Research by Design and GIS-Based Scenario Modelling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ganshoren Tussen Stad En Natuur

tussen stad Collectie Brussel, Stad van Kunst en Geschiedenis Ganshoren en natuur BRUSSELS HOOFDSTEDELIJK GEWEST 52 De collectie Brussel, Stad van Kunst en Ge- schiedenis wordt uitgegeven om het culturele erfgoed van Brussel ruimere bekendheid te geven. Vol anekdotes, onuitgegeven documenten, oude afbeeldingen, historische gegevens met bijzondere aandacht voor stedenbouw en architectuur vormt deze reeks een echte goudmijn voor de lezer en wandelaar die Brussel beter wil leren kennen. Ganshoren : tussen stad en natuur Het architecturaal erfgoed van de gemeente Ganshoren is gekenmerkt door een opvallende diversiteit. Hieruit blijkt duidelijk hoe sinds het einde van de 19de eeuw op het vlak van ruim- telijke ordening inspanningen zijn geleverd om in deze gemeente van het Brussels Gewest het evenwicht te behouden tussen stad en natuur. Het huidige Ganshoren is het resultaat van opeenvol- gende stedenbouwkundige visies. Dit boek vertelt het verhaal hierachter en neemt de lezer mee op een reis doorheen de boeiende geschiedenis van de Brusselse architectuur en stedenbouw. Charles Picqué, Minister-President van de Regering van het Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest belast met Monumenten en Landschappen Stedenboukundige verkenning van een gemeente Ondanks het aparte karakter en de diversiteit van de architectuur op zijn grondgebied blijft de gemeente Ganshoren slecht gekend . Dat is gedeeltelijk te verklaren door zijn perifere ligging . Maar naast die relatieve afgele- genheid is het waarschijnlijk de afstand tussen enerzijds het beeld dat men doorgaans heeft van een stad en anderzijds het feitelijke uitzicht van Ganshoren dat voor verwarring zorgt . Zijn contrastrijke landschap, dat aarzelt tussen stad en platteland, is niet gemakkelijk te vatten . We treffen er zeer duidelijke, zelfs monotone sequenties aan zoals de Keizer Karellaan of de woontorens langs de Van Overbekelaan . -

You Drive, We Care

You drive, we care. BE - Diesel & Services Belgien / Belgique / België / Belgium Sortiert nach Ort Sorted by city » For help, call me! DKV ASSIST - 24h International Free Call* 00800 365 24 365 In case of difficulties concerning the number 00800 please dial the relevant emergency number of the country: Bei unerwarteten Schwierigkeiten mit der Rufnummer 00800, wählen Sie bitte die Notrufnummer des Landes: Andorra / Andorra Latvia / Lettland » +34 934 6311 81 » +370 5249 1109 Austria / Österreich Liechtenstein / Liechtenstein » +43 362 2723 03 » +39 047 2275 160 Belarus / Weißrussland Lithuania / Litauen » 8 820 0071 0365 (national) » +370 5249 1109 » +7 495 1815 306 Luxembourg / Luxemburg Belgium / Belgien » +32 112 5221 1 » +32 112 5221 1 North Macedonia / Nordmazedonien Bosnia-Herzegovina / Bosnien-Herzegowina » +386 2616 5826 » +386 2616 5826 Moldova / Moldawien Bulgaria / Bulgarien » +386 2616 5826 » +359 2804 3805 Montenegro / Montenegro Croatia / Kroatien » +386 2616 5826 » +386 2616 5826 Netherlands / Niederlande Czech Republic / Tschechische Republik » +49 221 8277 9234 » +420 2215 8665 5 Norway / Norwegen Denmark / Dänemark » +47 221 0170 0 » +45 757 2774 0 Poland / Polen Estonia / Estland » +48 618 3198 82 » +370 5249 1109 Portugal / Portugal Finland / Finnland » +34 934 6311 81 » +358 9622 2631 Romania / Rumänien France / Frankreich » +40 264 2079 24 » +33 130 5256 91 Russia / Russland Germany / Deutschland » 8 800 7070 365 (national) » +49 221 8277 564 » +7 495 1815 306 Great Britain / Großbritannien Serbia / Serbien » 0 800 -

Pré-Inscriptions / Voor-Inschrijvingen LAERBEEK 2019

Pré-inscriptions / Voor-inschrijvingen LAERBEEK 2019 NOM Prénom S/G Cat. CP Commune Club Payé NAAM Voornaam PC Gemeente Club Betaald ADJOURI Amine M 1050 Ixelles perspective.brussels AKCAY Indiravus M 1083 Ganshoren Y AMRANI Jamal M 1000 Bruxelles BARIDEAU Thomas M 1190 Bruxelles Y BATTAILLE Marie-Laure F/V 1030 Schaerbeek Y BATTEUR Sébastien M 1030 Schaerbeek Y BEJAER Véronique F/V 1083 Ganshoren Y BIDAINE Luc M 1180 Uccle WPRC Y BILTRESSE Maxime M 7900 Leuze en hainaut Y BINDELS Gilles M 1780 Wemmel Y BOGHMANS Christine F/V 1780 Wemmel JCPMF Koekelberg Y BOUCLIER Maïté F/V 1780 Wemmel Y BOURDON Alain M 1083 Ganshoren Y BRECKPOT Benoit M 1070 Anderlecht Y BRUSSEEL Rony M 1080 Molenbeek Y BUONTIEMPO Olivier M 1082 Berchem-Sainte- Jcpm Y BURTON Richard M 1020 Laken Y CAMPOGRANDE Domenico M 1020 Laeken Y CAPIZZI Vincenza F/V 1731 Zellik Joggans Y CAVAS Fikret M 1020 Laeken Y CEUSTERS Morgane F/V 1060 Saint Gilles Y CHARLES Sophie F/V 1640 Rhode-Saint- WPRC Y COEURDEROI Quentin M 1090 Jette Joggans Y CONVENS Olivier M 1090 Jette Y COOLS Eva F/V 1840 Londerzeel Dé Loopclub Y CORNELIS Marie F/V 1700 Dilbeek Y CORNELIS Sophie F/V 1853 Strombeek-Bever Y CORREIA Fernando M 1040 Etterbeek Y CROISET Sophie F/V 1780 Wemmel Run In Brussels Y CUYVERS Dries M 1030 Schaerbeek perspective.brussels DE GRAVE Denis M 1000 Bruxelles Y DE GRAVE Julien M 1060 Saint Gilles Y 1 03-05-2019 Pré-inscriptions / Voor-inschrijvingen LAERBEEK 2019 NOM Prénom S/G Cat. -

Bernheim, Nele. "Fashion in Belgium During the First World War and the Case of Norine Couture." Fashion, Society, and the First World War: International Perspectives

Bernheim, Nele. "Fashion in Belgium during the First World War and the case of Norine Couture." Fashion, Society, and the First World War: International Perspectives. Ed. Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin and Sophie Kurkdjian. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021. 72–88. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350119895.ch-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 18:11 UTC. Copyright © Selection, editorial matter, Introduction Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards- Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian and Individual chapters their Authors 2021. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 5 Fashion in Belgium during the First World War and the case of Norine Couture N e l e B e r n h e i m What happens to civil life during wartime is a favorite subject of historians and commands major interest among the learned public. Our best source on the situation in Belgium during the First World War is Sophie De Schaepdrijver’s acclaimed book De Groote Oorlog: Het Koninkrijk Belgi ë tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (Th e Great War: Th e Kingdom of Belgium During the Great War). 1 However, to date, there has been no research on the Belgian wartime luxury trade, let alone fashion. For most Belgian historians, fashion during this time of hardship was the last of people’s preoccupations. Of course, fashion historians know better.2 Th e contrast between perception and reality rests on the clich é that survival and subsistence become the overriding concerns during war and that aesthetic life freezes—particularly the most “frivolous” of all aesthetic endeavors, fashion. -

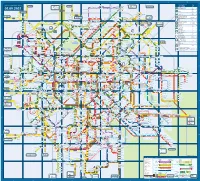

Vanaf À Partir Du From

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 BEZIENSWAARDIGHEDEN HALTE Jordaen POINTS D’INTÉRÊT ARRÊT VANAF À PARTIR DU FROM Puurs via Liezele Mechelen Drijpikkel Humbeek Kerk Malines Malderen Mechelen - Antwerpen POINTS OF INTEREST STOP Ennepetal Minnemolen Vilvoorde Heldenplein Vilvoorde Malines - Anvers Puurs via Willebroek Station Antwerpen 47 Anvers Koning Boudewijnstadion Heizel Boom via Londerzeel Vlierkens B2 Boom via Tisselt 47 58 Stade Roi Baudouin Hanssenspark Heysel 01.09.2021 Twee Leeuwenweg Vilvoorde 230 260 Blokken Heizel 250-251 460-461 Vier Fonteinen Atomium B3 Asse BRUPASS XL VTM Heysel Dendermonde Pellenberg A RING RING A 65 Heizel BRUPASS Station Kerk Machelen Brussels Expo Machelen B3 Windberg Heysel 231-232-820 Kerk Koningin Zellik Fabiola Keerbergen Luchthaven Brussel-Nationaal Dilbeek - Halle Kapelle-op-den-Bos Robbrechts Bicoque Kasteel Kampenhout Aéroport Bruxelles National Brussels Airport B8 Verbrande Brug Hoogveld Cortenbach Parkstraat Kaasmarkt Rijkendal Mercator De Béjar Buda Twyeninck Witloof Beaulieu Haacht Kortenbach Brussels National Airport 243-810 Luchthaven 56 Diegemstraat 56 65 Zaventem Kerk 57 Raedemaekers Bloemendal Buda Gare de Haren-Sud 80 VRT Dobbelenberg 470 Diamant D7 SAO DGHR Domaine Militaire Station Haren-Zuid 270-271 RTBF Hôpital Militaire DOO DGHR Militair Domein Haren Markt Bever De Villegas Mutsaard 47 Zandloper Magnolias Militair Hospitaal Biplan Basiliek van Koekelberg Tweedekker Specifieke prijs vanaf de luchthaven Bossaert-Basiliek 810 Magnolia Aérodrome 240 Expo Madelon Nieuwelaan 53 57 Antoon Van Oss -

MAANDBLAD VOOR DE BEWONERS VAN DE VLAAMSE RAND TAAL(ON)VRIENDELIJKHEID Geneeskunde Boet Daardoor Wel Aan Kwaliteit In

MAANDBLAD VOOR DE BEWONERS VAN DE VLAAMSE RAND TAAL(ON)VRIENDELIJKHEID geneeskunde boet daardoor wel aan kwaliteit in. Luc D'Hooghe: 'We vragen niet dat elke arts perfect meertalig IN BRUSSELSE ZIEKENHUIZEN is, maar een zekere gevoeligheid voor de taal en de cul tuur van de patiënt is we! belangrijk. Als je daar volledig buiten staat, kun je je ook niet inleven in zijn problemen. Geneeskunde Denken we bijvoorbeeld aan een zwaar hyperventilerende patiënt die op spoedgevallen wordt binnengebracht. Zo iemand is in paniek en communicatie is hier dan ook cru met de mond ciaal. Bij gebrek aan een degelijke kennis van het Neder lands gaat men dan maar meteen een cardiaal onderzoek doen. Ook in andere gevallen wordt maar al te vaak een vol tanden resem onderzoeken gedaan om pas daarna het probleem duidelijk te omschrijven. Anamnese, een goede ondervra In heel wat Brusselse ziekenhuizen weet ging, kan in dit kader kostenbesparend en efficiënt zijn. men nauwelijks dat in de hoofdstad ook Uiteraard speelt taal daarin een belangrijke rol: Nederlands wordt gesproken. Het is een oud zeer en de zaken verbeteren er niet op. Pipi in een potje 'Kijk', zegt dokter D'Hooghe, 'in 1993 maak In het Brusselse moeten de 100 ten we hierover een grondige studie en diensten in principe tweetalig wezen we op de lamentabele toestand. Anno zijn, maar in de realiteit is dat 1997 staan we nog niet veel verder.' dikwijls niet het geval. Veel hangt af van het ziekenhuis waaraan ze Luc D'Hooghe is huisarts in Vorst (zijn patiënten zijn voor verbonden zijn. -

Regenergy Factsheets.Pdf

RegEnergyRegEnergy „ An insight into strong urban - rural partnerships across North-West Europe „ RegEnergy IMPRINT Published February 2021 Climate Alliance European Secretariat | Headquarters Galvanistr. 28 60486 Frankfurt am Main Germany T. +49 69 717 139 -0 E. [email protected] Editing Svenja Enke, Climate Alliance Hélène Rizzotti , Climate Alliance Susanne Brandt, Climate Alliance Dr. Birgit Haupter, INFRASTRUKTUR & UMWELT Katrin Leuenberger, INFRASTRUKTUR & UMWELT Design Susanne Brandt, Climate Alliance Klima-Bündnis der europäischen Städte mit indigenen Völkern der Regenwälder | Alianza del Clima e. V. Amtsgericht Frankfurt am Main | VR10149 |Ust.IDNr. DE244331692 | Vorstandsvorsitzende: Andreas Wolter & Tine Heys FOREWORD RegEnergy RENEWABLE ENERGY REGIONS Maximise the share of renewable energies in the production and consumption mix in 9 regions of North-West Europe – that is our aim. We are 9 project partners from seven counties and seek to improve the region‘s carbon footprint. An important task considering that NWE is one of the EU’s highest energy consuming regions, currently still heavily dependent on non-renewable energy sources. As different as we are – from metropolitan regions, cities, rural communities, regional agencies, scientific institutions and renewable energy producers - we all adopt one common approach: building strong partnerships that connect the rural production with the urban demand of renewables. On the following pages, we present our projects and provide insights into the challenges. We invite you to get inspired by our experiences! Discover possibilities for turning waste into renewable energy, for the active support of municipalities for energy communities, or for smart solutions that can help dealing with limited grid capacity and an intermittent renewable energy supply. -

214 Bus Dienstrooster & Lijnroutekaart

214 bus dienstrooster & lijnkaart 214 Aalst Station Perron 5 Bekijken In Websitemodus De 214 buslijn (Aalst Station Perron 5) heeft 8 routes. Op werkdagen zijn de diensturen: (1) Aalst Station Perron 5: 04:25 - 23:20 (2) Aalst V.T.I.: 07:20 (3) Asse Station: 06:55 - 23:50 (4) Asse Station: 00:00 - 23:10 (5) Brussel Noord Afstaphalte: 04:40 - 22:40 (6) Koekelberg Simonis: 06:14 - 17:46 (7) Zellik Dorp: 15:22 - 16:12 (8) Zellik Drie Koningen: 12:05 - 12:18 Gebruik de Moovit-app om de dichtstbijzijnde 214 bushalte te vinden en na te gaan wanneer de volgende 214 bus aankomt. Richting: Aalst Station Perron 5 214 bus Dienstrooster 59 haltes Aalst Station Perron 5 Dienstrooster Route: BEKIJK LIJNDIENSTROOSTER maandag 04:25 - 23:20 dinsdag 04:25 - 23:20 Brussel Noord Opstaphalte woensdag 04:25 - 23:20 Brussel Rogier Place Charles Rogier - Karel Rogierplein, Brussel donderdag 04:25 - 23:20 Brussel Albert-Ii-Laan vrijdag 04:25 - 23:20 Boulevard Baudouin - Boudewijnlaan, Brussel zaterdag 04:25 - 23:20 Brussel Ijzer zondag 05:50 - 22:20 45 Boulevard d'Anvers, Brussel Sint-Jans-Molenbeek Sainctelette 17 Boulevard Léopold II - Leopold II-laan, Brussel 214 bus Info Ribaucourt Route: Aalst Station Perron 5 93-95 Boulevard Léopold II - Leopold II laan, Brussel Haltes: 59 Ritduur: 72 min Sint-Jans-Molenbeek Ourthe Samenvatting Lijn: Brussel Noord Opstaphalte, 179 Boulevard Léopold II - Leopold II laan, Brussel Brussel Rogier, Brussel Albert-Ii-Laan, Brussel Ijzer, Sint-Jans-Molenbeek Sainctelette, Ribaucourt, Sint- Koekelberg Simonis Jans-Molenbeek Ourthe, -

STI in Flanders DEPARTMENT of ECONOMY, SCIENCE & INNOVATION

STI in Flanders DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMY, SCIENCE & INNOVATION KONING ALBERT II-laan 35 bus 10 Science, Technology & Innovation 1030 Brussels www.ewi-vlaanderen.be Policy & Key Figures - 2016 STI in Flanders Science, Technology & Innovation Policy & Key Figures – 2016 2 Table of contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1 Science, Technology and Innovation system in Flanders .......................... 9 1 Competencies in the field of science, research and innovation .................................................. 10 1.1 Federalism in Belgium ............................................................................................................................. 10 1.2 Competencies in the field of science, research and innovation ...................................... 11 Direct support for R&D and innovation in the broad sense ....................................... 12 All research related to the community (= person-related) and the regional (= territorial related) competencies ................................................................................................................... 12 Access to finance ................................................................................................................................. 13 2 General orientations of Flemish STI policy ............................................................................................... 13 2.1 Instruments -

Ruimtelijke Herinrichting Van De Ring Rond Brussel (R0) - Deel Noord’

Gewestelijk ruimtelijk uitvoeringsplan ‘Ruimtelijke herinrichting van de Ring rond Brussel (R0) - deel Noord’ Scopingnota dd 28/06/2019 Scopingnota - p. 1 van 234 Gewestelijk ruimtelijk uitvoeringsplan ‘Ruimtelijke herinrichting van de Ring Het plan beoogt de ruimtelijke herinrichting van de R0 - deel Noord, zodat rond Brussel (R0) - deel Noord’ de infrastructuur verkeersveiliger wordt, de barrièrewerking van de Ring vermindert, de leefbaarheid in de omgeving verhoogt, en de multimodale bereikbaarheid van de regio verbetert. Meer weten? Zie hoofdstuk 3. Plandoelstelling en -voornemen De regio blijft groeien en nu al kampt de R0 met hoge intensiteiten en files, en kreunt de omgeving onder het sluipverkeer. De weginfrastructuur is verouderd, complex en onveilig, en werkt als een barrière voor zachte weggebruikers en openbaar vervoer; er is ook een gebrek aan alternatieven voor de auto. De R0 is eveneens een barrière voor fauna en flora. Meer weten? zie hoofdstuk 2. Historiek, context en analyse Het (mogelijk) plangebied is het projectgebied rond de Ring rond Brussel, tussen en met inbegrip van de verkeerswisselaars R0/E40 Groot- Bijgaarden en R0/E40 Sint-Stevens- Woluwe. Meer weten? zie hoofdstuk 4. het Plangebied Enerzijds betreft het plan de (her)aanleg van weginfrastructuur en anderzijds ingrepen om deze weginfrastructuur ruimtelijk in te passen, dwarsverbindingen voor zacht verkeer en groenblauwe verbindingen te realiseren, enz. Alle MER disciplines worden relevant geacht te onderzoeken. Meer weten? zie hoofdstuk 5. Scoping De Ring rond Brussel (R0) is oude en verouderde infrastructuur. De eerste delen dateren van ruim 60 jaar geleden en de infrastructuur is als een harde barrière voor mens en dier in de omgeving ingeplant. -

STI in Flanders

STI in Flanders DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMY, SCIENCE & INNOVATION KONING ALBERT II-laan 35 bus 10 Science, Technology & Innovation 1030 Brussels www.ewi-vlaanderen.be Policy & Key Figures - 2017 STI in Flanders Science, Technology & Innovation Flanders Policy & Key Figures 2017 Colophon STI in Flanders is a publication of The Flemish Government, Department Economy, Science and Innovation Flemish Government Departement EWI Koning Albert II-laan 35, bus 10 1030 Brussel Tel.: 02 553 59 80 [email protected] www.ewi-vlaanderen.be Publisher: Johan Hanssens, Secretaris-generaal Authors: Niko Geerts, Monica Van Langenhove, Peter Viaene, Pierre Verdoodt Date of publication: December 2017 Content revised and enlarged version finalised on 1st of September 2017 The reproduction of content of the “STI in Flanders” publication is only allowed with a reference to the source. The Department Economy, Science and Innovation is not liable for any use of information in this edition. Coverfoto © www.shutterstock.com D/2017/3241/344 Foreword The Department of Economy, Science and Innovation of the Flemish Government is pleased to present its fifth edition of the “STI in Flanders”. The aim is to present in-depth information about Science, Technology and Innovation policy in Flanders, highlight important figures or indicators, describe the broad context and the performance of the research and innovation landscape, and list both the main actors and the public entities engaged in the field of R&D and innovation. The publication is updated on a regular basis. The Government of Flanders is aware of the importance of research and innovation as a necessary condition for maintaining wealth and well-being in Flanders. -

WDP Realises Acquisition of Additional Site in Asse Via Capital Increase of 12 Million Euros

PRESS RELEASE Wednesday, 17 October 2018, 8.00 am Regulated information 1 Press release – 17 October 2018 WDP realises acquisition of additional site in Asse via capital increase of 12 million euros Issue of 119,226 new WDP shares of (rounded) 104.36 euros per share - Consequences under transparency law WDP Asse-Zellik: 180,000 m² for logistics properties WDP has acquired an additional site in Asse, measuring some 52,000 m², consisting of both vacant lots and developed area. Over time, WDP wants to partially redevelop this site – in combination with the previously acquired properties, including the recently announced 2 neighbouring site – to further expand its logistics park in Asse-Zellik. This acquisition, for an overall investment value of 12.4 million euros, was realised today by means of a contribution in kind of the site in WDP, in exchange for 119,226 new WDP shares. Today, 17 October 2018, the Board of Directors of the manager, De Pauw NV, using the authorised capital, approved this transaction, resulting in a capital increase of (around) 12 million euros and the issue of 119,226 new WDP shares. These shares are expected to be listed on Euronext Brussels and Amsterdam starting on 18 October 2018. This issue price amounts to (rounded) 104.36 euros per share. Press release – 17 October 2018 WDP REALISES ACQUISITION OF ADDITIONAL SITE IN ASSE WITH A CAPITAL INCREASE OF 12.4 MILLION EUROS The acquisition of this site was completed today, 17 October 2018, by a contribution in kind of the site in WDP in exchange for 119,226 new WDP shares.