The Spectacle of Piety on the Brittany Coast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Étude Sur La Dynamique Des Territoires Ruraux

ÉTUDE SUR LA DYNAMIQUE DES TERRITOIRES RURAUX DIAGNOSTIC ET DÉFINITION DES ENJEUX DU TERRITOIRE Territoires de la communauté de communes du Cap-Sizun Pointe du Raz et de Douarnenez Communauté RAPPORT Direction départementale des territoires et de la mer du Finistère 2/54 TABLE DES MATIÈRES 1- MÉTHODE D’ÉLABORATION DU DOCUMENT 2- DIAGNOSTIC 2-A : Des paysages maritimes emblématiques et des paysages ruraux bocagers porteurs d’une forte identité locale 2-B : Une implantation urbaine diffuse marquée par une linéarité et un mitage 2-C : Des risques naturels en lien avec la façade maritime et aggravés par les phénomènes d’érosion et de ruissellement d’eau issu de l’intérieur du territoire 2-D : Un territoire âgé, en perte de vitesse, et au marché de l’habitat relativement détendu 2-E : Un territoire à l’écart des grands axes et infrastructures de transport dont le maillage routier stabilisé a néanmoins impulsé un usage massif de la voiture et généré une proximité pour les déplacements 2-F : Une économie diversifiée et complémentaire, mais fragile, et dont la mer représente un fort atout économique 2-G : Un niveau d’équipement qui compense l’éloignement, mais des carences à souligner à l’extrême ouest, et un niveau en spécialistes de santé faible 3- DIAGNOSTIC TERRITORIAL PARTAGÉ ET SPATIALISÉ : SYNTHÈSE 4- POINT DE VUE DE LA DDTM SUR LES ENJEUX DU TERRITOIRE 4-A : Préserver et valoriser les espaces naturels et les paysages comme levier de développement économique et d’attractivité du territoire 4-B : Enrayer l’urbanisation diffuse et linéaire, -

Bonfire Night

Bonfire Night What Is Bonfire Night? Bonfire Night remembers the failed attempt to kill the King of England and the important people of England as they gathered for the State Opening of Parliament on 5th November 1605. Bonfires were lit that first night in a joyful celebration of the King being saved. As the years went by, the burning of straw dummies representing Guy Fawkes was a reminder that traitors would never successfully overthrow a king. The Gunpowder Plot After Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603, the English Catholics were led to believe that the Act of terrorism: new King, James I, would be more accepting Deliberate attempt to kill of them. However, he was no more welcoming or injure many innocent of Catholic people than the previous ruler people for religious or which led some people to wish he was off the political gain. throne to allow a Catholic to rule the country. A small group of Catholic men met to discuss what could be done and their leader, Robert Catesby, was keen to take violent action. Their plan was to blow up the Houses of Parliament, killing many important people who they did not agree with. This was an act of terrorism. They planned to kill all of the leaders who were making life difficult for the Catholic people. They recruited a further eight men to help with the plot but as it took form, some of the group realised that many innocent people would be killed, including some who supported the Catholic people. This led some of the men to begin to have doubts about the whole plot. -

A History of the Prepare, Stay and Defend Or Leave Early Policy in Victoria

A History of the Prepare, Stay and Defend or Leave Early Policy in Victoria A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Thomas Reynolds Master of Arts (History) Bachelor of Arts (History) School of Management College of Business RMIT University February 2017 1 Declaration I certify that except where due acknowledgement has been made, the work is that of the author alone; the work has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award; the content of the thesis is the result of work which has been carried out since the official commencement date of the approved research program; any editorial work, paid or unpaid, carried out by a third party is acknowledged; and, ethics procedures and guidelines have been followed. Benjamin Thomas Reynolds February 2017 i Acknowledgements This PhD was made possible due to the support of my family, friends and supervisors and the guidance and encouragement I received from each. I would like to thank my parents in particular for again supporting me in my studies, and my supervisors Professor Peter Fairbrother, Dr Bernard Mees, and Dr Meagan Tyler and other colleagues in the School of Management for their reassurances, time, and advice. I would also like to thank the Bushfire and Natural Hazards Cooperative Research Centre for their generous financial support for the project, and in particular Annette Allen and Lyndsey Wright for their encouragement along the way. I would also like to acknowledge the support of John Schauble of Emergency Management Victoria, without whose support the thesis would not have been possible. -

Samhain Quest Pack

Pagan Federation presents Aether Patches Samhain Quest This quest pack has been designed to help children understand more about the festival of Samhain, both its meaning and tra- ditions as well as some correspondences. Suggested challenge levels for different ages: Choose your challenges from across the 5 senses Amethyst (3-5 Years) : Complete a minimum of 3 challenges. Topaz (6-9 Years) : Complete a minimum of 5 challenges. Emerald (10-14 Years) : Complete a minimum of 7 challenges. Ruby (14-18 Years) : Complete a minimum of 10 challenges. Diamond (Over 18s) : Complete a minimum of 13 challenges or award yourself a badge for assisting young people in achieving the quest. Once completed feel free to award the certificate and patch from our website www.pfcommunity.org.uk Sight Challenges Sight challenges are often about looking up information and learning about something new, something relating to this quest. Sometimes they are just about using your eyes to see what you can see Samhain means ‘Summers end’ and is the time when nature starts winding down to rest. Look up and learn about different ways nature rests, such as hibernation. How do you take time to rest? Samhain is associated with Crone Goddesses. Look up and learn about these different deities, don’t forget to write them down in your journal. Samhain marks the end of summer and beginning of winter. Go for a walk in the woods or through a park and notice how the seasons are changing. Write it down in your journal. Samhain is a time to honour our ancestors. -

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite Mass Structures Orientation Language The purpose of this presentation is to prepare you for what will very likely be your first Traditional Latin Mass (TLM). This is officially named “The Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” We will try to do that by comparing it to what you already know - the Novus Ordo Missae (NOM). This is officially named “The Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” In “Mass Structures” we will look at differences in form. While the TLM really has only one structure, the NOM has many options. As we shall see, it has so many in fact, that it is virtually impossible for the person in the pew to determine whether the priest actually performs one of the many variations according to the rubrics (rules) for celebrating the NOM. Then, we will briefly examine the two most obvious differences in the performance of the Mass - the orientation of the priest (and people) and the language used. The orientation of the priest in the TLM is towards the altar. In this position, he is facing the same direction as the people, liturgical “east” and, in a traditional church, they are both looking at the tabernacle and/or crucifix in the center of the altar. The language of the TLM is, of course, Latin. It has been Latin since before the year 400. The NOM was written in Latin but is usually performed in the language of the immediate location - the vernacular. [email protected] 1 Mass Structure: Novus Ordo Missae Eucharistic Prayer Baptism I: A,B,C,D Renewal Eucharistic Prayer II: A,B,C,D Liturgy of Greeting: Penitential Concluding Dismissal: the Word: A,B,C Rite: A,B,C Eucharistic Prayer Rite: A,B,C A,B,C Year 1,2,3 III: A,B,C,D Eucharistic Prayer IV: A,B,C,D 3 x 4 x 3 x 16 x 3 x 3 = 5184 variations (not counting omissions) Or ~ 100 Years of Sundays This is the Mass that most of you attend. -

Situation À Plogoff Perspectives Stratėgie Du

Hebdomadaire du Parti Socialiste Unifié N°879 14 au 20 Février 1981 p.I à III cycliquement avec l’actualité et hexagonale. SITUATION la mobilisation ; 10 à 30 partici- À PLOGOFF pants de manière continue, mais LE POUVOIR ET EDF fonctionnement et composition Semblent vouloir préparer le PERSPECTIVES très variable (politiques, écolos, terrain pour des offensives psy- STRATĖGIE DU ou antinucléaires locaux). chologiques et des opérations de La coordination veut s’affir- charme : PSU-BRETAGNE mer politiquement (manif contre • Propagande : « Nucléaire... Marchais à Brest) et comme chantier... emplois locaux et (texte destiné à provoquer une mouvement de masse ; quelques réflexion au sein du PSU-BRE- chances pour l’éconmie régio- réflexes anti-organiisations, nale : partageons le gâteau TAGNE légèrement remanié mais l’action anti-nucléaire du pour paraître dans TS) puisque c’est décidé ». P.S.U. est bien perçue. • Réunion avec les notables UNE SENSIBILISATION • Mise en place de collectifs pour créer la division et le défai- IMPORTANTE APRÈS LE d’organisations (style pétitions tisme, à propos des procédures DĖCRET D’UTILITÉ PU- énergie) à Brest, Douarnenez juridiques et la mise en place BLIQUE (début décembre 80). et Quimper, extension probable du chantier et équipements an- dans d’autres grandes villes. nexes. • A Plogoff et dans le Cap Sizun : • Important travail des groupes des actions (occupation des énergies nouvelles, installations PARTIS POLITIQUES bureaux EDF à Clamart), inter- pratiques dans la foulée du Pro- pellation des élus pronucléaires, jet Alter Breton, exposition du • PC toujours pro-nucléaire (cf. cerfs volants et ballons sondes matériel et info, notamment en discours de Marchais à Brest et pour la défense du site, mani- milieu rural (danger : transfor- à Rennes), mais questions chez festation symbolique contre une mation des anti nucléaires en les milliants de base qui se sen- maison achetée par EDF, un lé- bricoleurs, représentants locaux tent proches des anti-nucléaires. -

Pilgrimage Processions, Religious Sensibilities and Piety in the City Of

Pilgrimage Processions, Religious Sensibilities and Piety in the City of Acre in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem Peregrinaciones, sensibilidades religiosas y piedad en la ciudad de Acre del Reino latino de Jerusalén Peregrinações, sensibilidades religiosas e piedade na cidade de Acre do Reino Latino de Jerusalém Shlomo LOTAN1 Resumen: Después de la caída de Jerusalén en 1187, Acre se convirtió en la capital formal de la cruzada de la cristiandad. Durante el siglo XIII, se convirtió en lugar de peregrinaje para los cristianos, quienes, a su vez, enriquecieron la ciudad con las ceremonias religiosas que aportaron. Esta procesión se ha denominado Perdón de Acre y ha contribuido notablemente al entendimiento que hoy tenemos de los lugares religiosos y de los grupos militares situados en la Acre franca. Es por ello que en este ensayo pretendo revisitar estos eventos para aportar nueva luz a la comprensión de los lugares religiosos, peregrinaciones y grupos militares que participaron en tan señalado momento. Palabras clave: Cruzadas – Reino latino de Jerusalén – Acre – Peregrinación – Órdenes militares – Hospitalarios – Templarios – Orden Teutónica. Abstract: After the fall of Jerusalem in 1187, Acre became the formal capital of the Crusader Kingdom. During the 13th century, it became a pilgrimage site for many Christian pilgrims, who enriched the city with their religious ceremonies. Such as a procession called the Pardon d'Acre, which contributed greatly to our understanding of the religious places and military compounds in Frankish Acre. In this essay, I link the religious ceremonies that took place in Acre with the passages among the locations mentioned therein. All these contributed to the revival of the historical and religious space in medieval Acre. -

Love Is Creative Even to Infinity: on the Eucharist in the Vincentian Tradition

Vincentiana Volume 47 Number 2 Vol. 47, No. 2 Article 9 3-2003 Love is Creative Even to Infinity: On the ucharistE in the Vincentian Tradition Robert P. Maloney C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Maloney, Robert P. C.M. (2003) "Love is Creative Even to Infinity: On the ucharistE in the Vincentian Tradition," Vincentiana: Vol. 47 : No. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol47/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Love is Creative Even to Infinity — On the Eucharist in the Vincentian Tradition — by Robert P. Maloney, C.M. Superior General Within our Family, we often cite the saying of St. Vincent: “Love is creative even to infinity.”1 Ordinarily, we use this citation to motivate others to be creative pastorally, to respond to new forms of poverty, to be inventive in new formation programs for lay leaders and for the clergy, to investigate ways of rooting out the causes of poverty. But apt as this rhetorical use of Vincent’s words might be, their actual context was quite different. They refer to the institution of the Eucharist. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

Bulletin Municipal • Juillet 2016

Plogoff infos bulletin municipal • juillet 2016 • Le mot du Maire - p. 2 • Services - p. 3 • Vie municipale - p. 4 D’ESTIENNE D’ORVES ET PIERRE BROSSOLETTE • Culture - Bibliothèque - p. 6 • Vie associative - p. 8 • Sécurité Routière - p. 12 ET SI ON REPASSAIT LE CODE ? • Patrimoine - p. 14 LAVOIRS, FOURS A GOÉMON... • Pointe du Raz - p. 16 • Infos pratiques - p. 18 services LE POINT SUR LES TRAVAUX Le mot du Maire • LOTISSEMENT HAMEAU DE LESTRIVIN Les travaux de viabilisation sont terminés. Pour le moment 2 permis de construire ont été accordés. Deux terrains ont été rétrocédés à HABITAT 29 pour la réalisation de 2 logements sociaux pour l’année 2017. Les enfants vont être bientôt en vacances et nous et le transfert des charges financières supplémen- leur souhaitons à tous de bonnes vacances. Mais taires, les élus garants de la cohésion sociale ont dès maintenant, les parents et nous-mêmes devons une nécessité qu’ils n’ignorent pas : celle de four- penser à la rentrée. Vous le savez, c’est une de nos nir au jour le jour des moyens solides d’assurer la préoccupations principales et constantes. tenue de la maison commune en distinguant entre Améliorer la vie de notre école, faciliter l’exis- le but, la fin et le sens. tence quotidienne des élèves par le ramassage, le Bien que le budget école représente 33% du transport scolaire, la garderie, le restaurant scolaire budget global de fonctionnement et contrairement sans oublier le temps d’activité péri-scolaire : quoi à ceux qui, pas particulièrement versés dans l’expé- de plus important ? rience politique, souhaitent faire prendre un risque Toujours un peu émouvante pour les enfants, dont ils ignorent tout à la commune en réclamant la rentrée scolaire l’est aussi pour les parents toujours plus et tout de suite, les élus du conseil qui s’inquiètent, à juste titre, de l’avenir de leur municipal unanimes ont souhaité montrer leur en- progéniture. -

Year of Faith Pardon and Peace Booklet (PDF)

Pardon and Peace Fr. Tom Knoblach YEAR OF FAITH October 11, 2012—November 24, 2013 “Pour out your hearts before him, Conclusion for God is our refuge.” Psalm 62:9 The Letter to the Hebrews sums up well the extraordinary gift of the Introduction Sacrament of Reconciliation when it exhorts us: As the Church prepared to celebrate the beginning of the Third Millennium of the Christian faith, Pope John Paul II asked the faithful to We have a great high priest who has passed through the reflect personally and deeply on the meaning of the Good News of heavens, Jesus, the Son of God. Let us hold fast to our profession salvation, the Gospel of Jesus Christ. As St. Mark tells us, Jesus began his of faith. For we do not have a high priest who is unable to public ministry with the words: “The reign of God is at hand! Reform sympathize with our weakness, but one who was tempted in your lives and believe in the Gospel!” (Mark 1:15). every way that we are, yet never sinned. So let us confidently approach the throne of grace to receive mercy and favor and to We know that the promised coming of the reign of God was fulfilled in find help in time of need. Hebrews 4:14-16 the weakness of the Cross. Through the sacrifice of his life at Golgotha, the Son of God redeemed us from the power of sin and death. When he God, the Father of mercies, through the appeared to his apostles after his resurrection, he gave them his own death and resurrection of his Son has Spirit through whom the work of redemption would continue until his reconciled the world to himself and sent return at the end of time. -

Mise En Page

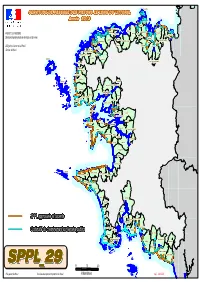

ILE-DE-BATZILE-DE-BATZILE-DE-BATZILE-DE-BATZILE-DE-BATZILE-DE-BATZILE-DE-BATZ SERVITUDESERVITUDE DEDE PASSAGEPASSAGE DESDES PIETONSPIETONS LELE LONGLONG DUDU LITTORALLITTORAL AnnéeAnnée 20132013 ROSCOFFROSCOFFROSCOFF SANTECSANTECSANTEC BRIGNOGAN-PLAGESBRIGNOGAN-PLAGESBRIGNOGAN-PLAGES PLOUESCATPLOUESCATPLOUESCAT KERLOUANKERLOUANKERLOUAN SAINT-POL-DE-LEONSAINT-POL-DE-LEONSAINT-POL-DE-LEON KERLOUANKERLOUANKERLOUAN CLEDERCLEDERCLEDER PLOUGASNOUPLOUGASNOUPLOUGASNOU PREFET DU FINISTERE PLOUNEOUR-TREZPLOUNEOUR-TREZPLOUNEOUR-TREZ CLEDERCLEDERCLEDER SIBIRILSIBIRILSIBIRIL LOCQUIRECLOCQUIRECLOCQUIRECLOCQUIREC GUIMAECGUIMAECGUIMAEC PLOUGOULMPLOUGOULMPLOUGOULM GUIMAECGUIMAECGUIMAEC Direction départementale des territoires et de la mer CARANTECCARANTECCARANTEC GOULVENGOULVENGOULVEN TREFLEZTREFLEZTREFLEZ GUISSENYGUISSENYGUISSENY GOULVENGOULVENGOULVEN TREFLEZTREFLEZTREFLEZ SAINT-JEAN-DU-DOIGTSAINT-JEAN-DU-DOIGTSAINT-JEAN-DU-DOIGT PLOUNEVEZ-LOCHRISTPLOUNEVEZ-LOCHRISTPLOUNEVEZ-LOCHRIST SAINT-JEAN-DU-DOIGTSAINT-JEAN-DU-DOIGTSAINT-JEAN-DU-DOIGT PLOUGUERNEAUPLOUGUERNEAUPLOUGUERNEAU PLOUNEVEZ-LOCHRISTPLOUNEVEZ-LOCHRISTPLOUNEVEZ-LOCHRIST HENVICHENVICHENVIC PLOUEZOCHPLOUEZOCHPLOUEZOCH LANDEDALANDEDALANDEDALANDEDA PLOUIDERPLOUIDERPLOUIDER PLOUENANPLOUENANPLOUENAN Délégation à la mer et au littoral PLOUIDERPLOUIDERPLOUIDER PLOUENANPLOUENANPLOUENAN LOCQUENOLELOCQUENOLELOCQUENOLELOCQUENOLE LANNILISLANNILISLANNILISLANNILIS SAINT-PABUSAINT-PABUSAINT-PABU LANNILISLANNILISLANNILISLANNILIS Service du littoral TAULETAULETAULE LAMPAUL-PLOUDALMEZEAULAMPAUL-PLOUDALMEZEAULAMPAUL-PLOUDALMEZEAULAMPAUL-PLOUDALMEZEAU