Art and Spirituality in the Works of Sappho and Hildegard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 Video, “Chaucer’S England,” Chronicles the Development of Civilization in Medieval Europe

Toward a New World 800–1500 Key Events As you read, look for the key events in the history of medieval Europe and the Americas. • The revival of trade in Europe led to the growth of cities and towns. • The Catholic Church was an important part of European people’s lives during the Middle Ages. • The Mayan, Aztec, and Incan civilizations developed and administered complex societies. The Impact Today The events that occurred during this time period still impact our lives today. • The revival of trade brought with it a money economy and the emergence of capitalism, which is widespread in the world today. • Modern universities had their origins in medieval Europe. • The cultures of Central and South America reflect both Native American and Spanish influences. World History—Modern Times Video The Chapter 4 video, “Chaucer’s England,” chronicles the development of civilization in medieval Europe. Notre Dame Cathedral Paris, France 1163 Work begins on Notre Dame 800 875 950 1025 1100 1175 c. 800 900 1210 Mayan Toltec control Francis of Assisi civilization upper Yucatán founds the declines Peninsula Franciscan order 126 The cathedral at Chartres, about 50 miles (80 km) southwest of Paris, is but one of the many great Gothic cathedrals built in Europe during the Middle Ages. Montezuma Aztec turquoise mosaic serpent 1325 1453 1502 HISTORY Aztec build Hundred Montezuma Tenochtitlán on Years’ War rules Aztec Lake Texcoco ends Empire Chapter Overview Visit the Glencoe World History—Modern 1250 1325 1400 1475 1550 1625 Times Web site at wh.mt.glencoe.com and click on Chapter 4– Chapter Overview to 1347 1535 preview chapter information. -

God S Heroes

PUBLISHING GROUP:PRODUCT PREVIEW God’s Heroes A Child’s Book of Saints Children look up to and admire their heroes – from athletes to action figures, pop stars to princesses.Who better to admire than God’s heroes? This book introduces young children to 13 of the greatest heroes of our faith—the saints. Each life story highlights a particular virtue that saint possessed and relates the virtue to a child’s life today. God’s Heroes is arranged in an easy-to-follow format, with informa- tion about a saint’s life and work on the left and an fund activity on the right to reinforce the learning. Of the thirteen saints fea- tured, most will be familiar names for the children.A few may be new, which offers children the chance to get to know other great heroes, and maybe pick a new favorite! The 13 saints include: • St. Francis of Assisi 32 pages, 6” x 9” #3511 • St. Clare of Assisi • St. Joan of Arc • Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha • St. Philip Neri • St. Edward the Confessor In this Product Preview you’ll find these sample pages . • Table of Contents (page 1) • St. Francis of Assisi (pages 12-13) • Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha (pages 28-29) « Scroll down to view these pages. God’s Heroes A Child’s Book of Saints Featuring these heroes of faith and their timeless virtues. St. Mary, Mother of God . .4 St. Thomas . .6 St. Hildegard of Bingen . .8 St. Patrick . .10 St. Francis of Assisi . .12 St. Clare of Assisi . .14 St. Philip Neri . -

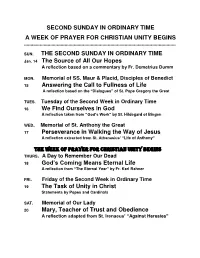

Second Sunday in Ordinary Time a Week of Prayer For

SECOND SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME A WEEK OF PRAYER FOR CHRISTIAN UNITY BEGINS …………………………………………………………………………………………………….. SUN. THE SECOND SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME Jan. 14 The Source of All Our Hopes A reflection based on a commentary by Fr. Demetrius Dumm MON. Memorial of SS. Maur & Placid, Disciples of Benedict 15 Answering the Call to Fullness of Life A reflection based on the “Dialogues” of St. Pope Gregory the Great TUES. Tuesday of the Second Week in Ordinary Time 16 We Find Ourselves in God A reflection taken from “God’s Work” by St. Hildegard of Bingen WED. Memorial of St. Anthony the Great 17 Perseverance in Walking the Way of Jesus A reflection extracted from St. Athanasius’ “Life of Anthony” The Week of Prayer for Christian Unity Begins THURS. A Day to Remember Our Dead 18 God’s Coming Means Eternal Life A reflection from “The Eternal Year” by Fr. Karl Rahner FRI. Friday of the Second Week in Ordinary Time 19 The Task of Unity in Christ Statements by Popes and Cardinals SAT. Memorial of Our Lady 20 Mary, Teacher of Trust and Obedience A reflection adapted from St. Irenaeus’ “Against Heresies” THE SOURCE OF ALL OUR HOPE A reflection adapted from a commentary by Fr. Demetrius Dumm In John’s version of the call of the first disciples, we read that Jesus had been pointed out to two of them by John; they then followed him, literally. “When he turned and saw them following him, he asked: What are you looking for? They said, Rabbi, where are you staying?” It would be a mistake to see this as simply an account of a friendly exchange between Jesus and the two disciples. -

Message of His Holiness Pope Francis to Participants in The

N. 201008a Thursday 08.10.2020 Message of His Holiness Pope Francis to participants in the webinar promoted by the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, “Women Read Pope Francis: reading, reflection and music” The following is the message sent by the Holy Father Francis to participants in the webinar promoted by the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, which took place yesterday, on the theme “Women Read Pope Francis: reading, reflection and music”: Message of the Holy Father Dear Friends, I offer a warm greeting to you, the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, on the occasion of the seminar “Women Read Pope Francis: Reading, Reflection and Music”, a series of meetings that now begins with the theme “Evangelii Gaudium”. Your gathering today highlights the novelty that you represent within the Roman Curia. For the first time, a Dicastery has involved a group of women by making them protagonists in developing cultural projects and approaches, and not simply to deal with women’s issues. Your Consultation Group is made up of women engaged in different sectors of the life of society and reflecting cultural and religious visions of the world that, however different, converge on the goal of working together in mutual respect. For your reading programme, you have chosen three of my writings: the Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, the Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’ and the Document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together. These works are devoted, respectively, to the themes of evangelization, creation and fraternity. -

Hildegard of Bingen Ginger L

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal of Women in Educational Leadership Educational Administration, Department of 10-2007 Women in History - Hildegard of Bingen Ginger L. Zierdt Minnesota State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel Zierdt, Ginger L., "Women in History - Hildegard of Bingen" (2007). Journal of Women in Educational Leadership. 60. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel/60 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Educational Administration, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Women in Educational Leadership by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Women in History Hildegard of Bingen Ginger L. Zierdt "Wisdom teaches in the light of love, and bids me tell how I was brought into this my gift of vision ..." (Hildegard) Visionary Prodigy Hildegard of Bingen was born in Bermersheim, Germany near Alzey in 1098 to the nobleman Hildebert von Bermersheim and his wife Mechthild, as their tenth and last child. Hildegard was brought by her parents to God as a "tithe" and determined for life in the Order. How ever, "rather than choosing to enter their daughter formally as a child in a convent where she would be brought up to become a nun (a practice known as 'oblation'), Hildegard's parents had taken the more radical step of enclosing their daughter, apparently for life, in the cell of an anchoress, Jutta, attached to the Benedictine monastery at Disibodenberg" (Flanagan, 1989, p. -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-64680-2 - The Cambridge Companion to Victorian Poetry Edited by Joseph Bristow Index More information INDEX Abdy, Maria 189 ``Isolation: To Marguerite'' 209 Adams, James Eli Merope 118, 120, 218 Dandies and Desert Saints 203 ``Preface'' 118±19, 218 Aeschylus 120 ``Resignation: To Fausta'' 19±20 aesthetics, Romantic 51±4 ``The Scholar-Gipsy'' 53±6, 65, 224 aestheticism 228±52, 290, 292±3, 300 ``Stanzas from the Grande Chartreuse'' 128 Aguilar, Grace 166±70, 177, 191 ``The Study of Poetry'' 52±3, 164, 228, ``Song of the Spanish Jews'' 166, 167±70 229 Alaya, Flavia 262 ``Switzerland'' 209, 223 Albert, Prince 131, 285 ``To Marguerite ± Continued'' 209±10 Alden, Raymond Macdonald ``Tristram and Iseult'' 210±12, 223±4 Alfred Tennyson 29 astronomy 140, 149, 153 Altick, Richard D. 165 Athenaeum 5 Anaximenes 151 Attridge, Derek 100 Anderson, Benedict 256 Austin, Alfred 214, 283, 286, 287±8 Anglican Church 132, 160±2, 163±4, 165, England's Darling 298 170, 173 authority, cultural 203 annuals 190±2 Apostles Society, Cambridge University 8, 33, Bacon, Francis 137 36, 139 Bakhtin, Mikhail 59, 66 Arata, Stephen D. 272 Baudelaire, Charles Aristotle 141, 142, 218 Les ¯eurs du mal 21 Ethics 244 Notes nouvelles sur Edgar Poe 21 Armstrong, Isobel 199 Beardsley, Aubrey 287, 295 Victorian Poetry 32±3, 56±7, 86, 130, Beddoes, Thomas Lovell xix 180 Beer, Gillian 133, 153 Armstrong, Nancy 39, 203 Bentham, Jeremy 5±6 Arnold, Sir Edwin 288 Bhagavad-Gita 20 The Light of Asia 287±8 Bible 150±1, 160, 170 Arnold, Matthewxviii, xx, -

Channeling Hildegard of Bingen: Transcending Time and Fanning the Flame Helen C

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal of Women in Educational Leadership Educational Administration, Department of 2007 Channeling Hildegard of Bingen: Transcending Time and Fanning the Flame Helen C. Sobehart Duquesne University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel Sobehart, Helen C., "Channeling Hildegard of Bingen: Transcending Time and Fanning the Flame" (2007). Journal of Women in Educational Leadership. 10. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Educational Administration, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Women in Educational Leadership by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Channeling Hildegard of Bingen: Transcending Time and Fanning the Flame Helen C. Sobehart "You know, Hildegard, I didn't ask for this calling to support the cause of women." "Well I didn't ask for what happened to me either, Helen. Ijust happened to be born the tenth child of a wealthy family in the twelfth century. Do you know where the word "tithe" comes from? In my day, the 'tenth' child was 'donated'to the church. So stop whining and let's get on with this story." "Kind of cheeky for a 12th century nun, aren't you?" "We mystics can take on the vernacular of the time-should that be so surpris ing? In fact, one of my biographers correctly observed that there were 'limits to my patience and humility, and that 'meek' and 'ordinary' were the last words to describe me" (Flanagan, 1998, p. -

Creation Care Season September 30 – November 30 Creation Care

Creation Care Season Creation Care Season September 30 – November 30 September 30 – November 30 Diocesan Convention 2010 voted to encourage every Diocesan Convention 2010 voted to encourage every congregation to observe and celebrate a season of thanksgiving congregation to observe and celebrate a season of thanksgiving and wonder for the life-giving seasons of God’s creation. and wonder for the life-giving seasons of God’s creation. Clean air and clear water are threatened by human neglect, Clean air and clear water are threatened by human neglect, natural resource consumption, and pollution caused by burning natural resource consumption, and pollution caused by burning fossil fuels. fossil fuels. The health of the Earth affects us all, but especially vulnerable The health of the Earth affects us all, but especially vulnerable poor, sick, and young people. poor, sick, and young people. Creation Care Season calls us to act on behalf of our Creating Creation Care Season calls us to act on behalf of our Creating God, the Earth, our children, and other people by adopting God, the Earth, our children, and other people by adopting creation care holy habits such as: creation care holy habits such as: • Designate a Sunday between Sept. 30—Nov. 30 as Creation • Designate a Sunday between Sept. 30—Nov. 30 as Creation Care Sunday, asking people to give generously to support a Care Sunday, asking people to give generously to support a Creation Care project in the parish, community, or Diocese. Creation Care project in the parish, community, or Diocese. • Explore ways your household can save energy and reduce its • Explore ways your household can save energy and reduce its carbon footprint. -

The Greatest Faith Ever Preached Sunday December 30, 2012 We've

The Greatest Faith Ever Preached Sunday December 30, 2012 We’ve had a great year as a church in 2012. God has been very gracious to us. We’ve seen wonderful growth in reaching out to people • GodTV • We were part of VisionIndia training up 8,600 young people from about 15 states across North India. In addition, 12,000 sets of our Hindi publications (12 titles) i.e. 1,44,000 copies of our publications distributed at VisionIndia itself! • Short Term Bible college at Champa, where we graduated 45 students • Missions Trips by our young people to Chattarpur • Two more new locations in Bangalore East and West • APC-Mangalore moved into Mangalore city and encouraging response from students there • APC moved into a new office • …and so much more… As we look ahead to 2013, we as a church must be ready to reach out both in our city and across our nation. Jesus gave one of the indicators of the end of this age. He said “And this gospel of the kingdom will be preached in all the world as a witness to all the nations, and then the end will come.” (Matthew 24:14) This morning we are going to talk about “The Greatest Faith Ever Preached” Mark 16:14-20 There were 11 unbelieving disciples. Jesus rebuked them for their unbelief and hardness of heart – even after being with Jesus for 3 years, seeing and hearing all that He did and taught – they still doubted His resurrection. To these men, He gave the great commission – to take the Gospel to the ends of the world! From a group of 11 unbelieving disciples, the Gospel of Jesus Christ, has spread to the nations. -

The Rhineland Mystics

Mendicantthe The Rhineland Mystics This year in Daily Meditations I’m exploring my “Wisdom 1328), Johannes Tauler (1300-1361), and Henry Suso Lineage,” the teachers, texts, and traditions that have most (c.1300-1366); and Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa (1401- influenced my spirituality and teaching. (Read my introduction 1464), the teacher of “dialectical mysticism” and “learned to the Wisdom Lineage in the January 2015 issue of The ignorance.” In more recent history, another Rhineland Mendicant and “Desert Christianity and the Eastern Fathers Mystic who might surprise (or shock) some of you was Carl of the Church” in the April 2015 issue at cac.org/about-cac/ Gustave Jung (1875-1961), who lived much of his life on newsletter.) —Richard Rohr, OFM the southern end of the Rhine in both Basel and Zurich, Switzerland. He himself admits he term Rhineland to being influenced by Hildegard, Mystics refers to the Eckhart, and Nicholas of Cusa’s mostly German-speaking fascination with “the opposites.” spiritual writers, preach- The mystical path was largely Ters, and teachers, who lived largely mistrusted and, some would say, between the 11th and 15th cen- squelched after Martin Luther’s turies, and whose importance has strongly stated prejudice against only recently been rediscovered. “mysticism,” emphasizing Scripture The “Trans-Alpine” Church always to such a degree that personal enjoyed a certain degree of freedom spiritual experience was considered from Roman oversight and control, unimportant and almost always simply by reason of distance, and of Bingen, 1165. Hildegard by suspect. Of course he had seen its drew upon different sources and misuse and manipulation in the Scivias inspirations than did the “Cis- medieval Catholic world, where Alpine” Church of Italy, France, and pre-rational thinking was com- Spain. -

MYSTICISM Christina Van Dyke

P1: SJT Trim: 6in 9in Top: 0.625in Gutter: 0.875in × CUUK851-52 CUUK618/Pasnau ISBN: 978 0 521 86672 9 May 20, 2009 20:18 52 MYSTICISM christina van dyke Current scholars generally behave as though the medieval traditions of mysticism and philosophy in the Latin West have nothing to do with each other; in large part, this appears to be the result of the common perception that mysticism has as its ultimate goal an ecstatic, selfless union with the divine that intellectual pursuits such as philosophy inhibit rather than support. There are, however, at least two central problems with this assumption. First, mysticism in the Middle Ages – even just within the Christian tradition1 – was not a uniform movement with a single goal: it took different forms in different parts of Europe, and those forms changed substantially from the eleventh to the fifteenth century, particularly with the increased emphasis on personal piety and the feminization of religious imagery that emerges in the later centuries.2 The belief that mysticism entails the rejection or abandonment of reason in order to merge with the divine, for instance, represents only one strain of the medieval tradition. Although this view is explicitly advocated in the Christian West by such influential figures as Meister Eckhart and Marguerite Porete, the prevalent identification of the allegorical figure of Wisdom with Christ provides the grounds for equally prominent figures such as Hildegard of 1 In several respects, mysticism played a more integral role in Arabic and Jewish philosophy than in Christian philosophy from late antiquity through the Middle Ages. -

The Spiritual Value of Singing the Liturgy for Hildegard of Bingen

THAT THEY MIGHT SING THE SONG OF THE LAMB: THE SPIRITUAL VALUE OF SINGING THE LITURGY FOR HILDEGARD OF BINGEN. A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Science TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada (c) Copyright by Miranda Lynn Clemens (Sister Maria Parousia) 2014 History M.A. Graduate Program September 2014 Abstract That They Might Sing the Song of the Lamb: The Spiritual Value of Singing the Liturgy for Hildegard of Bingen. Miranda Lynn Clemens (Sister Maria Parousia) This thesis examines Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179)'s theology of music, using as a starting place her letter to the Prelates of Mainz, which responds to an interdict prohibiting Hildegard's monastery from singing the liturgy. Using the twelfth-century context of female monasticism, liturgy, music theory and ideas about body and soul, the thesis argues that Hildegard considered the sung liturgy essential to monastic formation. Music provided instruction not only by informing the intellect but also by moving the affections to embrace a spiritual good. The experience of beauty as an educational tool reflected the doctrine of the Incarnation. Liturgical music helped nuns because it reminded them their final goal was heaven, helped them overcome sin and facilitated participation in the angelic choirs. Ultimately losing the ability to sing the liturgy was not a minor inconvenience, but the loss of a significant spiritual and educational tool fundamental to achieving union with God. Key words: Hildegard of Bingen, Letter to the Prelates of Mainz, monasticism, liturgy, music medieval music theory, medieval aesthetics, body and soul, education.