A Textual and Musical Commentary on J. Guy Ropartz's Quatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

ROPARTZ RHENÉ-BATON Trios Avec Piano TRIO HOCHELAGA

ROPARTZ RHENÉ-BATON Trios avec piano TRIO HOCHELAGA ACD2 2542 AT M A Classique Joseph Guy Ropartz (1864-1955) Trio en la mineur pour violon, violoncelle et piano (1918) [36:53] 1 :: I Modérément animé [13:52] 2 :: II Vif [6:02] 3 :: III Lent – Animé [16:59] René-Emmanuel Bâton dit Rhené-Baton (1879-1940) Trio pour piano, violon et violoncelle, op. 31 (1923) [23:33] 4 :: I Lento – Allegro [10:03] 5 :: II Divertissement sur un vieil air breton (Allegro giocoso) [4:14] 6 :: III Andante – Allegro vivace e agitato [9:16] Trio Hochelaga Anne Robert :: VIOLON | VIOLIN Paul Marleyn :: VIOLONCELLE | CELLO Stéphane Lemelin :: PIANO é en 1864 à Guingamp, en Bretagne, Joseph-Guy Ropartz entre en Ropartz compose son Trio pour piano, violon et violoncelle en 1918, vers la contact avec les arts dès sa plus tendre enfance. Son père, avocat, fin de la Première Guerre mondiale, alors qu’il dirige le Conservatoire de Nancy. Naffectionne particulièrement la musique et la littérature. Il est donc Dédiée à Pierre de Bréville, ami et condisciple du compositeur, cette œuvre peu étonnant que toutes deux deviennent les plus grandes passions du porte la marque évidente de l’influence de César Franck, non seulement en rai- fils. Après avoir hésité entre une carrière d’écrivain ou de musicien, le son de sa forme cyclique, affectionnée par le maître, mais également de l’inten- jeune homme décide finalement d’entreprendre des études de droit, sité de ses lignes mélodiques et de la richesse de ses harmonies. obéissant ainsi à sa mère qui refuse de le voir s’engager dans une vie de Pour l’écrire, Ropartz s’est également inspiré de sa Bretagne natale. -

4969987-5449F5-5060113443267.Pdf

GUY ROPARTZ, FRENCH MASTER WITH BRETON ROOTS by Peter McCallum Composer, poet, conductor, novelist and administrator of remarkable energy, Joseph Guy Marie Ropartz (1864–1955) was born – in Guingamp, Côtes-du-Nord, more or less equidistant between Brest and St Malo – into a family of intellectual and artistic breadth and strong civic commitment to the culture and history of his native Brittany. These virtues shaped his music over a long, industrious and productive career, and each of them can be found in part in music included in this recording, which consists of two large-scale suites and a number of shorter pieces. Literary and narrative affinities pervade the two suites, particularly Dans l’ombre de la montagne, which also evokes folk-styles in some of its movements. His father, Sigismond Ropartz, was a lawyer, poet and enthusiastic chronicler of Breton history. After Sigismond’s death in 1879, Joseph studied in a Jesuit college at Vannes, where he learnt the bugle, French horn, double-bass and percussion and consolidated a profound Catholic faith. In deference to his mother’s wishes, he pursued training in law at Rennes, where he met Breton writer Louis Tiercelin and other artists interested in the Breton cultural revival. Ropartz joined the Breton Regionalist Union, a cultural organisation founded in 1898 and dedicated to preserving Breton culture and regional independence. He used the words of several Breton writers in musical settings, including Anatole Le Braz and Charles le Goffic. Although admitted to the bar in 1885, he does not seem to have ever practised law as a profession. -

TOCN0007DIGIBKLT.Pdf

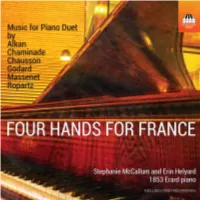

FOUR HANDS FOR FRANCE Music for Piano Duet ERNEST CHAUSSON Sonatines pour quatre mains, Op. 2 (1879)* 20:53 Sonatine No. 1 in G major (1878) 6:24 1 I Gaîment 1:37 2 II Andante 2:59 3 III Finale 1:48 Sonatine No. 2 in D minor (1879) 14:29 4 I Mouvement de marche 4:52 5 II Variations sur un thème danois, transcrit par Niels Gade 5:44 6 III Rondeau-Allegretto 3:53 GUY ROPARTZ Petites Pièces (1903)* 25:30 Pour Gaud 7 No. 1 Andante 1:35 8 No. 2 Lento 1:31 9 No. 3 Allegretto 1:06 Sons de Cloches 10 No. 4 L’Angelus 3:18 11 No. 5 Le Glas 3:36 12 No. 6 Cloches du Soir 3:17 *** 13 No. 7 Choral 3:35 14 No. 8 Tristesse 1:37 15 No. 9 Intimité 2:24 16 No. 10 Par les Champs 3:31 2 JULES MASSENET Pièces pour le Piano à 4 Mains: 1re Suite, Op. 11 (1867)* 8:14 17 No. 1 Andante 2:55 18 No. 2 Allegretto quasi allegro 3:13 19 No. 3 Andante 2:06 CHARLES-VALENTIN ALKAN 20 Saltarelle, Op. 47 (1856) 7:03 CÉCILE CHAMINADE Pièces romantiques, Op. 55 (1890) 21 No. 1 Primavera 2:41 22 No. 3 Idylle arabe 2:43 23 No. 4 Sérénade d’automne 2:59 BENJAMIN GODARD Deux morceaux, Op. 137 (1893)* 2:45 24 No. 1 Pastorale mélancolique 1:39 25 No. 2 Marche villageoise 1:06 Stephanie McCallum (primo) and Erin Helyard (secondo) TT 72:51 Piano Erard 1853 * FIRST RECORDINGS 3 FOUR HANDS FOR FRANCE: MUSIC FOR PIANO DUET Stephanie McCallum Our starting point is in France. -

Breton Identity in the Poetry Anthology, 1830–2000 David

MYTHS OF AUTHENTICITY AND CULTURAL PERFORMANCE: BRETON IDENTITY IN THE POETRY ANTHOLOGY, 1830–2000 DAVID EVANS In the preface to his anthology Poètes de Bretagne of 1979, Charles Le Quintrec wrings his hands at the state of contemporary French poetry. He is especially scornful of Parisian cliques, with ‘leurs petits cocktails, leurs petits plaisirs, leurs tables rondes radiophoniques et leurs dîners-débats’, petty concerns which have reduced the art form to mere word games.1 The poets of Brittany, he argues, are fundamentally different people: Les poètes armoricains ont toujours cherché le contact des hommes. Ils n’ont pas écrit pour leur propre satisfaction, pour leurs plaisirs piégés, mais pour les autres, pour essayer d’aller voir ensemble ce qu’il y a dans la lumière et encore derrière la lumière du menhir et de la fontaine. C’est en cela, essentiellement, que les poètes d’Armor sont différents des poètes français et surtout des poètes parisiens qui aiment tellement se transformer en parfumeurs. Sur nos landes, on se moque pas mal de sentir bon! […] Il n’y a pas de parfumeurs, ni de joyeux drilles, ni de divins bouffons chez les poètes de la lande. La grande majorité d’entre eux est incapable de vous ficeler quelques acrostiches et ne savent pas les lais pour les reines. De leur ignorance monte un chant plus âpre, plus instinctif, et, je serais tenté de dire, plus authentique. (pp. 16– 17) Le Quintrec mobilizes all the clichés which have accumulated in literary representations of Breton authenticity: rootedness in place, an intense affective relationship with the environment, a sense of community and solidarity, singularity of purpose, an essential difference. -

Livret Ropartz

opSta éphrtzane Lemelin R piano e u q i s s a l C ACD 2 2255 ATMA StéphJaonesLempelhin – pGianouy Ropa(18r64-1t955z ) MUsiqUes aU jardin (1916-1917 – à Colette et HUgUette LUc) 18:34 1 PrélUde matinal 3:39 2 Un oiseaU sUr le sable de l’allée… 2:01 3 Les vieUx soUvenirs sUrgissent de l’ombre… 3:31 4 Un enfant joUe… 1:09 5 Le jardin aU CrépUscUle… 3:50 6 Rondes et Chants 4:24 7 NoctUrne (1911 – à Germaine Adrien) 11:25 8 DeUxième NoctUrne (1916 – à Blanche Selva) 9:55 9 Troisième NoctUrne (1916 – à JacqUes DUrand) 4:41 10 Scherzo (1916 – à ÉdoUard Risler) 4:29 JeUnes Filles – cinq esqUisses poUr piano (1929) 17:31 11 L’InsoUciante (à Robert CasadesUs) 2:41 Enregistrement et réalisation / Recorded and produced by: Johanne Goyette Salle Pierre-MercUre, Montréal (QUébec) 12 La Nonchalante (à Nathalie Radisse) 3:16 15, 16, 17 janvier 2001 / January 15, 16, 17, 2001 Montage nUmériqUe / Digital Mastering: Anne-Marie Sylvestre, StUdio l'Esplanade 13 La CoqUette (à Hélène Pignari) 4:08 Adjoints à la prodUction / Production assistants: Valérie Leclair, JacqUes-André HoUle 14 La Tendre (à Andrée VaUraboUrg) 5:02 Graphisme / Graphic design: Diane Lagacé CoUvertUre / Cover: Georges SeUrat, La grève du Bas Butin à Honfleur, 1886 15 La CapricieUse (à Marcel Ciampi) 2:24 poète breton on nom s’est écrit de plUsieUrs façons : Ô mer immense, mer aux rumeurs monotones, opJosepa h GUyrtzMarie Ropartz, Tu berças doucement mes rêves printaniers; SJoseph GUy Ropartz, Ô mer immense, mer perfide aux mariniers, R Joseph GUy-Ropartz, Sois clémente aux douleurs sages de mes automnes. -

Jean Devã©My and the Paris Conservatory Morceaux De

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Jean Devémy and the Paris Conservatory Morceaux de Concours for Horn, 1938-1969 Emily Britton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC JEAN DEVÉMY AND THE PARIS CONSERVATORY MORCEAUX DE CONCOURS FOR HORN, 1938-1969 By EMILY ADELL BRITTON A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2014 Emily A. Britton defended this treatise on October 12, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Michelle Stebleton Professor Directing Treatise Jane Piper Clendinning University Representative Christopher Moore Committee Member Richard Clary Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks are due to the members of my committee, Dr. Clendinning, Dr. Moore, and Professor Clary, for their support and advice during my time at FSU. I owe a debt of gratitude to my horn teacher and academic advisor, Professor Stebleton, who spent countless hours helping and directing me. I am indebted to three strangers across the ocean who took the time to answer questions about my topic: Vincent Andrieux, Daniel Bourgue, and Claude Maury. The information they provided was invaluable. I am also grateful to friends who encouraged me not to give up after so many years away from academia, particularly my shop supervisor, John Garcia, who never scolded me for writing my treatise at work. -

An Evaluation of Orchestral Conducting Teaching Methods

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Learning and teaching conducting through musical and non-musical skills: an evaluation of orchestral conducting teaching methods Jose Mauricio Valle Brandao Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Brandao, Jose Mauricio Valle, "Learning and teaching conducting through musical and non-musical skills: an evaluation of orchestral conducting teaching methods" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3954. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3954 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. LEARNING AND TEACHING CONDUCTING THROUGH MUSICAL AND NON-MUSICAL SKILLS: AN EVALUATION OF ORCHESTRAL CONDUCTING TEACHING METHODS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by José Maurício Valle Brandão B.M., Universidade Federal da Bahia, 1994 M. M., Universidade Federal da Bahia, 1999 Ph. D., Universidade Federal da Bahia, 2009 August, 2011 To my wife, Blandina; to my friend, Vladimir; to my advisor, Bill Grimes – none of you let me give up. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to acknowledge and thank the Louisiana State University and the Huel Perkins Fellowship for giving me the opportunity to study conducting in the United States. -

J. Guy Ropartz Ou La Recherche D'une Vocation

ENYSS DJEMIL J. Guy Ropartz ou la recherche d'une Vocation L'œuvre littéraire du Maître et ses résonances musicales IMPRIMERIE JEAN VILAIRE LE MANS 1 9 6 7 A Gaud ROPARTZ J. GUY ROPARTZ ou LA RECHERCHE D'UNE VOCATION ENYSS DJEMIL \ J. Guy Ropartz ou la recherche d'une Vocation L'œuvre littéraire du Maître et ses résonances musicales IMPRIMERIE JEAN VILAIRE LE MANS 9 6 7 « Les belles âmes, ce sont les âmes universelles, ouvertes et prestes à tout... » MONTAIGNE Avant-propos Au moment où j'entreprenais cette étude (1), près de huit années s'étaient écoulées depuis la mort du regretté maître Guy Ropartz (2). C'était suffisant pour que mon immense admiration puisse volontairement s'effacer et céder la place à un jugement objectif sur l'homme et sur son œuvre. Depuis, une intéressante exposition a été organisée sous la direction de M'"" Lebeau, conservateur en chef du département de la Musique à la Bibliothèque Nationale, et avec les soins diligents de Mil' Wallon (3). Des conférences et des concerts auxquels j'ai participé ont eu lieu, dans plusieurs villes, grâce aux encouragements du Comité du Centenaire de la naissance de Guy Ropartz et, en particulier, sous l'impulsion de son actif président, Jacques Feschotte (4). Puissent ces manifestations avoir contribué à mieux faire connaître une des personnalités les plus marquantes de notre temps 1 C'est également le vœu poursuivi dans la présente étude. Celle-ci s'adresse, toutefois, à des lecteurs spécialement intéressés par les recherches littéraires et, en particulier, aux universitaires de la Faculté des Lettres et Sciences humaines de Rennes. -

Reading with Provincial Eyes: the French Musical Press Beyond the Capital

Reading with Provincial Eyes: The French Musical Press beyond the Capital Katharine Ellis (University of Cambridge) [email protected] The centralised nature of France in the nineteenth century and beyond encourages the assumption that its towns are simply pale and small-scale versions of the capital. On close inspection this assumption proves to be illusory in various ways: firstly, there comes a point when Paris is simply not scalable; secondly, we find decentralist or regionalist resistance to Parisian norms; thirdly, local conditions spark local initiatives that have little to do with models available elsewhere, whether in the capital or not. As published in the daily papers or in specialist periodicals, music criticism is no exception to this phenomenon. When the hundreds of critics who worked in the capital are reduced to a few influential names, the ramifications for critique and debate are radically different. Local rivalries are lived out in greater relief, meaning that losers pay a higher price; by extension, the relationship between writers, local musicians and readers is more intimate, and more obviously so. Among specialist publications, the relative absence of publisher journals and competing titles makes for a less rampantly commercial arena; instead, questions of local solidarity and aspiration loom large. Relations with Paris itself need careful handling. Matters of local pride reach peak intensity not locally but in the breathless dialogue of regional correspondents and their editors in Paris, where «Nouvelles» columns often present French provincial music-making through rose-tinted glasses. Finally, discourses that might in Paris seem self-evidently important for the whole of France become transformed or even displaced on account of the regional, or municipal, coverage of each publication1.