Why Are Civil Partnerships Such a Divisive Issue in Italian Politics?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programma Politico

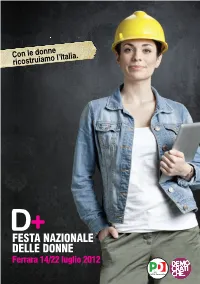

A L WC BO OM T PALCO TOMBOLA CUCINA RISTORANTE BAR O SPAZIO ASSOCIAZIONI O FEMMINILI DOLCIUMI SS E E SPAZIO SPAZIO O DIBATTITI T N N I I I E PESCA T A CONDARI N NGR R I PAPERETTE SC E O I O LIBRERIA DONNE E GE S R P A RIST AZI P O BIMB I E S ANO T T E PESCA N GONFIABIL GG A PREMI E R A O ESC MOSTRE G CHE P LISTONE DONN A R RIST LUDOTECA A VI P A BAR RE BAR A GELATERIA PALCO PINZINI SPETTACOLI LIBRERIA AREA ARENA SPAZIO ESPOSITORI BALLO DIBATTITI Programma politico sabato Corsa per la lotta ai tumori del seno. 14 Ritrovo Giardino delle Duchesse ore 8.00 Riscaldamento: ore 8.30 Giardino delle duchese ore 9.00 Ore 8:00 Partenza: Ore 19:00 Inaugurazione Festa Nazionale delle Donne Paolo Calvano (Segretario Provinciale Pd Ferrara) Caterina Palmonari (Coordinatrice Provinciale Conferenza Donne Ferrara) Lucia Bongarzone (Coordinatrice Regionale Conferenza Donne E-R) Roberta Agostini (Coordinatrice Nazionale Conferenza Donne Pd) SPAZIO DIBATTITI Ore 21:00 “Donne che non hanno paura” Patrizia Moretti, Ilaria Cucchi, Donata Bergamini, Lucia Uva, Domenica Ferulli, Sen. Teresa Bertuzzi e Filippo Vendemmiati (Giornalista e autore del film “E’ stato morto un ragazzo”) domenica 15 Presentazione libro-inchiesta di Chiara Valentini "O i figli o il lavoro" Modà Partecipano: Chiara Valentini, Anna Rea (Segretaria confederale Uil), Sen. Rita Ghedini, Via della Luna 30 (Portavoce Nazionale Tilt). Coordina (Conf. Donne PD) Ore 18:30 Maria Pia Pizzolante Federica Mariotti Accompagnamento musicale “Francesco Minotti” SPAZIO DIBATTITI Spettacolo Teatrale Donne Comunitarie Pontelagoscuro Ore 20:45 -Asylum Il manicomio delle Attrici- regia Cora Herrendorf “Violenza sulle donne: Insieme possiamo dire basta” Partecipano On. -

Marxism and Bourgeois Democracy. Reflections on a Debate After the Second World War in Italy

53 WSCHODNI ROCZNIK HUMANISTYCZNY TOM XVI (2019), No 1 s. 53-65 doi: 10.36121/dstasi.16.2019.1.053 Daniele Stasi (University of Rzeszów, University of Foggia) ORCID 0000-0002-4730-5958 Marxism and bourgeois democracy. Reflections on a debate after the Second World War in Italy Annotation: In this paper is illustrated a debate about the form of State and democracy be- tween N.Bobbio, some Italian Marxist philosophers and intellectuals. The debate took place in 1970s, that is in a period of intense philosophical confrontation, hosted by cultural reviews like „Mondoperaio” and marked by a strong ideological opposition linked to the world bipo- lar system. The paper presents the general lines of that debate, which highlighted the inad- equacies of the Marxist doctrine of State, consistently determining the end of any hegemonic ambitions in the Italian culture of those intellectuals linked to international communism. Keywords: Marxism, democracy, State, Italian philosophy, hegemony, Norberto Bobbio. Marksizm i burżuazyjna demokracja. Refleksje na temat debaty po drugiej wojnie świa- towej we Włoszech Streszczenie: W artykule przedstawiono debatę o kształcie państwa i demokracji, która toczyła się pomiędzy N. Bobbio i niektórymi marksistowskimi filozofami włoskimi w la- tach siedemdziesiątych XX wieku. Okres ten cechuje intensywna konfrontacja filozoficznа we Włoszech związana z sytuacją polityczną na świecie. Debata miała miejsce na łamach czasopisma „Mondoperaio”. W artykule zostały zilustrowane podstawowe tezy owej deba- ty, które podkreślają niedostatki marksistowskiej doktryny o państwie, konsekwentnie wy- znaczając koniec wszelkich hegemonicznych ambicji włoskich intelektualistów związanych z międzynarodowym komunizmem. Słowa kluczowe: marksizm, demokracja, państwo, filozofia włoska, hegemonia, Norberto Bobbio. Марксизм и буржуазная демократия. -

Eletti Naz Provv X Stampa

Pd, i 398 eletti lombardi all'Assemblea Costituente nazionale Lombardia1 Collegio Nome Lista Nome e Cognome Candidato 1 Milano Con Veltroni. ambiente, lavoro, innovazione, sinistra. Emilia Moratti Bossi detta Milly 1 Con Veltroni. ambiente, lavoro, innovazione, sinistra. Severino Salvemini 1 Con Veltroni. ambiente, lavoro, innovazione, sinistra. 1 Milano Democratici lombardi per Veltroni Barbara Pollastrini 1 Democratici lombardi per Veltroni Vittorio Gregotti 1 Democratici lombardi per Veltroni 1 Milano I democratici per Enrico Letta Ferdinando Targetti 1 I democratici per Enrico Letta 1 Milano con Rosy Bindi democratici, davvero. Gad Lerner 1 con Rosy Bindi democratici, davvero. Bruna Mekbuli 1 con Rosy Bindi democratici, davvero. 2 Milano Con Veltroni. ambiente, lavoro, innovazione, sinistra. Teresa Cardona 2 Con Veltroni. ambiente, lavoro, innovazione, sinistra. Giorgio Roilo 2 Con Veltroni. ambiente, lavoro, innovazione, sinistra. 2 Milano Democratici lombardi per Veltroni Eva Cantarella 2 Democratici lombardi per Veltroni Alberto Mattioli 2 Democratici lombardi per Veltroni 2 Milano I democratici per Enrico Letta Giuseppina Rosco 2 I democratici per Enrico Letta 2 Milano con Rosy Bindi democratici, davvero. Sabina Ratti 2 con Rosy Bindi democratici, davvero. Francesco Totaro 2 con Rosy Bindi democratici, davvero. 3 Milano Con Veltroni. ambiente, lavoro, innovazione, sinistra. Stefano Boeri 3 Con Veltroni. ambiente, lavoro, innovazione, sinistra. Alessandra Bassan detta Sandra 3 Con Veltroni. ambiente, lavoro, innovazione, sinistra. 3 Milano Democratici lombardi per Veltroni Linda Lanzillotta 3 Democratici lombardi per Veltroni Alberto Martinelli 3 Democratici lombardi per Veltroni 3 Milano I democratici per Enrico Letta Giacomo Vaciago 3 I democratici per Enrico Letta 3 Milano con Rosy Bindi democratici, davvero. Roberto Zaccaria 3 con Rosy Bindi democratici, davvero. -

Governo Berlusconi Iv Ministri E Sottosegretari Di

GOVERNO BERLUSCONI IV MINISTRI E SOTTOSEGRETARI DI STATO MINISTRI CON PORTAFOGLIO Franco Frattini, ministero degli Affari Esteri Roberto Maroni, ministero dell’Interno Angelino Alfano, ministero della Giustizia Giulio Tremonti, ministero dell’Economia e Finanze Claudio Scajola, ministero dello Sviluppo Economico Mariastella Gelmini, ministero dell’Istruzione Università e Ricerca Maurizio Sacconi, ministero del Lavoro, Salute e Politiche sociali Ignazio La Russa, ministero della Difesa; Luca Zaia, ministero delle Politiche Agricole, e Forestali Stefania Prestigiacomo, ministero dell’Ambiente, Tutela Territorio e Mare Altero Matteoli, ministero delle Infrastrutture e Trasporti Sandro Bondi, ministero dei Beni e Attività Culturali MINISTRI SENZA PORTAFOGLIO Raffaele Fitto, ministro per i Rapporti con le Regioni Gianfranco Rotondi, ministro per l’Attuazione del Programma Renato Brunetta, ministro per la Pubblica amministrazione e l'Innovazione Mara Carfagna, ministro per le Pari opportunità Andrea Ronchi, ministro per le Politiche Comunitarie Elio Vito, ministro per i Rapporti con il Parlamento Umberto Bossi, ministro per le Riforme per il Federalismo Giorgia Meloni, ministro per le Politiche per i Giovani Roberto Calderoli, ministro per la Semplificazione Normativa SOTTOSEGRETARI DI STATO Gianni Letta, sottosegretario di Stato alla Presidenza del Consiglio dei ministri, con le funzioni di segretario del Consiglio medesimo PRESIDENZA DEL CONSIGLIO DEI MINISTRI Maurizio Balocchi, Semplificazione normativa Paolo Bonaiuti, Editoria Michela Vittoria -

M Franchi Thesis for Library

The London School of Economics and Political Science Mediated tensions: Italian newspapers and the legal recognition of de facto unions Marina Franchi A thesis submitted to the Gender Institute of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, May 2015 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 88924 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help (if applicable) I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Hilary Wright 2 Abstract The recognition of rights to couples outside the institution of marriage has been, and still is, a contentious issue in Italian Politics. Normative notions of family and kinship perpetuate the exclusion of those who do not conform to the heterosexual norm. At the same time the increased visibility of kinship arrangements that evade the heterosexual script and their claims for legal recognition, expose the fragility and the constructedness of heteronorms. During the Prodi II Government (2006-2008) the possibility of a law recognising legal status to de facto unions stirred a major controversy in which the conservative political forces and the Catholic hierarchies opposed any form of recognition, with particular acrimony shown toward same sex couples. -

Giusta Direzione

L’idea dell’Europa forse era e rimane un’utopia. Ma è stata e rimane una utopia attiva. E la sua attività dipenderà dai suoi attori Zygmunt Bauman 1,30 Anno 91 n. 98 Giovedì 10 Aprile 2014 Russell Crowe: «Il web del futuro Il fascino quel gladiatore discreto sull’Arca di Noé sarà meno social del design U: Crespi pag. 20 Intervista a David Shing - Buquicchio pag. 17 Pivetta pag. 19 Un bel giorno per le donne Fecondazione, Capolista del Pd adesso si cambia tutte al femminile Incostituzionale: la Corte Costituzionale boccia il divieto di Il Pd mette alla guida delle liste per le elezioni europee cin- fecondazione eterologa previsto dalla legge 40 del 2004 che que donne. La svolta matura nella notte di martedì, quando nega la possibilità di ricorrere alla donazione di gameti (ovo- Renzi decide di dare un segnale forte e compiere una scelta citi o spermatozoi) esterni alla coppia. Cade, dunque, un che nessuno aveva mai fatto. Alessandra Moretti nel Nor- tabù. L’Italia cambia. La sentenza ha effetti immediati: in dest, Alessia Mosca nel Nordovest, Simona Bonafè al Cen- alcuni centri privati sarà già possibile intervenire, mentre tro, Pina Picierno al Sud e Caterina Chinnici nelle isole, so- nel pubblico ci vorrà più tempo. Intervista a Barbara Polla- no le capolista democratiche. Sì definitivo della Camera alla strini: ora serve una nuova legge, il governo la appoggi. legge sul riequilibrio di genere alle elezioni europee. COMASCHI GERINA A PAG. 8-9 GONNELLI FRULLETTI MARCUCCI A PAG. 2-3 Una scelta di buonsenso Un forte atto di rottura CARLO FLAMIGNI VALERIA VIGANÒ CREDO CHE LA COSA PIÙ IMPORTANTE ACCADUTA IN EURO- LA DECISIONE È STATA PRESA. -

Challenger Party List

Appendix List of Challenger Parties Operationalization of Challenger Parties A party is considered a challenger party if in any given year it has not been a member of a central government after 1930. A party is considered a dominant party if in any given year it has been part of a central government after 1930. Only parties with ministers in cabinet are considered to be members of a central government. A party ceases to be a challenger party once it enters central government (in the election immediately preceding entry into office, it is classified as a challenger party). Participation in a national war/crisis cabinets and national unity governments (e.g., Communists in France’s provisional government) does not in itself qualify a party as a dominant party. A dominant party will continue to be considered a dominant party after merging with a challenger party, but a party will be considered a challenger party if it splits from a dominant party. Using this definition, the following parties were challenger parties in Western Europe in the period under investigation (1950–2017). The parties that became dominant parties during the period are indicated with an asterisk. Last election in dataset Country Party Party name (as abbreviation challenger party) Austria ALÖ Alternative List Austria 1983 DU The Independents—Lugner’s List 1999 FPÖ Freedom Party of Austria 1983 * Fritz The Citizens’ Forum Austria 2008 Grüne The Greens—The Green Alternative 2017 LiF Liberal Forum 2008 Martin Hans-Peter Martin’s List 2006 Nein No—Citizens’ Initiative against -

Early Modern Conceptions of Property. Ed. by John Brewer and Susan Staves

International Review of Social History 43 (1998), pp. 287–314 1998 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis BOOK REVIEWS Early Modern Conceptions of Property. Ed. by John Brewer and Susan Staves. [Consumption and culture in 17th and 18th centuries, 2.] Routledge, London [etc.] 1995. xiv, 599 pp. Ill. Maps. £80.00. CARRIER,JAMES G. Gifts and Commodities. Exchange and Western Capital- ism since 1700. [Material Cultures.] Routledge, London [etc.] 1995. xvi, 240 pp. £45.00. In 1982 Neil McKendrick, John Brewer and J.H. Plumb helped to open up a new area of social and cultural history by publishing The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth-Century England (London, Europa). There had been earlier studies, but in economic history consumption had clearly caught the imagination less than production. Social historians had focused on the living standards of those who were supposed barely able to survive. But mass production at one end of the economy presupposes mass consumption at least somewhere else, in a domestic or foreign market, among workers or other classes.1 Production was in fact the vantage point of much early research in the history of consumption. The range and quality of goods produced gave at least some information about the buying public. As the title of the seminal work by McKendrick, Brewer and Plumb indicates, one of the questions which prompted the history of consumption is how (and when) mass consumption originated. Once, long ago, goods were typically produced for known customers, on demand and to their specifications, as single items or in small quantities, by workers they knew personally. -

Hegemonic Regulations of Kinship: Gender and Sexualities Norms in Italy

School of Social Sciences Department of Social and Organizational Psychology Hegemonic regulations of kinship: Gender and sexualities norms in Italy. Diego Lasio Thesis specially presented for the fulfillment of the degree of Doctor in Psychology Supervisor: João Manuel de Oliveira, PhD, Invited Assistant Professor ISCTE-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa December, 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to the University of Cagliari and the Department of Pedagogy, Psychology, Philosophy for allowing me to dedicate my time to fulfil this research project. To my colleagues and the administrative staff of this University for supporting me in many ways. I would like to thank the Doctoral Programme in Psychology of ISCTE-IUL for welcoming me to develop my research. Thanks to all the teachers, researchers and the attendants of the PhD Programme for their help and insights. A special thanks to all the administrative staff of the ISCTE-IUL, their support desk, and of the Centro de Investigação e Intervenção Social (CIS-IUL) for their kind assistance. This project would not have been possible without the encouragement, constant support and recognition of my supervisor Professor João Manuel de Oliveira. Thanks also for the future projects together. I am indebted to Professor Lígia Amâncio for her insightful and attentive feedback. It has been a privilege to cross paths with her. Francisco, Francesco and Emanuela were again invaluable. Thank you for the security and love that you offer me. ABSTRACT After many years of heated debate, in 2016 the Italian parliament passed a law to regulate same-sex civil unions. Although the law extends to same-sex couples most of the rights of married heterosexual couples, the law preserves legal differences between heterosexual marriage and same-sex civil unions; moreover, the possibility of a partner in a same-sex couple adopting the biological children of the other partner was so controversial that it had to be deleted in order for the law to pass. -

Resoconto Seduta N

XVIII LEGISLATURA Assemblea RESOCONTO STENOGRAFICO ALLEGATI ASSEMBLEA 328ª seduta pubblica mercoledì 19 maggio 2021 Presidenza del vice presidente La Russa, indi del vice presidente Taverna, del presidente Alberti Casellati, del vice presidente Calderoli e del vice presidente Rossomando Senato della Repubblica – 2 – XVIII LEGISLATURA 328ª Seduta ASSEMBLEA - INDICE 19 Maggio 2021 I N D I C E G E N E R A L E RESOCONTO STENOGRAFICO ........................................................ 5 ALLEGATO B (contiene i testi eventualmente consegnati alla Presi- denza dagli oratori, i prospetti delle votazioni qualificate, le comunica- zioni all’Assemblea non lette in Aula e gli atti di indirizzo e di controllo) ......................................................................................................... 103 Senato della Repubblica – 3 – XVIII LEGISLATURA 328ª Seduta ASSEMBLEA - INDICE 19 Maggio 2021 I N D I C E ROSSOMANDO (PD)................................................. ...22 RESOCONTO STENOGRAFICO GRASSO (Misto-LeU-Eco)....................................... ...23 SULL'ORDINE DEI LAVORI RICCARDI (L-SP-PSd'Az) .................................. ...23, 24 PAROLI (FIBP-UDC) .............................................. ...25 PRESIDENTE ............................................................... ...5 D'ANGELO (M5S) .................................................... ...26 DOCUMENTI CRUCIOLI (Misto) .................................................... ...27 PARAGONE (Misto) .................................................. ...27 -

What's Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging

What’s Left of the Left What’s Left of the Left Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times Edited by James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Duke University Press Durham and London 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: The New World of the Center-Left 1 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Part I: Ideas, Projects, and Electoral Realities Social Democracy’s Past and Potential Future 29 Sheri Berman Historical Decline or Change of Scale? 50 The Electoral Dynamics of European Social Democratic Parties, 1950–2009 Gerassimos Moschonas Part II: Varieties of Social Democracy and Liberalism Once Again a Model: 89 Nordic Social Democracy in a Globalized World Jonas Pontusson Embracing Markets, Bonding with America, Trying to Do Good: 116 The Ironies of New Labour James Cronin Reluctantly Center- Left? 141 The French Case Arthur Goldhammer and George Ross The Evolving Democratic Coalition: 162 Prospects and Problems Ruy Teixeira Party Politics and the American Welfare State 188 Christopher Howard Grappling with Globalization: 210 The Democratic Party’s Struggles over International Market Integration James Shoch Part III: New Risks, New Challenges, New Possibilities European Center- Left Parties and New Social Risks: 241 Facing Up to New Policy Challenges Jane Jenson Immigration and the European Left 265 Sofía A. Pérez The Central and Eastern European Left: 290 A Political Family under Construction Jean- Michel De Waele and Sorina Soare European Center- Lefts and the Mazes of European Integration 319 George Ross Conclusion: Progressive Politics in Tough Times 343 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Bibliography 363 About the Contributors 395 Index 399 Acknowledgments The editors of this book have a long and interconnected history, and the book itself has been long in the making. -

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta Sociálních Studií Katedra Politologie

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sociálních studií Katedra politologie DISERTAČNÍ PRÁCE Brno 2009 Tomáš Foltýn MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sociálních studií Katedra politologie Tomáš Foltýn Utváření stranického systému v podmínkách transformace politického systému. Italský stranický systém v letech 1994 - 2008. Disertační práce Školitel: prof. PhDr. Maxmilián Strmiska, Ph.D. Brno 2009 2 Prohlašuji tímto, že jsem předkládanou práci vypracoval samostatně toliko na základě pramenů uvedených v seznamu literatury. Tomáš Foltýn 3 Je mou milou povinností poděkovat na tomto místě svému školiteli, prof. Strmiskovi, nejen za řadu inspirativních a cenných poznámek, kterých mi k popisované materii během studia poskytl, ale v prvé řadě za jedinečný a neokázalý způsob, kterým se dělí o své hluboké znalosti (nejen ve vztahu ke zkoumanému tématu), díky čemuž je člověk nucen předkládat danou práci s nejvyšší možnou pokorou. Současně bych rád poděkoval svému nejbližšímu okolí, bez jehož tolerantního, chápavého, vstřícného a často i nápomocného přístupu by nebylo možné následující text vůbec dokončit. 4 Rekapitulace namísto úvodu ........................................................................................................ 7 2. Konceptualizace pojmu „druhá republika“ I. – perspektiva druhé poloviny devadesátých let .................................................................................................................................................... 12 2.1 Tranzice sui generis ........................................................................................................