Memories of American Anarchism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis W/ Corrections

Renouncing the Le-: Working-class conserva7sm in France, 1930-1939 Joseph Starkey A Thesis submi+ed for the Degree of PhD at Cardiff University 2014 Abstract Histories of the working class in France have largely ignored the existence of working-class conservaGsm. This is parGcularly true of histories of the interwar period. Yet, there were an array of Catholic and right-wing groups during these years that endeavoured to bring workers within their orbit. Moreover, many workers judged that their interests were be+er served by these groups. This thesis explores the parGcipaGon of workers in Catholic and right-wing groups during the 1930s. What did these groups claim to offer workers within the wider context of their ideological goals? In which ways did conservaGve workers understand and express their interests, and why did they idenGfy the supposed ‘enemies of the leT’ as the best means of defending them? What was the daily experience of conservaGve workers like, and how did this experience contribute to the formaGon of ‘non-leT’ poliGcal idenGGes? These quesGons are addressed in a study of the largest Catholic and right-wing groups in France during the 1930s. This thesis argues that, during a period of leT-wing ascendancy, these groups made the recruitment of workers a top priority. To this end, they harnessed parGcular elements of mass poliGcal culture and adapted them to their own ideological ends. However, the ideology of these groups did not simply reflect the interests of the workers that supported them. This thesis argues that the interests of conservaGve workers were a raGonal and complex product of their own experience. -

EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, and the “AMERICAN DREAM” by Christina Samons

AN AMERICA THAT COULD BE: EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, AND THE “AMERICAN DREAM” By Christina Samons The so-called “Gilded Age,” 1865-1901, was a period in American his tory characterized by great progress, but also of great turmoil. The evolving social, political, and economic climate challenged the way of life that had existed in pre-Civil War America as European immigration rose alongside the appearance of the United States’ first big businesses and factories.1 One figure emerges from this era in American history as a forerunner of progressive thought: Emma Goldman. Responding, in part, to the transformations that occurred during the Gilded Age, Goldman gained notoriety as an outspoken advocate of anarchism in speeches throughout the United States and through published essays and pamphlets in anarchist newspapers. Years later, she would synthe size her ideas in collections of essays such as Anarchism and Other Essays, first published in 1917. The purpose of this paper is to contextualize Emma Goldman’s anarchist theory by placing it firmly within the economic, social, and 1 Alan M. Kraut, The Huddled Masses: The Immigrant in American Society, 1880 1921 (Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2001), 14. 82 Christina Samons political reality of turn-of-the-twentieth-century America while dem onstrating that her theory is based in a critique of the concept of the “American Dream.” To Goldman, American society had drifted away from the ideal of the “American Dream” due to the institutionalization of exploitation within all aspects of social and political life—namely, economics, religion, and law. The first section of this paper will give a brief account of Emma Goldman’s position within American history at the turn of the twentieth century. -

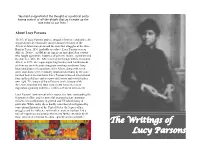

The Writings of Lucy Parsons

“My mind is appalled at the thought of a political party having control of all the details that go to make up the sum total of our lives.” About Lucy Parsons The life of Lucy Parsons and the struggles for peace and justice she engaged provide remarkable insight about the history of the American labor movement and the anarchist struggles of the time. Born in Texas, 1853, probably as a slave, Lucy Parsons was an African-, Native- and Mexican-American anarchist labor activist who fought against the injustices of poverty, racism, capitalism and the state her entire life. After moving to Chicago with her husband, Albert, in 1873, she began organizing workers and led thousands of them out on strike protesting poor working conditions, long hours and abuses of capitalism. After Albert, along with seven other anarchists, were eventually imprisoned or hung by the state for their beliefs in anarchism, Lucy Parsons achieved international fame in their defense and as a powerful orator and activist in her own right. The impact of Lucy Parsons on the history of the American anarchist and labor movements has served as an inspiration spanning now three centuries of social movements. Lucy Parsons' commitment to her causes, her fame surrounding the Haymarket affair, and her powerful orations had an enormous influence in world history in general and US labor history in particular. While today she is hardly remembered and ignored by conventional histories of the United States, the legacy of her struggles and her influence within these movements have left a trail of inspiration and passion that merits further attention by all those interested in human freedom, equality and social justice. -

The Spanish Anarchists: the Heroic Years, 1868-1936

The Spanish Anarchists THE HEROIC YEARS 1868-1936 the text of this book is printed on 100% recycled paper The Spanish Anarchists THE HEROIC YEARS 1868-1936 s Murray Bookchin HARPER COLOPHON BOOKS Harper & Row, Publishers New York, Hagerstown, San Francisco, London memoria de Russell Blackwell -^i amigo y mi compahero Hafold F. Johnson Library Ceirtef' "ampsliire College Anrteret, Massachusetts 01002 A hardcover edition of this book is published by Rree Life Editions, Inc. It is here reprinted by arrangement. THE SPANISH ANARCHISTS. Copyright © 1977 by Murray Bookchin. AH rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission except in the case ofbrief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address ftee Life Editions, Inc., 41 Union Square West, New York, N.Y. 10003. Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published 1978 ISBN: 0-06-090607-3 78 7980 818210 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 21 Contents OTHER BOOKS BY MURRAY BOOKCHIN Introduction ^ Lebensgefahrliche, Lebensmittel (1955) Prologue: Fanelli's Journey ^2 Our Synthetic Environment (1%2) I. The "Idea" and Spain ^7 Crisis in Our Qties (1965) Post-Scarcity Anarchism (1971) BACKGROUND MIKHAIL BAKUNIN 22 The Limits of the Qty (1973) Pour Une Sodete Ecologique (1976) II. The Topography of Revolution 32 III. The Beginning THE INTERNATIONAL IN SPAIN 42 IN PREPARATION THE CONGRESS OF 1870 51 THE LIBERAL FAILURE 60 T'he Ecology of Freedom Urbanization Without Cities IV. The Early Years 67 PROLETARIAN ANARCHISM 67 REBELLION AND REPRESSION 79 V. -

CHAPTER VI Individualism and Futurism: Compagni in Milan

I Belong Only to Myself: The Life and Writings of Leda Rafanelli Excerpt from: CHAPTER VI Individualism and Futurism: Compagni in Milan ...Tracking back a few years, Leda and her beau Giuseppe Monanni had been invited to Milan in 1908 in order to take over the editorship of the newspaper The Human Protest (La Protesta Umana) by its directors, Ettore Molinari and Nella Giacomelli. The anarchist newspaper with the largest circulation at that time, The Human Protest was published from 1906–1909 and emphasized individual action and rebellion against institutions, going so far as to print articles encouraging readers to occupy the Duomo, Milan’s central cathedral.3 Hence it was no surprise that The Human Protest was subject to repeated seizures and the condemnations of its editorial managers, the latest of whom—Massimo Rocca (aka Libero Tancredi), Giovanni Gavilli, and Paolo Schicchi—were having a hard time getting along. Due to a lack of funding, editorial activity for The Human Protest was indefinitely suspended almost as soon as Leda arrived in Milan. She nevertheless became close friends with Nella Giacomelli (1873– 1949). Giacomelli had started out as a socialist activist while working as a teacher in the 1890s, but stepped back from political involvement after a failed suicide attempt in 1898, presumably over an unhappy love affair.4 She then moved to Milan where she met her partner, Ettore Molinari, and turned towards the anarchist movement. Her skepticism, or perhaps burnout, over the ability of humans to foster social change was extended to the anarchist movement, which she later claimed “creates rebels but doesn’t make anarchists.”5 Yet she continued on with her literary initiatives and support of libertarian causes all the same. -

The Surreal Voice in Milan's Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 2-2021 The Surreal Voice in Milan's Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi Jason Collins The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4143 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE SURREALIST VOICE IN MILAN’S ITINERANT POETICS: DELIO TESSA TO FRANCO LOI by JASON M. COLLINS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2021 i © 2021 JASON M. COLLINS All Rights Reserved ii The Surreal Voice in Milan’s Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi by Jason M. Collins This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy _________________ ____________Paolo Fasoli___________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _________________ ____________Giancarlo Lombardi_____ Date Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Paolo Fasoli André Aciman Hermann Haller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Surreal Voice in Milan’s Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi by Jason M. Collins Advisor: Paolo Fasoli Over the course of Italy’s linguistic history, dialect literature has evolved a s a genre unto itself. -

Anarchist Movements in Tampico & the Huaste

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Peripheries of Power, Centers of Resistance: Anarchist Movements in Tampico & the Huasteca Region, 1910-1945 A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Latin American Studies (History) by Kevan Antonio Aguilar Committee in Charge: Professor Christine Hunefeldt, Co-Chair Professor Michael Monteon, Co-Chair Professor Max Parra Professor Eric Van Young 2014 The Thesis of Kevan Antonio Aguilar is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii DEDICATION: For my grandfather, Teodoro Aguilar, who taught me to love history and to remember where I came from. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………..…………..…iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………………...…iv Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………….v List of Figures………………………………………………………………………….…vi Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………vii Abstract of the Thesis…………………………………………………………………….xi Introduction……………………………………………………………………………......1 Chapter 1: Geography & Peripheral Anarchism in the Huasteca Region, 1860-1917…………………………………………………………….10 Chapter 2: Anarchist Responses to Post-Revolutionary State Formations, 1918-1930…………………………………………………………….60 Chapter 3: Crisis & the Networks of Revolution: Regional Shifts towards International Solidarity Movements, 1931-1945………………95 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….......126 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………129 v LIST -

Justice Crucified* a Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography of the Sacco and Vanzetti Case

Differentia: Review of Italian Thought Number 8 Combined Issue 8-9 Spring/Autumn Article 21 1999 Remember! Justice Crucified: A Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography Gil Fagiani Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia Recommended Citation Fagiani, Gil (1999) "Remember! Justice Crucified: A Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography," Differentia: Review of Italian Thought: Vol. 8 , Article 21. Available at: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia/vol8/iss1/21 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Academic Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Differentia: Review of Italian Thought by an authorized editor of Academic Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Remember! Justice Crucified* A Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography of the Sacco and Vanzetti Case Gil Fagiani ____ _ The Enduring Legacy of the Sacco and Vanzetti Case Two Italian immigrants, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, became celebrated martyrs in the struggle for social justice and politi cal freedom for millions of Italian Americans and progressive-minded people throughout the world. Having fallen into a police trap on May 5, 1920, they eventually were indicted on charges of participating in a payroll robbery in South Braintree, Massachusetts in which a paymas ter and his guard were killed. After an unprecedented international campaign, they were executed in Boston on August 27, 1927. Intense interest in the case stemmed from a belief that Sacco and Vanzetti had not been convicted on the evidence but because they were Italian working-class immigrants who espoused a militant anarchist creed. -

Anarchy! an Anthology of Emma Goldman's Mother Earth

U.S. $22.95 Political Science anarchy ! Anarchy! An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s MOTHER EARTH (1906–1918) is the first An A n t hol o g y collection of work drawn from the pages of the foremost anarchist journal published in America—provocative writings by Goldman, Margaret Sanger, Peter Kropotkin, Alexander Berkman, and dozens of other radical thinkers of the early twentieth cen- tury. For this expanded edition, editor Peter Glassgold contributes a new preface that offers historical grounding to many of today’s political movements, from liber- tarianism on the right to Occupy! actions on the left, as well as adding a substantial section, “The Trial and Conviction of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman,” which includes a transcription of their eloquent and moving self-defense prior to their imprisonment and deportation on trumped-up charges of wartime espionage. of E m m A g ol dm A n’s Mot h er ea rt h “An indispensable book . a judicious, lively, and enlightening work.” —Paul Avrich, author of Anarchist Voices “Peter Glassgold has done a great service to the activist spirit by returning to print Mother Earth’s often stirring, always illuminating essays.” —Alix Kates Shulman, author of Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen “It is wonderful to have this collection of pieces from the days when anarchism was an ism— and so heady a brew that the government had to resort to illegal repression to squelch it. What’s more, it is still a heady brew.” —Kirkpatrick Sale, author of The Dwellers in the Land “Glassgold opens with an excellent brief history of the publication. -

The Rise of Ethical Anarchism in Britain, 1885-1900

1 e[/]pater 2 sie[\]cle THE RISE OF ETHICAL ANARCHISM IN BRITAIN 1885-1900 By Mark Bevir Department of Politics Newcastle University Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU U.K. ABSTRACT In the nineteenth century, anarchists were strict individualists favouring clandestine organisation and violent revolution: in the twentieth century, they have been romantic communalists favouring moral experiments and sexual liberation. This essay examines the growth of this ethical anarchism in Britain in the late nineteenth century, as exemplified by the Freedom Group and the Tolstoyans. These anarchists adopted the moral and even religious concerns of groups such as the Fellowship of the New Life. Their anarchist theory resembled the beliefs of counter-cultural groups such as the aesthetes more closely than it did earlier forms of anarchism. And this theory led them into the movements for sex reform and communal living. 1 THE RISE OF ETHICAL ANARCHISM IN BRITAIN 1885-1900 Art for art's sake had come to its logical conclusion in decadence . More recent devotees have adopted the expressive phase: art for life's sake. It is probable that the decadents meant much the same thing, but they saw life as intensive and individual, whereas the later view is universal in scope. It roams extensively over humanity, realising the collective soul. [Holbrook Jackson, The Eighteen Nineties (London: G. Richards, 1913), p. 196] To the Victorians, anarchism was an individualist doctrine found in clandestine organisations of violent revolutionaries. By the outbreak of the First World War, another very different type of anarchism was becoming equally well recognised. The new anarchists still opposed the very idea of the state, but they were communalists not individualists, and they sought to realise their ideal peacefully through personal example and moral education, not violently through acts of terror and a general uprising. -

The Universite of Oklahoma Graduate College M

THE UNIVERSITE OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE M ANALYSIS OF JOHN DOS PASSOS’ U.S.A. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHE BE F. UILLIAIl NELSON Norman, Oklahoma 1957 All ANALÏSIS OF JOHN DOS PASSOS' U.S.A. APPROVED 3Ï ijl^4 DISSERTATION COmTTEE TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. THE CRITICS....................................... 1 II. THE CAST .......................................... III. CLOSE-UP .......................................... ho IV. DOCUMENTARY ....................................... 63 V. MONTAGE........................................... 91 VI. CROSS-CUTTING ...................................... Il4 VII. SPECIAL EFFECTS .................................... 13o VIII. WIDE ANGLE LENS .................................... l66 IX. CRITIQUE .......................................... 185 APPENDK ................................................. 194 BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................. 245 111 ACKNOWLEDGEI'IENT Mjr thanks are due all those members of the Graduate Faculty of the Department of English who, knowingly and unknowingly, had a part in this work. My especial thanks to Professor Victor Elconin for his criticism and continued interest in this dissertation are long overdue. Alf ANALYSIS OF JOHN DOS PASSOS' U.S.A. CHAPTER I THE CRITICS The 42nd Parallel, the first volume of the trilogy, U.S.A., was first published on February 19, 1930- It was followed by 1919 on March 10, 1932, and The Big Money on August 1, 1936. U.S.A., which combines these three novels, was issued on January 27, 1938. There is as yet no full-length critical and biographical study of Dos Passes, although one is now in the process of being edited for publication.^ His work has, however, attracted the notice of the leading reviewers and is discussed in those treatises dealing with the American novel of the twentieth cen tury. -

From Squatting to Tactical Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2019 Between the Cracks: From Squatting to Tactical Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 Amanda S. Wasielewski The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3125 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BETWEEN THE CRACKS: FROM SQUATTING TO TACTICAL MEDIA ART IN THE NETHERLANDS, 1979–1993 by AMANDA WASIELEWSKI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partiaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 AMANDA WASIELEWSKI ALL Rights Reserved ii Between the Cracks: From Squatting to TacticaL Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 by Amanda WasieLewski This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy. Date David JoseLit Chair of Examining Committee Date RacheL Kousser Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Marta Gutman Lev Manovich Marga van MecheLen THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Between the Cracks: From Squatting to TacticaL Media Art in the Netherlands, 1979–1993 by Amanda WasieLewski Advisor: David JoseLit In the early 1980s, Amsterdam was a battLeground. During this time, conflicts between squatters, property owners, and the police frequentLy escaLated into fulL-scaLe riots.