Darwin and His Finches: the Evolution of a Legend

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trichomonosis in Garden Birds

Trichomonosis in Garden Birds Agent Trichomonas gallinae is a single-celled protozoan parasite that can cause a disease known as trichomonosis in garden birds. Species affected Trichomonosis is known to affect pigeons and doves in the UK, including woodpigeons (Columba palumbus), feral pigeons (Columbia livia)and collared doves (Streptopelia decaocto) that routinely visit garden feeders, and the endangered turtle dove (Streptopelia turtur), which sometimes feed on food spills from bird tables in rural areas. It can also affect birds of prey that feed on other birds that are infected with the parasite. The common name for the disease in pigeons and doves is “canker” and in birds of prey the disease is also known as “frounce”. Trichomonosis was first seen in British finch species in summer 2005 with subsequent epidemic spread throughout Great Britain and across Europe. Whilst greenfinch (Chloris chloris) and chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs) are the species that have been most frequently affected by this emerging infectious disease, many other garden bird species which are gregarious and feed on seed, including the house sparrow (Passer domesticus), siskin (Carduelis spinus), goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) and bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula), are susceptible to the condition. Other garden bird species that typically feed on invertebrates, such as blackbird (Turdus merula) and dunnock (Prunella modularis) are also susceptible: investigations indicate they are not commonly affected but that this tends to be observed in gardens where outbreaks of disease involving large numbers of finches occur. Pathology Trichomonas gallinae typically causes disease at the back of the throat and in the gullet. Signs of disease In addition to showing signs of general illness, for example lethargy and fluffed-up plumage, affected birds may drool saliva, regurgitate food, have difficulty in swallowing or show laboured breathing. -

Biogeography, Overview

BIOGEOGRAPHY, OVERVIEW Mark V. Lomolino Oklahoma Biological Survey, Oklahoma Natural Heritage Inventory, and University of Oklahoma I. Introduction BIOGEOGRAPHY HAS A LONG AND DISTIN- II. Biogeography in the Twentieth Century GUISHED HISTORY, and one inextricably woven into III. Biogeography and the Conservation of the historical development of evolutionary biology and Biodiversity ecology. Modern biogeography now includes an impres- sive diversity of patterns, each of which dealing with some aspect of the spatial variation of nature. Given this, few disciplines can be any more relevant to under- GLOSSARY standing and conserving biological diversity than bioge- ography. biogeography Study of the geographic variation of na- ture, including variation in any biological character- istics (e.g., body size, population density, or species richness) on a geographic scale. continental drift Model first proposed by Alfred Weg- I. INTRODUCTION ener that states that the continents were once united and then were displaced over the surface of the Traditionally, biogeography has been defined as the globe. study of patterns in distributions of geographic ranges plate tectonics Study of the origin, movement, and de- (Brown and Gibson, 1983). During the past three de- struction of the plates and how these processes have cades, however, this field has experienced a great surge been involved in the evolution of Earth’s crust. in development and sophistication, and with this devel- Pleistocene Geologic period from 2 million to 10,000 opment the scope of the field has broadened to include years before the present, which was characterized an impressive diversity of patterns. Simply put, modern by alternating periods of glaciation events and biogeographers now study nearly all aspects of the ‘‘ge- global warming. -

Introduction to Zoogeography Pdf

Introduction to zoogeography pdf Continue zoogeography: The study of the geographical distribution of animals is zoogeography. Vertebrates have characteristic patterns of distribution on land masses. The zoogeography is useful in understanding the evolutionU the increase in the number of animals by reproduction causes them to spread in all directions. The crackdown continues until the barrier is reached. The reason for this intermittent distribution of related groups is the development of barriers or the disappearance of forms in the intermediate area. The idea of zoogeography was originally introduced by P.L Sciater. He studied the geographical distribution of birds in his work Avium Geographicae Distribution Scheme. It divided the continents into six geographical regions. Huxley, grouped into four regions that cover Africa, Eurasia and North America, is called Arktogea. It included South America and Australia under Notogaea. Bluntford divided the land masses into three major divisions of 1,Arctogea; Eurasia; North America and Africa. 2) South American region3) Australian region. According to Darlington, continents around the world can be divided into1. Nearest region2. Palearctic region3. Neotropical region4. Ethiopian region5. Eastern Region6. Australian regions. Adopted system of continental fauna regions.1 . Realm Megagaea : This includes four zoogeographic regions. Region - 1 . Nearctic region : This includes North America and Mexico Abov tropics. Region - 2. Palearctic Region : This region includes Eurasia abo tropics and northern Africa.Region - 3. Eastern Region : This includes tropical Asia and related islands. Ethiopian region : This includes Africa and the southern region of Arabia.II. Neo Realmgaea : Region - 5 . Neotropical region. This includes South America, Central America and southern Mexico.III. -

New Data on the Chewing Lice (Phthiraptera) of Passerine Birds in East of Iran

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/244484149 New data on the chewing lice (Phthiraptera) of passerine birds in East of Iran ARTICLE · JANUARY 2013 CITATIONS READS 2 142 4 AUTHORS: Behnoush Moodi Mansour Aliabadian Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad 3 PUBLICATIONS 2 CITATIONS 110 PUBLICATIONS 393 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Ali Moshaverinia Omid Mirshamsi Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad 10 PUBLICATIONS 17 CITATIONS 54 PUBLICATIONS 152 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Omid Mirshamsi Retrieved on: 05 April 2016 Sci Parasitol 14(2):63-68, June 2013 ISSN 1582-1366 ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE New data on the chewing lice (Phthiraptera) of passerine birds in East of Iran Behnoush Moodi 1, Mansour Aliabadian 1, Ali Moshaverinia 2, Omid Mirshamsi Kakhki 1 1 – Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Faculty of Sciences, Department of Biology, Iran. 2 – Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Pathobiology, Iran. Correspondence: Tel. 00985118803786, Fax 00985118763852, E-mail [email protected] Abstract. Lice (Insecta, Phthiraptera) are permanent ectoparasites of birds and mammals. Despite having a rich avifauna in Iran, limited number of studies have been conducted on lice fauna of wild birds in this region. This study was carried out to identify lice species of passerine birds in East of Iran. A total of 106 passerine birds of 37 species were captured. Their bodies were examined for lice infestation. Fifty two birds (49.05%) of 106 captured birds were infested. Overall 465 lice were collected from infested birds and 11 lice species were identified as follow: Brueelia chayanh on Common Myna (Acridotheres tristis), B. -

Traffic.Org/Home/2015/12/4/ Thousands-Of-Birds-Seized-From-East-Java-Port.Html

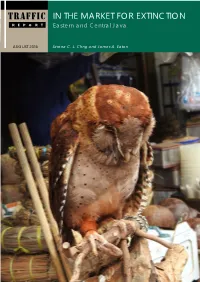

TRAFFIC IN THE MARKET FOR EXTINCTION REPORT Eastern and Central Java AUGUST 2016 Serene C. L. Chng and James A. Eaton TRAFFIC Report: In The Market for Extinction: Eastern and Central Java 1 TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Reprod uction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views of the authors expressed in this publication are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, WWF or IUCN. Published by TRAFFIC. Southeast Asia Regional Office Unit 3-2, 1st Floor, Jalan SS23/11 Taman SEA, 47400 Petaling Jaya Selangor, Malaysia Telephone : (603) 7880 3940 Fax : (603) 7882 0171 Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. © TRAFFIC 2016. ISBN no: 978-983-3393-50-3 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722. Suggested citation: Chng, S.C.L. and Eaton, J.A. (2016). In the Market for Extinction: Eastern and Central Java. TRAFFIC. Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. Front cover photograph: An Oriental Bay Owl Phodilus badius displayed for sale at Malang Bird Market Credit: Heru Cahyono/TRAFFIC IN THE MARKET FOR EXTINCTION Eastern and Central Java Serene C. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Phylogeography of Finches and Sparrows

In: Animal Genetics ISBN: 978-1-60741-844-3 Editor: Leopold J. Rechi © 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 1 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF FINCHES AND SPARROWS Antonio Arnaiz-Villena*, Pablo Gomez-Prieto and Valentin Ruiz-del-Valle Department of Immunology, University Complutense, The Madrid Regional Blood Center, Madrid, Spain. ABSTRACT Fringillidae finches form a subfamily of songbirds (Passeriformes), which are presently distributed around the world. This subfamily includes canaries, goldfinches, greenfinches, rosefinches, and grosbeaks, among others. Molecular phylogenies obtained with mitochondrial DNA sequences show that these groups of finches are put together, but with some polytomies that have apparently evolved or radiated in parallel. The time of appearance on Earth of all studied groups is suggested to start after Middle Miocene Epoch, around 10 million years ago. Greenfinches (genus Carduelis) may have originated at Eurasian desert margins coming from Rhodopechys obsoleta (dessert finch) or an extinct pale plumage ancestor; it later acquired green plumage suitable for the greenfinch ecological niche, i.e.: woods. Multicolored Eurasian goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) has a genetic extant ancestor, the green-feathered Carduelis citrinella (citril finch); this was thought to be a canary on phonotypical bases, but it is now included within goldfinches by our molecular genetics phylograms. Speciation events between citril finch and Eurasian goldfinch are related with the Mediterranean Messinian salinity crisis (5 million years ago). Linurgus olivaceus (oriole finch) is presently thriving in Equatorial Africa and was included in a separate genus (Linurgus) by itself on phenotypical bases. Our phylograms demonstrate that it is and old canary. Proposed genus Acanthis does not exist. Twite and linnet form a separate radiation from redpolls. -

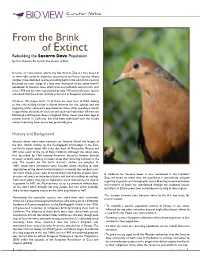

Of Extinct Rebuilding the Socorro Dove Population by Peter Shannon, Rio Grande Zoo Curator of Birds

B BIO VIEW Curator Notes From the Brink of Extinct Rebuilding the Socorro Dove Population by Peter Shannon, Rio Grande Zoo Curator of Birds In terms of conservation efforts, the Rio Grande Zoo is a rare breed in its own right, using its expertise to preserve and breed species whose numbers have dwindled to almost nothing both in the wild and in captivity. Recently, we took charge of a little over one-tenth of the entire world’s population of Socorro doves which have been officially extinct in the wild since 1978 and are now represented by only 100 genetically pure captive individuals that have been carefully preserved in European institutions. Of these 100 unique birds, 13 of them are now here at RGZ, making us the only holding facility in North America for this species and the beginning of this continent’s population for them. After spending a month in quarantine, the birds arrived safe and sound on November 18 from the Edinburgh and Paignton Zoos in England. Other doves have been kept in private aviaries in California, but have been hybridized with the closely related mourning dove, so are not genetically pure. History and Background Socorro doves were once common on Socorro Island, the largest of the four islands making up the Revillagigedo Archipelago in the East- ern Pacific ocean about 430 miles due west of Manzanillo, Mexico and 290 miles south of the tip of Baja, California. Although the doves were first described by 19th century American naturalist Andrew Jackson Grayson, virtually nothing is known about their breeding behavior in the wild. -

A Classification of the Rallidae

A CLASSIFICATION OF THE RALLIDAE STARRY L. OLSON HE family Rallidae, containing over 150 living or recently extinct species T and having one of the widest distributions of any family of terrestrial vertebrates, has, in proportion to its size and interest, received less study than perhaps any other major group of birds. The only two attempts at a classifi- cation of all of the recent rallid genera are those of Sharpe (1894) and Peters (1934). Although each of these lists has some merit, neither is satisfactory in reflecting relationships between the genera and both often separate closely related groups. In the past, no attempt has been made to identify the more primitive members of the Rallidae or to illuminate evolutionary trends in the family. Lists almost invariably begin with the genus Rdus which is actually one of the most specialized genera of the family and does not represent an ancestral or primitive stock. One of the difficulties of rallid taxonomy arises from the relative homo- geneity of the family, rails for the most part being rather generalized birds with few groups having morphological modifications that clearly define them. As a consequence, particularly well-marked genera have been elevated to subfamily rank on the basis of characters that in more diverse families would not be considered as significant. Another weakness of former classifications of the family arose from what Mayr (194933) referred to as the “instability of the morphology of rails.” This “instability of morphology,” while seeming to belie what I have just said about homogeneity, refers only to the characteristics associated with flightlessness-a condition that appears with great regularity in island rails and which has evolved many times. -

An Analysis of Salt Eating in Birds

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1980 An Analysis of Salt Eating in Birds Kathryn Julia Herson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Herson, Kathryn Julia, "An Analysis of Salt Eating in Birds" (1980). Master's Theses. 1909. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1909 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF SALT EATING IN BIRDS by KATHRYN JULIA HERSON A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Biology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1880 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am very graceful for Che advice and help of my thesis committee which conslsced of Dr8, Richard Brewer, Janes Erickson and Michael McCarville, I am parclcularly thankful for my major professor, Dr, Richard Brewer for his extreme diligence and patience In aiding me with Che project. I am also very thankful for all the amateur ornithologists of the Kalamazoo, Michigan, area who allowed me to work on their properties. In this respect I am particularly grateful to Mrs. William McCall of Augusta, Michigan. Last of all I would like to thank all my friends who aided me by lending modes of transportation so that I could pursue the field work. -

Observations on New Or Unusual Birds from Trainidad, West Indies

474 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS SUMMARY CLAUSEN, G., R. SANSON, AND A. STORESUND. 1971. The HbO, dissociation curve of the fulmar and Blood respiratory properties have been compared in the herring gull. Respir. Physiol. 12 :66-70. antarctic birds. Blood hemoglobin content, hemato- DANZER, L. A., AND J. E. COHN. 1967. The dis- crit, and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration sociation curve of goose blood. Respir. Physiol. (MCHC) are higher in three species of penguins 3:302-306. than in the Giant Fulmar and the antarctic Skua. HOLMES, A. D., M. G. PIGGOT, AND P. A. CAhwmLL. Penguin chicks show lower hemoglobin values than 1933. The hemoglobin content of chicken blood. adults. HbO, dissociation curves show higher affin- J. Biol Chem. 103:657. ity in diving than nondiving birds. Among penguins, LENFANT, C., AND K. JOHANSEN. 1965. Gas trans- the Chinstrap Penguin, practicing longer and deeper port by the hemocyanin containing blood of the dives, has blood with higher O? affinity than the other cephalopod, Octopus dofleini. Amer. J. Physiol. species. The Bohr effect is similarly higher in diving 209:991-998. than nondiving birds. The adaptive value of the blood LENFANT, C., G. L. KOOYMAN, R. ELSNER, AND C. M. respiratory properties is discussed in the context of DRABEK. 1969. Respiratory function of blood behavior and mode of life of the species studied. of the adelie penguin, Pygoscelis adeliae. Amer. ACKNOWLEDGMENT J. Physiol. 216: 1598-1600. LUTZ, P. L., I. S. LoNchrmn, J. V. TUTTLE, AND K. This work was supported by the National Science SCHMIDT-NIELSEN. 1973. Dissociation curve of Foundation under grants GV-25401 and GB-24816 bird blood and effect of red cell oxygen consump- to the Scripps Institution of Oceanography for opera- tion. -

Lambusango Forest Conservation Project Research Proposal 2008

Lambusango Forest Research Project OPERATION WALLACEA Research Report 2011 Compiled by Dr Philip Wheeler (email [email protected]) University of Hull Scarborough Campus, Centre for Environmental and Marine Sciences Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Research Sites ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Research activity 2011 ............................................................................................................................ 3 Monitoring bird communities............................................................................................................. 4 Bat community dynamics ................................................................................................................... 9 Monitoring herpetofauna and small mammal communities ........................................................... 11 Butterfly community dynamics ........................................................................................................ 15 Monitoring anoa and wild pig populations ...................................................................................... 19 Habitat associations and sleeping site characteristics