Rural Populations Faced with Environmental Hazards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B E N I N Benin

Birnin o Kebbi !( !( Kardi KANTCHARIKantchari !( !( Pékinga Niger Jega !( Diapaga FADA N'GOUMA o !( (! Fada Ngourma Gaya !( o TENKODOGO !( Guéné !( Madécali Tenkodogo !( Burkina Faso Tou l ou a (! Kende !( Founogo !( Alibori Gogue Kpara !( Bahindi !( TUGA Suroko o AIRSTRIP !( !( !( Yaobérégou Banikoara KANDI o o Koabagou !( PORGA !( Firou Boukoubrou !(Séozanbiani Batia !( !( Loaka !( Nansougou !( !( Simpassou !( Kankohoum-Dassari Tian Wassaka !( Kérou Hirou !( !( Nassoukou Diadia (! Tel e !( !( Tankonga Bin Kébérou !( Yauri Atakora !( Kpan Tanguiéta !( !( Daro-Tempobré Dammbouti !( !( !( Koyadi Guilmaro !( Gambaga Outianhou !( !( !( Borogou !( Tounkountouna Cabare Kountouri Datori !( !( Sécougourou Manta !( !( NATITINGOU o !( BEMBEREKE !( !( Kouandé o Sagbiabou Natitingou Kotoponga !(Makrou Gurai !( Bérasson !( !( Boukombé Niaro Naboulgou !( !( !( Nasso !( !( Kounounko Gbangbanrou !( Baré Borgou !( Nikki Wawa Nambiri Biro !( !( !( !( o !( !( Daroukparou KAINJI Copargo Péréré !( Chin NIAMTOUGOU(!o !( DJOUGOUo Djougou Benin !( Guerin-Kouka !( Babiré !( Afekaul Miassi !( !( !( !( Kounakouro Sheshe !( !( !( Partago Alafiarou Lama-Kara Sece Demon !( !( o Yendi (! Dabogou !( PARAKOU YENDI o !( Donga Aledjo-Koura !( Salamanga Yérémarou Bassari !( !( Jebba Tindou Kishi !( !( !( Sokodé Bassila !( Igbéré Ghana (! !( Tchaourou !( !(Olougbé Shaki Togo !( Nigeria !( !( Dadjo Kilibo Ilorin Ouessé Kalande !( !( !( Diagbalo Banté !( ILORIN (!o !( Kaboua Ajasse Akalanpa !( !( !( Ogbomosho Collines !( Offa !( SAVE Savé !( Koutago o !( Okio Ila Doumé !( -

The Gold Standard Micro-Programme Activity Design Document Template (Vpa-Dd)

TITLE OF THE MICRO-PROGRAMME: GS2489 Efficient cookstoves in Benin and Togo ANNEX AO – THE GOLD STANDARD MICRO-PROGRAMME ACTIVITY DESIGN DOCUMENT TEMPLATE (VPA-DD) CONTENTS A. General description of micro-programme activity (VPA) B. Eligibility of VPA and Estimation of Emission Reductions C. Stakeholder comments Annexes Annex 1: Contact information on entity/individual responsible for the VPA Annex 2: Information regarding public funding This template shall not be altered. It shall be completed without modifying/adding headings or logo, format or font. 1 TITLE OF THE MICRO-PROGRAMME: GS2489 Efficient cookstoves in Benin and Togo SECTION A. General description of micro-programme activity (VPA) A.1. Title of the micro-scale VPA: Title: GS2489 Efficient cookstoves in Benin and Togo – VPA2 – EcoBenin – Wanrou efficient cookstoves in Atacora/Donga region GS nr: GS6008 Date: 28/08/2017 Version: 01 A.2. Description of the micro-scale VPA: >> The departments of Atacora / Donga, are suffering from severe deforestation due to the rapid increase of its population and their energy needs. 91% of the households in the Atacora/Donga departments use fuelwood as main combustion fuel.1 According to the document SCRP -Benin 2011- 20152, 69% of the population of this region is considered as poor. In this region, the cooking of meals is done on traditional three stones coosktoves, which have a very low energy efficiency. The new project "Promotion of the Wanrou efficient cookstove in the region of Atacora/Donga (ProWAD)”3 4 is included as VPA-2 in the program of activities (PoA) GS2489 "Efficient cookstoves in Benin and Togo" and is implemented by EcoBenin. -

Carte Pédologique De Reconnaissance De La République Populaire Du Bénin À 1/200.000 : Feuille De Djougou

P. FAURE NOTICE EXPLICATIVE No 66 (4) CARTE PEDOLOGIQUE DE RECONNAISSANCE de la République Populaire du Bénin à 1/200.000 Feuille de DJOUGOU OFFICE OE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIWE ET TECHNIOUE OUTRE-MER 1 PARIS 1977 NOTICE EXPLICATIVE No 66 (4) CARTE PEDOLOGIQUE DE RECONNAISSANCE de la RepubliquePopulaire du Bénin à 1 /200.000 Feuille de DJOUGOU P. FAURE ORSTOM PARIS 1977 @ORSTOM 2977 ISBN 2-7099-0423-3(édition cornpl8te) ISBN 2-7099-0433-0 SOMMAI RE l. l INTRODUCTION ........................................ 1 I .GENERALITES SUR LE MILIEU ET LA PEDOGENESE ........... 3 Localisationgéographique ............................ 3 Les conditionsde milieu 1. Le climat ................... 3 2 . La végétation ................. 6 3 . Le modelé et l'hydrographie ....... 8 4 . Le substratum géologique ........ 10 Les matériaux originels et la pédogenèse .................. 12 1 . Les matériaux originels .......... 12 2 . Les processus pédogénétiques ...... 13 II-LESSOLS .......................................... 17 Classification 1. Principes de classification ....... 17 2 . La légende .................. 18 Etudemonographique 1 . Les sols minérauxbruts ......... 20 2 . Les sois peuévolués ............ 21 3 . Les sols ferrugineuxtropicaux ....... 21 4 . Les sols ferraliitiques ........... 38 CONCLUSION .......................................... 43 Répartitiondes' sols . Importance relative . Critèresd'utilisation . 43 Les principalescontraintes pour la mise en valeur ............ 46 BIBLIOGRAPHIE ........................................ 49 1 INTRODUCTION La carte pédologique de reconnaissance à 1/200 000, feuille DJOUGOU, fait partie d'un ensemble de neuf coupures imprimées couvrant la totalité du terri- toire de la République Populaire du Bénin. Les travaux de terrain de la couverture générale ont été effectués de 1967 à 1971 par les quatre pédologues de la Section de Pédologie du Centre O. R.S. T.O.M. de Cotonou : D. DUBROEUCQ, P. FAURE, M. VIENNOT, B. -

Comparative Analysis of Diversity and Utilization of Edible Plants in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas in Benin Alcade C Segnon* and Enoch G Achigan-Dako

Segnon and Achigan-Dako Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2014, 10:80 http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/10/1/80 JOURNAL OF ETHNOBIOLOGY AND ETHNOMEDICINE RESEARCH Open Access Comparative analysis of diversity and utilization of edible plants in arid and semi-arid areas in Benin Alcade C Segnon* and Enoch G Achigan-Dako Abstract Background: Agrobiodiversity is said to contribute to the sustainability of agricultural systems and food security. However, how this is achieved especially in smallholder farming systems in arid and semi-arid areas is rarely documented. In this study, we explored two contrasting regions in Benin to investigate how agroecological and socioeconomic contexts shape the diversity and utilization of edible plants in these regions. Methods: Data were collected through focus group discussions in 12 villages with four in Bassila (semi-arid Sudano-Guinean region) and eight in Boukoumbé (arid Sudanian region). Semi-structured interviews were carried out with 180 farmers (90 in each region). Species richness and Shannon-Wiener diversity index were estimated based on presence-absence data obtained from the focus group discussions using species accumulation curves. Results: Our results indicated that 115 species belonging to 48 families and 92 genera were used to address food security. Overall, wild species represent 61% of edible plants collected (60% in the semi-arid area and 54% in the arid area). About 25% of wild edible plants were under domestication. Edible species richness and diversity in the semi-arid area were significantly higher than in the arid area. However, farmers in the arid area have developed advanced resource-conserving practices compared to their counterparts in the semi-arid area where slash-and-burn cultivation is still ongoing, resulting in natural resources degradation and loss of biodiversity. -

The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte D'ivoire, and Togo

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Public Disclosure Authorized Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon Public Disclosure Authorized 00000_CVR_English.indd 1 12/6/17 2:29 PM November 2017 The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 1 11/29/17 3:34 PM Photo Credits Cover page (top): © Georges Tadonki Cover page (center): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Cover page (bottom): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Page 1: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 7: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 15: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 32: © Dominic Chavez/World Bank Page 48: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 56: © Ami Vitale/World Bank 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 2 12/6/17 3:27 PM Acknowledgments This study was prepared by Nga Thi Viet Nguyen The team greatly benefited from the valuable and Felipe F. Dizon. Additional contributions were support and feedback of Félicien Accrombessy, made by Brian Blankespoor, Michael Norton, and Prosper R. Backiny-Yetna, Roy Katayama, Rose Irvin Rojas. Marina Tolchinsky provided valuable Mungai, and Kané Youssouf. The team also thanks research assistance. Administrative support by Erick Herman Abiassi, Kathleen Beegle, Benjamin Siele Shifferaw Ketema is gratefully acknowledged. Billard, Luc Christiaensen, Quy-Toan Do, Kristen Himelein, Johannes Hoogeveen, Aparajita Goyal, Overall guidance for this report was received from Jacques Morisset, Elisée Ouedraogo, and Ashesh Andrew L. Dabalen. Prasann for their discussion and comments. Joanne Gaskell, Ayah Mahgoub, and Aly Sanoh pro- vided detailed and careful peer review comments. -

Congressional Budget Justification 2015

U.S. AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION Pathways to Prosperity “Making Africa’s Growth Story Real in Grassroots Communities” CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET JUSTIFICATION Fiscal Year 2015 March 31, 2014 Washington, D.C. United States African Development Foundation (This page was intentionally left blank) 2 USADF 2015 CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET JUSTIFICATION United States African Development Foundation THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION WASHINGTON, DC We are pleased to present to the Congress the Administration’s FY 2015 budget justification for the United States African Development Foundation (USADF). The FY 2015 request of $24 million will provide resources to establish new grants in 15 African countries and to support an active portfolio of 350 grants to producer groups engaged in community-based enterprises. USADF is a Federally-funded, public corporation promoting economic development among marginalized populations in Sub-Saharan Africa. USADF impacts 1,500,000 people each year in underserved communities across Africa. Its innovative direct grants program (less than $250,000 per grant) supports sustainable African-originated business solutions that improve food security, generate jobs, and increase family incomes. In addition to making an economic impact in rural populations, USADF’s programs are at the forefront of creating a network of in-country technical service providers with local expertise critical to advancing Africa’s long-term development needs. USADF furthers U.S. priorities by directing small amounts of development resources to disenfranchised groups in hard to reach, sensitive regions across Africa. USADF ensures that critical U.S. development initiatives such as Ending Extreme Poverty, Feed the Future, Power Africa, and the Young African Leaders Initiative reach out to those communities often left out of Africa’s growth story. -

(DMPA-SC) in Benin

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Introduction of Community-Based Provision of Subcutaneous Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (DMPA-SC) in Benin: Programmatic Results Tishina Okegbe,a Jean Affo,b Florence Djihoun,b Alexis Zannou,b Odilon Hounyo,b Gaston Ahounou,c Karamatou Adegnika Bangbola,c Nancy Harrisd Lay community health workers and facility-based health care providers in Benin were trained to administer DMPA-SC safely and effectively in 10 health zones. Community-based DMPA-SC was popular, particularly among new users of contraception, and could help the country achieve its family planning goals. Résumé en français à la fin de l'article. ABSTRACT The Republic of Benin faces high maternal, newborn, and child mortality; low modern contraceptive use; and a critical shortage of health workers. In 2013, the Government of Benin made 3 reproductive health commitments to improve national health indicators, in- cluding expanding provision of family planning services at the community level through task sharing. Since 2016, the Advancing Partners & Communities (APC) project has been helping the Benin Ministry of Health (MOH) provide subcutaneous depot medroxypro- gesterone acetate (DMPA-SC; brand name Sayana Press) through facility-based health care providers and community health workers known as relais communautaires (RCs). DMPA-SC is an easy-to-administer, discreet injectable contraceptive that provides 3 months of protection from pregnancy. Beginning in May 2017, the government introduced DMPA-SC through a phased approach in 10 health zones, which encompassed 149 health centers and 614 villages. Between June 2017 and June 2018, the MOH and APC trained 278 facility-based providers and 917 RCs to provide DMPA-SC, and nearly 11,000 doses were subsequently administered to 7,997 women at facilities and in communities. -

Processus De Recrutement Des Amod

1 Processus de Recrutement des AMOd 001/2016 Le Gouvernement de la République du Bénin a obtenu, du Fonds Mondial pour l’Assainissement (GSF) une subvention de 5 millions de dollar US, pour les cinq ans de mise en œuvre du Programme d’amélioration de l’accès à l’Assainissement et aux Pratiques d’Hygiène en milieu Rural (PAPHyR). L’objectif global de ce programme est de favoriser l’accès durable et équitable des populations démunies des zones rurales aux services d’assainissement, avec de bonnes pratiques d’hygiène en vue d’accélérer l’amélioration de la santé et de la qualité du cadre de vie des communautés pour l’atteinte des cibles OMD et post OMD. Medical Care Development International (MCDI), SELECTION DES 14 COMMUNES POUR LA MISE l’Agence d’Exécution (AE) du programme, met à EN OEUVRE DU PREMIER TOUR DE disposition une partie de ces fonds pour FINANCEMENT subventionner des ONG ou des Associations en qualité d’Agence de Mise en Œuvre déléguée (AMOd) pour l’exécution des activités du Suite à la publication de l’avis n° programme dans les vingt-sept (27) communes de 01/2015/PAPHyR-MCDI relatif à l’Appel à sa zone d’intervention. Manifestation d’Intérêt (AMI) le 17 août 2015 dans le quotidien ‘’La Nation’’, les 27 communes MCDI dispose à ce titre d’une enveloppe de d’intervention du PAPHyR ont envoyé à l’AE leur 1 100 000 dollars US de subvention (pour le dossier de manifestation d’intérêt pour le suivi des premier tour de financement) à répartir dans les activités du programme dans leurs communes quatre (4) départements d’intervention du respectives. -

Les Communes Du Benin En Chiffres

REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN Fraternité – Justice -Travail ********** COMMISSION NATIONALE DES FINANCES LOCALES ********** SECRETARIAT PERMANENT LES COMMUNES DU BENIN EN CHIFFRES 2010 IMAGE LES COMMUNES DU BENIN EN CHIFFRES 2010 1 Préface Les collectivités territoriales les ressources liées à leurs compétences et jusque- un maillon important dans le ministériels, participe de cette volonté de voir les développementdécentralisées sontde la Nation. aujourd’hui La communeslà mises disposer en œuvre de ressources par les départements financières volonté de leur mise en place suffisantes pour assumer la plénitude des missions qui sont les leurs. des Forces Vives de la Nation de février 1990. Les Si en 2003, au début de la mise en effective de la articles 150, 151,remonte 152 et 153à l’historique de la Constitution Conférence du 11 décembre 1990 a posé le principe de leur libre aux Communes représentaient environ 2% de leursdécentralisation, recettes de les fonctionnementtransferts financiers et de5% l’Etat en décentralisation dont les objectifs majeurs sont la promotionadministration de consacrantla démocratie ainsi l’avènementà la base etde lela transferts ont sensiblement augmenté et développement local. représententmatière d’investissement, respectivement 13%aujourd’hui et 73%. En cesdix Depuis dix (10) ans déjà, nos collectivités administration de leur territoire, assumant ainsi environ quatreans vingtd’expérience (80) milliards en matière de F CFA deen lesterritoriales missions quivivent sont l’apprentissage les leurs. Ces missionsde la libre ne dehorsdécentralisation, des interventions l’Etat a transféré directes auxréalisées communes dans sont guère aisées surtout au regard des ces communes. multiples et pressants besoins à la base, face aux ressources financières souvent limitées. doiventCes efforts en prendrede l’Etat la qui mesure se poursuivront pour une utilisation sans nul YAYI Bon a bien pri sainedoute etméritent transparente d’être de salués ces ressources. -

Evaluation Design Report for the Benin Power Compact's Electricity Generation Project and Electricity Distribution Project

FINAL REPORT Evaluation Design Report for the Benin Power Compact's Electricity Generation Project and Electricity Distribution Project March 7, 2018 Christopher Ksoll Kristine Bos Arif Mamun Anthony Harris Sarah Hughes Submitted to: Millennium Challenge Corporation 1099 14th Street, NW Suite 700 Washington, DC 20005 Project Monitor: Hamissou Samari Contract Number: MCC-16-CON-0058 Submitted by: Mathematica Policy Research 1100 1st Street, NE, 12th Floor Washington, DC 20002-4221 Telephone: (202) 484-9220 Facsimile: (202) 863-1763 Project Director: Sarah Hughes Reference Number: 50339.01.200.031.000 This page has been left blank for double-sided copying. BENIN ENERGY II: EVALUATION DESIGN REPORT MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH CONTENTS ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................... VII I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 1 II. OVERVIEW OF THE COMPACT, GENERATION ACTIVITY, AND DISTRIBUTION ACTIVITY ......................................................................................................................................... 5 A. Overview of the Benin Power Compact ..................................................................................... 5 B. Overview of the theory of change .............................................................................................. 9 C. Economic rate of return and -

Wilhelms – Universität Bonn Productivity and Water Use Efficie

Institut für Pflanzenernährung der Rheinischen Friedrich – Wilhelms – Universität Bonn Productivity and water use efficiency of important crops in the Upper Oueme Catchment: influence of nutrient limitations, nutrient balances and soil fertility. I n a u g u r a l – D i s s e r t a t i o n zur Erlangung des Grades Doktor der Agrarwissenschaft (Dr. agr.) der Hohen Landwirtschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich – Wilhelms – Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt im September 2005 von Gustave Dieudonné DAGBENONBAKIN aus Porto-Novo, Benin Referent: Prof. Dr. H. Goldbach Korreferent: Prof. Dr. M.J.J. Janssens Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: Dedication ii Dedication This work is dedicated to: Errol D. B. and Perla S. K. DAGBENONBAKIN, Yvonne DOSSOU-DAGBENONBAKIN, Raphaël S. VLAVONOU. Acknowledgments iii Acknowledgements The participation and contribution of individuals and institutions towards the completion of this thesis are greatly acknowledged and indebted. Foremost my sincere appreciation and thankfulness are extended to my promoter Prof. Dr. Heiner Goldbach for providing professional advice, whose sensitivity, patience and fatherly nature have made the completion of this work possible, he always gave freely of his time and knowledge. I would like to express my profound gratitude to Prof. Dr. Ir. Marc Janssens, for giving me the opportunity to pursue my PhD thesis in IMPETUS Project. His insights criticisms are very useful in improving this work. I am grateful to Prof. Dr. H-W. Dehne for reading this thesis and accepting to be the chairman of my defense. My sincere words of thanks are also directed to Prof. Dr. Karl Stahr of the Institute of Soil Science at the University of Hohenheim for giving me the opportunity to be enrolled as PhD student in his Institute. -

Benin Programme (HRDP)

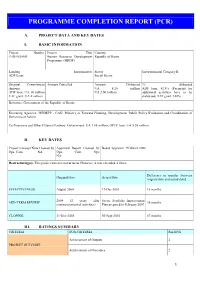

PROGRAMME COMPLETION REPORT (PCR) A. PROJECT DATA AND KEY DATES I. BASIC INFORMATION Project Number Project Title Country P-BJ-IZ0-001 Human Resource Development Republic of Benin Programme (HRDP) Lending Instrument(s) Sector Environmental Category II ADF Loan Social Sector Original Commitment Amount Cancelled Amount Disbursed % disbursed Amount UA 8.28 million ADF loan: 82.8% (Payments for ADF loan: UA 10 million UA 2.00 million additional activities have to be TAF grant: UA 2 million disbursed) TAF grant: 100% Borrower: Government of the Republic of Benin Executing Agencies: MPDEPP - CAG: Ministry of Forward Planning, Development, Public Policy Evaluation and Coordination of Government Action Co-financiers and Other External Partners: Government: UA 1.88 million, OPEC loan: UA 5.58 million II. KEY DATES Project Concept Note Cleared by Appraisal Report Cleared by Board Approval: 15 March 2000 Ops. Com. NA Ops. Com. Ops NA Restructuring(s): This project was not restructured. However, it was extended 4 times. Difference in months [between Original Date Actual Date original date and actual date] EFFECTIVENESS August 2000 17-Dec-2001 16 months 2004 (2 years after Sector Portfolio Improvement MID-TERM REVIEW 36 months commencement of activities) Plan prepared in February 2007 CLOSING 31-Dec-2005 30-Sept-2010 57 months III. RATINGS SUMMARY CRITERIA SUB-CRITERIA RATING Achievement of Outputs 2 PROJECT OUTCOME Achievement of Outcomes 2 1 Timeliness 1 OVERALL PROJECT OUTCOME 2 Design and Readiness 3 BANK PERFORMANCE Supervision 2 OVERALL BANK PERFORMANCE 2 Design and Readiness 2 BORROWER PERFORMANCE Execution 2 OVERALL BORROWER PERFORMANCE 2 IV. RESPONSIBLE BANK STAFF POSITIONS AT APPROVAL AT COMPLETION Regional Director N/A Mr.