Storylines Southeast Native American Cultures Value Tradition and Strive to Keep the Discussion Guide No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ellen Glasgow's in This Our Life

69 Ellen Glasgow’s In This Our Life DOI: 10.2478/abcsj-2019-0016 American, British and Canadian Studies, Volume 33, December 2019 Ellen Glasgow’s In This Our Life: “The Betrayals of Life” in the Crumbling Aristocratic South IULIA ANDREEA MILICĂ Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iași, Romania Abstract Ellen Glasgow’s works have received, over time, a mixed interpretation, from sentimental and conventional, to rebellious and insightful. Her novel In This Our Life (1941) allows the reader to have a glimpse of the early twentieth-century South, changed by the industrial revolution, desperately clinging to dead codes, despairing and struggling to survive. The South is reflected through the problems of a family, its sentimentality and vulnerability, but also its cruelty, pretensions, masks and selfishness, trying to find happiness and meaning in a world of traditions and codes that seem powerless in the face of progress. The novel, apparently simple and reduced in scope, offers, in fact, a deep insight into various issues, from complicated family relationships, gender pressures, racial inequality to psychological dilemmas, frustration or utter despair. The article’s aim is to depict, through this novel, one facet of the American South, the “aristocratic” South of belles and cavaliers, an illusory representation indeed, but so deeply rooted in the world’s imagination. Ellen Glasgow is one of the best choices in this direction: an aristocratic woman but also a keen and profound writer, and, most of all, a writer who loved the South deeply, even if she exposed its flaws. Keywords : the South, aristocracy, cavalier, patriarchy, southern belle, women, race, illness The American South is an entity recognizable in the world imagination due to its various representations in fiction, movies, politics, entertainment, advertisements, etc.: white-columned houses, fields of cotton, belles and cavaliers served by benevolent slaves, or, on the contrary, poverty, violence and lynching. -

Hypnotherapy.Pdf

Hypnotherapy An Exploratory Casebook by Milton H. Erickson and Ernest L. Rossi With a Foreword by Sidney Rosen IRVINGTON PUBLISHERS, Inc., New York Halsted Press Division of JOHN WILEY Sons, Inc. New York London Toronto Sydney The following copyrighted material is reprinted by permission: Erickson, M. H. Concerning the nature and character of post-hypnotic behavior. Journal of General Psychology, 1941, 24, 95-133 (with E. M. Erickson). Copyright © 1941. Erickson, M. H. Hypnotic psychotherapy. Medical Clinics of North America, New York Number, 1948, 571-584. Copyright © 1948. Erickson, M. H. Naturalistic techniques of hypnosis. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 1958, 1, 3-8. Copyright © 1958. Erickson, M. H. Further clinical techniques of hypnosis: utilization techniques. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 1959, 2, 3-21. Copyright © 1959. Erickson, M. H. An introduction to the study and application of hypnosis for pain control. In J. Lassner (Ed.), Hypnosis and Psychosomatic Medicine: Proceedings of the International Congress for Hypnosis and Psychosomatic Medicine. Springer Verlag, 1967. Reprinted in English and French in the Journal of the College of General Practice of Canada, 1967, and in French in Cahiers d' Anesthesiologie, 1966, 14, 189-202. Copyright © 1966, 1967. Copyright © 1979 by Ernest L. Rossi, PhD All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatever, including information storage or retrieval, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews), without written permission from the publisher. For information, write to Irvington Publishers, Inc., 551 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10017. Distributed by HALSTED PRESS A division of JOHN WILEY SONS, Inc., New York Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Erickson, Milton H. -

Fruitful Futility: Land, Body, and Fate in Ellen Glasgow's Barren Ground Katelin R

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in English Department of English 12-2014 Fruitful Futility: Land, Body, and Fate in Ellen Glasgow's Barren Ground Katelin R. Moquin St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Moquin, Katelin R., "Fruitful Futility: Land, Body, and Fate in Ellen Glasgow's Barren Ground" (2014). Culminating Projects in English. 2. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in English by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moquin 1 FRUITFUL FUTILITY: LAND, BODY, AND FATE IN ELLEN GLASGOW’S BARREN GROUND by Katelin Ruth Moquin B.A., Concordia University – Ann Arbor, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree: Master of Arts St. Cloud, Minnesota December, 2014 Moquin 2 FRUITFUL FUTILITY: LAND, BODY, AND FATE IN ELLEN GLASGOW’S BARREN GROUND Katelin Ruth Moquin Through a Cultural Studies lens and with Formalist-inspired analysis, this thesis paper addresses the complexly interwoven elements of land, body, and fate in Ellen Glasgow’s Barren Ground . The introductory chapter is a survey of the critical attention, and lack thereof, Glasgow has received from various literary frameworks. Chapter II summarizes the historical foundations of the South into which Glasgow’s fictionalized South is rooted. -

Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories Jill Sneider Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 5-24-2012 Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories Jill Sneider Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Sneider, Jill, "Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories" (2012). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 728. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/728 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of English Dissertation Examination Committee: Wayne Fields, Chair Naomi Lebowitz Robert Milder George Pepe Richard Ruland Lynne Tatlock Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories By Jill Frank Sneider A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2012 St. Louis, Missouri Copyright by Jill Frank Sneider 2012 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Washington University and the Department of English and American Literature for their flexibility during my graduate education. Their approval of my part-time program made it possible for me to earn a master’s degree and a doctorate. I appreciate the time, advice, and encouragement given to me by Wayne Fields, the Director of my dissertation. He helped me discover new facets to explore every time we met and challenged me to analyze and write far beyond my own expectations. -

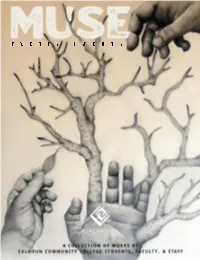

Muse-2020-SINGLES1-1.Pdf

TWENTY TWENTY Self Portrait Heidi Hughes contents Poetry clarity Jillian Oliver ................................................................... 2 I Know You Rayleigh Caldwell .................................................. 2 strawberry Bailey Stuart ........................................................... 3 The Girl Behind the Mirror Erin Gonzalez .............................. 4 exile from neverland Jillian Oliver ........................................... 7 I Once… Erin Gonzalez .............................................................. 7 if ever there should come a time Jillian Oliver ........................ 8 Hello Friend Julia Shelton The Trend Fernanda Carbajal Rodriguez .................................. 9 Love Sonnet Number 666 ½ Jake C. Woodlee .........................11 the end of romance Jillian Oliver ............................................11 What Kindergarten Taught Me Morgan Bryson ..................... 43 Facing Fear Melissa Brown ....................................................... 44 Sharing the Love with Calhoun’s Community ........................... 44 ESSAY Dr. Leigh Ann Rhea J.K. Rowling: The Modern Hero Melissa Brown ................... 12 In the Spotlight: Tatayana Rice Jillian Oliver ......................... 45 Corn Flakes Lance Voorhees .................................................... 15 Student Success Symposium Jillian Oliver .............................. 46 Heroism in The Outcasts of Poker Flat Molly Snoddy .......... 15 In the Spotlight: Chad Kelsoe Amelia Chey Slaton ............... -

Following the Equator by Mark Twain</H1>

Following the Equator by Mark Twain Following the Equator by Mark Twain This etext was produced by David Widger FOLLOWING THE EQUATOR A JOURNEY AROUND THE WORLD BY MARK TWAIN SAMUEL L. CLEMENS HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT THE AMERICAN PUBLISHING COMPANY MDCCCXCVIII COPYRIGHT 1897 BY OLIVIA L. CLEMENS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FORTIETH THOUSAND THIS BOOK page 1 / 720 Is affectionately inscribed to MY YOUNG FRIEND HARRY ROGERS WITH RECOGNITION OF WHAT HE IS, AND APPREHENSION OF WHAT HE MAY BECOME UNLESS HE FORM HIMSELF A LITTLE MORE CLOSELY UPON THE MODEL OF THE AUTHOR. THE PUDD'NHEAD MAXIMS. THESE WISDOMS ARE FOR THE LURING OF YOUTH TOWARD HIGH MORAL ALTITUDES. THE AUTHOR DID NOT GATHER THEM FROM PRACTICE, BUT FROM OBSERVATION. TO BE GOOD IS NOBLE; BUT TO SHOW OTHERS HOW TO BE GOOD IS NOBLER AND NO TROUBLE. CONTENTS CHAPTER I. The Party--Across America to Vancouver--On Board the Warrimo--Steamer Chairs-The Captain-Going Home under a Cloud--A Gritty Purser--The Brightest Passenger--Remedy for Bad Habits--The Doctor and the Lumbago --A Moral Pauper--Limited Smoking--Remittance-men. page 2 / 720 CHAPTER II. Change of Costume--Fish, Snake, and Boomerang Stories--Tests of Memory --A Brahmin Expert--General Grant's Memory--A Delicately Improper Tale CHAPTER III. Honolulu--Reminiscences of the Sandwich Islands--King Liholiho and His Royal Equipment--The Tabu--The Population of the Island--A Kanaka Diver --Cholera at Honolulu--Honolulu; Past and Present--The Leper Colony CHAPTER IV. Leaving Honolulu--Flying-fish--Approaching the Equator--Why the Ship Went Slow--The Front Yard of the Ship--Crossing the Equator--Horse Billiards or Shovel Board--The Waterbury Watch--Washing Decks--Ship Painters--The Great Meridian--The Loss of a Day--A Babe without a Birthday CHAPTER V. -

THE JUNGLE by VICTORIA ALLEN, M.Ed

A TEACHER’S GUIDE TO THE SIGNET CLASSIC EDITION OF UPTON SINCLAIR’S THE JUNGLE By VICTORIA ALLEN, M.Ed. SERIES EDITORS: W. GEIGER ELLIS, ED.D., UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, EMERITUS and ARTHEA J. S. REED, PH.D., UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, RETIRED A Teacher’s Guide to the Signet Classic Edition of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle 2 INTRODUCTION The Jungle by Upton Sinclair was written at the turn of the twentieth century. This period is often painted as one of advancement of the human condition. Sinclair refutes this by unveiling the horrible injustices of Chicago’s meat packing industry as Jurgis Rudkus, his protagonist, discovers the truth about opportunity and prosperity in America. This book is a good choice for eleventh and twelfth grade, junior college, or college students mature enough to understand the purpose of its content. The “hooks” for most students are the human-interest storyline and the graphic descriptions of the meat industry and the realities of immigrant life in America. The teacher’s main role while reading this book with students is to help them understand Sinclair’s purpose. Coordinating the reading of The Jungle with a United States history study of the beginning of the 1900s will illustrate that this novel was not intended as mere entertainment but written in the cause of social reform. As students read, they should be encouraged to develop and express their own ideas about the many political, ethical, and personal issues addressed by Sinclair. This guide includes an overview, which identifies the main characters and summarizes each chapter. -

REVIEW Volume 60 Z No

REVIEW Volume 60 z No. 3 Winter 2018 My Ántonia at 100 Willa Cather REVIEW Volume 60 z No. 3 | Winter 2018 28 35 2 15 22 CONTENTS 1 Letters from the Executive Director, the President 20 Reading My Ántonia Gave My Life a New Roadmap and the Editor Nancy Selvaggio Picchi 2 Sharing Ántonia: A Granddaughter’s Purpose 22 My Grandmother—My Ántonia z Kent Pavelka Tracy Sanford Tucker z Daryl W. Palmer 23 Growing Up with My Ántonia z Fritz Mountford 10 Nebraska, France, Bohemia: “What a Little Circle Man’s My Ántonia, My Grandparents, and Me z Ashley Nolan Olson Experience Is” z Stéphanie Durrans 24 24 Reflection onMy Ántonia z Ann M. Ryan 10 Walking into My Ántonia . z Betty Kort 25 Red Cloud, Then and Now z Amy Springer 11 Talking Ántonia z Marilee Lindemann 26 Libby Larsen’s My Ántonia (2000) z Jane Dressler 12 Farms and Wilderness . and Family z Aisling McDermott 27 How I Met Willa Cather and Her My Ántonia z Petr Just 13 Cather in the Classroom z William Anderson 28 An Immigrant on Immigrants z Richard Norton Smith 14 Each Time, Something New to Love z Trish Schreiber 29 My Two Ántonias z Evelyn Funda 14 Our Reflections onMy Ántonia: A Family Perspective John Cather Ickis z Margaret Ickis Fernbacher 30 Pioneer Days in Webster County z Priscilla Hollingshead 15 Looking Back at My Ántonia z Sharon O’Brien 31 Growing Up in the World of Willa Cather z Kay Hunter Stahly 16 My Ántonia and the Power of Place z Jarrod McCartney 32 “Selah” z Kirsten Frazelle 17 My Ántonia, the Scholarly Edition, and Me z Kari A. -

05 061-081 GORMAN(Net).Indd

The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 28 (2017) Copyright © 2017 Michael Gorman. All rights reserved. This work may be used, with this notice included, for noncommercial purposes. No copies of this work may be distributed, electronically or otherwise, in whole or in part, without permission from the author. Rural Cosmopolitanism and Cultural Imperialism in Willa Cather’s One of Ours Michael GORMAN* INTRODUCTION Among Americans familiar with the novelist Willa Cather (1873–1947), she is best remembered for her depictions of the Great Plains and the pioneers who settled that vast expanse of territory between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains in the nineteenth century. Accordingly, her writing has been both celebrated and dismissed as local color. Even a laudatory biographical sketch from the Willa Cather Archive describes Cather as bringing “American regions to life through her loving portrayals of individuals within local cultures.”1 Yet it is a mistake to view her writing in isolation from global concerns. Cather is a modern writer whose fi ction, even when set in the past, addresses pressing international affairs such as World War I (1914–18) and the events leading up to America’s delayed entrance into that struggle. Unlike Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos, whose writing careers were spawned by World War I, Willa Cather came to maturity as a writer in the decades preceding it, at the crest of America’s colonial ambitions. She began her career as a journalist in 1893—the same year that Frederick Jackson Turner announced his “frontier thesis” and American plantation interests illegally enlisted US Marines to depose the Hawaiian monarch, Queen Liliuokalani. -

The Theory of Moral Sentiments

The Theory of Moral Sentiments Adam Smith Sixth Edition (1790) pΜεταLibriq x y c 2005 Sálvio Marcelo Soares (apply only to edition, not to text) 1st Edition Version a A . Esta obra está disponível para uso privado e individual. Não pode ser vendida nem mantida em sistema de banco de dados, em qualquer forma ou meio, sem prévia autorização escrita do detentor do copyright. Apenas este e as pessoas por ele autorizadas por escrito têm direito de reproduzir esta obra ou transmití-la eletronicamente ou por qualquer outro meio. Published by ΜεταLibri [email protected] Obra editada e publicada no Brasil. São Paulo, May 15, 2006. Contents A PART I Of the P of A S I Of the S of P . p. 4 C.I Of S . 4 C. II Of the Pleasure of mutual Sympathy. 9 C. III Of the manner in which we judge of the propriety or impropriety of the affections of other men, by their concord or dissonance with our own. 11 C. IV The same subject continued . 14 C.V Of the amiable and respectable virtues . 18 S II Of the Degrees of the different Passions which are consistent with Propriety . 22 I. 22 C.I Of the Passions which take their origin from the body . 22 C. II Of those Passions which take their origin from a particular turn or habit of the Imagination. 26 C. III Of the unsocial Passions . 29 C. IV Of the social Passions . 33 C.V Of the selfish Passions. 35 S III Of the Effects of Prosperity and Adversity upon the Judgment of Mankind with regard to the Propriety of Action; and why it is more easy to obtain their Approbation in the one state than in the other . -

Dotre Dame Di5ce-Q)Vasi-5Emper-\/Ictvyi5\/S- Vive-Qvasj-Cras-Tmoieiturvs

^•fl-G^ Cb Dotre Dame Di5ce-q)VASi-5empeR-\/icTvyi5\/s- vive-qvASJ-cRAS-tMOieiTURvs- VOL. XLVII. NOTRE. DAME, INDIANA, MARCH 28, 1914- No. 22. sanctioned, and approved by the Church: The Sixth Station. We distinguish three stages in the develop ment of the Inquisition,—Episcopal, Xegatal, : THEY tore Him with their leaden whips. and Monastic or Papal Inquisition. By virtue With thorns thej' crowned His head. of his office the bishop is the inquisitor in his The .dark blood crimsoned all the ground, diocese. This right the bishop has exercised The snowy rose blushed red; from the veiy first centuries of the Church. And with cursed glee the soldiery It is known as Episcopal Inquisition and is Reviled Him as He bled. as old as the Church. In the iith centurv'", . error seemed to be making way in spite of They drove Him from the sunshine day episcopal vigilance, and the pope named special Along the death-dim road, legates to reinforce the bishops in their efforts With twisted ropes they lashed His flesh. to stamp out heresy. These'were called Legatal And pierced Him with the goad. Inquisitors. But when Gregory IX. saw the And like demons all they cursed His fall immense power wielded by the Dominican Beneath His heavy load. Order against heresy, he reorganized the Ihquisi- • But in the throng one heart beat true. tion with modifications necessary to meet the Her eyes dimmed at the sight, needs of the hour, and put it in the hands of Veronica her kerchief gave the Dominicans. Oi this tribunal, known as the Monastic or Papal Inquisition, we shall now deaL To Jesus in His plight. -

Cambodia's Dirty Dozen

HUMAN RIGHTS CAMBODIA’S DIRTY DOZEN A Long History of Rights Abuses by Hun Sen’s Generals WATCH Cambodia’s Dirty Dozen A Long History of Rights Abuses by Hun Sen’s Generals Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36222 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36222 Cambodia’s Dirty Dozen A Long History of Rights Abuses by Hun Sen’s Generals Map of Cambodia ............................................................................................................... 7 Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Khmer Rouge-era Abuses .........................................................................................................