4969987-5449F5-5060113443267.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

A Textual and Musical Commentary on J. Guy Ropartz's Quatre

A Textual and Musical Commentary on J. Guy Ropartz’s Quatre Poèmes après l’Intermezzo d’Henri Heine (1899) by Taylor Hutchinson A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved April 2019 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Andrew Campbell, Chair Brian DeMaris Amy Holbrook Russell Ryan ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2019 ABSTRACT Heinrich Heine’s collection of poems, Lyrisches Intermezzo, is well-known in music circles, largely due to Robert Schumann’s settings of sixteen of these poems in his masterwork Dichterliebe. Because of Dichterliebe’s place of importance in art song literature, many other settings of Heine’s sixty-five poems are often overlooked. Breton- born composer Joseph Guy Marie Ropartz composed Quatre Poèmes d’après l’Intermezzo d’Henri Heine in 1899, after having collaborated on a new French translation of the entire Lyrisches Intermezzo in 1890. This cycle is rarely performed, largely due to Ropartz’s relative obscurity as a composer, as the focus of his career was administration of two regional conservatories in France. The Quatre Poèmes were written fairly early in Ropartz’s life, but feature many compositional techniques that remain staples of Ropartz’s work throughout his career. It is an accessible work to many singers and audience members already familiar with Heine. The texts of the four songs are not simply translations of Heine’s original, but altered to adhere to the rules of French poetry. Examining the changes made in the text, both in language and structure, reveals information that will aid performers’ understanding of the poetry and of Ropartz’s choices in musical setting. -

A Discography by Claus Nyvang Kristensen - Cds and Dvds Cnk.Dk Latest Update: 10 April 2021 Label and ID-Number Available; Not Shown

A discography by Claus Nyvang Kristensen - CDs and DVDs cnk.dk Latest update: 10 April 2021 Label and ID-number available; not shown Alain, Jean (1911-1940) Deuxième Fantaisie Marie-Claire Alain (1972) Intermezzo Marie-Claire Alain (1972) Le jardin suspendu Marie-Claire Alain (1972) Litanies Marie-Claire Alain (1972) Suite pour orgue Marie-Claire Alain (1972) Trois danses Marie-Claire Alain (1972) Variations sur un thème de Janequin Marie-Claire Alain (1972) Albéniz, Isaac (1860-1909) España, op. 165: No. 2 Tango in D major Leopold Godowsky (1920) España, op. 165: No. 2 Tango in D major (Godowsky arrangement) Carlo Crante (2011) Emanuele Delucchi (2015) Marc-André Hamelin (1987) Wilhelm Backhaus (1928) Iberia, Book 2: No. 3 Triana (Godowsky arrangement) Carlo Crante (2011) David Saperton (1957) Albinoni, Tomaso (1671-1751) Adagio in G minor (Giazotto completion) (transcription for trumpet and organ) Maurice André, Jane Parker-Smith (1977) Violin Sonata in A minor, op. 6/6: 3rd movement, Adagio (transcription for trumpet and organ) Maurice André, Hedwig Bilgram (1980) Alkan, Charles-Valentin (1813-1888) 11 Grands Préludes et 1 Transcription du Messie de Hændel, op. 66 Kevin Bowyer (2005) 11 Grands Préludes et 1 Transcription du Messie de Hændel, op. 66: No. 1 Andantino Nicholas King (1992) 11 Grands Préludes et 1 Transcription du Messie de Hændel, op. 66: Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11 (da Motta transcription for piano four hands) Vincenzo Maltempo, Emanuele Delucchi (2013) 11 Pièces dans le Style Religieux et 1 Transcription du Messie de Hændel, op. 72 Kevin Bowyer (2005) 13 Prières pour Orgue, op. -

Dossierprofsculpture Version

La sculpture Amédée-René Ménard (1806-1879) Maquette originale du fronton du musée , 1870 Plâtre, 130 x 65 x 35 cm Dossier pour les enseignants Service éducatif du musée des beaux-arts de Quimper La sculpture Sommaire Hall René Quillivic— L’Appel aux marins 3 René Quillivic—La Pointe du Raz 4 René Quillivic— La penn Sardin 4 Jean Armel-Beaufils—Quimper 5 Salle 2—La Bretagne du XIXe siècle Amédée-René Ménard—Le Roi Gradlon 6 Salle 3—Max Jacob et ses amis Charles Million—Buste de Max Jacob 7 Augustin Tuset— Portrait de Jean Moulin 7 Henri Laurens—L’Archange foudroyé 8 Giovanni Leonardi—Vénus et Adonis 9 Giovanni Leonardi— Le Roi Gradlon 10 Salle 14—L’art français fin XVIIIe—début XIXe siècle Anonyme—L’Esclave scythe aiguisant un couteau 11 Anonyme— Les Lutteurs 11 Salle 17—L’art français du XIXe siècle Eugène-Antoine Aizelin—Psyché 12 Léon-Charles Fourquet—Cupidon 13 James Pradier—Jeune Chasseresse au repos 14 Salle 21—L’Ecole de Pont-Aven Georges Lacombe—Buste de Paul Sérusier 15 Paul Gauguin—Tonnelet décoré 16 Paul Gauguin—Gourde de pèlerinage 17 Salle 23—L’art en Bretagne après l’Ecole de Pont-Aven René Quillivic—Brodeuse de Pont-l’Abbé 18 René Quillivic—Petite Bretonne ou La Timide 19 René Quillivic—Aphrodite 19 Salle 22— Sèvres Denys Puech—La Nuit 20 Salle 24—les arts décoratifs Simon Foucault—La Ramasseuse de goémon 20 Francis Renaud—Jeune Bretonne 21 Georges Lacombe—Médaillon de Paul Ranson 15 Les techniques de la sculpture Le modelage / le moulage 22 La fonte 23 La taille 24 Suggestions de parcours à travers les collections Quillivic et la Bretagne 25 La sculpture académique 25 La sculpture commémorative 26 La sculpture ornementale 26 Le corps 27 Le portrait 27 La sculpture dans le patrimoine quimpérois 28 René Quillivic (1879-1969) L’artiste Quillivic naît à Plouhinec, près de la baie d’Audierne, dans une famille de pêcheurs. -

La Complainte Et La Plainte : Chansons De Tradition Orale Et

La complainte et la plainte : chansons de tradition orale et archives criminelles : deux regards crois´essur la Bretagne d'Ancien R´egime(16e-18e si`ecles) Eva Guillorel To cite this version: Eva Guillorel. La complainte et la plainte : chansons de tradition orale et archives criminelles : deux regards crois´essur la Bretagne d'Ancien R´egime(16e-18e si`ecles).Linguistique. Universit´e Rennes 2, 2008. Fran¸cais. <tel-00354696> HAL Id: tel-00354696 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00354696 Submitted on 20 Jan 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. Université européenne de Bretagne Éva Guillorel Université Rennes 2 CERHIO La complainte et la plainte Chansons de tradition orale et archives criminelles : deux regards croisés sur la Bretagne d´Ancien Régime (16e-18e siècles) Volume 1 Thèse de doctorat Département d’histoire 2008 Directeur de recherche : Philippe Hamon Présentée et soutenue publiquement devant un jury composé de MM. Peter Burke, Joël Cornette, Philippe Hamon, Philippe Jarnoux, Donatien Laurent et Michel Nassiet Guillorel, Eva. La complainte et la plainte : chansons de tradition orale et archives criminelles - 2008 De nombreuses personnes m’ont encouragée et aidée au cours de ces trois années de thèse de doctorat d’histoire, ainsi que pendant les années de maîtrise et de DEA qui ont précédé et qui ont permis le mûrissement du sujet de recherche finalement retenu. -

Recital E Paesaggio Urbano Nell'ottocento

RECITAL E PAESAGGIO URBANO NELL’OTTOCENTO CONVEGNO INTERNAZIONALE 11-13 luglio 2013, La Spezia, Italy CAMEC (Centro di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) organizzato da Società dei Concerti, La Spezia Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca in collaborazione con Palazzetto Bru Zane – Centre de musique romantique française, Venezia COMITATO SCIENTIFICO ANDREA BARIZZA (Società dei Concerti della Spezia) RICHARD BÖSEL (Istituto Storico Austriaco, Roma) ROBERTO ILLIANO (Società dei Concerti della Spezia / Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) ÉTIENNE JARDIN (Palazzetto Bru Zane, Venezia) FULVIA MORABITO (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) MASSIMILIANO SALA (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) ROHAN H. STEWART-MACDONALD (Stratford-Upon-Avon, UK) KEYNOTE SPEAKERS RICHARD BÖSEL (Istituto Storico Austriaco, Roma) LAURE SCHNAPPER (École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales-EHESS, Parigi) GIOVEDÌ 11 LUGLIO ore 10.00-10.30: Registrazione e accoglienza 10.30-11.00: Apertura dei lavori • Massimiliano Sala (Presidente Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) • Attilio Ferrero (Presidente della Società dei Concerti) • Étienne Jardin (Coordinatore scientifico Palazzetto Bru Zane, Venezia) • Saluti istituzionali 11.30-12.30: Il Recital solistico: nascita e sviluppo di un genere (Chair: Richard Bösel, Istituto Storico Austriaco, Rome) • MARIA WELNA (Sydney Conservatorium of Music, The University of Sydney, AUS): The Solo Recital – A Lost Performance Tradition • GEORGE BROCK-NANNESTAD (Patent Tactics, -

1 a Succession of Dialogues: François-Marie Luzel and His

A Succession of Dialogues: François-Marie Luzel and his contribution to the Breton Folktale Abstract François-Marie Luzel (1821-1895) was one of the most significant French folklorists of his day and champion of Breton culture. He mainly collected folktales in his native Lower Brittany and published prolifically, including three volumes in the monumental Contes populaires series, published by Maisonneuve and Charles Leclerc in 1887. On the one hand, Luzel was a man of his time, adopting the philosophies and approaches of his fellow folklorists and antiquarians. However, many of his methods, in particular his insistence on authenticity and fidelity to the spoken word, and his realization that traditional cultures are enriched and preserved not through cultural isolation, but by interaction with other cultures, seem out of step with the attitudes of many of his contemporaries and rather seem to anticipate twentieth century developments in folktale collecting practice. Furthermore, Luzel often courted controversy and regularly came into conflict with many of his colleagues in the Breton cultural and political establishment around his insistence on publishing in French and his attitude towards the literary ‘Unified Breton’ and the associated debates around what constituted an authentic Breton culture. 1 This article will place Luzel in his historical context and explore his approach to collecting and publishing his folktales and the controversies he courted. It is followed by a companion piece – a new translation of one of Luzel’s tales – ‘Jannic aux deux sous’ (‘Tuppenny Jack’*) – a Breton variant of ‘The Frog Prince’. Keywords François-Marie Luzel Breton Folk tales Translation Collecting François-Marie Luzel1(1821-1895) was arguably one of the most significant French folklorists of his day and champion of Breton culture, where his influence was substantial in laying the groundwork for the following generation of Breton folklorists, such as Paul Sébillot and Anatole le Braz. -

The Spectacle of Piety on the Brittany Coast

Event Management, Vol. 14, pp. 000–000 1525-9951/10 $60.00 + .00 Printed in the USA. All rights reserved. DOI: 10.3727/152599510X12901814777989 Copyright 2010 Cognizant Comm. Corp. www.cognizantcommunication.com THE SPECTACLE OF PIETY ON THE BRITTANY COAST MAURA COUGHLIN Visual Studies, Bryant University, Smithfield, RI, USA Writing in the early 20th century, sociologist Max Weber found the modern world increasingly “disenchanted”: belief in the magical and sacred had receded to its uncolonized margins. In France, these margins on the Brittany coast drew a seasonal crowd of cultural tourists throughout the 19th century. Artists and writers who journeyed to the coast of Western Brittany were fascinated by the spectacle of local festive displays such as the yearly religious pardons at St. Anne de Palud. But instead of understanding ritual festivities on the Brittany coast as simply the encounter of an outsider and his or her rural other, we can read these events as collective experiences that provided many ways to be both spectacle and spectator. This article departs from previous studies of art in Brittany in two significant ways: it considers the experience of local travel to coastal festivities (such as pardons) rather than taking tourism only to mean travel on a wider national or interna- tional scale. It also widens the focus of previous critical considerations of pardons in paintings to an expanded archive of visual and material culture from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Rather than equating rural life and representations of it with an outsider’s longings for an imagi- nary past, I employ methodologies drawn from feminist cultural criticism and the anthropology of material culture to view Breton pardons and their forms of visual culture as vibrant and ever changing performances and mediations of place and cultural identity. -

Separatism in Brittany

Durham E-Theses Separatism in Brittany O'Callaghan, Michael John Christopher How to cite: O'Callaghan, Michael John Christopher (1982) Separatism in Brittany, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7513/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 1 ABSTRACT Michael John Christopher O'Callaghan SEPARATISM IN BRITTANY The introduction to the thesis attempts to place the separatist movement in Brittany into perspective as one of the various separatist movements with• in France. It contains speculation on some possible reasons for the growth of separatist feeling, and defines terms that are frequently used in the thesis. Chapter One gives an account of Breton history, tracing Brittany's evolution as an independent state, its absorption by France, the disappearartee of its remaining traces of independence, and the last spasms of action to regain this independence after having become merely part of a centralised state. -

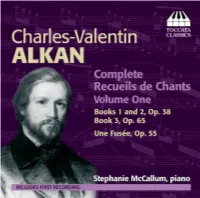

Toccata Classics TOCC0157 Notes

P CHARLES-VALENTIN ALKAN AND HIS RECUEILS DE CHANTS, VOLUME ONE by Peter McCallum Alkan’s ive books of Chants were written over a iteen-year period from 1857 to 1872 during his • Douze études dans les tons mineurs most artistically mature and productive phase, ater he emerged from a period of self-imposed • Cavatina from Beethoven’s String Quartet in B lat major Op.130, arr. Alkan (in social and artistic seclusion. In spite of their expressive variety, they are uniied both internally and over the complete ive-volume cycle, the ith book returning to some of the characteristics • Le Festin d’Ésope of the irst book, ending with a relective summary.1 Unlike the Opp. 35 and 39 studies, they are not the alpha and omega of his achievement, but rather a more subtle and intricate map of the • Symphonie strands and range of his musical thought. It is a characteristic of all of Alkan’s best music that – although he works within the harmonic • Twelve Studies in All the Major Keys and tonal language, the range of genres and the stylistic parameters of the nineteenth century – he brings to each of them a singular personality deined by the sense of far-sighted clarity that • Concerto for solo piano, Op. 39, Nos. 8–10; comes with isolation. Such isolation inds beautiful, poignant and varied expression in G minor Barcarolles that conclude each of the ive volumes of Chants. His sentimental moods (oten found in the E major pieces that open each set) are tinged with yearning and a sense that such comfort is for others; instead, as later with Mahler and Shostakovich, he is haunted by visions of parody, the banal and the grotesque. -

Womenâ•Žs Material Culture of Mourning on the Brittany Coast

Bryant University Bryant Digital Repository English and Cultural Studies Faculty English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles Publications and Research 2009 Crosses, Cloaks and Globes: Women’s Material Culture of Mourning on the Brittany Coast Maura Coughlin Bryant University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bryant.edu/eng_jou Recommended Citation Coughlin, Maura, "Crosses, Cloaks and Globes: Women’s Material Culture of Mourning on the Brittany Coast" (2009). English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles. Paper 42. https://digitalcommons.bryant.edu/eng_jou/42 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English and Cultural Studies Faculty Publications and Research at Bryant Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Bryant Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 15 © Copyrighted Material Crosses, Cloaks, and Globes: Women’s Material Culture of Mourning on the Brittany Coast Maura Coughlin www.ashgate.com www.ashgate.com www.ashgate.com Rural women living on the coast of Brittany, from the mid-nineteenth to mid- twentieth centuries, countered loss of life and social change with mourning rituals and objects that had local and temporal meanings. Three things, the funerary proëlla cross, the widow’s cloak, and the marriage globe, marked rites of passage and served as repositories of individual memory, whether interred, www.ashgate.com worn, or displayed in the home. The material significance of these objects is place-specific: they come from a relatively austere culture, a maritime peasant world of thrift, poverty, and self-reliance. -

Are the Bretons French?

ARE THE BRETONS FRENCH? THE CASE OF FRANÇOIS JAFFRENOU/TALDIR AB HERNIN François Jaffrennou reached adulthood in 1900, in the heyday of both regionalism and pan- Celticism, at the end of a century of nation building. French by birth and by education, he spoke French and published in French. However he also wrote in and lived through other languages: Breton and Welsh, and preferred to go by a Breton name conferred on him by a Welsh Archdruid: Taldir ab Hernin.1 Today he has no biography, and is out of print, but his hybrid œuvre, when approached multilingually, can reveal to us the tensions inherent in Breton identity. One reason why the literatures of Brittany receive very little attention from scholars within French and francophone studies is that ‘regional’ literature has been dismissed as little more than a historical curiosity by scholars whose focus has remained firmly on the avant- garde, and on those writers sanctioned by the Parisian literary scene. Work on regionalism in literature from France has mostly relied on a centre-periphery model, concentrating on the peripheral author’s position vis-à-vis Paris, centre of publishing and maker of literary reputations.2 If attention has shifted away from Paris out onto the whole of la francophonie in recent decades, thanks to postcolonialism, both the regionalist and postcolonial approaches have limitations for understanding a writer such as Taldir. Postcolonialism has usefully taught us to consider all kinds of power relations and their imprint on literary texts, and it has brought some visibility to minority cultures, including Brittany.3 However, early postcolonial criticism tended towards the monolingual, and ‘even the linguistically mute’.4 Also its focus on the cause of minor status frames the cultural battle ‘vertically’, causing us to overlook the ‘lateral networks’ between minority cultures.5 Inter-Celtic relations have fallen outside the scope of both regionalism and postcolonialism, because of the centre-periphery model that is 1 the legacy of nineteenth-century nationalism.