant agricultural pest in the Mid-At- lantic states of the U.S., attacking tree fruits, peppers, tomatoes, corn, berries, grapes, soybeans, melons, and even damaging young trees by feeding through the bark. BMSB is known to feed on over 170 species of plants. The insect threatens an estimated $21 billion worth of crops in the United States alone. Some commercial agri- cultural damage by BMSB has been reported in Oregon. Some home gardeners have reported extensive damage to beans, cucumbers, raspberries, hops, and several species A brown marmorated stink bug feeding on a mature hazelnut. BMSB of ornamental plants. is able to feed on tree nuts through the shell using its long mouthparts. Damage to crops Stink bugs feed by inserting their long, straw-like mouth parts into plants and sucking out the liquid inside. -

PINE BARK ADELGID Hemiptera Adelgidae

PINE BARK ADELGID Hemiptera Adelgidae: Pineus strobi (Htg.) By Scott Salom and Eric Day DISTRIBUTION AND HOSTS: The pine bark adelgid is widely distributed in North America, occurring principally throughout the native range of eastern white pine. This insect is also found on Scots and Austrian pine. DESCRIPTION OF DAMAGE: Adelgids feed on tree trunks by sucking sap from the phloem tissue. Trunks of heavily infested trees often appear white- washed from the woolly masses these tiny insects secrete over themselves for protection. Small nursery stock, ornamental trees, and trees in parks can be heavily attacked. In severe cases, feeding can cause bud proliferation and give the tops of the trees a bushy “witches broom” appearance. However, if the trees are otherwise healthy, permanent damage should not result. In eastern white pine plantations of a forest setting, repeatedly infested mature pine trees apparently suffer no serious harm. IDENTIFICATION: Adelgids are similar to aphids, except they have shorter antennae and lack cornicles (or bumps) on their abdomen. They live under a woolly mass they secrete for protection. If this mass is pulled off the trunk, black teardrop- shaped insects with short legs are revealed. When populations are high, the woolly masses coalesce into one large mass on the Pine Bark Adelgid on white pine trunks. LIFE HISTORY: Overwintering immature adelgids will begin feeding during the first days of warm weather, and secrete woolly tufts. Once these insects develop to adults (April to May), egg laying begins. Eggs hatch into crawlers, which can move to other parts of the tree or be blown to other trees.