Philosophy of Biology”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Kinds and Concepts: a Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account

Natural Kinds and Concepts: A Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account Ingo Brigandt Abstract: In this chapter I lay out a notion of philosophical naturalism that aligns with prag- matism. It is developed and illustrated by a presentation of my views on natural kinds and my theory of concepts. Both accounts reflect a methodological naturalism and are defended not by way of metaphysical considerations, but in terms of their philosophical fruitfulness. A core theme is that the epistemic interests of scientists have to be taken into account by any natural- istic philosophy of science in general, and any account of natural kinds and scientific concepts in particular. I conclude with general methodological remarks on how to develop and defend philosophical notions without using intuitions. The central aim of this essay is to put forward a notion of naturalism that broadly aligns with pragmatism. I do so by outlining my views on natural kinds and my account of concepts, which I have defended in recent publications (Brigandt, 2009, 2010b). Philosophical accounts of both natural kinds and con- cepts are usually taken to be metaphysical endeavours, which attempt to develop a theory of the nature of natural kinds (as objectively existing entities of the world) or of the nature of concepts (as objectively existing mental entities). However, I shall argue that any account of natural kinds or concepts must an- swer to epistemological questions as well and will offer a simultaneously prag- matist and naturalistic defence of my views on natural kinds and concepts. Many philosophers conceive of naturalism as a primarily metaphysical doc- trine, such as a commitment to a physicalist ontology or the idea that humans and their intellectual and moral capacities are a part of nature. -

History of Philosophymetaphysics & Epistem Ology Norm Ative

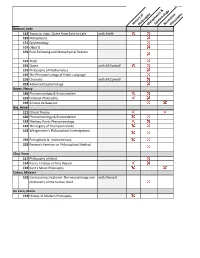

HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Azzouni, Jody 114 Topics in Logic: Quine from Early to Late with Smith 120 Metaphysics 131 Epistemology 191 Objects 191 Rule-Following and Metaphysical Realism 191 Truth 191 Quine with McConnell 191 Philosophy of Mathematics 192 The Phenomenology of Public Language 195 Chomsky with McConnell 292 Advanced Epistemology Bauer, Nancy 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 191 Feminist Philosophy 192 Simone de Beauvoir Baz, Avner 121 Ethical Theory 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 192 Merleau Ponty Phenomenology 192 The Legacy of Thompson Clarke 192 Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations 292 Perceptions & Indeterminacy 292 Research Seminar on Philosophical Method Choi, Yoon 117 Philosophy of Mind 164 Kant's Critique of Pure Reason 192 Kant's Moral Philosophy Cohen, Michael 192 Conciousness Explored: The neurobiology and with Dennett philosophy of the human mind De Caro, Mario 152 History of Modern Philosophy De HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Car 191 Nature & Norms 191 Free Will & Moral Responsibility Denby, David 133 Philosophy of Language 152 History of Modern Philosophy 191 History of Analytic Philosophy 191 Topics in Metaphysics 195 The Philosophy of David Lewis Dennett, Dan 191 Foundations of Cognitive Science 192 Artificial Agents & Autonomy with Scheutz 192 Cultural Evolution-Is it Darwinian 192 Topics in Philosophy of Biology: The Boundaries with Forber of Darwinian Theory 192 Evolving Minds: From Bacteria to Bach 192 Conciousness -

Development, Evolution, and Adaptation Author(S): Kim Sterelny Source: Philosophy of Science, Vol

Philosophy of Science Association Development, Evolution, and Adaptation Author(s): Kim Sterelny Source: Philosophy of Science, Vol. 67, Supplement. Proceedings of the 1998 Biennial Meetings of the Philosophy of Science Association. Part II: Symposia Papers (Sep., 2000), pp. S369-S387 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Philosophy of Science Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/188681 Accessed: 03/03/2010 17:09 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Philosophy of Science Association and The University of Chicago Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Philosophy of Science. -

Philosophical Perspectives on Evolutionary Theory

Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia, 92: 461–464, 2009 Philosophical perspectives on Evolutionary Theory A Tapper Centre for Applied Ethics & Philosophy, Curtin University of Technology, Bentley, WA [email protected] Manuscript received December 2009; accepted February 2010 Abstract Discussion of Darwinian evolutionary theory by philosophers has gone through a number of historical phases, from indifference (in the first hundred years), to criticism (in the 1960s and 70s), to enthusiasm and expansionism (since about 1980). This paper documents these phases and speculates about what, philosophically speaking, underlies them. It concludes with some comments on the present state of the evolutionary debate, where rapid and important changes within evolutionary theory may be passing by unnoticed by philosophers. Keywords: Darwinism, evolutionary theory, philosophy of biology; evolution. Introduction author. Biologists such as Richard Dawkins, Stephen Jay Gould, Steve Jones and Simon Conway Morris are Darwin once said that he had no aptitude for prominent. So also are historians of science, such as Peter philosophy: “My power to follow a long and purely Bowler, Janet Browne, Adrian Desmond and James R. abstract train of thought is very limited; I should, Moore. Equally likely, however, one might be introduced moreover, never have succeeded with metaphysics or to evolutionary theory by a philosopher of biology, for mathematics” (Darwin 1958). This was not false modesty; example Michael Ruse, David Hull or Kim Sterelny. (For -

The Philosophy of Biology Edited by David L

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85128-2 - The Cambridge Companion to the Philosophy of Biology Edited by David L. Hull and Michael Ruse Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to THE PHILOSOPHY OF BIOLOGY The philosophy of biology is one of the most exciting new areas in the field of philosophy and one that is attracting much attention from working scientists. This Companion, edited by two of the founders of the field, includes newly commissioned essays by senior scholars and by up-and- coming younger scholars who collectively examine the main areas of the subject – the nature of evolutionary theory, classification, teleology and function, ecology, and the prob- lematic relationship between biology and religion, among other topics. Up-to-date and comprehensive in its coverage, this unique volume will be of interest not only to professional philosophers but also to students in the humanities and researchers in the life sciences and related areas of inquiry. David L. Hull is an emeritus professor of philosophy at Northwestern University. The author of numerous books and articles on topics in systematics, evolutionary theory, philosophy of biology, and naturalized epistemology, he is a recipient of a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship and is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Michael Ruse is professor of philosophy at Florida State University. He is the author of many books on evolutionary biology, including Can a Darwinian Be a Christian? and Darwinism and Its Discontents, both published by Cam- bridge University Press. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, he has appeared on television and radio, and he contributes regularly to popular media such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Playboy magazine. -

Sex and Death: an Introduction to Philosophy of Biology Pdf Free

SEX AND DEATH: AN INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY OF BIOLOGY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kim Sterelny,Paul Griffiths | 416 pages | 15 Jun 1999 | The University of Chicago Press | 9780226773049 | English | Chicago, IL, United States Sex and Death: An Introduction to Philosophy of Biology PDF Book Beyond the Modular Emotions Harriet S. The Nature of Species 9. Reduction by Degrees? Griffiths present both the science and the philosophical context necessary for a critical understanding of the most exciting debates shaping biology today. Overall I wouldn't say it is a bad book, and certainly gives tons of information about philosophy of biology, but I think I tried to bite off more than I can chew. Enlightenment, Compassion and Bioscientific Phenomena 4. Replicators and Interactors 3. How can I wanted to dig deeper into evolutionary biology, but I had two problems. There are few things I got from it. Privacy Policy Terms of Use. Other editions. Is the history of life a series of accidents or a drama scripted by selfish genes? However, for technical advancements to make real impacts both on patient health and genuine scientific understanding, quite a number of lingering challenges facing the entire spectrum from protein biology all the way to randomized controlled trials should start to be overcome. Oceanography and Marine Biology. Crandall , Norman C. Reduction in General Philosophy of Science. Images Additional images. Informed answers to questions like these, critical to our understanding of ourselves and the world around us, require both a knowledge o Is the history of life a series of accidents or a drama scripted by selfish genes? The Balance of Nature In this accessible introduction to philosophy of biology, Kim Sterelny and Paul E. -

May 03 CI.Qxd

Philosophy of Chemistry by Eric Scerri Of course, the field of compu- hen I push my hand down onto my desk it tational quantum chemistry, does not generally pass through the which Dirac and other pioneers Wwooden surface. Why not? From the per- of quantum mechanics inadver- spective of physics perhaps it ought to, since we are tently started, has been increas- told that the atoms that make up all materials consist ingly fruitful in modern mostly of empty space. Here is a similar question that chemistry. But this activity has is put in a more sophisticated fashion. In modern certainly not replaced the kind of physics any body is described as a superposition of chemistry in which most practitioners are engaged. many wavefunctions, all of which stretch out to infin- Indeed, chemists far outnumber scientists in all other ity in principle. How is it then that the person I am fields of science. According to some indicators, such as talking to across my desk appears to be located in one the numbers of articles published per year, chemistry particular place? may even outnumber all the other fields of science put together. If there is any sense in which chemistry can The general answer to both such questions is that be said to have been reduced then it can equally be although the physics of microscopic objects essen- said to be in a high state of "oxidation" regarding cur- tially governs all of matter, one must also appeal to rent academic and industrial productivity. the laws of chemistry, material science, biology, and Starting in the early 1990s a group of philosophers other sciences. -

Bridging the Philosophies of Biology and Chemistry

CALL FOR PAPERS First International Conference on Bridging the Philosophies of Biology and Chemistry 25-27 June 2019 University of Paris Diderot, France Extended Deadline for Abstract Submission: 28 February 2019 The aim of this conference is to bring philosophers of biology and philosophers of chemistry together and to explore common grounds and topics of interest. We particularly welcome papers on (1) the philosophy of interdisciplinary fields between biology and chemistry; (2) historical case studies on the disciplinary divergence and convergence of biology and chemistry; and (3) the similarities and differences between philosophical approaches to biology and chemistry. Philosophy is broadly construed and includes epistemological, methodological, ontological, metaphysical, ethical, political, and legal issues of science. For a detailed description of possible topics, please see below and visit the conference website http://www.sphere.univ-paris-diderot.fr/spip.php?article2228&lang=en Instructions for Abstract Submission Submit a Word file including author name(s), affiliation, paper title, and an abstract of maximum 500 words by 28 February 2019 to Jean-Pierre Llored ([email protected]) . Registration If you are interested in participating, please register by sending an e-mail to Jean-Pierre Llored ([email protected]) before 30 April 2019. Venue Room 454A, Building Condorcet, University Paris Diderot, 4, rue Elsa Morante, 75013 Paris, France Sponsors CNRS; Laboratory SPHERE, Laboratory LIED, and Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Paris Diderot; Fondation de la Maison de la Chimie; Free University of Brussels; University of Lille Organizers Cécilia Bognon, Quentin Hiernaux, Jean-Pierre Llored, Joachim Schummer First international Conference on Bridging the Philosophies of Biology and Chemistry 25-27 June 2019, University of Paris Diderot, France Description Background For much of the twentieth century, philosophy of science had almost exclusively been focused on physics and mathematics. -

Rethinking the Pragmatic Systems Biology and Systems-Theoretical Biology Divide: Toward a Complexity-Inspired Epistemology of Systems Biomedicine T

Medical Hypotheses 131 (2019) 109316 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Medical Hypotheses journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mehy Rethinking the pragmatic systems biology and systems-theoretical biology divide: Toward a complexity-inspired epistemology of systems biomedicine T Srdjan Kesić Department of Neurophysiology, Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković”, University of Belgrade, Despot Stefan Blvd. 142, 11060 Belgrade, Serbia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: This paper examines some methodological and epistemological issues underlying the ongoing “artificial” divide Systems biology between pragmatic-systems biology and systems-theoretical biology. The pragmatic systems view of biology has Cybernetics encountered problems and constraints on its explanatory power because pragmatic systems biologists still tend Second-order cybernetics to view systems as mere collections of parts, not as “emergent realities” produced by adaptive interactions Complexity between the constituting components. As such, they are incapable of characterizing the higher-level biological Complex biological systems phenomena adequately. The attempts of systems-theoretical biologists to explain these “emergent realities” Epistemology of complexity using mathematics also fail to produce satisfactory results. Given the increasing strategic importance of systems biology, both from theoretical and research perspectives, we suggest that additional epistemological and methodological insights into the possibility of further integration between -

Function Without Purpose

FUNCTION WITHOUT PURPOSE: The Uses of Causal Role Function in Evolutionary Biology This document is not a reproduction of the original published article. It is a facsimile of the text, arranged to have the same pagination as the published version. Amundson, Ron and Lander, George V. Function without purpose: The uses of causal role function in evolutionary biology. In: Biology and Philosophy v. 9, 1994, pp. 443-469 Ron Amundson Department of Philosophy University of Hawaii at Hilo Hilo, HI 96720 [email protected] George V. Lauder School of Biological Sciences University of California Irvine, CA 92717 [email protected] ABSTRACT Philosophers of evolutionary biology favor the so-called "etiological concept" of function according to which the function of a trait is its evolutionary purpose, defined as the effect for which that trait was favored by natural selection. We term this the selected effect (SE) analysis of function. An alternative account of function was introduced by Robert Cummins in a non-evolutionary and non-purposive context. Cummins's account has received attention but little support from philosophers of biology. This paper will show that a similar non-purposive concept of function, which we term causal role (CR) function, is crucial to certain research programs in evolutionary biology, and that philosophical criticisms of Cummins's concept are ineffective in this scientific context. Specifically, we demonstrate that CR functions are a vital and ineliminable part of research in comparative and functional anatomy, and that biological categories used by anatomists are not defined by the application of SE functional analysis. -

Preprint Forthcoming in Philosophy and Phenomenological Research Naturalism, Reduction and Normativity: Pressing from Below

Preprint Forthcoming in Philosophy and Phenomenological Research Naturalism, Reduction and Normativity: Pressing from Below JOHN F. POST Vanderbilt University David Papineau’s model of scientific reduction, contrary to his intent, appears to enable a naturalist realist account of the primitive normativity involved in a biological adaptation’s being “for” this or that (say the eye’s being for seeing). By disabling the crucial anti-naturalist arguments against any such reduction, his model would support a cognitivist semantics for normative claims like “The heart is for pumping blood, and defective if it doesn’t.” No moral claim would follow, certainly. Nonetheless, by thus “pressing from below” we may learn something about moral normativity. For instance, suppose non-cognitivists like Mackie are right that the semantics of normative claims should be “unified”: if the semantics of moral claims is non-cognitivist, so too is that of all normative claims. Then, assuming that a naturalist reduction does yield a sound cognitivist account of the primitive normativity, it would follow that our semantics of moral claims is cognitivist as well. I. Introduction In “The Status of Teleosemantics, Or How to Stop Worrying About Swampman” David Papineau (2001) defends teleosemantics against objections advanced by David Braddon-Mitchell and Frank Jackson (1997). Papineau’s defense succeeds, I believe, and yet it poses a problem for what he says about normativity: Wherever the normativity of content comes from, it can’t be from biology, since biology deals in facts, not prescriptions. It has always mystified me why anybody should think that biology helps with normativity (Papineau 2001, 280). -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Philip Stuart Kitcher February 2018 Date of Birth: February 20 1947 Place of Birth: London, England Citizenship: British by origin, naturalized American citizen (May 1995). Home address: 454 Riverside Drive, Apt. 6B, New York, NY 10027 Home phone: (212)-662-5812 Office phone: (212)-854-4884, (212)-854-3196 (department) E-mail: [email protected] Higher Education Christ's College, Cambridge; 1966-1969, B.A. 1969, (M.A. 1996). (First class honours in Mathematics/History and Philosophy of Science) Princeton University; 1969-1973; Ph.D. 1974 (Department of Philosophy/Program in History and Philosophy of Science) Honorary Degree Doctor, honoris causa Erasmus University Rotterdam November 2013 (on the occasion of the University centennial; awarded for “outstanding contributions to philosophy of science”) Honors and Awards Henry Schuman Prize (awarded by the History of Science Society, for the best essay by a graduate student), 1971 University of Vermont Summer Research Grant, 1975 University of Vermont Summer Research Grant, 1979 NEH Summer Research Grant, 1979 ACLS Study Fellowship, 1981-82 University of Vermont Distinguished Scholar in Humanities and Social Sciences, 1983 NEH Fellowship for College Teachers, 1983-84 NEH Grant for Institute to Investigate a Possible New Consensus in Philosophy of Science (Joint Principal Investigator with C. Wade Savage) 1 Imre Lakatos Award (co-winner with Michael Friedman) 1986. Awarded for Vaulting Ambition. NEH Fellowship for University Teachers 1988-89 (declined) John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship 1988-89 Principal Investigator, five-year NSF Research and Training Grant for the development of a Science Studies Center at UCSD. (Awarded Fall 1990). Revelle College (UCSD) Distinguished Teaching Award, 1990.