A History of the Prepare, Stay and Defend Or Leave Early Policy in Victoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bonfire Night

Bonfire Night What Is Bonfire Night? Bonfire Night remembers the failed attempt to kill the King of England and the important people of England as they gathered for the State Opening of Parliament on 5th November 1605. Bonfires were lit that first night in a joyful celebration of the King being saved. As the years went by, the burning of straw dummies representing Guy Fawkes was a reminder that traitors would never successfully overthrow a king. The Gunpowder Plot After Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603, the English Catholics were led to believe that the Act of terrorism: new King, James I, would be more accepting Deliberate attempt to kill of them. However, he was no more welcoming or injure many innocent of Catholic people than the previous ruler people for religious or which led some people to wish he was off the political gain. throne to allow a Catholic to rule the country. A small group of Catholic men met to discuss what could be done and their leader, Robert Catesby, was keen to take violent action. Their plan was to blow up the Houses of Parliament, killing many important people who they did not agree with. This was an act of terrorism. They planned to kill all of the leaders who were making life difficult for the Catholic people. They recruited a further eight men to help with the plot but as it took form, some of the group realised that many innocent people would be killed, including some who supported the Catholic people. This led some of the men to begin to have doubts about the whole plot. -

TD-1464S Publication Date: 7/20/2021 Rev: 3

Based on Standard: TD-1464S Publication Date: 7/20/2021 Rev: 3 Wildfire Prevention Contract Requirements SUMMARY PG&E’s standard establishes precautions for PG&E employees, PG&E suppliers, contractors, and third-party employees to follow when traveling to, performing work, or operating outdoors on any forest, brush, or grass-covered land. The information in this document is based on PG&E’s TD 1464s standard and local, state, and federal fire regulations and permits. However, if a local or state fire regulation or permit contains provisions more stringent than those in this document, the more stringent provisions must be followed. TARGET AUDIENCE This "based on TD-1464s" document targets all contractors performing work on behalf of PG&E and working on or near facilities located in any forest, brush, or grass-covered lands, using equipment, tools, and/or vehicles whose use could result in the ignition of a fire. This includes those areas that may seem urban but have vegetation that can aid in the spread of an ignition. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Title Page 1 Safety ................................................................................................................ 1 2 General Requirements ...................................................................................... 2 3 Fire Index Process ............................................................................................ 7 4 Mitigations ......................................................................................................... 8 5 Quality Reviews ................................................................................................ 9 REQUIREMENTS 1 Safety 1.1 Performing utility work on any forest, brush, or grass-covered lands presents a danger of fire, in addition to the hazards inherent to utility work. 1.2 Following the directives in this standard are essential to mitigating fire danger and protecting the environment, the utility system, personnel, and the public. PG&E Internal ©2021 Pacific Gas and Electric Company. -

Fire Safety Trailer Curriculum

U.S. Fire Administration Acknowledgements Preparation of this Fire Safety Trailer Curriculum was made possible thanks to the cooperation and hard work of numerous firefighters, public information officers, public education coordinators, and staff of local fire departments and state fire marshal’s offices throughout the United States who contributed countless hours to review, test, and critique this curriculum. The results of their feedback and dedication will help fire safety professionals nationwide develop fire safety education and prevention programs designed to reduce fire-related injury and mortality rates suffered throughout the country. Development of the curriculum was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) under Contract No. 200-2007-21025 to Information Ventures, Inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i–1 What’s in This Curriculum? i–1 How to Use This Curriculum i–2 Before Your Fire Safety Trailer Event i–2 During Your Fire Safety Trailer Event i–3 After Your Fire Safety Trailer Event i–4 1 HOW TO GET FUNDING FOR A TRAILER 1–1 Fire Prevention And Safety (FP&S) Grant 1–1 Grant Writing Tips 1–2 Getting Organized To Write Your Grant Application 1–4 Preparing Your Fire Prevention and Safety Grant Application 1–5 Preparing The Budget 1–7 Submitting Your Fire Prevention and Safety Application 1–8 Other Sources Of Grant Funding 1–9 Beyond The Basics 1–10 Grant Planning Guide 1–10 More Information 1–13 Resources 1–14 2 MARKETING AND COLLABORATING WITH SITES -

Smokey Bear Campfire Safety Checklist

Smokey Bear’s Guide Keep your campfire from becoming a wildfire! BEFORE … • Choose a spot that’s protected from wind gusts and at least 15 feet from your tent, gear, and anything flammable. • Clear a 10-foot diameter area around your campfire spot by removing leaves, grass, and anything burnable down to the dirt. • Don’t build your campfire near plants or under tree limbs or other flammable material hanging overhead. • If allowed, dig a pit for your campfire, about 1-foot deep, in the center of the cleared area. • Build a fire ring around the pit with rocks to create a barrier. • Don’t use any type of flammable liquid to start your fire. • Gather three types of wood to build your campfire and add them in this order: 1 2 3 Tinder – small twigs, dry Kindling – dry sticks Firewood – larger, dry pieces of leaves or grass, dry needles. smaller than 1” around. wood up to about 10” around. DURING … • Keep your fire small. • Always keep water and a shovel nearby and know how to use them to put out your campfire. • Be sure an adult is always watching the fire. • Keep an eye on the weather! Sudden wind gusts can blow sparks into vegetation outside your cleared area, causing unexpected fires. AFTER … REMEMBER: • If possible, allow your campfire to burn out completely – to ashes. If it’s too hot to • Drown the campfire ashes with lots of water. touch, it’s too • Use a shovel to stir the ashes and water into a “mud pie.” Be sure to scrape around the edges of the fire to get all the ashes mixed in. -

Samhain Quest Pack

Pagan Federation presents Aether Patches Samhain Quest This quest pack has been designed to help children understand more about the festival of Samhain, both its meaning and tra- ditions as well as some correspondences. Suggested challenge levels for different ages: Choose your challenges from across the 5 senses Amethyst (3-5 Years) : Complete a minimum of 3 challenges. Topaz (6-9 Years) : Complete a minimum of 5 challenges. Emerald (10-14 Years) : Complete a minimum of 7 challenges. Ruby (14-18 Years) : Complete a minimum of 10 challenges. Diamond (Over 18s) : Complete a minimum of 13 challenges or award yourself a badge for assisting young people in achieving the quest. Once completed feel free to award the certificate and patch from our website www.pfcommunity.org.uk Sight Challenges Sight challenges are often about looking up information and learning about something new, something relating to this quest. Sometimes they are just about using your eyes to see what you can see Samhain means ‘Summers end’ and is the time when nature starts winding down to rest. Look up and learn about different ways nature rests, such as hibernation. How do you take time to rest? Samhain is associated with Crone Goddesses. Look up and learn about these different deities, don’t forget to write them down in your journal. Samhain marks the end of summer and beginning of winter. Go for a walk in the woods or through a park and notice how the seasons are changing. Write it down in your journal. Samhain is a time to honour our ancestors. -

In the Autumn 2011 Edition of the Quiver I Wrote an Article Touching on the Topic of Survival As It Applies to the Bowhunter

In the Autumn 2011 edition of The Quiver I wrote an article touching on the topic of survival as it applies to the bowhunter. In this article I want to talk about fire specifically and the different types of firestarters and techniques available. Fire is an important element in a survival situation as it provides heat for warmth, drying clothes or cooking as well as a psychological boost and if you’re hunting in a spot where you are one of the prey species it can keep predators away as well. There are many ways to start a fire; some ways relatively easy and some that would only be used as a last resort. There are pros and cons to most of these techniques. The most obvious tool for starting a fire is a match. While this is a great way to start a fire in your fireplace or fire pit I personally don’t like to carry matches in my pack or on my person. They are hard to keep dry and you are limited to one fire per match IF you can light a one match fire every time. It would be easy to run out of matches in a hurry as you are limited in how many you could reasonably carry. A Bic lighter or one of the more expensive windproof lighters is a slightly better choice for the bowhunter to carry. They are easy to use, easy to carry, fairly compact, and last for a reasonable amount of “lights”. They don’t work well when wet but can be dried out fairly easily. -

FINAL REPORT Title: Multi-Scale Study of Ember Production and Transport Under Multiple Environmental and Fuel Conditions JFSP PROJECT ID:15-1-04-9

FINAL REPORT Title: Multi-Scale Study of Ember Production and Transport under Multiple Environmental and Fuel Conditions JFSP PROJECT ID:15-1-04-9 October 7, 2019 David L. Blunck, PhD Oregon State University Bret Butler, PhD US Forest Service John Bailey, PhD Oregon State University Natalie Wagenbrenner, PhD US Forest Service The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. - 1 - Table of Contents Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Overview and Objectives ................................................................................................... 6 2. Background ........................................................................................................................ 7 3. Materials and Methods ....................................................................................................... 9 4.1 Branch-scale Studies ........................................................................................................ 10 4.2 Tree-scale Studies ............................................................................................................ 12 4.2.1 Experimental Approach .......................................................................................... -

How to Build a Campfire

How to Build a Campfire GATHER BUILD tinder, kindling and fuel together in the sizes and the fire by adding kindling wood to the burning tinder quantities shown before any matches are struck. Sizes and then adding fuel to the fire as it grows. No need and quantities are just a ‘rule of thumb’ - get close to for a fancy fire lay, build it as you go. the descriptions and you’ll do fine. Don’t make any of it too short or too big around. Tinder from dead twigs found on Kindling should be dry, don’t gather Fuel should be dry, split larger wood the lower branches of trees and wet wood from the forest floor. Look if possible and have a good sized shrubs that snaps off easily when for branches that are dead and stack on hand before you light the bent. No green wood! down, not on the tree. fire. TINDER KINDLING FUEL Around the size of a No thicker than your About as thick as pencil lead thumb your wrist No shorter than your About as long as your About as long as your outstretched hand elbow to your arm fingertips Enough to fill a circle made with your Enough for a A stack about as high hands generous armload as your knee Bend the tinder in half and light 1 the center. Add kindling, keep piling it on loosely, give the fire plenty of 2 kindling to keep growing. As the kindling begins to burn 3 begin adding fuel. www.girlscoutshs.org • 800.624.4185. -

Protect Your Property from Wildfire Table of Contents

www.firesafemarin.org CALIFORNIA EDITION Protect Your Property from Wildfire Table of Contents 4 You Can Make a Difference • An Overview of this Guide: Reducing the Vulnerability of Your Home or Business • Managing Vegetation and Other Combustible Materials Around Your Home or Business ○ Defensible Space • Understanding Terms: The Role of Building Codes and Test Standards for Materials ○ California Building Code Chapter 7A Summary • Improving the Wildfire Resistance of Your Home or Business 9 Roof Covering • Things to Keep in Mind When Choosing a Class A Roof Covering • Tile and Other Roof Coverings with Gaps at the Edges • Skylights 12 Gutters 13 Vents: Under-Eave, Attic and Crawl Space (Foundation) 15 Windows and Doors 18 Decks, Patios and Porches 21 Siding 23 Fences 24 Chimneys, Burn Barrels and Open Debris Burning 25 Vegetative Fuels Treatments Away from Buildings 25 Creating Defensible Space • Identifying Fuels Management Zones • Defensible Space ○ Zone 1: 0-5 Feet (Near-Home Noncombustible Zone) ○ Zone 2: 5-30 Feet (Lean, Clean and Green Zone) ○ Zone 3: 30-100 Feet 30 Firewood, Leftover Materials and Combustible Materials 30 Plants 31 Yard and Garden Structures 32 Outbuildings, Fuel Tanks and Combustibles 33 Importance of Topography 34 Importance of Environmental Condition 34 Defensive Actions • If You are Trapped and Cannot Leave • External Water Spray System • Gel Coatings 37 Additional Resources for Vegetation/Plant Selections 4 PROTECT YOUR PROPERTY FROM WILDFIRE YOU CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE Research and post-fire assessments have shown that property owners can protect their homes and businesses against wildfire by addressing three clear sources of vulnerability: materials and design features used in building the home or business, the landscaping vegetation located immediately adjacent to the home or business, and the general vegetation and other combustible materials and items on the property surrounding the home or business. -

Fire Spread on Ember-Ignited Decks CONSTRUCTION

WILDFIRE RESEARCH FACT SHEET Fire Spread on Ember-Ignited Decks CONSTRUCTION Wind-blown embers generated during wildfires are the single biggest hazard wildfires pose to RECOMMENDATIONS homes, and homeowners should never overlook the potential risk that an attached deck can IBHS research shows that, for medium create. Recent testing by the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) offers density softwood decking products (such as redwood and cedar), which can be important findings that can help minimize risk from wind-blown embers to decks. vulnerable to ignition from embers, the associated fire spread on the deck can be Nothing that can ignite should be stored under a deck. This action, along with development minimized by the following: of effective and well-maintained home ignition zones, will minimize the chance of all but a wind- blown ember exposure to your deck. An ignited deck can result, for example, in the ignition of combustible siding, or glass breakage in a sliding glass door. Increase the gap between ABOUT THE RESEARCH TESTS regardless of the deck board’s orientation deck boards from 1/8 inch IBHS’s tests evaluated how an ember-ignited (parallel or perpendicular). When deck 1. to 1/4 inch. fire on an attached deck can spread to the boards were perpendicular to the building, home, and yielded important guidance to the fire would spread in the gap between Fire spread in the gap between deck boards. minimize the chance of fire spread to the boards. The 1/8” gap between deck boards Note the small flame burned all the way to house. -

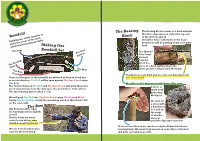

Bowdrill Block of the Drill Can Spin In

The Bearing The Bearing Block is made of a hard material that has a depression in it that the top end Bowdrill Block of the drill can spin in. It must be very comfortable in the hand Rubbing two sticks together to because we will be pushing down on it quite make fire is one of the mostMaking Our hard. quintessential bushcraft skills. Bowdrill Set The Bow In a Spruce/ The Coal Pine forest Catcher the best bearing block is a The Bearing piece of a dead sapling where the Block The Drill knots grow in a ring around the trunk. The Base Board The knots are very hard and we carve our depression into These are the parts of the bowdrill, we will look at them in detail but one of the knots. as an introduction: The Drill will be spun against The Base Board using The Bow. We lubricate the depression with Spruce/Pine resin. The friction between The Drill and The Base Board will grind them into A stone or wood dust and also heat the dust up to the point where it smoulders. shells work The smouldering dust is called a ‘coal’. as bearing blocks too. We will push The Drill into The Base Board using The Bearing Block. Finally The Coal Catcher holds the ground up wood so that doesn’t fall We look for on the cold earth. a stone with The Bow a depression Our Bow should be ridge in it and use (not springy) and be slightly the point curved. of another Shorter bows are much stone to easier to use but an arms grind the depression smooth. -

Annual Events in Japan Page 1 / 6

ANNUAL EVENTS IN JAPAN PAGE 1 / 6 Practical Travel Guide - 805 ANNUAL EVENTS IN JAPAN Japan is a land of many festivals. In cities, large and small, as well trip to Japan, you have an opportunity of enjoying a goodly num- as in rural districts, colorful rites and merrymaking—some of ber of these celebrations. And, joining the joyful throng, you will religious significance and others to honor historical personages actually feel the pages of Japanese history being turned back and or occasions—are held throughout the four seasons. will experience the pleasant thrill of peeking into the nation’s No matter what month of the year you may choose for your ancient culture and traditions. Date Event & Site Remarks JANUARY 1st New Year’s Day New Year’s Day, the “festival of the festivals” in Japan, is celebrated with solemnity (national holiday) and yet in a joyful mood. The streets are gay with New Year decorations of pine and plum branches, bamboo stalks and ropes with paper festoons. People pay hom- age to shrines and visit friends and relatives to exchange greetings. 3rd Tamaseseri or Ball-Catching The main attraction of this festival is a struggle between two groups of youths to Festival, Hakozakigu Shrine, catch a sacred wooden ball, which is believed to bring good luck to the winning Fukuoka City team for the year. 6th Dezome-shiki or New Year The parade takes place in Tokyo Big Sight. Agile firemen in traditional attire per- Parade of Firemen, Tokyo form acrobatic stunts on top of tall bamboo ladders.