HALF-VIRGIN by ALEXANDER GREGORY POLLACK B.A. Emory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birdlife International for the Input of Analyses, Technical Information, Advice, Ideas, Research Papers, Peer Review and Comment

UNEP/CMS/ScC16/Doc.10 Annex 2b CMS Scientific Council: Flyway Working Group Reviews Review 2: Review of Current Knowledge of Bird Flyways, Principal Knowledge Gaps and Conservation Priorities Compiled by: JEFF KIRBY Just Ecology Brookend House, Old Brookend, Berkeley, Gloucestershire, GL13 9SQ, U.K. June 2010 Acknowledgements I am grateful to colleagues at BirdLife International for the input of analyses, technical information, advice, ideas, research papers, peer review and comment. Thus, I extend my gratitude to my lead contact at the BirdLife Secretariat, Ali Stattersfield, and to Tris Allinson, Jonathan Barnard, Stuart Butchart, John Croxall, Mike Evans, Lincoln Fishpool, Richard Grimmett, Vicky Jones and Ian May. In addition, John Sherwell worked enthusiastically and efficiently to provide many key publications, at short notice, and I’m grateful to him for that. I also thank the authors of, and contributors to, Kirby et al. (2008) which was a major review of the status of migratory bird species and which laid the foundations for this work. Borja Heredia, from CMS, and Taej Mundkur, from Wetlands International, also provided much helpful advice and assistance, and were instrumental in steering the work. I wish to thank Tim Jones as well (the compiler of a parallel review of CMS instruments) for his advice, comment and technical inputs; and also Simon Delany of Wetlands International. Various members of the CMS Flyway Working Group, and other representatives from CMS, BirdLife and Wetlands International networks, responded to requests for advice and comment and for this I wish to thank: Olivier Biber, Joost Brouwer, Nicola Crockford, Carlo C. Custodio, Tim Dodman, Roger Jaensch, Jelena Kralj, Angus Middleton, Narelle Montgomery, Cristina Morales, Paul Kariuki Ndang'ang'a, Paul O’Neill, Herb Raffaele and David Stroud. -

Do Racing Pigeons (Columba Livia Domestica); Have a Colour Or Calorific Preference?

University of Chester Do racing pigeons (Columba livia domestica); have a colour or calorific preference? A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF CHESTER FOR THE DEGREE OF: ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR AND WELFARE BI6110 – 2012/2013 Department of Biological Sciences Student: Yasmin Bailey Supervisor: John Cartwright Word Count Abstract 327 Main Body 8346 DECLARATION I certify that this work is original in its entirety and has never before been submitted for any form of assessment. The practical work, data analysis and presentation and written work presented are all my own work unless otherwise stated. Signed ……………………………………………………………. Yasmin Bailey Page 1 of 44 Abstract Pigeon racing was immensely popular amongst male industrial workers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Johnes, 2007). This study offers an overview of pigeon racing in this period, before moving on to discover if racing pigeons (Columba livia domestica), have a preference to their food; and if so, could this help the pigeon racers of today? The subjects used in this study consisted of eight racing pigeons (Columba livia domestica) , four cocks and four hens all around the same age of 28 days. The experiments carried out were split into three parts. Experiment one involved colour preference, where the pigeons were given a different colour feed each day, for ten days. The second experiment involved colour preference again, however the pigeons were given a mixture of all five colours of feed, blue, red, green, yellow and natural, for another ten days. Experiment three then moved onto see whether pigeons have a calorie preference, so they were given a high calorie diet one day, a low calorie diet the next and then a mixture of both high and low calories the following day, causing a sequence that continued for twelve days. -

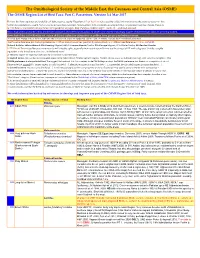

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

CELSYS Holds Third Annual International Comic and Illustration Contest for Art Students

November, 12, 2019 CELSYS,Inc CELSYS Holds Third Annual International Comic and Illustration Contest for Art Students November 12, 2019 - CELSYS, creators of the acclaimed Clip Studio Paint creative software, will host their third annual international comic and illustration contest for art students, the “International Comic/Manga School Contest,” with submissions accepted beginning Thursday, January 9, 2020. Through this contest, students of all ages receive the opportunity to have their works critiqued by a panel of professional artists and even have their art published for viewers across the globe to see. Contest winners are additionally eligible for cash prizes and digital art goods. This year, the theme of the International Comic/Manga School Contest is “Promise.” The contest is made possible in part through the generous sponsorship and support of a number of entities well -known in the worlds of comics, manga, pop culture and digital art. This year, three entities have pledged special sponsorship. These entities are digital art tablet and pen manufacturer Wacom and Japanese comics and manga publishing giants Shueisha and KADOKAWA. 2019’s contest saw participation from 639 schools in 67 countries with over 1,400 individual pieces submitted for consideration across multiple categories. The 2020 contest is expected to further grow the number of participating schools and submitted works. See below for a list of categories, sponsors and an introduction to 2020’s special guest judges. Contest official website: https://www.clipstudio.net/promotion/comiccontest/en/ -

Proposals Inspired by Nature

PROPOSALS INSPIRED BY NATURE London College of Communication. Ideas to complement and nurture the Copyright © 2015. Greater London National Park (GLNP) 1. ALGAE ROUNDABOUTS 2. GREEN BUS ROUTES / SAFARI 3. WALK ON THE WILD SIDE 4. LAMP POST BIRD NESTING 5. SKYLARK ROOF GARDENS 6. SEED BOMBING INITIATIVE 7. RECLAIMING PUBLIC SPACE 8. FARMERS’ MARKET PRESS 9. WILD SWIMMING / AQUA THERAPY 10. HIVE WALKING NETWORK ALGAE ROUNDABOUTS Credits WHAT London College of Communication: A creative proposal for algae installations integrated into roundabouts. Design by Reuel Cuffie, Vanessa Diep This is an innovative and transformative idea which could bring huge and William Jackson Mitchell. positive health impacts, employability benefits and decarbonisation Copyright © 2015. initiatives to the city – helping cut air pollution and public exposure to it, while creating beautiful hydrobiology installations which not only consume carbon dioxide but also produce energy to run night-time street lighting. Dimensions of prosperity WHY • Health Air pollution harms health and causes thousands of premature • Environmental sustainability deaths every year. Children, older citizens and people with asthma are • Infrastructural security particularly vulnerable, and low-income and ethnic minority groups are also disproportionately affected. Some areas of congested London exceed legal limits making air pollution an invisible public health crisis. Roundabouts are ideally situated dead-spaces which can provide locations to house a solution. Actors HOW • Greater London Authority Councils could work alongside organisations (such as GLNP and and Councils The Healthy Air Campaign) to develop roadside algae installations which • Transport for London not only respond to areas with the most serious pollution levels, but also • Algal technology companies create new spaces of environmental sustainability and community pride, • Local businesses providing jobs and training in dynamic new city ecosystems. -

A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi

A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi by Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire 2006 Tauraco Research Report No. 8 Tauraco Press, Liège, Belgium A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi by Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire 2006 Tauraco Research Report No. 8 Tauraco Press, Liège, Belgium Tauraco Research Report No. 8 (2006) A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi ISBN 2-87225-003-4 Dépôt légal: D/2006/6838/06 Published April 2006 © F. Dowsett-Lemaire All rights reserved. Published by R.J. Dowsett & F. Lemaire, 12 rue Louis Pasteur, Grivegnée, Liège B-4030, Belgium. Other Tauraco Press publications include: The Birds of Malawi 556 pages, 16 colour plates, 625 species distribution maps, Tauraco Press & Aves (Liège, Belgium) Pbk, April 2006, ISBN 2-87225-004-2, £25 A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi by Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire CONTENTS An annotated list and life history of the birds of Nyika National Park, Malawi-Zambia ...........................1-64 Notes supplementary to The Birds of Malawi (2006) ..............65-121 Birds of Nyika National Park 1 Tauraco Research Report 8 (2006) An annotated list and life history of the birds of Nyika National Park, Malawi-Zambia by Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire INTRODUCTION The Nyika Plateau is the largest montane complex in south-central Africa, with an area of some 1800 km² above the 1800 m contour – above which montane conditions prevail. The scenery is spectacular, with the upper plateau covered by c. 1000 km² of gently rolling Loudetia-Andropogon grassland, dotted about with small patches of low-canopy forest in hollows. Numerous impeded drainage channels support dambos. These high-altitude Myrica-Hagenia forest patches (at 2250-2450 m) are often no more than 1-2 ha in size, and cover about 2-3% of the central plateau. -

Birds from Gabon and Moyen Congo

-"L I E) RAR.Y OF THE UN IVLR5ITY or ILLINOIS 590.5 FI V.41 cop. 3 NAiUhAL HISiuiSY SURVEY ,3 birds from Gabon and Moyen Congo AUSTIN L. RAND HERBERT FRIEDMANN MELVIN A. TRAYLOR, JR. fjMnoisiniiiiuHfiis FIELDIANA: ZOOLOGY VOLUME 41, NUMBER 2 Published by CHICAGO NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM NOVEMBER 25, 1959 HIST-: birds from Gabon and Moyen Congo AUSTIN L. RAND Chief Curator, Department of Zoology Chicago Natural History Museum HERBERT FRIEDMANN Curator of Birds, United States National Museum MELVIN A. TRAYLOR, JR. Associate Curator, Division of Birds Chicago Natural History Museum FIELDIANA: ZOOLOGY VOLUME 41, NUMBER 2 Published by CHICAGO NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM NOVEMBER 25, 1959 This paper is dedicated to PROFESSOR ERWIN STRESEMANN on the occasion of his seventieth birthday. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 59-15918 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY CHICAGO NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM PRESS V.HI Ot? I/O , o Contents PAGE Introduction 223 Aschemeier's Itinerary 228 Beatty's Itinerary 231 Faunal Relationships 233 Acknowledgments 238 List of Birds 239 References 405 List of Families 411 221 Introduction In introducing a new study of the birds of Gabon we are mindful of the fact that the beginnings of our knowledge of the bird life of that portion of western Africa were connected with an American museum, the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. However, there cannot be said to be any connection between that historical fact and the present study, as the intervening century has seen little active interest in Gabon on the part of American ornithologists. Even the early interest in Gabon at the Philadelphia institution was not due to any advance planning on the part of the Academy. -

S Angola on Their Way South

Important Bird Areas in Africa and associated islands – Angola ■ ANGOLA W. R. J. DEAN Dickinson’s Kestrel Falco dickinsoni. (ILLUSTRATION: PETE LEONARD) GENERAL INTRODUCTION December to March. A short dry period during the rains, in January or February, occurs in the north-west. The People’s Republic of Angola has a land-surface area of The cold, upwelling Benguela current system influences the 1,246,700 km², and is bounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, climate along the south-western coast, and this region is arid in the Republic of Congo to the north-west, the Democratic Republic of south to semi-arid in the north (at about Benguela). Mean annual Congo (the former Zaïre) to the north, north-east, and east, Zambia temperatures in the region, and on the plateau above 1,600 m, are to the south-east, and Namibia to the south. It is divided into 18 below 19°C. Areas with mean annual temperatures exceeding 25°C (formerly 16) administrative provinces, including the Cabinda occur on the inner margin of the Coast Belt north of the Queve enclave (formerly known as Portuguese Congo) that is separated river and in the Congo Basin (Huntley 1974a). The hottest months from the remainder of the country by a narrow strip of the on the coast are March and April, during the period of heaviest Democratic Republic of Congo and the Congo river. rains, but the hottest months in the interior, September and October, The population density is low, c.8.5 people/km², with a total precede the heaviest rains (Huntley 1974a). -

Mangroves As Habitat

MANGROVES AS HABITAT MANGROVES AS HABITAT 2 - 1 CONTENTS SECTION 2 WHAT LIVES IN MANGROVES? ......................................................................................... 2 How Are Mangroves and Other Plants Adapted to Live in Wetland Conditions? 2 How Are Animals Adapted to Live in Mangroves? .............................................. 3 Roots and Root Dwellers ..................................................................................... 4 How intertidal animals meet their needs through adaptation............................ 5 What Eats What ……………………………………………………………………………………………... 6 Food Chains and Food Webs ............................................................................... 7 Mangrove Habitat Study …………………………………………………………………………………. 9 Activity 2-A: Spot the Difference: Mangroves.................................................................10 Activity 2-B: Mangrove Food Web.................................................................................. 12 Activity 2-C: Mangrove Story Board................................................................................ 17 STORY BOARD CUT OUTS ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 21 Activity 2-D: Touchy-Feely Bag....................................................................................... 40 Activity 2-E: Living Web ................................................................................................. 42 Activity 2-F: Mr. Frog's Dream ....................................................................................... 44 Activity -

Simple Nature Activities for Kids

SIMPLE NATURE ACTIVITIES FOR KIDS 1. ANIMAL CHARADES 4. FEEL A ROCK (20 MIN) (15 MIN) AIM: To think about how living things move and sound AIM: To observe with the senses other than sight AGES: Grades 1-7, max. 30 participants AGES: All ages SPACE: Anywhere dry SPACE: Anywhere dry MATERIALS: Charade cards (30) MATERIALS: Rocks of different shapes and sizes, enough for each Activity: Get the kids to silently act out charades that include the participant (or cones or leaves or any objects from nature) name of the animal, which environment it’s in, and what it’s doing. ACTIVITY: Sit/stand everyone in a circle with their eyes closed. (i.e. a snake slithering through grass). Hand a rock to each person, hands behind their backs. Allow them a couple minutes to get to know their rock by feeling. Then collect the rocks. The players pass the rock around the circle 2. NOAH’S ARK behind their backs. When they find their rock they keep it, but (10 MIN) continue to pass the other rocks around the circle until everyone AIM: To practice animal movements/sounds and recognize them; thinks they have found their rock. OR when they find their rock, a fun way to split into groups they step back out of the circle. Can everyone find the correct AGES: All ages rock? (Variation: use a cone or any other object such as a shell MATERIALS: Pairs of matching animal cards from nature). SPACE: Anywhere dry ACTIVITY: Give each kid the name of an animal that has a distinct movement or shape and have them find their partner. -

Jafer Birds of Lonar Crater Lake 1125

NOTE ZOOS' PRINT JOURNAL 22(1): 2547-2550 parts. The vegetation appears to be of a stunted form and completely deciduous in nature, dominated with Butea A PRELIMINARY OBSERVATION ON THE monosperma, Aegle marmelos, Zizyphus oenoplia, Lantana camara, Cassia auriculata, Capparis sp. etc. BIRDS OF LONAR CRATER LAKE, (iii) The rim and outside crater: The Lonar crater has a BULDHANA DISTRICT, MAHARASHTRA 30m high rim with a diameter averaging 1830m at the rim crest; the northeastern side is much open. The outside of the Muhamed Jafer Palot crater has very gentle slopes, which eventually merges with the surrounding countryside interspersed with agricultural Western Ghats Field Research Station, Zoological Survey of India, lands. Kozhikode, Kerala 673002, India Even though the Lonar crater has a very small area, the Email: [email protected] diversity of different micro-ecosystems and the micro-climatic conditions accommodates a total of 110 species of birds Lonar lake (19059'N-74034'E) is situated in Mehkar taluka belonging to 41 families (Table 1). Of these, 22 are migratory, of Buldhana district of Maharashtra. This is the only crater 80 are residents and eight are considered to be local migrants in basaltic rock formed by the meteoritic impact in India, (Abdulali, 1981). The number of species recorded was high ranking third largest in the world. The Lonar crater has a on the rim and outside the crater (91), followed by slopes of circular outline with a diameter of 1830m and a depth of the crater (89) and 35 species from the lake and its basin. Birds 150m with steep vertical slopes. -

Guide to the National Museum of Ireland Natural History

Guide to the National Museum of Ireland Natural History Natural History Guide to the National Museum of Ireland Natural History 1 Contents Introduction 5 The Collections 10 Irish Fauna: Ground Floor 15 Mammals of the World: First Floor 21 Steps in Evolution: Second Floor (Lower Balcony, South Side) 26 Birds of a Feather: Second Floor (Lower Balcony, North Side) 31 Mating Game: Second Floor (Lower Balcony, East End) 36 Crystal Jellies: Third Floor (Upper Balcony) 39 Taxonomy Trail: Third Floor (Upper Balcony, North Side) 41 Underwater Worlds: Third Floor (Upper Balcony, South Side) 44 Guide to the National Museum of Ireland - Natural History © National Museum of Ireland, Dublin, 2005 ISBN 0-901777-43-9 Text: Nigel T. Monaghan Photography: Valerie Dowling and Noreen O'Callaghan All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, broadcast or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission in writing from the publishers. A floor plan is included in the back of this guide book. Introduction The Natural History Museum was built in 1856 to house the Royal Dublin Society’s growing collections, which had expanded continually since the late eighteenth century. The building is a ‘cabinet-style’ museum designed to showcase a wide-ranging and comprehensive zoological collection and has changed little in over a century. Often described as a ‘museum of a museum’, with its ten thousand exhibits it provides a glimpse of the natural world that has delighted many generations of visitors since the doors opened in 1857.