Peter Taylor's Fictional Memoirs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ellen Glasgow's in This Our Life

69 Ellen Glasgow’s In This Our Life DOI: 10.2478/abcsj-2019-0016 American, British and Canadian Studies, Volume 33, December 2019 Ellen Glasgow’s In This Our Life: “The Betrayals of Life” in the Crumbling Aristocratic South IULIA ANDREEA MILICĂ Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iași, Romania Abstract Ellen Glasgow’s works have received, over time, a mixed interpretation, from sentimental and conventional, to rebellious and insightful. Her novel In This Our Life (1941) allows the reader to have a glimpse of the early twentieth-century South, changed by the industrial revolution, desperately clinging to dead codes, despairing and struggling to survive. The South is reflected through the problems of a family, its sentimentality and vulnerability, but also its cruelty, pretensions, masks and selfishness, trying to find happiness and meaning in a world of traditions and codes that seem powerless in the face of progress. The novel, apparently simple and reduced in scope, offers, in fact, a deep insight into various issues, from complicated family relationships, gender pressures, racial inequality to psychological dilemmas, frustration or utter despair. The article’s aim is to depict, through this novel, one facet of the American South, the “aristocratic” South of belles and cavaliers, an illusory representation indeed, but so deeply rooted in the world’s imagination. Ellen Glasgow is one of the best choices in this direction: an aristocratic woman but also a keen and profound writer, and, most of all, a writer who loved the South deeply, even if she exposed its flaws. Keywords : the South, aristocracy, cavalier, patriarchy, southern belle, women, race, illness The American South is an entity recognizable in the world imagination due to its various representations in fiction, movies, politics, entertainment, advertisements, etc.: white-columned houses, fields of cotton, belles and cavaliers served by benevolent slaves, or, on the contrary, poverty, violence and lynching. -

Fruitful Futility: Land, Body, and Fate in Ellen Glasgow's Barren Ground Katelin R

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in English Department of English 12-2014 Fruitful Futility: Land, Body, and Fate in Ellen Glasgow's Barren Ground Katelin R. Moquin St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Moquin, Katelin R., "Fruitful Futility: Land, Body, and Fate in Ellen Glasgow's Barren Ground" (2014). Culminating Projects in English. 2. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in English by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moquin 1 FRUITFUL FUTILITY: LAND, BODY, AND FATE IN ELLEN GLASGOW’S BARREN GROUND by Katelin Ruth Moquin B.A., Concordia University – Ann Arbor, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree: Master of Arts St. Cloud, Minnesota December, 2014 Moquin 2 FRUITFUL FUTILITY: LAND, BODY, AND FATE IN ELLEN GLASGOW’S BARREN GROUND Katelin Ruth Moquin Through a Cultural Studies lens and with Formalist-inspired analysis, this thesis paper addresses the complexly interwoven elements of land, body, and fate in Ellen Glasgow’s Barren Ground . The introductory chapter is a survey of the critical attention, and lack thereof, Glasgow has received from various literary frameworks. Chapter II summarizes the historical foundations of the South into which Glasgow’s fictionalized South is rooted. -

Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories Jill Sneider Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 5-24-2012 Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories Jill Sneider Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Sneider, Jill, "Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories" (2012). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 728. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/728 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of English Dissertation Examination Committee: Wayne Fields, Chair Naomi Lebowitz Robert Milder George Pepe Richard Ruland Lynne Tatlock Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories By Jill Frank Sneider A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2012 St. Louis, Missouri Copyright by Jill Frank Sneider 2012 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Washington University and the Department of English and American Literature for their flexibility during my graduate education. Their approval of my part-time program made it possible for me to earn a master’s degree and a doctorate. I appreciate the time, advice, and encouragement given to me by Wayne Fields, the Director of my dissertation. He helped me discover new facets to explore every time we met and challenged me to analyze and write far beyond my own expectations. -

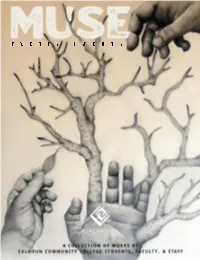

Muse-2020-SINGLES1-1.Pdf

TWENTY TWENTY Self Portrait Heidi Hughes contents Poetry clarity Jillian Oliver ................................................................... 2 I Know You Rayleigh Caldwell .................................................. 2 strawberry Bailey Stuart ........................................................... 3 The Girl Behind the Mirror Erin Gonzalez .............................. 4 exile from neverland Jillian Oliver ........................................... 7 I Once… Erin Gonzalez .............................................................. 7 if ever there should come a time Jillian Oliver ........................ 8 Hello Friend Julia Shelton The Trend Fernanda Carbajal Rodriguez .................................. 9 Love Sonnet Number 666 ½ Jake C. Woodlee .........................11 the end of romance Jillian Oliver ............................................11 What Kindergarten Taught Me Morgan Bryson ..................... 43 Facing Fear Melissa Brown ....................................................... 44 Sharing the Love with Calhoun’s Community ........................... 44 ESSAY Dr. Leigh Ann Rhea J.K. Rowling: The Modern Hero Melissa Brown ................... 12 In the Spotlight: Tatayana Rice Jillian Oliver ......................... 45 Corn Flakes Lance Voorhees .................................................... 15 Student Success Symposium Jillian Oliver .............................. 46 Heroism in The Outcasts of Poker Flat Molly Snoddy .......... 15 In the Spotlight: Chad Kelsoe Amelia Chey Slaton ............... -

THE JUNGLE by VICTORIA ALLEN, M.Ed

A TEACHER’S GUIDE TO THE SIGNET CLASSIC EDITION OF UPTON SINCLAIR’S THE JUNGLE By VICTORIA ALLEN, M.Ed. SERIES EDITORS: W. GEIGER ELLIS, ED.D., UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, EMERITUS and ARTHEA J. S. REED, PH.D., UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, RETIRED A Teacher’s Guide to the Signet Classic Edition of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle 2 INTRODUCTION The Jungle by Upton Sinclair was written at the turn of the twentieth century. This period is often painted as one of advancement of the human condition. Sinclair refutes this by unveiling the horrible injustices of Chicago’s meat packing industry as Jurgis Rudkus, his protagonist, discovers the truth about opportunity and prosperity in America. This book is a good choice for eleventh and twelfth grade, junior college, or college students mature enough to understand the purpose of its content. The “hooks” for most students are the human-interest storyline and the graphic descriptions of the meat industry and the realities of immigrant life in America. The teacher’s main role while reading this book with students is to help them understand Sinclair’s purpose. Coordinating the reading of The Jungle with a United States history study of the beginning of the 1900s will illustrate that this novel was not intended as mere entertainment but written in the cause of social reform. As students read, they should be encouraged to develop and express their own ideas about the many political, ethical, and personal issues addressed by Sinclair. This guide includes an overview, which identifies the main characters and summarizes each chapter. -

Smith Alumnae Quarterly

ALUMNAEALUMNAE Special Issueue QUARTERLYQUARTERLY TriumphantTrT iumphah ntn WomenWomen for the World campaigncac mppaiigngn fortififorortifi eses Smith’sSSmmitith’h s mimmission:sssion: too educateeducac te wwomenommene whowhwho wiwillll cchangehahanngge theththe worldworlrld This issue celebrates a stronstrongerger Smith, where ambitious women like Aubrey MMenarndtenarndt ’’0808 find their pathpathss Primed for Leadership SPRING 2017 VOLUME 103 NUMBER 3 c1_Smith_SP17_r1.indd c1 2/28/17 1:23 PM Women for the WoA New Generationrld of Leaders c2-50_Smith_SP17.indd c2 2/24/17 1:08 PM “WOMEN, WHEN THEY WORK TOGETHER, have incredible power.” Journalist Trudy Rubin ’65 made that statement at the 2012 launch of Smith’s Women for the World campaign. Her words were prophecy. From 2009 through 2016, thousands of Smith women joined hands to raise a stunning $486 million. This issue celebrates their work. Thanks to them, promising women from around the globe will continue to come to Smith to fi nd their voices and their opportunities. They will carry their education out into a world that needs their leadership. SMITH ALUMNAE QUARTERLY Special Issue / Spring 2017 Amber Scott ’07 NICK BURCHELL c2-50_Smith_SP17.indd 1 2/24/17 1:08 PM In This Issue • WOMEN HELPING WOMEN • A STRONGER CAMPUS 4 20 We Set Records, Thanks to You ‘Whole New Areas of Strength’ In President’s Perspective, Smith College President The Museum of Art boasts a new gallery, two new Kathleen McCartney writes that the Women for the curatorships and some transformational acquisitions. World campaign has strengthened Smith’s bottom line: empowering exceptional women. 26 8 Diving Into the Issues How We Did It Smith’s four leadership centers promote student engagement in real-world challenges. -

REVIEW Volume 60 Z No

REVIEW Volume 60 z No. 3 Winter 2018 My Ántonia at 100 Willa Cather REVIEW Volume 60 z No. 3 | Winter 2018 28 35 2 15 22 CONTENTS 1 Letters from the Executive Director, the President 20 Reading My Ántonia Gave My Life a New Roadmap and the Editor Nancy Selvaggio Picchi 2 Sharing Ántonia: A Granddaughter’s Purpose 22 My Grandmother—My Ántonia z Kent Pavelka Tracy Sanford Tucker z Daryl W. Palmer 23 Growing Up with My Ántonia z Fritz Mountford 10 Nebraska, France, Bohemia: “What a Little Circle Man’s My Ántonia, My Grandparents, and Me z Ashley Nolan Olson Experience Is” z Stéphanie Durrans 24 24 Reflection onMy Ántonia z Ann M. Ryan 10 Walking into My Ántonia . z Betty Kort 25 Red Cloud, Then and Now z Amy Springer 11 Talking Ántonia z Marilee Lindemann 26 Libby Larsen’s My Ántonia (2000) z Jane Dressler 12 Farms and Wilderness . and Family z Aisling McDermott 27 How I Met Willa Cather and Her My Ántonia z Petr Just 13 Cather in the Classroom z William Anderson 28 An Immigrant on Immigrants z Richard Norton Smith 14 Each Time, Something New to Love z Trish Schreiber 29 My Two Ántonias z Evelyn Funda 14 Our Reflections onMy Ántonia: A Family Perspective John Cather Ickis z Margaret Ickis Fernbacher 30 Pioneer Days in Webster County z Priscilla Hollingshead 15 Looking Back at My Ántonia z Sharon O’Brien 31 Growing Up in the World of Willa Cather z Kay Hunter Stahly 16 My Ántonia and the Power of Place z Jarrod McCartney 32 “Selah” z Kirsten Frazelle 17 My Ántonia, the Scholarly Edition, and Me z Kari A. -

05 061-081 GORMAN(Net).Indd

The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 28 (2017) Copyright © 2017 Michael Gorman. All rights reserved. This work may be used, with this notice included, for noncommercial purposes. No copies of this work may be distributed, electronically or otherwise, in whole or in part, without permission from the author. Rural Cosmopolitanism and Cultural Imperialism in Willa Cather’s One of Ours Michael GORMAN* INTRODUCTION Among Americans familiar with the novelist Willa Cather (1873–1947), she is best remembered for her depictions of the Great Plains and the pioneers who settled that vast expanse of territory between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains in the nineteenth century. Accordingly, her writing has been both celebrated and dismissed as local color. Even a laudatory biographical sketch from the Willa Cather Archive describes Cather as bringing “American regions to life through her loving portrayals of individuals within local cultures.”1 Yet it is a mistake to view her writing in isolation from global concerns. Cather is a modern writer whose fi ction, even when set in the past, addresses pressing international affairs such as World War I (1914–18) and the events leading up to America’s delayed entrance into that struggle. Unlike Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos, whose writing careers were spawned by World War I, Willa Cather came to maturity as a writer in the decades preceding it, at the crest of America’s colonial ambitions. She began her career as a journalist in 1893—the same year that Frederick Jackson Turner announced his “frontier thesis” and American plantation interests illegally enlisted US Marines to depose the Hawaiian monarch, Queen Liliuokalani. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Ghosts and Flesh, Vinegar and Wine: Ten Recent Novels Vernon Young

New Mexico Quarterly Volume 22 | Issue 3 Article 16 1952 Ghosts and Flesh, Vinegar and Wine: Ten Recent Novels Vernon Young Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq Recommended Citation Young, Vernon. "Ghosts and Flesh, Vinegar and Wine: Ten Recent Novels." New Mexico Quarterly 22, 3 (1952). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq/vol22/iss3/16 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Mexico Press at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Quarterly by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Young: Ghosts and Flesh, Vinegar and Wine: Ten Recent Novels BOOKS and COMMENT Vernon Young GHOSTS AND FLESH, VINEGAR AND WINE: TEN RECENT NOVELS f 0- NG these novels,l chosen for review with no careful pre meditation of subject, The Lighted Cities is easily sover A. eign by possession of those ruling attributes of matured fiction-worldliness, imagination critically conditioned, a feeling for life convergent with a feeling for written language. Specifical ly, the direct way of asserting Ernest Frost's quality is to postulate Graham Greene, shorn of clerical masochism, rising to the full limits of his promise. Writing with verve and lyric nervousness of a cauldron of unholy loves in present-day London, Frost sounds the extreme notes that all of us can read in the living scale but can rarely harmonize: the notes of tenderness, of revulsion, of de~pair, of cold clarity, of hope and bewilderment. Frost is on the side of life but he is hard at the core; as a result, his insights and characterizations emanate an oblique beauty of expression which is best appreciated by generous quotation of his theme and variations: WeB, it's curious, seel A sort of deranged reasonableness about people living in cities which are lighted up for the peace, but it isn't really peace, and everyone's still at war within themselves. -

Award Winners

Award Winners Agatha Awards 1992 Boot Legger’s Daughter 2005 Dread in the Beast Best Contemporary Novel by Margaret Maron by Charlee Jacob (Formerly Best Novel) 1991 I.O.U. by Nancy Pickard 2005 Creepers by David Morrell 1990 Bum Steer by Nancy Pickard 2004 In the Night Room by Peter 2019 The Long Call by Ann 1989 Naked Once More Straub Cleeves by Elizabeth Peters 2003 Lost Boy Lost Girl by Peter 2018 Mardi Gras Murder by Ellen 1988 Something Wicked Straub Byron by Carolyn G. Hart 2002 The Night Class by Tom 2017 Glass Houses by Louise Piccirilli Penny Best Historical Mystery 2001 American Gods by Neil 2016 A Great Reckoning by Louise Gaiman Penny 2019 Charity’s Burden by Edith 2000 The Traveling Vampire Show 2015 Long Upon the Land Maxwell by Richard Laymon by Margaret Maron 2018 The Widows of Malabar Hill 1999 Mr. X by Peter Straub 2014 Truth be Told by Hank by Sujata Massey 1998 Bag of Bones by Stephen Philippi Ryan 2017 In Farleigh Field by Rhys King 2013 The Wrong Girl by Hank Bowen 1997 Children of the Dusk Philippi Ryan 2016 The Reek of Red Herrings by Janet Berliner 2012 The Beautiful Mystery by by Catriona McPherson 1996 The Green Mile by Stephen Louise Penny 2015 Dreaming Spies by Laurie R. King 2011 Three-Day Town by Margaret King 1995 Zombie by Joyce Carol Oates Maron 2014 Queen of Hearts by Rhys 1994 Dead in the Water by Nancy 2010 Bury Your Dead by Louise Bowen Holder Penny 2013 A Question of Honor 1993 The Throat by Peter Straub 2009 The Brutal Telling by Louise by Charles Todd 1992 Blood of the Lamb by Penny 2012 Dandy Gilver and an Thomas F.