The Case of the Hula Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf, 366.38 Kb

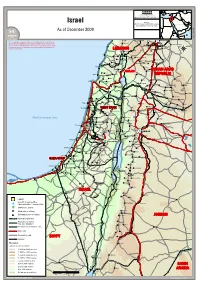

FF II CC SS SS Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services Israel Sources: UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. As of December 2009 Israel_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Dahr al Ahmar Jarba The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the 'Aramtah Ma'adamiet Shih Harran al 'Awamid Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, Qatana Haouch Blass 'Artuz territory, city or area of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its Najha frontiers or boundaries LEBANON Al Kiswah Che'baâ Douaïr Al Khiyam Metulla Sa`sa` ((( Kafr Dunin Misgav 'Am Jubbata al Khashab ((( Qiryat Shemons Chakra Khan ar Rinbah Ghabaqhib Rshaf Timarus Bent Jbail((( Al Qunaytirah Djébab Nahariyya El Harra ((( Dalton An Namir SYRIAN ARAB Jacem Hatzor GOLANGOLAN Abu-Senan GOLANGOLAN Ar Rama Acre ((( Boutaiha REPUBLIC Bi'nah Sahrin Tamra Shahba Tasil Ash Shaykh Miskin ((( Kefar Hittim Bet Haifa ((( ((( ((( Qiryat Motzkin ((( ((( Ibta' Lavi Ash Shajarah Dâail Kafr Kanna As Suwayda Ramah Kafar Kama Husifa Ath Tha'lah((( ((( ((( Masada Al Yadudah Oumm Oualad ((( ((( Saïda 'Afula ((( ((( Dar'a Al Harisah ((( El 'Azziya Irbid ((( Al Qrayyah Pardes Hanna Besan Salkhad ((( ((( ((( Ya'bad ((( Janin Hadera ((( Dibbin Gharbiya El-Ne'aime Tisiyah Imtan Hogla Al Manshiyah ((( ((( Kefar Monash El Aânata Netanya ((( WESTWEST BANKBANK WESTWEST BANKBANKTubas 'Anjara Khirbat ash Shawahid Al Qar'a' -

ISRAEL 15 Study Visit What Will It Take to Leap Israel's Social and Economic Performance? Mon-Thu, June 8 – June 11, 2009

1 March 2009 ISRAEL 15 Study Visit What Will It Take to Leap Israel's Social and Economic Performance? Mon-Thu, June 8 – June 11, 2009 The ISRAEL 15 Vision The ISRAEL 15 Vision aims to place Israel among the fifteen leading countries in terms of quality of life. This vision requires a 'leapfrog' from our present state of development i.e. a significant and continuous improvement in Israel's social and economic performance in comparison to other countries. Our Study Visit will focus on this vision and challenge. The ISRAEL 15 Agenda and Strategy There is no recipe for leapfrogging; it is the result of a virtuous alignment in economic policy, powerful global trends and national leadership. Few countries have leapt including Ireland, Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Chile, and Israel (between the 50s- 70s). The common denominator among these countries has been their agenda. They focused on: developing a rich and textured vision; exhausting engines of growth; tapping into unique advantages; improving the capacity for taking decisions and implementing them; benchmarking with other countries; and turning development and growth into a national obsession. Furthermore, leapfrogging requires a top-down process driven by the government, as well as a bottom-up mobilization of the key sectors of society such as mayors and municipal governments, business leaders, nonprofits, philanthropists, career public servants and, in Israel's case, also the world Jewry. The Study Visit will explore this agenda as it applies to Israel. The Second ISRAEL 15 Conference; Monday, June 8, 2009 The Second ISRAEL 15 Conference titled: "Effectuating the Vision Now!" will be held on Monday, June 8th. -

Introduction Really, 'Human Dust'?

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Peck, The Lost Heritage of the Holocaust Survivors, Gesher, 106 (1982) p.107. 2. For 'Herut's' place in this matter, see H. T. Yablonka, 'The Commander of the Yizkor Order, Herut, Shoa and Survivors', in I. Troen and N. Lucas (eds.) Israel the First Decade, New York: SUNY Press, 1995. 3. Heller, On Struggling for Nationhood, p. 66. 4. Z. Mankowitz, Zionism and the Holocaust Survivors; Y. Gutman and A. Drechsler (eds.) She'erit Haplita, 1944-1948. Proceedings of the Sixth Yad Vas hem International Historical Conference, Jerusalem 1991, pp. 189-90. 5. Proudfoot, 'European Refugees', pp. 238-9, 339-41; Grossman, The Exiles, pp. 10-11. 6. Gutman, Jews in Poland, pp. 65-103. 7. Dinnerstein, America and the Survivors, pp. 39-71. 8. Slutsky, Annals of the Haganah, B, p. 1114. 9. Heller The Struggle for the Jewish State, pp. 82-5. 10. Bauer, Survivors; Tsemerion, Holocaust Survivors Press. 11. Mankowitz, op. cit., p. 190. REALLY, 'HUMAN DUST'? 1. Many of the sources posed problems concerning numerical data on immi gration, especially for the months leading up to the end of the British Mandate, January-April 1948, and the first few months of the state, May August 1948. The researchers point out that 7,574 immigrant data cards are missing from the records and believe this to be due to the 'circumstances of the times'. Records are complete from September 1948 onward, and an important population census was held in November 1948. A parallel record ing system conducted by the Jewish Agency, which continued to operate after that of the Mandatory Government, provided us with statistical data for immigration during 1948-9 and made it possible to analyse the part taken by the Holocaust survivors. -

Jnf Blueprint Negev: 2009 Campaign Update

JNF BLUEPRINT NEGEV: 2009 CAMPAIGN UPDATE In the few years since its launch, great strides have been made in JNF’s Blueprint Negev campaign, an initiative to develop the Negev Desert in a sustainable manner and make it home to the next generation of Israel’s residents. In Be’er Sheva: More than $30 million has already been invested in a city that dates back to the time of Abraham. For years Be’er Sheva was an economically depressed and forgotten city. Enough of a difference has been made to date that private developers have taken notice and begun to invest their own money. New apartment buildings have risen, with terraces facing the riverbed that in the past would have looked away. A slew of single family homes have sprung up, and more are planned. Attracted by the River Walk, the biggest mall in Israel and the first “green” one in the country is Be’er Sheva River Park being built by The Lahav Group, a private enterprise, and will contribute to the city’s communal life and all segments of the population. The old Turkish city is undergoing a renaissance, with gaslights flanking the refurbished cobblestone streets and new restaurants, galleries and stores opening. This year, the municipality of Be’er Sheva is investing millions of dollars to renovate the Old City streets and support weekly cultural events and activities. And the Israeli government just announced nearly $40 million to the River Park over the next seven years. Serious headway has been made on the 1,700-acre Be’er Sheva River Park, a central park and waterfront district that is already transforming the city. -

A Test of Rival Strategies: Two Ships Passing in the Night

Chapter 4 A Test of Rival Strategies: Two Ships Passing in the Night Giora Romm The purpose of this essay is to analyze several prominent military aspects of the war in Lebanon and derive the main lessons from them. The essay does not deal in historical explanations of what caused any particular instance of military thinking or any specific achievement. Rather, the analysis points to four main conclusions: the importance of clear expression at the command level to reduce the battle fog; the phenomenon of military blindness with respect to the role played by short range rockets (Katyushas) in the overall military campaign; the alarming performance of the ground forces; and the critical importance of an exit strategy and identification of the war’s optimal end point from the very outset of the war. The War and its Goals The 2006 Lebanon war began on July 12 and continued for thirty-three days. The event began as a military operation designed to last one day or a few days. As matters dragged on and became more complicated, more vigorous terms were used to describe the fighting. Several months after the campaign, the government officially recognized it as a “war.” This was a war in which the political leadership tried to define political goals before the war and in the opening days of the fighting, something that did not occur in most of Israel’s wars. This attempt was unsuccessful, however. What appeared to be the political goals changed in the course 50 I Giora Romm of the fighting, at least judging by speeches made by the senior political leadership during the conflict. -

Field Trip 2017 Israel

YEP Field Trip 2017 Israel Technology Tour Itinerary YEP – Young Engineers’ Panel 5.11.2017 DAY 1 • Pickup (08:30 AM): Eilat airport and north beach hotel. • Ramon Crater: The world’s largest erosion crater (makhtesh). A landform unique to Israel, Egypt and Sinai desert, it is a large erosion cirque, created 220 million years ago when oceans covered the area. The Ramon Crater measures 40 km in length and between 2 and 10km in width, shaped like a long heart, and forms Israel’s largest national park, the Ramon Nature Reserve. • Ramon Visitors Center, located on the edge of Makhtesh Ramon is overlooking the Crater. It displays the geography, geology, flora, fauna and history of the region from prehistoric to modern times. A film explains how the Makhtesh was formed and a three-dimensional interactive model helps bring home an understanding of the topography of this unique region. • Sde Boker kibbutz is famous as the home of David Ben Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister whose home is now a museum open to the public, and is the feature of a number of supporting exhibits in the kibbutz. Sde Boker is a community founded in 1952 by a number of pioneering families who were later joined by Ben Gurion after an interesting encounter. South of Sde Boker is Ben Gurion’s burial site, which is set in an incredible location overlooking one of the most striking and impressive views in the Negev, across the Zin Valley. 1 • Ashalim (Technology tour) - Solar Energy (thermal and PV) Solar power tower and Solar field. -

A Guide to Birding in Israel & Trip Report for 25 April – 5 May 2019

A Guide to Birding in Israel & Trip Report for 25th April – 5th May 2019 Trip Report author: Steve Arlow [email protected] Blog for further images: https://stevearlowsbirding.blogspot.com/ Purpose of this Trip Report / Guide I have visited Israel numerous times since spring since 2012 and have produced birding trip reports for each of those visits however for this report I have collated all of my previous useful information and detail, regardless if they were visited this year or not. Those sites not visited this time around are indicated within the following text. However, if you want to see the individual trip reports the below are detailed in Cloudbirders. March 2012 March 2013 April – May 2014 March 2016 April – May 2016 March 2017 April – May 2018 Summary of the Trip This year’s trip in late April into early May was not my first choice for dates, not even my second but it delivered on two key target species. Originally I had wanted to visit from mid-April to catch the Levant Sparrowhawk migration that I have missed so many previous times before however this coincided with Passover holidays in Israel and accommodation was either not available (Lotan) or bonkersly expensive (Eilat) plus the car rental prices were through the roof and there would be holiday makers everywhere. I decided then to return in March and planned to take in the Hula (for the Crane spectacle), Mt. Hermon, the Golan, the Beit She’an Valley, the Dead Sea, Arava and Negev as an all-rounder. However I had to cancel the day I was due to travel as an issue arose at home that I just had to be there for. -

6-194E.Pdf(6493KB)

Samuel Neaman Eretz Israel from Inside and Out Samuel Neaman Reflections In this book, the author Samuel (Sam) Neaman illustrates a part of his life story that lasted over more that three decades during the 20th century - in Eretz Israel, France, Syria, in WWII battlefronts, in Great Britain,the U.S., Canada, Mexico and in South American states. This is a life story told by the person himself and is being read with bated breath, sometimes hard to believe but nevertheless utterly true. Neaman was born in 1913, but most of his life he spent outside the country and the state he was born in ERETZ and for which he fought and which he served faithfully for many years. Therefore, his point of view is from both outside and inside and apart from • the love he expresses towards the country, he also criticizes what is going ERETZ ISRAELFROMINSIDEANDOUT here. In Israel the author is well known for the reknowned Samuel Neaman ISRAEL Institute for Advanced Studies in Science and Technology which is located at the Technion in Haifa. This institute was established by Neaman and he was directly and personally involved in all its management until he passed away a few years ago. Samuel Neaman did much for Israel’s security and FROM as a token of appreciation, all IDF’s chiefs of staff have signed a a megila. Among the signers of the megila there were: Ig’al Yadin, Mordechai Mak- lef, Moshe Dayan, Haim Laskov, Zvi Zur, Izhak Rabin, Haim Bar-Lev, David INSIDE El’arar, and Mordechai Gur. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2005 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service ► The o rganization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state re porting requirements. A For the 2005 calendar year , or tax year be and B Check If C Name of organization D Employer Identification number applicable Please use IRS change ta Qachange RICA IS RAEL CULTURAL FOUNDATION 13-1664048 E; a11gne ^ci See Number and street (or P 0. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 0jretum specific 1 EAST 42ND STREET 1400 212-557-1600 Instruo retum uons City or town , state or country, and ZIP + 4 F nocounwro memos 0 Cash [X ,camel ded On° EW YORK , NY 10017 (sped ► [l^PP°ca"on pending • Section 501 (Il)c 3 organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trusts H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations. must attach a completed Schedule A ( Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates ? Yes OX No G Website : : / /AICF . WEBNET . ORG/ H(b) If 'Yes ,* enter number of affiliates' N/A J Organization type (deckonIyone) ► [ 501(c) ( 3 ) I (insert no ) ] 4947(a)(1) or L] 527 H(c) Are all affiliates included ? N/A Yes E__1 No Is(ITthis , attach a list) K Check here Q the organization' s gross receipts are normally not The 110- if more than $25 ,000 . -

My Life's Story

My Life’s Story By Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz 1915-2000 Biography of Lieutenant Colonel Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz Z”L , the son of Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Shwartz Z”L , and Rivka Shwartz, née Klein Z”L Gilad Jacob Joseph Gevaryahu Editor and Footnote Author David H. Wiener Editor, English Edition 2005 Merion Station, Pennsylvania This book was published by the Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz Memorial Committee. Copyright © 2005 Yona Shwartz & Gilad J. Gevaryahu Printed in Jerusalem Alon Printing 02-5388938 Editor’s Introduction Every Shabbat morning, upon entering Lower Merion Synagogue, an Orthodox congregation on the outskirts of the city of Philadelphia, I began by exchanging greetings with the late Lt. Colonel Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz. He used to give me news clippings and booklets which, in his opinion, would enhance my knowledge. I, in turn, would express my personal views on current events, especially related to our shared birthplace, Jerusalem. Throughout the years we had an unwritten agreement; Eliyahu would have someone at the Israeli Consulate of Philadelphia fax the latest news in Hebrew to my office (Eliyahu had no fax machine at the time), and I would deliver the weekly accumulation of faxes to his house on Friday afternoons before Shabbat. This arrangement lasted for years. Eliyahu read the news, and distributed the material he thought was important to other Israelis and especially to our mutual friend Dr. Michael Toaff. We all had an inherent need to know exactly what was happening in Israel. Often, during my frequent visits to Israel, I found that I was more current on happenings in Israel than the local Israelis. -

Daughters of the Vale of Tears

TUULA-HANNELE IKONEN Daughters of the Vale of Tears Ethnographic Approach with Socio-Historical and Religious Emphasis to Family Welfare in the Messianic Jewish Movement in Ukraine 2000 ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the board of the School of Social Sciences and Humanities of the University of Tampere, for public discussion in the Väinö Linna-Auditorium K104, Kalevantie 5, Tampere, on February 27th, 2013, at 12 o’clock. UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE ACADEMIC DISSERTATION University of Tampere School of Social Sciences and Humanities Finland Copyright ©2013 Tampere University Press and the author Distribution Tel. +358 40 190 9800 Bookshop TAJU [email protected] P.O. Box 617 www.uta.fi/taju 33014 University of Tampere http://granum.uta.fi Finland Cover design by Mikko Reinikka Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1809 Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 1285 ISBN 978-951-44-9059-0 (print) ISBN 978-951-44-9060-6 (pdf) ISSN-L 1455-1616 ISSN 1456-954X ISSN 1455-1616 http://acta.uta.fi Tampereen Yliopistopaino Oy – Juvenes Print Tampere 2013 Abstract This ethnographic approach with socio•historical and religious emphasis focuses on the Mission view of Messianic Jewish women in Ukraine circa 2000. The approach highlights especially the meaning of socio•historical and religious factors in the emergence of the Mission view of Messianic Jewish women. Ukraine, the location of this study case, is an ex•Soviet country of about 48 million citizens with 100 ethnic nationalities. Members of the Jewish Faith form one of those ethnic groups. Following the Russian revolution in 1989 and then the establishing of an independent Ukraine in 1991, the country descended into economic disaster with many consequent social problems. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District.