Lord Nuffield Philanthropic Legacy.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tradsheet

The Tradsheet Founded 1967 Are we all ready for another season then? Newsletter of the Traditional Car Club of Doncaster February/March 2019 1 Editorial The clocks go back the weekend I am writing this, the sun has put in an appearance or two already and we have started the season with a breakfast meeting at Ashworth Barracks with a good turnout. Club nights have been very enjoyable all winter with a good num- ber coming along to enjoy each other’s company, some to stay on for the quiz but lighter evenings are on their way and the number of classics in the car park are increasing nicely already. Rodger Tre- hearn has again provided a list of events further on, he has entry forms at all club nights and the information is also on the club web- site, see Chair’s chat for more on that. Planning for the show at the College for the Deaf is well under way and we have fliers for you to give out to get another brilliant attendance. This raises a lot of money for charity and also helps our club fi- nances but, primarily, it is a great day out and is where we do the main club trophy judging. For those who won trophies last year, could you get them back to the club by the end of May please for engraving and getting ready for the show. If anyone needs them collecting, please let me know and I can organise that. We have another club event at Cusworth Hall on 12th May with a car limit of 40 and you must be there by 12 noon and not leave before 4pm to ensure public safety. -

Alan and Richard Jensen Produced Their First Car in 1928 When They

Alan and Richard Jensen produced their first car in 1928 when they converted a five year old Austin 7 Chummy Saloon into a very stylish two seater with cycle guards, louvred bonnet and boat-tail. This was soon sold and replaced with another Austin 7. Then came a car produced on a Standard chassis followed by a series of specials based on the Wolseley Hornet, a popular sporting small car of the time. The early 1930s saw the brothers becoming joint managing directors of commercial coachbuilders W J Smith & Sons and within three years the name of the company was changed to Jensen Motors Limited. Soon bodywork conversions followed on readily available chassis from Morris, Singer, Standard and Wolseley. Jensen’s work did not go unnoticed as they received a commission from actor Clark Gable to produced a car on a US Ford V8 chassis. This stylish car led to an arrangement with Edsel Ford for the production of a range of sports cars using a Jensen designed chassis and powered by Ford V8 engines equipped with three speed Ford transmissions. Next came a series of sporting cars powered by the twin-ignition straight eight Nash engine or the Lincoln V12 unit. On the commercial side of the business Jensen’s were the leaders in the field of the design and construction of high-strength light alloys in commercial vehicles and produced a range of alloy bodied trucks and busses powered by either four-cylinder Ford engines, Ford V8s, or Perkins diesels. World War Two saw sports car production put aside and attentions were turned to more appropriate activities such as producing revolving tank gun turrets, explosives and converting the Sherman Tank for amphibious use in the D-Day invasion of Europe. -

Your Reference

MINI United Kingdom Corporate Communications Media Information 28 March 2013 STRICT EMBARGO 28.03.2013 00:01 GMT MINI PLANT LEADS CELEBRATION OF 100 YEARS OF CAR- MAKING IN OXFORD Transport Secretary opens centenary exhibition in new Visitor Centre and views multi-million pound investment for next generation MINI Today a centenary exhibition was opened in the new Visitor Centre at MINI Plant Oxford by Transport Secretary Patrick McLoughlin and Harald Krueger, Member of the Board of Management of BMW AG, to mark this major industrial milestone. One hundred years ago to the day, the first ‘Bullnose’ Morris Oxford was built by William Morris just a few hundred metres from where the modern MINI plant stands. With a weekly production of just 20 vehicles in 1913, the business grew rapidly and over the century 11.65 million cars were produced, bearing 13 different British brands and one Japanese. Almost 500, 000 people have worked at the plant in the past 100 years and in the early 1960s numbers peaked at 28,000. Today, Plant Oxford employs 3,700 associates who manufacture up to 900 MINIs every day. Congratulating the plant on its historic milestone, Prime Minister David Cameron said: "The Government is working closely with the automotive industry so that it continues to compete and thrive in the global race and the success of MINI around the world stands as a fine example of British BMW Group Company Postal Address manufacturing at its best. The substantial contribution which the Oxford plant BMW (UK) Ltd. Ellesfield Avenue Bracknell Berks RG12 8TA Telephone 01344 480320 Fax 01344 480306 Internet www.bmw.co.uk 0 MINI United Kingdom Corporate Communications Media Information Date 28 March 2013 MINI PLANT LEADS CELEBRATION OF 100 YEARS OF CAR-MAKING IN Subject OXFORD Page 2 has made to the local area and the British economy over the last 100 years is something we should be proud of." Over the years an array of famous cars were produced including the Morris Minor, the Mini, the Morris Marina, the Princess, the Austin Maestro and today’s MINI. -

Safety Fast July 2020

SINCE 1959 NOW IN INDIA VOLUME 1 | JULY 2020 www.mgmotor.co.in WELCOME TO SAFETYFAST! INDIA. WELCOME TO THE WORLD OF MG. Hello and welcome to the first This new chapter also is a leaf of the MG issue of SafetyFast! India. Car Club India just like its UK counterpart. We at MG are excited to extend the It will be an organisation led by passionate world of MG to you via ‘SafetyFast!’, a MG owners for MG owners in India. magazine that has been around for 60 years, Because no matter how good the cars may and has been sought by MG family and get, how much innovation or new features motor enthusiasts the world over. It has we may bring in, what makes MG special excited and captured is you – the owners, every little nudge, poke, drivers, and fans of MG. push and leap MG has I want to reiterate taken towards innovating that we are committed the world of auto-tech. to disruption and The magazine is digital differentiation and the only edition subscription last couple of month for a convenient confirm our beliefs that customer experience. we are on the right path. Available at your Thanks to you all for the fingertips and most support, love for the importantly, contactless brand and great reviews in today’s environment. of our two products We brought this Hector & ZS EV. We are magazine to India as it is devoted to innovation in an iconic part of the MG autotech and hope you as a brand. With the magazine, we plan to will be able to see the same in our bring to you ‘the world of MG’, inform upcoming launch of Gloster. -

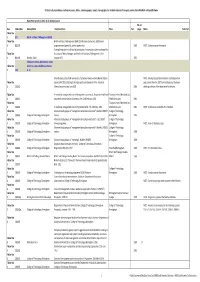

David Bramley Collection - ABS\David Bramley Collection.Xlsx Folder Box Factory Management Course

Collection of presentations, conference papers, letters, company papers, reports, monographs et.al. Includes materials from peers such as Frank Woollard and Lyndall Urwick. David Bramley (19.11.1913 - 31.07.2010) Collection No. of Box Folder/box Author/Editor Title/Description Place Year pages Notes Published Folder Box 1 B2.1 British Institute of Management (BIM) Folder Box British Institute of Management (BIM) 15th National Conference 1960. Dinner 1 B2.1.F1 programme and guests list, section papers et.al. 1960 NOTE: Contains course information. Getting things done in a climate of participation. Presented to a joint meeting of the Folder Box Institution of Works Managers and the British Institute of Management. 23rd 1 B2.1.F1 Bramley, David January 1975. 1975 College prospectus, programme, report, Folder Box brochures, course booklets, invitation 1 C3.1 et. al. Aston Business School 60th anniversary: Testimonial from an alumni Bernard Aston NOTE: Includes copy of Bernard Aston's cerificate and a 4 Folder Box (years 1944-1955) attesting to the high quality and standards of the Industrial page extract from the 1957 Guild of Associates Yearbook 1 C3.1.F1 Administration courses. June 2008. 2008 detailing activities of the department for the year. Folder Box A residential management course. Management course no. 4. Programme leaflet and Training Centre of Birchfield Ltd., 1 C3.1.F1 associated communication documents. 19th -24th February, 1961. Stratford-on-Avon. 1961 Folder Box Training Centre of Birchfield Ltd., 1 C3.1.F1 A residential management course. Programme leaflet. 7th -12th May, 1961. Stratford-on-Avon. 1961 NOTE: certificates presented by F. -

Your Reference

MINI United Kingdom Corporate Communications Media Information 8 March 2013 A CENTURY OF CAR-MAKING IN OXFORD Plant’s first car was a Bullnose Morris Oxford, produced on 28 March 1913 Total car production to date stands at 11,655,000 and counting Over 2,250,000 new MINIs built so far, plus 600,000 classic Minis manufactured at Plant Oxford Scores of models under 14 car brands have been produced at the plant Grew to 28,000 employees in the 1960s As well as cars, produced iron lungs, Tiger Moth aircraft, parachutes, gliders and jerry cans, besides completing 80,000 repairs on Spitfires and Hurricanes Principle part of BMW Group £750m investment for the next generation MINI will be spent on new facilities at Oxford The MINI Plant will lead the celebrations of a centenary of car-making in Oxford, on 28 March 2013 – 100 years to the day when the first “Bullnose” Morris Oxford was built by William Morris, a few hundred metres from where the modern plant stands today. Twenty cars were built each week at the start, but the business grew rapidly and over the century 11.65 million cars were produced. Today, Plant Oxford employs 3,700 associates who manufacture up to 900 MINIs every day, and has contributed over 2.25 million MINIs to the total tally. Major investment is currently under way at the plant to create new facilities for the next generation MINI. BMW Group Company Postal Address BMW (UK) Ltd. Ellesfield Avenue Bracknell Berks RG12 8TA Telephone 01344 480320 Fax 01344 480306 Internet www.bmw.co.uk 0 MINI United Kingdom Corporate Communications Media Information Date Subject A CENTURY OF CAR-MAKING IN OXFORD Page 2 Over the decades that followed the emergence of the Bullnose Morris Oxford in 1913, came cars from a wide range of famous British brands – and one Japanese - including MG, Wolseley, Riley, Austin, Austin Healey, Mini, Vanden Plas, Princess, Triumph, Rover, Sterling and Honda, besides founding marque Morris - and MINI. -

Abingdon Autos LIFE GOALS

UP S AV E TO 20% ON SELECT WINTER PROJECTS! ISSUE 3, 2018 Abingdon Autos The history of a cottage industry LIFE GOALS Going The Distance... MossMotoring.com 20% OFF Overheard in the planning meeting: “How can we announce Motorfest… …so we know it will get noticed?” Mark your calendar and join your sports-car-loving friends the weekend of June 8 for four-wheeled fun for the whole family! Registration coming soon! See The Special Insert Gearbox | Internal Engine & Cylinder Head | Clutch SALE VALID 10/1–11/9/18 4 7 10 14 The Hill Cottage Industry The MGA Effect British Car Myths What does it take to race on a An insider’s look at the history Snakeskin boots are optional. The difference between myth hillclimb? An understanding and community that made up Great memories come and reality may depend on significant other for starters. Abingdon’s auto legacy. standard. your experiences. On the Cover: there is more online! The tip of the iceberg. That’s what you’re holding in your hands. Few people have more fun The MossMotoring.com archive is chock full of stories and a wealth of technical than Julius Abellera. He lives advice. If you could just see the shelves and file cabinets of material each day Triumphully. we’re gradually digitizing… holy smokes! But it is worth it! Check out www.MossMotoring.com today! writers and photographers WE WANT YOU! hare your experience, wisdom and talent with British car enthusiasts across the country. Contributors whose work is selected for use in the magazine will Sreceive Moss Motors Gift Certificates! Now, since there is no way to print all the terrific stories and tech articles that are sent to us, we will place relevant and first-rate submissions on MossMotoring.com for all to enjoy and benefit. -

B R a N D D E

BRAND DECK PREPARED BY LICENSING MANAGEMENT INTERNATIONAL HISTORY British Motor Heritage represents the classic marques of Austin, Morris, Wolseley and Rover together with the iconic British sports cars of MG and Austin-Healey. All are available for worldwide license. The BMH licensed products and designs have been inspired by the original sales brochures and advertising material held in the BMH archive. 1 THE BMH LOGO BRAND ATTRIBUTES ! Elegant ! Refined ! Sophisticated ! Masculine ! A rich British legacy and roots ! Traditional ! Adventurous ! Classic BMC, Nuffield and the Heritage logo are ! Nostalgic/Vintage trademarks of British Motor Heritage. ! Attention to detail ! Style British Motor Heritage and its logos are the registered The British Motor Heritage Brand encompasses a trademarks of British Motor Heritage Limited. The trademarks collection of classic car marques representing the golden were commissioned by the company in 1983 and have been in era of British car manufacturing. continual use ever since. The British Motor Heritage collection of licensed products Over the years, the Heritage trademarks have become the sign utilising the approved marques is targeted at men over 21 for quality of service and manufacture. The use of the logos has who may have fond sentimental memories of owning their been identified with Specialist Approval which is the Quality own MGs, Morris Minors or Austin-Healeys in their youth. Benchmark for the Classic Car Industry and with Quality Original Equipment product. We believe that collectors of fine wine, memorabilia and classic cars would be a key target for this Brand. The BMH Brand offers a prime opportunity for gift giving. 2 BMH MARQUES THE BMH MARQUES ARE AS FOLLOWS 3 BMH MARQUES - AUSTIN Registered in 1909, the Austin Word form was used on cars and literature well into the late 1930s. -

Morris Garages Ltd, Then Morris Motors

Official name: Morris Garages Ltd, then Morris Motors, then The Nuffield Organisation, then British Motor Corporation, then British Motor Holdings, Leyland Motor Corporation, British Leyland Motor Corporation, British Leyland Limited, Austin Rover Group, then Rover Group, then MG Rover. The company went bankrupt in 2005. Owned by: Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation. Current situation: MGs are now built in China, with a few assembled at the old MG factory in England. However, many car designs are very old and all are poorly built. MG has not been a a big hit in China and sales outside China have been dreadful. Chances of survival: poor. SAIC is staying alive thanks to Chinese government handouts and joint ventures with Western companies. If MG’s new owners are relying on Western sales to prosper, they are probably in for a lonely old age • 1 All content © The Dog & Lemon Guide 2016 • All rights reserved A brief history of MG (and why things went so badly wrong) WAS ORIGINALLY an abbreviation MGof Morris Garages. Founded in 1924 by William Morris, MG sportscars were based on the basic structure of Morris’s other cars from that era. MGs soon developed a reputation for being fast and nimble. Sales boomed. Originally owned personally by William Morris, MG was sold in 1935 to the Morris parent company. This put MG on a sound financial footing, but also made MG a tiny subsiduary of a major corporation. Uncredited images are believed to be in the public domain. Credited images are copyright their respective 2 All content © The Dog & Lemon Guide 2016 • All rights reserved owners. -

The MG Car Club Geelong Inc

The MG Car Club Geelong Inc. Selected Indexes of articles in indexed magazines. Many of these magazines are missing from our Library, please return if you have them. The Index is not complete but is a 'work in progress' and will be updated regularly. Only articles of on-going historical or technical interest are indexed. I have included any articles about the history of the MG Company, MG cars, or the people who were involved in either. I have not listed articles about Club Runs, Competition Events, or non-technical reports of Club Members' MGs as many of these are only relevant to Members in the UK. Use <Ctrl><f> to open the pdf search box to find keywords from articles, or to jump to the latest indexed edition of the magazines. To go to latest:- BMC Experience, insert text "latestbmc" in the search box MGCC G-Torque, insert text "latestgtorque" in the search box Octane, insert text "latestoctane" in the search box MG Octagon CC Bulletin, insert text 'latestoctagonbulletin' in the search box Librarian - The MGCC Geelong Inc. Index of Technical Articles from G-Torque - MGCC Geelong Magazine Edition Article Title EDITION ARTICLE PAGES 1990 Believe it or Not - This article is a personal account of installing an Austin 1800 engine in an MGB. It has good February 1990 basic information and tips on how to install the engine and some pitfalls.Barry Arthur Bits and Pieces - A brief description outlining the factors of MG handling and what may fix it. For example front March 1990 sway bar, ride height tyre pressure. -

9518 the LONDON GAZETTE, Loxn NOVEMBER 1964

9518 THE LONDON GAZETTE, lOxn NOVEMBER 1964 Bristol Co-operative Society Ltd. Confectionery Lister and Co. Ltd. South Mill, Manningham Mills, Department, Chester Road, Whitehall, Bristol 5. Bradford 9. British Insulated Callender's Cables Ltd. Prescot. Lithomasters (R. E. Wilson and J. A. W. Harrison The British Oxygen Co. Ltd. Quasi Arc Works, t/a). Harris Street, Camberwell, London S.E.5. Oxford Street, Bilston. London Transport Board. Cockfosters Depot, Bramley British Sealed Beams Ltd. Rockingham Road,^Corby. Road, Southgate, London N.I4, Ealing Common British Sugar Corporation Ltd. Foley Park, Kidder- Depot, Granville Gardens, Ealing, London W.5, minster, Ipswich Road, Sproughton, Ipswich, Queen Hainault Depot, New North Road, Hainault, Adelaide, Ely and Sugar Factory, Brigg. Morden Depot, Epsom Road, Morden, Neasden B S R Ltd. College Milton, East Kilbride. Depot, North Circular Road, Neasden, London Busby Spinning Co. Ltd. Bridgend Mills, Kilwinning. N.W.10, Ruislip Depot, West End Road, Ruislip, Cairnryan Ltd. Lochryanside, Stranraer. and Upminster Depot, Front Lane, Cranham, J. and J. Cash Ltd. Kingfield Works, Kingfield Road, Upminster. Coventry. John Lumb and Co. (Division of United Glass Ltd.). Chapman & Co. (Balham) Ltd. Canterbury Mills, Cheeseborough Yard, Albion Street, Castleford, and Canterbury Road, Croydon. Hightown Works, Albion Street, Castleford. George Christie Ltd. Broomloan Road, Glasgow Mansfields (Norwich) Ltd. Peacock Street, Norwich, S.W.I. and St. Saviours Lane, Norwich. Cleveland Twist Drill (Great Britain) Ltd. Station Marshall, Kaye & Marshall Ltd. Oaklands Mill, Road, Peterhead. Netherfield Road, Ravensthorpe, Dewsbury. Clyde Paper Co. Ltd. Cambuslang Road, Rutherglen, Marshall •& Snelgrove (Marshalls Ltd. T/A). Bond Glasgow. Street, Leeds 1. -

Austin Motor Company

Austin Motor Company Few names in British motoring history are better known than that of Austin. For many years the company claimed that ‘You buy a car but you invest in an Austin’. A young Herbert Austin (1866–1941) travelled to Australia in 1884 seeking his fortune. In mid 1886 he began working for Frederick Wolseley’s Sheep Shearing Machine Company in Sydney. Austin returned to England with Wolseley in 1889 to establish a new factory in Birmingham, where he became Works Manager. Austin built himself a car in 1895/6 followed a few months later by a second for Wolseley, a production model followed in 1899. A new company, backed by Vickers, bought the car making interests of the Wolseley Company in 1901 with Austin taking a leading role. Following a disagreement over engine design in 1905 Austin left, setting up his own Austin Motor Company in a disused printing works at Longbridge in December of that year. The first Austin was a 4 cylinder 5182cc 25/30hp model which became available in the spring of 1906. This was replaced by the 4396cc 18/24 in 1907. 5838cc 40hp and 6 cylinder 8757cc 60hp models were also produced. The 6 cylinder engine also formed the basis for a 9657cc 100hp engine used in cars for the 1908 Grand Prix. A 7hp single cylinder car was marketed in 1910/11. The company expanded rapidly, output growing from 200 cars in 1910 to 1100 in 1912. By 1914 there was a three model line-up of Ten, Twenty and Thirty. The Austin Company underwent a massive expansion during World War I with the workforce growing from 2,600 to more than 22,000.