Proprietors and Managers: Structure and Technique in Large British Enterprise 1890 to 1939

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDUCATION of POOR GIRLS in NORTH WEST ENGLAND C1780 to 1860: a STUDY of WARRINGTON and CHESTER by Joyce Valerie Ireland

EDUCATION OF POOR GIRLS IN NORTH WEST ENGLAND c1780 to 1860: A STUDY OF WARRINGTON AND CHESTER by Joyce Valerie Ireland A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire September 2005 EDUCATION OF POOR GIRLS IN NORTH WEST ENGLAND cll8Oto 1860 A STUDY OF WARRINGTON AND CHESTER ABSTRACT This study is an attempt to discover what provision there was in North West England in the early nineteenth century for the education of poor girls, using a comparative study of two towns, Warrington and Chester. The existing literature reviewed is quite extensive on the education of the poor generally but there is little that refers specifically to girls. Some of it was useful as background and provided a national framework. In order to describe the context for the study a brief account of early provision for the poor is included. A number of the schools existing in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries continued into the nineteenth and occasionally even into the twentieth centuries and their records became the source material for this study. The eighteenth century and the early nineteenth century were marked by fluctuating fortunes in education, and there was a flurry of activity to revive the schools in both towns in the early nineteenth century. The local archives in the Chester/Cheshire Record Office contain minute books, account books and visitors' books for the Chester Blue Girls' school, Sunday and Working schools, the latter consolidated into one girls' school in 1816, all covering much of the nineteenth century. -

Classic Vehicle Auctionauctionauction

Classic Vehicle AuctionAuctionAuction Friday 28th April 2017 Commencing at 11AM Being held at: South Western Vehicle Auctions Limited 61 Ringwood Road, Parkstone, Poole, Dorset, BH14 0RG Tel:+44(0)1202745466 swva.co.ukswva.co.ukswva.co.uk £5 CLASSIC VEHICLE AUCTIONS EXTRA TERMS & CONDITIONS NB:OUR GENERAL CONDITIONS OF SALE APPLY THE ESTIMATES DO NOT INCLUDE BUYERS PREMIUM COMMISSION – 6% + VAT (Minimum £150 inc VAT) BUYERS PREMIUM – 8% + VAT (Minimum £150 inc VAT) ONLINE AND TELEPHONE BIDS £10.00 + BUYERS PREMIUM + VAT ON PURCHASE 10% DEPOSIT, MINIMUM £500, PAYABLE ON THE FALL OF THE HAMMER AT THE CASH DESK. DEPOSITS CAN BE PAID BY DEBIT CARD OR CASH (Which is subject to 1.25% Surcharge) BALANCES BY NOON ON THE FOLLOWING MONDAY. BALANCES CAN BE PAID BY DEBIT CARD, BANK TRANSFER, CASH (Which is subject to 1.25% surcharge), OR CREDIT CARD (Which is subject to 3.5% surcharge) ALL VEHICLES ARE SOLD AS SEEN PROSPECTIVE PURCHASERS ARE ADVISED TO SATISFY THEMSELVES AS TO THE ACCURACY OF ANY STATEMENT MADE, BE THEY STATEMENTS OF FACT OR OPINION. ALL MILEAGES ARE SOLD AS INCORRECT UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED CURRENT ENGINE AND CHASSIS NUMBERS ARE SUPPLIED BY HPI. ALL VEHICLES MUST BE COLLECTED WITHIN 3 WEEKS, AFTER 3 WEEKS STORAGE FEES WILL INCUR Lot 1 BENTLEY - 4257cc ~ 1949 LLG195 is the second Bentley (see lot 61) that the late Mr Wells started to make into a special in the 1990's. All the hard work has been done ie moving the engine back 18 inches, shortening the propshaft and making a new bulkhead, the aluminium special body is all there bar a few little bits which need finishing. -

A562 Penketh Rd River Me Ey Manchester Ship Canal W Est

KEY A562 Penketh Rd Site boundary Railway Road network Public Rights of Way Transpennine Trail West Water courses Existing water bodies Moore Nature Reserve Area Existing green spaces A5060 Existing woodland and trees Disussed Runcorn & Latchford canal walk Ecologically significant reed beds y e Existing access point to the site rs e Existing access point to the landfill site River M e n li n A56 Coast Mai est W al Can M Ship o ster or che e Man L ane Ecology Plan Warrington Waterfront: Port Warrington, Warrington Commercial Park and Moore Nature Reserve and Country Park 25 Conservation Area 1. Walton Village 2. Moore Locally Listed 1. Upper Moss Side Farm, Moss SideLane,Cuerdley 2. Lower Moss Side Farm, Lapwing Lane, Cuerdley 3. Sankey Bridge, Old Liverpool Road, Great Sankey 4. Ferry Inn Public House, Fiddlers Ferry, Penketh 5. The Sloop Public House, Old Liverpool Road, Warrington 6. The Coach and Horses Public House, Old Liverpool Road,Warrington. 7. Bethany Pentecostal Church, Old Liverpool Road, Warrington. Listed Building 1. Monks Siding Signal Box 2. Moore Lane Bridge 3. The Black Horse Public House 4. Transporter Bridge to Part of Joseph Crosfield and Sons Ltd’s Works. 5. Moore Lane Bridge (Over Manchester Ship Canal). 6. Church of St Luke. Heritage Plan 26 Warrington Waterfront: Port Warrington, Warrington Commercial Park and Moore Nature Reserve and Country Park Image showing the listed Moore Lane Bridge on the southern boundary of the Site Warrington Waterfront: Port Warrington, Warrington Commercial Park and Moore Nature Reserve and Country Park 27 A562 Penketh Rd Transpennine Trail West Site Constraints and Opportunities 4.28 The baseline evidence has identified the overall constraints and opportunities of the Site, as illustrated in the following plans. -

Report on the Affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, Mg Rover Group Limited and 33 Other Companies Volume I

REPORT ON THE AFFAIRS OF PHOENIX VENTURE HOLDINGS LIMITED, MG ROVER GROUP LIMITED AND 33 OTHER COMPANIES VOLUME I Gervase MacGregor FCA Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Report on the affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, MG Rover Group Limited and 33 other companies by Gervase MacGregor FCA and Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Volume I Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail TSO PO Box 29, Norwich, NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone 0870 240 3701 TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Customers can also order publications from: TSO Ireland 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD Tel 028 9023 8451 Fax 028 9023 5401 Published with the permission of the Department for Business Innovation and Skills on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright 2009 All rights reserved. Copyright in the typographical arrangement and design is vested in the Crown. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. First published 2009 ISBN 9780 115155239 Printed in the United Kingdom by the Stationery Office N6187351 C3 07/09 Contents Chapter Page VOLUME -

Wealthy Business Families in Glasgow and Liverpool, 1870-1930 a DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY In Trade: Wealthy Business Families in Glasgow and Liverpool, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Emma Goldsmith EVANSTON, ILLINOIS December 2017 2 Abstract This dissertation provides an account of the richest people in Glasgow and Liverpool at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. It focuses on those in shipping, trade, and shipbuilding, who had global interests and amassed large fortunes. It examines the transition away from family business as managers took over, family successions altered, office spaces changed, and new business trips took hold. At the same time, the family itself underwent a shift away from endogamy as young people, particularly women, rebelled against the old way of arranging marriages. This dissertation addresses questions about gentrification, suburbanization, and the decline of civic leadership. It challenges the notion that businessmen aspired to become aristocrats. It follows family businessmen through the First World War, which upset their notions of efficiency, businesslike behaviour, and free trade, to the painful interwar years. This group, once proud leaders of Liverpool and Glasgow, assimilated into the national upper-middle class. This dissertation is rooted in the family papers left behind by these families, and follows their experiences of these turbulent and eventful years. 3 Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without the advising of Deborah Cohen. Her inexhaustible willingness to comment on my writing and improve my ideas has shaped every part of this dissertation, and I owe her many thanks. -

The Automobile in Japan

International and Japanese Studies Symposium The Automobile in Japan Stewart Lone, Associate Professor of East Asian History, Australian Defence Force Academy, Canberra Japan and the Age of Speed: Urban Society and the Automobile, 1925-30 p.1 Christopher Madeley, Chaucer College, Canterbury Kaishinsha, DAT, Nissan and the British Motor Vehicle Industry p.15 The Suntory Centre Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines London School of Economics and Political Science Discussion Paper Houghton Street No. IS/05/494 London WC2A 2AE July 2005 Tel: 020-7955-6699 Preface A symposium was held in the Michio Morishima room at STICERD on 7 April 2005 to discuss aspects of the motor industry in Japan. Stewart Lone discussed the impact which the introduction of the motor car had on Japan’s urban society in the 1920s, especially in the neighbourhood of the city of Kyoto. By way of contrast, Christopher Madeley traced the relationship between Nissan (and its predecessors) and the British motor industry, starting with the construction of the first cars in 1912 by the Kaishinsha Company, using chassis imported from Swift of Coventry. July 2005 Abstracts Lone: The 1920s saw the emergence in Kansai of modern industrial urban living with the development of the underground, air services; wireless telephones, super express trains etc. Automobiles dominated major streets from the early 1920s in the new Age of Speed. Using Kyoto city as an example, the article covers automobile advertising, procedures for taxis, buses and cars and traffic safety and regulation. Madeley: Nissan Motor Company had a longer connection with the British industry than any other Japanese vehicle manufacturer. -

The Tradsheet

The Tradsheet Founded 1967 Are we all ready for another season then? Newsletter of the Traditional Car Club of Doncaster February/March 2019 1 Editorial The clocks go back the weekend I am writing this, the sun has put in an appearance or two already and we have started the season with a breakfast meeting at Ashworth Barracks with a good turnout. Club nights have been very enjoyable all winter with a good num- ber coming along to enjoy each other’s company, some to stay on for the quiz but lighter evenings are on their way and the number of classics in the car park are increasing nicely already. Rodger Tre- hearn has again provided a list of events further on, he has entry forms at all club nights and the information is also on the club web- site, see Chair’s chat for more on that. Planning for the show at the College for the Deaf is well under way and we have fliers for you to give out to get another brilliant attendance. This raises a lot of money for charity and also helps our club fi- nances but, primarily, it is a great day out and is where we do the main club trophy judging. For those who won trophies last year, could you get them back to the club by the end of May please for engraving and getting ready for the show. If anyone needs them collecting, please let me know and I can organise that. We have another club event at Cusworth Hall on 12th May with a car limit of 40 and you must be there by 12 noon and not leave before 4pm to ensure public safety. -

Alan and Richard Jensen Produced Their First Car in 1928 When They

Alan and Richard Jensen produced their first car in 1928 when they converted a five year old Austin 7 Chummy Saloon into a very stylish two seater with cycle guards, louvred bonnet and boat-tail. This was soon sold and replaced with another Austin 7. Then came a car produced on a Standard chassis followed by a series of specials based on the Wolseley Hornet, a popular sporting small car of the time. The early 1930s saw the brothers becoming joint managing directors of commercial coachbuilders W J Smith & Sons and within three years the name of the company was changed to Jensen Motors Limited. Soon bodywork conversions followed on readily available chassis from Morris, Singer, Standard and Wolseley. Jensen’s work did not go unnoticed as they received a commission from actor Clark Gable to produced a car on a US Ford V8 chassis. This stylish car led to an arrangement with Edsel Ford for the production of a range of sports cars using a Jensen designed chassis and powered by Ford V8 engines equipped with three speed Ford transmissions. Next came a series of sporting cars powered by the twin-ignition straight eight Nash engine or the Lincoln V12 unit. On the commercial side of the business Jensen’s were the leaders in the field of the design and construction of high-strength light alloys in commercial vehicles and produced a range of alloy bodied trucks and busses powered by either four-cylinder Ford engines, Ford V8s, or Perkins diesels. World War Two saw sports car production put aside and attentions were turned to more appropriate activities such as producing revolving tank gun turrets, explosives and converting the Sherman Tank for amphibious use in the D-Day invasion of Europe. -

The Magazine of the Triumph Car Club of Victoria Inc. TRIUMPH SPARES P\L (Incorporating the Previous General and Sporting Automotive)

THE TRIUMPH TRUMPET TTT H CA P R C M L IU U R T B November Triumph 2005 O F IA VICTOR The Magazine of the Triumph Car Club of Victoria Inc. TRIUMPH SPARES P\L (Incorporating the previous General and Sporting Automotive) Triumph Full Range of New and Used Parts for all Models Mechanical Repairs 77 - 79 Station Street Fairfield 3078 Phone: (03) 9486 3711 Facsimile (03) 9486 3535 Present Your Membership Card To Receive A Discount November 2005 The Triumph Trumpet 1 The Triumph Car Club of Victoria is a participating member of the Association of TRUMPET Motoring Clubs Delegates: Syd Journal of the Triumph Car Club of Victoria, Inc Gallagher and Paul Wallace. The Triumph Car Club is Table of Contents an Authorised Club under the VicRoads’ Club Permit Chris's Procrastinations 3 Scheme. Club Permit From the President’s Desk 5 Secretary, Syd Gallagher, Minutes of Sept General Meeting 6 phone – 9772 6537. Celebrity Driver 7 Coming Events 8 Articles in the Triumph You Know your Driving an Old Car, When.... 10 Trumpet may be quoted Stafford’s Ramblings 11 without permission, however, Clubman Points Explained 12 due acknowledgment must be Photo Competition 12 made. Triumph of Spirit 14 Ensay Report 16 This magazine is published Pictures from Ensay 17 every month, except Sir Alex Issigonis 18 December, and is mailed on the Tuesday preceding Marque Time 21 the Club’s monthly General If You Ever Felt Stupid 25 Meetings. Collation is the evening before mailing day, and articles should reach the Editor by the Deadline date Index of Club Services referred to in the Editorial. -

Your Reference

MINI United Kingdom Corporate Communications Media Information 28 March 2013 STRICT EMBARGO 28.03.2013 00:01 GMT MINI PLANT LEADS CELEBRATION OF 100 YEARS OF CAR- MAKING IN OXFORD Transport Secretary opens centenary exhibition in new Visitor Centre and views multi-million pound investment for next generation MINI Today a centenary exhibition was opened in the new Visitor Centre at MINI Plant Oxford by Transport Secretary Patrick McLoughlin and Harald Krueger, Member of the Board of Management of BMW AG, to mark this major industrial milestone. One hundred years ago to the day, the first ‘Bullnose’ Morris Oxford was built by William Morris just a few hundred metres from where the modern MINI plant stands. With a weekly production of just 20 vehicles in 1913, the business grew rapidly and over the century 11.65 million cars were produced, bearing 13 different British brands and one Japanese. Almost 500, 000 people have worked at the plant in the past 100 years and in the early 1960s numbers peaked at 28,000. Today, Plant Oxford employs 3,700 associates who manufacture up to 900 MINIs every day. Congratulating the plant on its historic milestone, Prime Minister David Cameron said: "The Government is working closely with the automotive industry so that it continues to compete and thrive in the global race and the success of MINI around the world stands as a fine example of British BMW Group Company Postal Address manufacturing at its best. The substantial contribution which the Oxford plant BMW (UK) Ltd. Ellesfield Avenue Bracknell Berks RG12 8TA Telephone 01344 480320 Fax 01344 480306 Internet www.bmw.co.uk 0 MINI United Kingdom Corporate Communications Media Information Date 28 March 2013 MINI PLANT LEADS CELEBRATION OF 100 YEARS OF CAR-MAKING IN Subject OXFORD Page 2 has made to the local area and the British economy over the last 100 years is something we should be proud of." Over the years an array of famous cars were produced including the Morris Minor, the Mini, the Morris Marina, the Princess, the Austin Maestro and today’s MINI. -

Safety Fast July 2020

SINCE 1959 NOW IN INDIA VOLUME 1 | JULY 2020 www.mgmotor.co.in WELCOME TO SAFETYFAST! INDIA. WELCOME TO THE WORLD OF MG. Hello and welcome to the first This new chapter also is a leaf of the MG issue of SafetyFast! India. Car Club India just like its UK counterpart. We at MG are excited to extend the It will be an organisation led by passionate world of MG to you via ‘SafetyFast!’, a MG owners for MG owners in India. magazine that has been around for 60 years, Because no matter how good the cars may and has been sought by MG family and get, how much innovation or new features motor enthusiasts the world over. It has we may bring in, what makes MG special excited and captured is you – the owners, every little nudge, poke, drivers, and fans of MG. push and leap MG has I want to reiterate taken towards innovating that we are committed the world of auto-tech. to disruption and The magazine is digital differentiation and the only edition subscription last couple of month for a convenient confirm our beliefs that customer experience. we are on the right path. Available at your Thanks to you all for the fingertips and most support, love for the importantly, contactless brand and great reviews in today’s environment. of our two products We brought this Hector & ZS EV. We are magazine to India as it is devoted to innovation in an iconic part of the MG autotech and hope you as a brand. With the magazine, we plan to will be able to see the same in our bring to you ‘the world of MG’, inform upcoming launch of Gloster. -

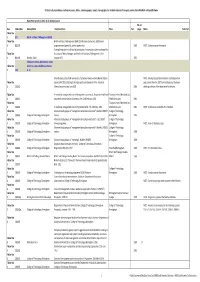

David Bramley Collection - ABS\David Bramley Collection.Xlsx Folder Box Factory Management Course

Collection of presentations, conference papers, letters, company papers, reports, monographs et.al. Includes materials from peers such as Frank Woollard and Lyndall Urwick. David Bramley (19.11.1913 - 31.07.2010) Collection No. of Box Folder/box Author/Editor Title/Description Place Year pages Notes Published Folder Box 1 B2.1 British Institute of Management (BIM) Folder Box British Institute of Management (BIM) 15th National Conference 1960. Dinner 1 B2.1.F1 programme and guests list, section papers et.al. 1960 NOTE: Contains course information. Getting things done in a climate of participation. Presented to a joint meeting of the Folder Box Institution of Works Managers and the British Institute of Management. 23rd 1 B2.1.F1 Bramley, David January 1975. 1975 College prospectus, programme, report, Folder Box brochures, course booklets, invitation 1 C3.1 et. al. Aston Business School 60th anniversary: Testimonial from an alumni Bernard Aston NOTE: Includes copy of Bernard Aston's cerificate and a 4 Folder Box (years 1944-1955) attesting to the high quality and standards of the Industrial page extract from the 1957 Guild of Associates Yearbook 1 C3.1.F1 Administration courses. June 2008. 2008 detailing activities of the department for the year. Folder Box A residential management course. Management course no. 4. Programme leaflet and Training Centre of Birchfield Ltd., 1 C3.1.F1 associated communication documents. 19th -24th February, 1961. Stratford-on-Avon. 1961 Folder Box Training Centre of Birchfield Ltd., 1 C3.1.F1 A residential management course. Programme leaflet. 7th -12th May, 1961. Stratford-on-Avon. 1961 NOTE: certificates presented by F.