Impact of Endangered Animal Protection Rights, Policies, and Practices on Zoonotic Disease Spread

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Get Ready to Rumble! 06 Comments 08 Diversions 10 Arts & Culture Uniter.Ca 18 Listings

THE I SSUE The university of Winnipeg student weekly 222006/03/16 VOLUME 60 INSIDE 02 News GET READY TO RUMBLE! 06 Comments 08 Diversions 10 Arts & Culture uniter.ca 18 Listings » UWSA ELECTIONS 2006 21 Features 22 Sports ON THE WEB [email protected] » E-MAIL SSUE 22 I VOL. 60 2006 16, H C R A M ELECTION 2006 02 MAKE YOUR VOTE COUNT MARCH 20 -23 SENSE MEMORY AND PHOTOGRAPHY 12 SARAH CRAWLEY CASTS OFF THE SHACKLES OF REALITY INNIPEG STUDENTINNIPEG WEEKLY W MEDIA DEMONSTRATES DIALOGUE 21 BUT HAS THE IMAGE OF WOMEN IN MEDIA REALLY CHANGED? BOMBERS SPRING CLEAN 23 WILL 2006 BE A BETTER SEASON? HE UNIVERSITY OF T ♼ March 16, 2006 The Uniter contact: [email protected] SENIOR EDITOR: LEIGHTON KLASSEN NEWS EDITOR: DEREK LESCHASIN 02 NEWS E-MAIL: [email protected] E-MAIL: [email protected] UNITER STAFF UWSA Elections in Full Swing INCUMBENTS CHALLENGED ON TACTICS Managing Editor » Jo Snyder 01 [email protected] 02 Business Coordinator & Offi ce Manager » James D. Patterson [email protected] LINDSEY WIEBE bulk food sales, new computer peting for the position of Vice- kiosks to reduce lines at the Petrifi ed President Student Services. NEWS PRODUCTION EDITOR » Sole used Belik’s ideas include free web host- 03 Derek Leschasin [email protected] bookstore, locked compounds bike ing for student groups, an increased foot he University of Winnipeg storage, and an online carpool and patrol presence, and skills workshops 04 SENIOR EDITOR » Leighton Klassen Students’ Association election is [email protected] parking registry. on campus for things like cooking, silk- T under way, and it’s shaping up to Another item on her agenda is ad- screening and bike repair. -

The Sexual Politics of Meat by Carol J. Adams

THE SEXUAL POLITICS OF MEAT A FEMINISTVEGETARIAN CRITICAL THEORY Praise for The Sexual Politics of Meat and Carol J. Adams “A clearheaded scholar joins the ideas of two movements—vegetari- anism and feminism—and turns them into a single coherent and moral theory. Her argument is rational and persuasive. New ground—whole acres of it—is broken by Adams.” —Colman McCarthy, Washington Post Book World “Th e Sexual Politics of Meat examines the historical, gender, race, and class implications of meat culture, and makes the links between the prac tice of butchering/eating animals and the maintenance of male domi nance. Read this powerful new book and you may well become a vegetarian.” —Ms. “Adams’s work will almost surely become a ‘bible’ for feminist and pro gressive animal rights activists. Depiction of animal exploita- tion as one manifestation of a brutal patriarchal culture has been explored in two [of her] books, Th e Sexual Politics of Meat and Neither Man nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals. Adams argues that factory farming is part of a whole culture of oppression and insti- tutionalized violence. Th e treatment of animals as objects is parallel to and associated with patriarchal society’s objectifi cation of women, blacks, and other minorities in order to routinely exploit them. Adams excels in constructing unexpected juxtapositions by using the language of one kind of relationship to illuminate another. Employing poetic rather than rhetorical techniques, Adams makes powerful connec- tions that encourage readers to draw their own conclusions.” —Choice “A dynamic contribution toward creating a feminist/animal rights theory.” —Animals’ Agenda “A cohesive, passionate case linking meat-eating to the oppression of animals and women . -

4Th MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE

th 4 MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE MÉXICO, 17 TO 24 JANUARY, 2018 SOCIAL PROGRAMME: ROYAL PEDREGAL HOTEL ACADEMIC PROGRAMME: NATIONAL AUTONOMOUS UNIVERSITY OF MEXICO Auditorio Alfonso Caso and Anexos de la Facultad de Derecho FINAL PROGRAMME (Online version linked to abstracts. Download PDF here) 1/47 All delegates please note: 1. Presentation slots may have needed to be moved by the organisers, and may appear in a different place from that of the final printed programme. Please consult the schedule located in the Conference Programme upon arrival at the Conference for your presentation time. 2. Please note that presenters have to ensure the following times for presentation to allow for adequate time for questions from the floor and smooth transition of sessions. Delegates must not stray from their allocated 20 minutes. Further, delegates are welcome to move within sessions, therefore presenters MUST limit their talk to the allocated time. Therefore, Q&A will be AFTER each talk, and NOT at the end of the three presentations. Plenary and Invited Talks – 45 min. presentation and 15 min. discussion (Q&A). 3. For panels, each panellist must stick strictly to a 10 minute time frame, before discussion with the floor commences. 4. Note that co-authors may be presenting at the conference in place of, or with the main author. For all co-authors, delegates are advised to consult the Conference Abstracts link on the Minding Animals website. Use of the term et al is provided where there is more than two authors of an abstract. 5. Moderator notes will be available at all front desks in tutorial rooms, along with Time Sheets (5, 3 and 1 minute Left). -

Why Vegan? Rev

THE TRANSFORMATION OF ANIMALS INTO FOOD Many people believe that animals raised for food must be treated well because sick or dead animals would be of no use to agribusiness. This is not true. INDUSTRIALIZED CRUELTY: FACTORY FARMING The competition to produce inexpensive meat, eggs, and dairy products has led animal agribusiness to treat animals as objects and commodities. The worldwide trend is to replace small family farms with “factory farms”—large warehouses where animals are confined in crowded cages or pens or in restrictive stalls. “U.S. society is extremely naive about the nature of agricultural production. “[I]f the public knew more about the way in which agricultural and animal production infringes on animal welfare, the outcry would be louder.” BERNARD E. ROLLIN, PhD Farm Animal Welfare, Iowa State University Press, 2003 Hens in crowded cages suffer severe feather loss. Bernard Rollin, PhD, explains that it is “more economically efficient to put a greater number of birds into each cage, accepting lower productivity per bird but greater productivity per cage… individual animals may ‘produce,’ for example gain weight, in part because they are immobile, yet suffer because of the inability to move.… Chickens are cheap, cages are expensive.” 1 In a November 1993 article in favor of reducing space from 8 to 6 square feet per pig, industry journal National Hog 2 Farmer advised, “Crowding pigs pays.” Inside a broiler house. Birds Virtually all U.S. birds raised for food are factory farmed. 2 Inside the densely populated buildings, enormous amounts of waste accumulate. The result- ing ammonia levels commonly cause painful burns to the birds’ skin, eyes, and respiratory tracts. -

Evaluating the Slaughter Techniques in Cattle

Influence of conventional and Kosher slaughter techniques in cattle on carcass and meat quality By BABATUNDE AGBENIGA B. Inst. Agrar. (Hons). Food Production and Processing University of Pretoria Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree M.Sc. (Agric) Meat Science In the Department of Animal and Wildlife Sciences University of Pretoria Pretoria 2011 Supervisor: Prof. E.C. Webb. © University of Pretoria DECLARATION I declare that this thesis for the degree M.Sc. (Agric) Meat Science at the University of Pretoria has not been submitted by me for a degree at any other University Babatunde Agbeniga November, 2011 CONTENTS Acknowledgements i List of abbreviation ii List of figures iv List of tables v Abstract vi Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Literature review 4 2.1 Slaughter 4 2.2 Treatment of animals prior to slaughter 9 2.3 Effects of stress on meat quality 10 2.4 Types of muscles, their structure and composition, location and 12 metabolism 2.5 Blood and body fluid 24 2.6 Slaughter methods in international abattoirs 25 2.7 Legislation and regulations guiding animal slaughter 25 2.8 The standard slaughter methods and their effects on meat and 26 carcass quality 2.9 Kosher slaughter method and its principles 35 2.10 Effects of the Kosher slaughter technique on meat and carcass 39 quality parameters 2.11 Electrical stimulation of carcasses 43 Chapter 3: Materials and methods 45 3.1 Pre-slaughter processes 45 3.2 Slaughter processes 45 3.3 Sample collection 55 3.4 Methods 55 3.5 Statistical analyses 57 Chapter -

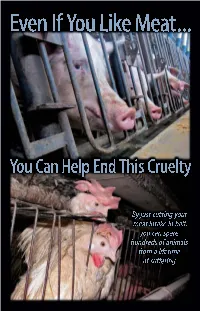

Even If You Like Meat Leaflet

Oppose the Cruelties of Factory Farming Thank you for accepting this booklet. As you read on, please bear in mind that opposing the cruelties of factory farming is not an all-or-nothing proposition: By simply eating less meat, you can help prevent farmed animals from suffering. “When we picture a farm, we picture scenes from Old MacDonald and Charlotte’s Web, not warehouses with , chickens.… When we look, it’s shocking. Our rural idylls have been transformed into stinking factories.” The Los Angeles Times “The High Price of Cheap Food,” 1/21/04 Above: The average breeding sow spends most of her life in a two-foot-wide stall, without enough room to turn around;1 others (below) live in crowded pens. Today’s egg-laying hens are warehoused inside battery cages. Most U.S. livestock production has shifted from small family farms to factory farms— huge ware houses where the animals are confined in crowded cages or pens or in restrictive stalls. Due to consumer demand for inexpensive meat, eggs, and dairy, these animals are treated as mere objects rather than individuals who can suffer. Hidden from public view, the cruelty that occurs on factory farms is easy to ignore. But more and more people are becoming aware of how farmed animals are treated 2 and deciding that it’s too cruel to support. “In my opinion, if most urban meat eaters were to visit an industrial broiler house, to see how the birds are raised, and could see the birds being ‘harvested’ and then being ‘processed’ in a poultry processing plant, they would not be impressed and some, perhaps many of them would swear off eating chicken and perhaps all meat. -

20 May 2015 Thierry Meeùs Owner Mini-Europe Via E-Mail

20 May 2015 Thierry Meeùs Owner Mini-Europe Via e-mail: [email protected] Dear Mr Meeùs, I am writing on behalf of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) UK and AnimaNaturalis, a Spanish animal rights organisation – along with our hundreds of thousands of supporters throughout Europe – to urge you to update the depiction of Spain in the Mini-Europe park from a bullring to something more representative of modern Spanish culture such as Seville's Plaza de España. Bullfighting is animal abuse, plain and simple. In the ring, the bull has swords plunged into his neck, back and body again and again until blood pours from his wounds and mouth. He is terrified and in excruciating pain. He doesn't want to die, but he can't run away, and soon he won't even be able to stand up. After falling to the floor from exhaustion and massive blood loss, he can only watch as a knife rips into his spinal cord to kill him. This is the experience of bulls killed in Spanish bullfights. Opposition to bullfighting in Spain is already vast and mounting. According to a recent survey, 76 per cent of Spaniards show no interest in bullfights, up from 56 per cent in the '80s, and 76 per cent oppose the use of public funds to support the industry. The entire region of Catalonia is just one of the many locales in Spain that have banned bullfighting for good. The loss-incurring bloodsport of bullfighting could not continue without public subsidies paid by taxpayers. -

Vegetarian Starter Kit You from a Family Every Time Hold in Your Hands Today

inside: Vegetarian recipes tips Starter info Kit everything you need to know to adopt a healthy and compassionate diet the of how story i became vegetarian Chinese, Indian, Thai, and Middle Eastern dishes were vegetarian. I now know that being a vegetarian is as simple as choosing your dinner from a different section of the menu and shopping in a different aisle of the MFA’s Executive Director Nathan Runkle. grocery store. Though the animals were my initial reason for Dear Friend, eliminating meat, dairy and eggs from my diet, the health benefi ts of my I became a vegetarian when I was 11 years old, after choice were soon picking up and taking to heart the content of a piece apparent. Coming of literature very similar to this Vegetarian Starter Kit you from a family every time hold in your hands today. plagued with cancer we eat we Growing up on a small farm off the back country and heart disease, roads of Saint Paris, Ohio, I was surrounded by which drastically cut are making animals since the day I was born. Like most children, short the lives of I grew up with a natural affi nity for animals, and over both my mother and time I developed strong bonds and friendships with grandfather, I was a powerful our family’s dogs and cats with whom we shared our all too familiar with home. the effect diet can choice have on one’s health. However, it wasn’t until later in life that I made the connection between my beloved dog, Sadie, for whom The fruits, vegetables, beans, and whole grains my diet I would do anything to protect her from abuse and now revolved around made me feel healthier and gave discomfort, and the nameless pigs, cows, and chickens me more energy than ever before. -

The World Peace Diet

THE WORLD PEACE DIET Eating for Spiritual Health and Social Harmony WILL TUTTLE, Ph.D. Lantern Books • New York A Division of Booklight Inc. 2005 Lantern Books One Union Square West, Suite 201 New York, NY 10003 Copyright Will Tuttle, 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of Lantern Books. Printed in the United States of America Cover painting by Madeleine W. Tuttle Cover design by Josh Hooten Extensive quotations have been taken from Slaughterhouse: The Shocking Story of Greed, Neglect, and Inhumane Treatment Inside the U.S. Meat Industry by Gail A. Eisnitz (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1997). Copyright 1997 by The Humane Farming Association. Reprinted with permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tuttle, Will M. The world peace diet: eating for spiritual health and social harmony / Will Tuttle. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-59056-083-3 (alk. paper) 1. Food—Social aspects. 2. Food—Philosophy. 3. Diet—Moral and eth- ical aspects. I. Title. RA601.T88 2005 613.2—dc22 2005013690 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ĺĺ I am grateful to the many people who have helped along the way, contributing their insights and energy to the process of creating this book. My heartfelt appreciation to those who read the manuscript at some stage and offered helpful comments, particularly Judy Carman, Evelyn Casper, Reagan Forest, Lynn Gale, Cheryl Maietta, Laura Remmy, Veda Stram, Beverlie Tuttle, Ed Tuttle, and Madeleine Tuttle. -

State of Animals Ch 06

Progress in Livestock Handling and Slaughter Techniques 6CHAPTER in the United States, 1970–2000 Temple Grandin have worked as a consultant to the reaction to CO2 gas. Some studies allows a plant to engage in interstate meat industry since the early show evidence of aversion; others do commerce, regardless of who the I 1970s. I’ve been in more than 300 not (Forslid 1987; Grandin 1988a; buyer is.) The act was also extended slaughter plants in the United States, Dodman 1977; Raj et al. 1997). My to cover the handling of animals prior Canada, Mexico, Europe, Australia, own observations lead me to believe to slaughter while they were on the New Zealand, and South America. that some pigs can be anesthetized premises of the slaughter plant. Cruel During the course of my career, I’ve peacefully with CO2 while others fran- practices such as dragging conscious, seen many changes take place, but tically attempt to escape when they crippled, non-ambulatory (downed) I’m going to focus in this paper on my first smell the gas (Grandin 1988a). animals were prohibited. However, work to improve conditions for the Genetic factors appear to influence the handling of animals for ritual slaughter of cattle and calves and the reaction. Purebred Yorkshire pigs slaughter was—and is—exempt, as is later address transport and other ani- are anesthetized peacefully (Forslid the slaughter of poultry. In ritual mal-handling issues. 1987), for example, while other slaughter, both kosher (Jewish) and The U.S. Humane Slaughter Act, strains become agitated prior to halal (Muslim), the throat of an passed in 1958, required that all meat being anesthetized (Grandin 1988a; unstunned animal is cut. -

WHY VEG A5 Flyer.Indd

Boycott Cruelty Go Vegan! TURNING ANIMALS INTO FOOD Many people believe (and hope) that animals raised for food for humans must be very well treated because sick, diseased or dead animals would be of no use to agribusiness. But this is not true. FACTORY FARMING= INDUSTRIALISED CRUELTY The pressure to produce inexpensive beef, chicken, pork, veal, fish, eggs, milk and dairy products has led modern farming to treat animals as mere commodities or machines. There is a trend worldwide to replace small family farms with intensive, industrialised, factory farms. The philosophy of mass production is what lies behind it all. “...if the public knew more about the way in which agricultural and animal production infringes on animal welfare, the outcry would be louder.” BERNARD E. ROLLIN, PhD Farm Animal Welfare, Iowa State University Press, 1995. Bernard Rollin is author of more than 150 papers and 10 books on ethics and animal science. Hens in crowded cages suffer severe feather loss. “The life of an animal in a factory farm is characterised by acute deprivation, stress, and disease. Hundreds of millions of animals are forced to live in cages just barely larger than their own bodies. While one species may be caged alone without any social contact, another species may be crowded so tightly together that they fall prey to stress-induced cannibalism… the victims of factory farms exist in a relentless state of distress.” Humane Farming Association: 2 The Dangers of Factory Farming Inside a broiler house. Broiler Chickens Virtually all chickens in Australia raised for meat are factory farmed. -

Vibeke Final Version

The Changing Place of Animals in Post-Franco Spain with particular reference to Bullfighting, Popular Festivities, and Pet-keeping. Vibeke Hansen A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology University of Essex October 2015 Abstract This is a thesis about the changing place of animals in post-Franco Spain, with particular reference to bullfighting, popular festivities, and pet-keeping. The thesis argues that since the ‘transition’ to democracy (1975-1982), which made Spain one of the most liberal social-democratic states in Europe, there have been several notable developments in human-animal relations. In some important respects, Spain has begun to shed its unenviable reputation for cruelty towards animals. Three important changes have occurred. First, bullfighting (corridas) has been banned in the Canary Islands (1991) and in Catalonia (2010). In addition, numerous municipalities have declared themselves against it. Second, although animals are still widely ‘abused’ and killed (often illegally) in local festivities, many have gradually ceased to use live animals, substituting either dead ones or effigies, and those that continue to use animals are subject to increasing legal restrictions. Third, one of the most conspicuous changes has been the growth in popularity of urban pet-keeping, together with the huge expansion of the market for foods, accessories and services - from healthy diets to cemeteries. The thesis shows that the character of these changing human-animal relations, and the resistance