Sharing Or Commoditising? a Discussion of Some of the Socio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

INTRODUCTION « Un personnage exceptionnel » Taamusi Qumaq est un personnage exceptionnel à plus d’un titre. Chasseur, pêcheur, trappeur, conducteur de chiens de traîneau, puis employé de la Compagnie de la Baie d’Hudson et des coopératives, président du conseil communautaire de Puvirnituq au Nunavik (Québec arctique) et homme politique, c’était également un encyclopédiste, un penseur et un activiste culturel de haut calibre. Sans oublier son rôle d’époux, de père de famille et de citoyen à l'écoute de son milieu, celui des Inuit1 du 20e siècle. Il a été récipiendaire de l’ordre du Québec et de celui du Canada, comme aussi du prix de la recherche nordique — décerné par le ministère canadien des Affaires indiennes et du Nord aux chercheurs émérites en études arctiques — et d’une mention honorable de l’Université du Québec, l’équivalent 1 On notera que les mots inuit apparaissant dans l’autobiographie, y compris les noms propres, sont écrits en orthographe standard du Nunavik. Cette graphie reflète la prononciation réelle de la langue. Seuls quelques noms de famille et prénoms modernes ont été transcrits dans leur orthographe courante, non standard. Par exemple, le prénom du père de Qumaq est écrit Nuvalinngaq (graphie standard), mais le nom de famille de son fils — le prénom du grand-père paternel, imposé comme nom de famille par les autorités fédérales au cours des années 1960 — est transcrit Novalinga. De même, pour respecter le génie de l’inuktitut et le sentiment de ses locuteurs, il a été décidé dès la première publication de l’autobiographie que le mot « inuit » resterait invariable en français, sans « e » au féminin ni « s » au pluriel. -

Cold Regions: Pivot Points, Focal Points

Cold Regions: Pivot Points, Focal Points Proceedings of the 24th Polar Libraries Colloquy June 11–14, 2012 Boulder, Colorado, United States edited by Shelly Sommer and Ann Windnagel colloquy organized by Gloria Hicks and Allaina Wallace, National Snow and Ice Data Center Shelly Sommer, Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research December 2012 Table of Contents Photo of participants .................................................................................................. 4 Opening and closing speakers ..................................................................................... 5 Keynote speaker: Dr. James W. C. White “Climate is changing faster and faster” ........................ 5 Closing speaker: Leilani Henry “We are all Antarctica” ............................................................................. 6 Session 1: Arctic higher education and library networks .............................................. 7 University of the Arctic Digital Library: Update 2012 ..................................................................................... 8 Sandy Campbell University of Lapland going to be really Arctic university – challenges for the library ..................... 15 Susanna Parikka Session 2: Best practices in collecting, searching, and using digital resources ............. 21 The network surrounding the Library of the National Institute of Polar Research (NIPR) .............. 22 Yoriko Hayakawa All you can get (?): Finding (full-text) information using a discovery service ..................................... -

Tourisme, Identité Et Développement En Milieu Inuit Le Cas De Puvirnituq Au Nunavik

52 TOURISME POLAIRE Tourisme, identité et développement en milieu inuit Le cas de Puvirnituq au Nunavik Véronique ANTOMARCHI 1 Docteure en histoire Professeur agrégée Chercheure associée au CERLOM-INALCO [email protected] RÉSUMÉ : Les enjeux de la mise en tourisme de la communauté de Puvirnituq au Nunavik posent des problèmes inhérents à la fois au tourisme polaire et au tourisme autochtone en termes de positionnement, voire de recomposition identitaire et de valorisation économique du territoire. La spécificité de Puvirnituq repose surtout sur l’importance de son patrimoine culturel, notamment son rôle pionnier dans la genèse du mouvement des coopératives avec la vente de sculptures à la fin des années 1950 ainsi que sa position résolument dissidente depuis la fin des années 1970. Les négociations qui ont cours en ce moment visant une autonomie du Nunavik en 2010 pourraient lui permettre de jouer un rôle administratif important, même si Kuujjuaq, l’autre grande communauté inuite du Nunavik, est pour l’heure pressentie pour devenir la capitale de cette nouvelle région. Mots-clés : Arctique, Canada, développement, identité, Inuit, Nunavik, Nord Québec, tourisme. Le Grand Nord, porteur d’un puissant imaginaire nourri de L’émergence du tourisme polaire a pris, à notre sens, une récits d’exploration, de témoignages ethnographiques et de dimension nouvelle au lendemain des attentats du 11 sep- documentaires, exerce une fascination qui remonte bien sou- tembre 2001 (Antomarchi, 2005 : 54). Répondant à des vent à l’enfance. Les représentations de paysages du Nord à la atouts de sécurité apparente face aux menaces terroristes et fois magnifiques et terrifiants, marqués par l’isolement, le froid, sanitaires, les territoires arctiques sont tous sous la houlette la menace de mort, se fixent dès le XIXe siècle avec l’irruption de de pays développés : États-Unis, Canada, Danemark, Russie, la notion de « sublime » qui recouvre trois aspects essentiels, l’es- Norvège, Suède, Finlande, Islande. -

Inuit Uqausillaringat, Taamusi Qumaq (1991), Inuksiutikkunullu Avatakkunullu Nuitartitait, 600 P

Document generated on 09/23/2021 6:22 a.m. Revue québécoise de linguistique Inuit Uqausillaringat, Taamusi Qumaq (1991), Inuksiutikkunullu Avatakkunullu Nuitartitait, 600 p. « Les véritables mots inuit », un dictionnaire de définitions en inuktitut du Québec arctique. Gilbert Taggart Les clitiques Volume 24, Number 1, 1995 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/603109ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/603109ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Université du Québec à Montréal ISSN 0710-0167 (print) 1705-4591 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Taggart, G. (1995). Review of [Inuit Uqausillaringat, Taamusi Qumaq (1991), Inuksiutikkunullu Avatakkunullu Nuitartitait, 600 p. « Les véritables mots inuit », un dictionnaire de définitions en inuktitut du Québec arctique.] Revue québécoise de linguistique, 24(1), 191–196. https://doi.org/10.7202/603109ar Tous droits réservés © Université du Québec à Montréal, 1995 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Revue québécoise de linguistique, vol. 24, n° 1, 1995, © RQL (UQAM), Montréal Reproduction interdite sans autorisation de l'éditeur INUIT UQAUSILLARINGAT Taamusi Qumaq (1991) Inuksiutikkunullu Avatakkunullu Nuitartitait, 600 pages "Les véritables mots inuit" un dictionnaire de définitions en inuktitut du Québec arctique Gilbert Taggart Université Concordia ET OUVRAGE de Taamusi Qumaq a été largement salué par la presse lors C de sa parution en 1991, mais peu commenté depuis, peut-être en raison de sa relative inaccessibilité au lecteur eurocanadien. -

The Social and Cultural Context of Inuit Literary History

Daniel Chartier Research Chair on Images of the North, Winter and the Arctic, Université du Québec à Montréal The Social and Cultural Context of Inuit Literary History Inuit literature already has a specifie place in world heritage, since it is seen as a 1 testimony of the possibility for man to live in the toughest conditions • Written Inuit literature is more particular: it develops at the end of the twentieth and the beginning of the twenty-first century, at a time when books and magazines are challenged by new media and new publication forms. It shares with other native artistic expressions a strong political meaning, considered either postcolonial or, as sorne suggest, not yet postcolonial. It also conveys rich oral and sculptural traditions, in its inventive new ways of making literature. However, as the few researchers on this literature point out, Inuit works received no or little critical attention, and they are almost never part of university curriculum (Kennedy). Ali these facts combine to form a fascinating case for research, which poses consider- able methodological challenges. Nunavik Inuit literature, which appears to be both part of a greater Inuit who le (including Nunavut, Greenland, Northwest Territories) and exclusive in its situa- tion - at the crossroads between Inuktitut, English and French languages - poses specifie challenges to the literary historian. The objective of this article is to examine sorne of the parameters within which we can think of a first historical interpretation of the evolution of written literature in Nunavik, the Inuit region of Québec, which, as of 1959, signais the beginning of a written self-representation of the Inuit. -

A Problem of the Government? Colonization and the Socio-Cultural

A Problem of the Government? Colonization and the Socio-Cultural Experience of Tuberculosis in Nunavut Masters Thesis Helle Møller Institute for Anthropology Copenhagen University April 21st, 2005 Table of Contents Acknowledgements i 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Genesis of the study 2 1.2 Research questions 2 1.3 Colonization and the meaning making of TB 3 1.4 A brief history of Arctic colonization 4 1.5 The field 5 1.6 Structure of the thesis 7 2. Methodology 8 2.1 Whose story is it anyway? Positioning the researcher 8 2.2 Interviews and illness stories 10 2.2.1 Illness narratives, which leave the meaning making to the audience 10 2.2.2 Interviews as a tool for making meaning rather than reaching goals 14 2.2.3 When both interviewer and interviewee speak English as a second 16 language 2.2.4 Other Stories 18 2.3 Participation in community life 19 2.4 Participants 20 3. The why and how of TB, health and disease 21 3.1 The Aetiology of TB from a biomedical point of view 22 3.2 Containment, surveillance and treatment of TB today 23 3.3 Ways of knowing, knowledge production, and knowledge display 25 3.3.1 Displaying knowledge 26 3.3.2 Creating Knowledge 29 3.4 The experience and meaning making of health, illness, disease and cure 32 among Inuit 3.4.1 Good health allows Inuit to do whatever they want 33 3.4.2 Being sick and getting well 34 3.4.3 Identity and health 37 3.5 Correct interactions…with people, animals, community and environment 39 3.5.1 How people get sick and why exactly they do 39 3.5.2 The impact of proper social conduct 43 3.5.3 Respect, independence and identity 44 4. -

La Fascinante Émergence Des Littératures Inuite Et Innue Au 21E Siècle Au Québec : Une Réinterprétation Méthodologique Du Fait Littéraire Daniel Chartier

La fascinante émergence des littératures inuite et innue au 21e siècle au Québec : Une réinterprétation méthodologique du fait littéraire Daniel Chartier To cite this version: Daniel Chartier. La fascinante émergence des littératures inuite et innue au 21e siècle au Québec : Une réinterprétation méthodologique du fait littéraire. Revue japonaise d’études québécoises, 2019, pp.27-48. hal-02561455 HAL Id: hal-02561455 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02561455 Submitted on 3 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright 【特別寄稿】 La fascinante émergence des littératures inuite et innue au 21e siècle au Québec : Une réinterprétation méthodologique du fait littéraire 21 世紀ケベックにおけるイヌイットおよびイヌー文学の 魅惑的出現:文学的事実の方法論的再解釈 Daniel CHARTIER ダニエル・シャルティエ 要約 世界各地、とくに北方で、先住民たちによって書かれた文学が出現した ことは 21 世紀初頭の特徴となっている。ケベック州にとっては、イヌーとイ ヌイットの文学的事例を研究することによって、この現象が歴史的かつ方法 論的にどのような重要な問題を提起しているか知ることができるし、同時に、 これら 2 つの文学が互いに大きく異なるものであることも知ることができる。 イヌー文学はケベック文学に近く、文学上の諸機関も共通しているのにたい して、イヌイット文学のほうは北極を取り巻くものの一部を成しており、距 離を保っている。文学の機能と利用法(証言、治癒、知識の伝達)、認識の方 法としての語りの重要性、そして自然との親密な関係といったものが 2 つの 文学をともに特徴づけている。ジョゼフィーヌ・バコン、ナオミ・フォンテー ヌ、タームシ・クマック、マリー=アンドレ・ジルの諸作品は、長いあいだ 過小評価されてきたファースト・ネイションズやイヌイットたちの世界を読 者たちに発見させてくれる。彼らの作品が今日国際的に成功していることは、 人々がそれらに向ける批評的関心の高さを裏づけている。 Mots clés : Québec, Littérature, Premières Nations, Inuits, Autochtones キーワード:ケベック、文学、ファースト・ネイションズ、イヌイット、先 住民 27 La mise en valeur des littératures autochtones au Québec En principe, en langue française est « autochtone » celui ou celle qui est originaire du lieu où il ou elle vit encore. -

Numéro Spécial, Entretiens Sur L'habitat, Automne 2013

SOCIÉTÉ HABITATION D’HABITATION DU QUÉBEC QUÉBEC LE BULLETIN D’INFORMATION DE NUMÉRO SPÉCIAL LA SOCIÉTÉ D’HABITATION DU QUÉBEC ENTRETIENS SUR L’HABITAT, AUTOMNE 2013 LE LOGEMENT DANS LE GRAND-NORD Le Grand-Nord québécois fait partie de l’imaginaire québécois. Il évoque les grands espaces vierges, le froid et la neige, et une population qui a entrepris sa sédentarisation il y a trois quarts de siècle, avec de fortes traditions mais aussi d’importantes ressources naturelles. Depuis quelques années, les annonces pour développer le Nord soulèvent des questions parmi la population du Grand-Nord. Cette dernière demande une exploitation des ressources nordiques dans le respect de leurs com- munautés à titre de parties prenantes dans les décisions et chantiers à venir, tout ça dans la philosophie de la Convention de la Baie-James et du Nord québécois, signée en 1975. Ce numéro spécial du bulletin Habitation Québec met la table pour les Entretiens sur l’habitat, que la Société d’habitation du Québec tiendra le mardi 8 octobre 2013, à Québec, sur le thème : « Le logement dans le Grand-Nord québécois ». Dans le texte qui suit, il sera question du Nunavik et des conditions d’habitation de sa population, puisque les interventions du gouvernement du Québec en matière de logement dans le Grand-Nord ciblent uniquement ce territoire nordique1. En guise de contexte, nous décrirons brièvement le territoire du Nunavik et ses principales caractéristiques, pour présenter ensuite ses habitants, à 89 % inuits, puis quelques particularités historiques et culturelles, notamment quant à l’occupation du territoire et à la manière d’habiter. -

Language, Culture and Identity: Some Inuit Examples

LANGUAGE, CULTURE AND IDENTITY: SOME INUIT EXAMPLES Louis-Jacques Dorais Département d'anthropologie Université Laval Québec, Québec Canada, G1K 7P4 Abstract / Resume The author outlines differences between cultural and ethnic identity among Canadian Inuit and assesses the relative importance of language (with special emphasis on Native language education) in defining these identi- ties. Data are drawn principally from interviews conducted with Igloolik (Nunavut) and Quaqtaq (Nunavik) Inuit in 1990-1991. The research sug- gests that cultural identity and ethnic identity are indeed different, and that language, without being essential to the definition of Inuit identity, never- theless plays a crucial role within contemporary Inuit culture. Cet article essaie de mettre en lumière la différence entre identités cul- turelle et ethnique chez les Inuit canadiens, et de mesurer l'importance relative de la langue (en mettant l'emphase sur l'éducation en langue autochtone) dans la définition de ces identités. Les données sont princi- palement tirées d'entrevues menées avec des Inuit d'Igloolik (Nunavut) et de Quaqtaq (Nunavik) en 1990-1991. La conclusion montre qu'identité culturelle et identité ethnique sont réellement différentes, et que la langue, sans être essentielle à la définition de l'identité inuit, n'en joue pas moins un rôle crucial dans la culture inuit contemporaine. 294 Louis-Jacques Dorais Introduction Over the last two decades, relationships among language, culture and identity have become a favourite topic in social science. Questions that keep popping up concern, for example, the difference between cultural and ethnic identity (cf. Abou, 1986; Lipianski et al., 1990; Eriksen, 1993; Meintel, 1993; Dorais, 1994). -

Traditional Inuit Stories by Noel K. Mcdermott a Thesis

Unikkaaqtuat: Traditional Inuit Stories By Noel K. McDermott A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Cultural Studies in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada April, 2015 Copyright © Noel McDermott, 2015 Abstract Commentary on Inuit language, culture and traditions, has a long history, stretching at least as far back as 1576 when Martin Frobisher encountered Inuit on the southern shores of Baffin Island. The overwhelming majority of this vast collection of observations has been made by non-Inuit, many of whom spent limited time getting acquainted with the customs and history of their objects of study. It is not surprising, therefore, that the lack of Inuit voice in all this literature, raises serious questions about the credibility of the descriptions and the validity of the information. The Unikkaaqtuat: Traditional Inuit Stories project is presented in complete opposition to this trend and endeavours to foreground the stories, opinions and beliefs of Inuit, as told by them. The unikkaaqtuat were recorded and translated by professional Inuit translators over a five day period before an audience of Inuit students at Nunavut Arctic College, Iqaluit, Nunavut in October 2001. Eight Inuit elders from five different Nunavut communities told stories, discussed possible meanings and offered reflections on a broad range of Inuit customs and beliefs. What emerges, therefore, is not only a collection of stories, but also, a substantial body of knowledge about Inuit by Inuit, without the intervention of other voices. Editorial commentary is intentionally confined to correction of spellings and redundant repetitions. -

INTERVIEWING INUIT ELDERS Perspectives on Traditional Health

6507_2EngCoverspine_bleed2.qxd 5/1/06 10:41 AM Page 1 INTERVIEWINGPerspectives INUIT onELDERS Traditional Health erspectives on Traditional Health P INTERVIEWING INUIT ELDERS Ilisapi Ootoova, Tipuula Qaapik Atagutsiak, Tirisi Ijjangiaq, Jaikku Pitseolak, Aalasi Joamie, Akisu Joamie, Malaija Papatsie 5 Edited by Michèle Therrien and Frédéric Laugrand 6507.5_Fre 5/1/06 9:11 AM Page 239 6507_2EnglishVol_5.qxd 5/1/06 10:22 AM Page 1 INTERVIEWING INUIT ELDERS Volume 5 Perspectives on Traditional Health Ilisapi Ootoova, Tipuula Qaapik Atagutsiak, Tirisi Ijjangiaq, Jaikku Pitseolak, Aalasi Joamie, Akisu Joamie, Malaija Papatsie Edited by Michèle Therrien and Frédéric Laugrand 6507_2EnglishVol_5.qxd 5/1/06 10:22 AM Page 2 Interviewing Inuit Elders Volume 5 Perspectives on Traditional Health Copyright © 2001 Nunavut Arctic College, and Ilisapi Ootoova, Tipuula Qaapik Atagutsiak, Tirisi Ijjangiaq, Jaikku Pitseolak, Aalasi Joamie, Akisu Joamie, Malaija Papatsie, Michèle Therrien, Frédéric Laugrand and participating students (as listed within). Photos courtesy: Dr. Andrus Voitk; Dr. Susan Aiken and Dr. Kathy Conlan, Canadian Museum of Nature; Dr. Scott Redhead, Agriculture Canada; and Jane Tagak. Cover illustration “Man and Animals” by Lydia Japoody. Design and production by Nortext (Iqaluit). All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without written consent of the publisher is an infringement -

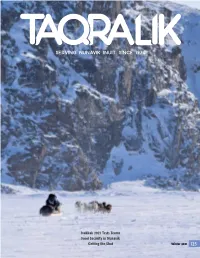

Issue 125-2021

SERVING NUNAVIK INUIT SINCE 1974 Ivakkak 2021 Tests Teams Food Security in Nunavik Getting the Shot Winter 2021 125 Makivik Corporation Makivik is the ethnic organization mandated to represent and promote the interests of Nunavik. Its membership is composed of the Inuit beneficiaries of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA). Makivik’s responsibility is to ensure the proper implementation of the political, social, and cultural benefits of the Agreement, and to manage and invest the monetary compensation so as to enable the Inuit to become an integral part of the Northern economy. Taqralik Taqralik is published by Makivik Corporation and distributed free of charge to Inuit beneficiaries of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. The opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of Makivik Corporation or its Executive. We welcome letters to the editor and submissions of articles, artwork or photographs. Email [email protected] or call 1-800-361-7052 for submissions or for more information. Makivik Corporation Executives Pita Aatami, President Maggie Emudluk, Vice President, Economic Development Adamie Delisle Alaku, Vice President, Environment, Wildlife and Research George Berthe, Treasurer Rita Novalinga, Corporate Secretary We wish to express our sincere thanks to all Makivik staff, as well as to all others who provided assistance and materials to make the production of this magazine possible. Director of Communications Carson Tagoona Editor Miriam Dewar Translation/Proofreading Minnie Amidlak Sarah Aloupa Eva Aloupa-Pilurtuut Alasie Kenuajuak Hickey CONTENTS Published by Makivik Corporation P.O. Box 179, Kuujjuaq (QC) J0M 1C0 Canada Telephone: 819-964-2925 *Contest participation in this magazine is limited to Inuit beneficiaries of the JBNQA.