Toward a Pragmatist Philosophy of Science *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Kinds and Concepts: a Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account

Natural Kinds and Concepts: A Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account Ingo Brigandt Abstract: In this chapter I lay out a notion of philosophical naturalism that aligns with prag- matism. It is developed and illustrated by a presentation of my views on natural kinds and my theory of concepts. Both accounts reflect a methodological naturalism and are defended not by way of metaphysical considerations, but in terms of their philosophical fruitfulness. A core theme is that the epistemic interests of scientists have to be taken into account by any natural- istic philosophy of science in general, and any account of natural kinds and scientific concepts in particular. I conclude with general methodological remarks on how to develop and defend philosophical notions without using intuitions. The central aim of this essay is to put forward a notion of naturalism that broadly aligns with pragmatism. I do so by outlining my views on natural kinds and my account of concepts, which I have defended in recent publications (Brigandt, 2009, 2010b). Philosophical accounts of both natural kinds and con- cepts are usually taken to be metaphysical endeavours, which attempt to develop a theory of the nature of natural kinds (as objectively existing entities of the world) or of the nature of concepts (as objectively existing mental entities). However, I shall argue that any account of natural kinds or concepts must an- swer to epistemological questions as well and will offer a simultaneously prag- matist and naturalistic defence of my views on natural kinds and concepts. Many philosophers conceive of naturalism as a primarily metaphysical doc- trine, such as a commitment to a physicalist ontology or the idea that humans and their intellectual and moral capacities are a part of nature. -

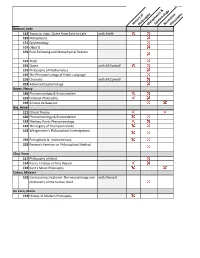

History of Philosophymetaphysics & Epistem Ology Norm Ative

HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Azzouni, Jody 114 Topics in Logic: Quine from Early to Late with Smith 120 Metaphysics 131 Epistemology 191 Objects 191 Rule-Following and Metaphysical Realism 191 Truth 191 Quine with McConnell 191 Philosophy of Mathematics 192 The Phenomenology of Public Language 195 Chomsky with McConnell 292 Advanced Epistemology Bauer, Nancy 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 191 Feminist Philosophy 192 Simone de Beauvoir Baz, Avner 121 Ethical Theory 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 192 Merleau Ponty Phenomenology 192 The Legacy of Thompson Clarke 192 Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations 292 Perceptions & Indeterminacy 292 Research Seminar on Philosophical Method Choi, Yoon 117 Philosophy of Mind 164 Kant's Critique of Pure Reason 192 Kant's Moral Philosophy Cohen, Michael 192 Conciousness Explored: The neurobiology and with Dennett philosophy of the human mind De Caro, Mario 152 History of Modern Philosophy De HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Car 191 Nature & Norms 191 Free Will & Moral Responsibility Denby, David 133 Philosophy of Language 152 History of Modern Philosophy 191 History of Analytic Philosophy 191 Topics in Metaphysics 195 The Philosophy of David Lewis Dennett, Dan 191 Foundations of Cognitive Science 192 Artificial Agents & Autonomy with Scheutz 192 Cultural Evolution-Is it Darwinian 192 Topics in Philosophy of Biology: The Boundaries with Forber of Darwinian Theory 192 Evolving Minds: From Bacteria to Bach 192 Conciousness -

What Is That Thing Called Philosophy of Technology? - R

HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY – Vol. IV - What Is That Thing Called Philosophy of Technology? - R. J. Gómez WHAT IS THAT THING CALLED PHILOSOPHY OF TECHNOLOGY? R. J. Gómez Department of Philosophy. California State University (LA). USA Keywords: Adorno, Aristotle, Bunge, Ellul, Feenberg, Habermas, Heidegger, Horkheimer, Jonas, Latour, Marcuse, Mumford, Naess, Shrader-Frechette, artifact, assessment, determinism, ecosophy, ends, enlightenment, efficiency, epistemology, enframing, ideology, life-form, megamachine, metaphysics, method, naturalistic, fallacy, new, ethics, progress, rationality, rule, science, techno-philosophy Contents 1. Introduction 2. Locating technology with respect to science 2.1. Structure and Content 2.2. Method 2.3. Aim 2.4. Pattern of Change 3. Locating philosophy of technology 4. Early philosophies of technology 4.1. Aristotelianism 4.2. Technological Pessimism 4.3. Technological Optimism 4.4. Heidegger’s Existentialism and the Essence of Technology 4.5. Mumford’s Megamachinism 4.6. Neomarxism 4.6.1. Adorno-Horkheimer 4.6.2. Marcuse 4.6.3. Habermas 5. Recent philosophies of technology 5.1. L. Winner 5.2. A. Feenberg 5.3. EcosophyUNESCO – EOLSS 6. Technology and values 6.1. Shrader-Frechette Claims 6.2. H Jonas 7. Conclusions SAMPLE CHAPTERS Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary A philosophy of technology is mainly a critical reflection on technology from the point of view of the main chapters of philosophy, e.g., metaphysics, epistemology and ethics. Technology has had a fast development since the middle of the 20th century , especially ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY – Vol. IV - What Is That Thing Called Philosophy of Technology? - R. -

Kant's Definition of Science in the Architectonic of Pure Reason And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Research Information System University of Turin 372DOI 10.1515/kant-2014-0016Gabriele Gava KANT-STUDIEN 2014; 105(3): 372–393 Gabriele Gava Kant’s Definition of Science in the Architectonic of Pure Reason and the Essential Ends of Reason Abstract: The paper analyses the definition of science as an architectonic unity, which Kant gives in the Architectonic of Pure Reason. I will show how this defini- tion is problematic, insofar as it is affected by the various ways in which the rela- tionship of reason to ends is discussed in this chapter of the Critique of Pure Rea- son. Kant sometimes claims that architectonic unity is only obtainable thanks to an actual reference to the essential practical ends of human reason, but he also identifies disciplines that do not make this reference as scientific. In order to find a solution to this apparent contradiction, I will first present Kant’s distinction be- tween a scholastic and a cosmic concept of philosophy. This distinction expresses Kant’s foreshadowing of his later insistence on the priority of practical philos- ophy within a true system of philosophy. Then, I will present a related distinction between technical and architectonic unity and show how Kant seems to use two different conceptions of science, one simply attributing systematic unity to science, the other claiming that science should consider the essential practical ends of human beings. I will propose a solution to this problem by arguing that, if we give a closer look to Kant’s claims, the unity of scientific disciplines can be considered architectonic without taking into consideration the essential practi- cal ends of human reason. -

472 Philip Kitcher Preludes to Pragmatism

Philosophy in Review XXXIII (2013), no. 6 Philip Kitcher Preludes to Pragmatism: Toward a Reconstruction of Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2012. 464 pages $45.00 (cloth ISBN 978–0–19–989955–5) This book collects seventeen of Philip Kitcher’s essays from the past two decades. All but two have been published elsewhere, and several are quite well-known. ‘The Naturalists Return’, for example, appeared in Philosophical Review’s 1992 centennial issue, and is a staple of reading lists in epistemology and the philosophy of science. But the book frames these essays in a valuable new way. In the period from which these essays are drawn, Kitcher moved steadily toward an embrace of pragmatism, and the book presents them as milestones in this development: tentative applications of pragmatist ideas to a range of topics. Hence the word ‘prelude’. Kitcher says that he is not yet ready to present a ‘fully developed pragmatic naturalist position’ and that he is merely giving ‘pointers’ toward such a position (xvi-xvii). But this modesty does not do justice to the sophistication of his pragmatism. Preludes to Pragmatism is a rich and rewarding book that will interest philosophers of many different stripes. It may also prove to be an important contribution to the history of pragmatism. The book’s lengthy introduction puts the essays in context. Kitcher seems surprised to have wound up a pragmatist. ‘Two decades ago’, he writes, ‘I would have seen the three canonical pragmatists—Peirce, James, and Dewey—as well-intentioned but benighted, laboring with crude tools to develop ideas that were far more rigorously and exactly shaped by… what is (unfortunately) known as “analytic” philosophy’ (xi). -

PRAGMATISM and ITS IMPLICATIONS: Pragmatism Is A

PRAGMATISM AND ITS IMPLICATIONS: Pragmatism is a philosophy that has had its chief development in the United States, and it bears many of the characteristics of life on the American continent.. It is connected chiefly with the names of William James (1842-1910) and John Dewey. It has appeared under various names, the most prominent being pragmatism, instrumentalism, and experimentalism. While it has had its main development in America, similar ideas have been set forth in England by Arthur Balfour and by F. C. S. Schiller, and in Germany by Hans Vaihingen. WHAT PRAGMATISM IS Pragmatism is an attitude, a method, and a philosophy which places emphasis upon the practical and the useful or upon that which has satisfactory consequences. The term pragmatism comes from a Greek word pragma, meaning "a thing done," a fact, that which is practical or matter-of-fact. Pragmatism uses the practical consequences of ideas and beliefs as a standard for determining their value and truth. William James defined pragmatism as "the attitude of looking away from first things, principles, 'categories,' supposed necessities; and of looking towards last things, fruits, consequences, facts." Pragmatism places greater emphasis upon method and attitude than upon a system of philosophical doctrine. It is the method of experimental inquiry carried into all realms of human experience. Pragmatism is the modern scientific method taken as the basis of a philosophy. Its affinity is with the biological and social sciences, however, rather than with the mathematical and physical sciences. The pragmatists are critical of the systems of philosophy as set forth in the past. -

Philosophy of Science Reading List

Philosophy of Science Area Comprehensive Exam Reading List Revised September 2011 Exam Format: Students will have four hours to write answers to four questions, chosen from a list of approximately 20-30 questions organized according to topic: I. General Philosophy of Science II. History of Philosophy of Science III. Special Topics a. Philosophy of Physics b. Philosophy of Biology c. Philosophy of Mind / Cognitive Science d. Logic and Foundations of Mathematics Students are required to answer a total of three questions from sections I and II (at least one from each section), and one question from section III. For each section, we have provided a list of core readings—mostly journal articles and book chapters—that are representative of the material with which we expect you to be familiar. Many of these readings will already be familiar to you from your coursework and other reading. Use this as a guide to filling in areas in which you are less well- prepared. Please note, however, that these readings do not constitute necessary or sufficient background to pass the comp. The Philosophy of Science area committee assumes that anyone who plans to write this exam has a good general background in the area acquired through previous coursework and independent reading. Some anthologies There are several good anthologies of Philosophy of Science that will be useful for further background (many of the articles listed below are anthologized; references included in the list below). Richard Boyd, Philip Gasper, and J.D. Trout, eds., The Philosophy of Science (MIT Press, 991). Martin Curd and J. -

Kitcher's Modest Realism: the Reconceptualization of Scientific

1 KITCHER’S MODEST REALISM: THE RECONCEPTUALIZATION OF SCIENTIFIC OBJECTIVITY Antonio Diéguez Forthcoming in W. J. González (ed.), Scientific Realism and Democratic Society: The Philosophy of Philip Kitcher , “Poznan Studies in the Philosophy of the Sciences and the Humanities”, Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2010. Abstract In Science, Truth and Democracy , Kitcher moderates the strongest ontological realist thesis he defended in The Advancement of Science , with the aim of making compatible the correspondence theory of truth with conceptual relativity. However, it is not clear that both things could be harmonized. If our knowledge of the world is mediated by our categories and concepts; if the selection of these categories and concepts may vary according to our interests, and they are not the consequence of the existence of certain supposed natural kinds or some intrinsic structure of the world, it is very problematic to establish what our true statements correspond to. This paper analyzes the transformation in Kitcher’s realism and expounds the main difficulties in this project. Finally, a modality of moderate ontological realism will be proposed that, despite of keeping the sprit of the conceptual relativity, is strong enough to support the correspondence theory of truth. KEY WORDS MODEST REALISM, CONCEPTUAL RELATIVITY, CORRESPONDENCE THEORY OF TRUTH The last two decades have been a period of deep changes in the realm of the philosophy of science. Not only its hegemony among meta-scientific disciplines has been challenged by the sociology of science and, in general, by the social studies of science, but the objective that guided it from the beginning of its academic institutionalization with the Vienna Circle in the 1930’s —i. -

Foundations of Nursing Science 9781284041347 CH01.Indd Page 2 10/23/13 10:44 AM Ff-446 /207/JB00090/Work/Indd

9781284041347_CH01.indd Page 1 10/23/13 10:44 AM ff-446 /207/JB00090/work/indd © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION PART 1 Foundations of Nursing Science 9781284041347_CH01.indd Page 2 10/23/13 10:44 AM ff-446 /207/JB00090/work/indd © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION 9781284041347_CH01.indd Page 3 10/23/13 10:44 AM ff-446 /207/JB00090/work/indd © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CHAPTER Philosophy of Science: An Introduction 1 E. Carol Polifroni Introduction A philosophy of science is a perspective—a lens, a way one views the world, and, in the case of advanced practice nurses, the viewpoint the nurse acts from in every encounter with a patient, family, or group. A person’s philosophy of science cre- ates the frame on a picture—a message that becomes a paradigm and a point of reference. Each individual’s philosophy of science will permit some things to be seen and cause others to be blocked. It allows people to be open to some thoughts and potentially keeps them closed to others. A philosophy will deem some ideas correct, others inconsistent, and some simply wrong. While philosophy of sci- ence is not meant to be viewed as a black or white proposition, it does provide perspectives that include some ideas and thoughts and, therefore, it must neces- sarily exclude others. The important key is to ensure that the ideas and thoughts within a given philosophy remain consistent with one another, rather than being in opposition. -

Redalyc.Kitcher on Well-Ordered Science: Should Science Be

THEORIA. Revista de Teoría, Historia y Fundamentos de la Ciencia ISSN: 0495-4548 [email protected] Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea España KEREN, ARNON Kitcher on Well-Ordered Science: Should Science Be Measured against the Outcomes of Ideal Democratic Deliberation? THEORIA. Revista de Teoría, Historia y Fundamentos de la Ciencia, vol. 28, núm. 2, 2013, pp. 233- 244 Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea Donostia-San Sebastián, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=339730822003 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Kitcher on Well-Ordered Science: Should Science Be Measured against the Outcomes of Ideal Democratic Deliberation? * Arnon KEREN Received: 02.10.2012 Final version: 25.02.2013 BIBLID [0495-4548 (2013) 28: 77; pp. 233-244] ABSTRACT: What should the goals of scientific inquiry be? What questions should scientists investigate, and how should our resources be distributed between different lines of investigation? Philip Kitcher has suggested that we should answer these questions by appealing to an ideal based on the consideration of hypothetical democratic deliberations under ideal circumstances. This paper examines possible arguments that might support acceptance of this ideal for science, and argues that neither the arguments -

Philosophy Upside Down?

Philosophy Upside Down? Peter Baumann published in: Metaphilosophy 44, no. 5 (October 2013): 579-588. The definitive version is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/meta.12046/abstract Abstract Philip Kitcher recently argued for a reconstruction in philosophy. According to him, the contemporary mainstream of philosophy (in the English speaking world, at least) has deteriorated into something which is of relevance only to a few specialists who communicate with each other in a language nobody else understands. Kitcher proposes to reconstruct philosophy along two axes: a knowledge axis (with a focus on the sciences) and a value axis. I discuss Kitcher’s diagnosis as well as his proposal of a therapy. I argue that there are problems with both. I end with an alternative view of what some core problems of the profession currently are. KEYWORDS: applied philosophy; Philip Kitcher; pragmatism; reconstruction in philosophy; scholasticism. In a recent contribution to Metaphilosophy Philip Kitcher argues that there is something deeply wrong with contemporary mainstream anglophone philosophy and that we should “reconstruct” philosophy “inside out” (see Kitcher 2011).1 Kitcher expresses some caution with respect to both his diagnosis and the proposed therapy (see 249); he is happy to admit the vagueness of some of his remarks (see 254; see, e.g., some passages on 252 and 254) and even remarks that much “of what I have said is probably crude, simplistic, and wrong” (258). He continues: “Yet I don’t think that the errors and the need for refinement matter to my plea for philosophical redirection.” (258). I think we should follow Kitcher’s lead here and not worry too much about the details (it is not clear anyway which of the more detailed claims Kitcher is more committed to and which less). -

Pragmatic Theory of Truth” by William James

“Pragmatic Theory of Truth” by William James William James, NIH About the author. William James (1842-1910) is perhaps the most widely known of the founders of pragmatism. Historically, his Principles of Psychology was the first unification of psychology as a philosophical science. As a teacher of philosophy, he was a colleague of both Josiah Royce and George Santayana. Once Royce was asked to substitute teach for James in James’ Harvard philosophy class which, at the time, happened to be studying Royce’s text. Supposedly, as Royce picked up James’ copy of his text in the lecture hall, he hesitated briefly, and then noted to the class that James had written in the margin of the day’s reading, “ Damn fool!” About the work. In his Pragmatism,1 William James characterizes truth in terms of usefulness and acceptance. In general, on his view, truth is found by attending to the practical consequences of ideas. To say that truth is mere agreement of ideas with matters of fact, according to James, is incomplete, and to say that truth is captured by coherence is not to dis- tinguish it from a consistent falsity. In a genuine sense, James believes we construct truth in the process of successful living in the world: truth is in 1. William James. Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking. New York: Longman Green and Co., 1907. 1 “Pragmatic Theory of Truth” by William James no sense absolute. Beliefs are considered to be true if and only if they are useful and can be practically applied.