Case 1996.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birdlife International for the Input of Analyses, Technical Information, Advice, Ideas, Research Papers, Peer Review and Comment

UNEP/CMS/ScC16/Doc.10 Annex 2b CMS Scientific Council: Flyway Working Group Reviews Review 2: Review of Current Knowledge of Bird Flyways, Principal Knowledge Gaps and Conservation Priorities Compiled by: JEFF KIRBY Just Ecology Brookend House, Old Brookend, Berkeley, Gloucestershire, GL13 9SQ, U.K. June 2010 Acknowledgements I am grateful to colleagues at BirdLife International for the input of analyses, technical information, advice, ideas, research papers, peer review and comment. Thus, I extend my gratitude to my lead contact at the BirdLife Secretariat, Ali Stattersfield, and to Tris Allinson, Jonathan Barnard, Stuart Butchart, John Croxall, Mike Evans, Lincoln Fishpool, Richard Grimmett, Vicky Jones and Ian May. In addition, John Sherwell worked enthusiastically and efficiently to provide many key publications, at short notice, and I’m grateful to him for that. I also thank the authors of, and contributors to, Kirby et al. (2008) which was a major review of the status of migratory bird species and which laid the foundations for this work. Borja Heredia, from CMS, and Taej Mundkur, from Wetlands International, also provided much helpful advice and assistance, and were instrumental in steering the work. I wish to thank Tim Jones as well (the compiler of a parallel review of CMS instruments) for his advice, comment and technical inputs; and also Simon Delany of Wetlands International. Various members of the CMS Flyway Working Group, and other representatives from CMS, BirdLife and Wetlands International networks, responded to requests for advice and comment and for this I wish to thank: Olivier Biber, Joost Brouwer, Nicola Crockford, Carlo C. Custodio, Tim Dodman, Roger Jaensch, Jelena Kralj, Angus Middleton, Narelle Montgomery, Cristina Morales, Paul Kariuki Ndang'ang'a, Paul O’Neill, Herb Raffaele and David Stroud. -

Do Racing Pigeons (Columba Livia Domestica); Have a Colour Or Calorific Preference?

University of Chester Do racing pigeons (Columba livia domestica); have a colour or calorific preference? A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF CHESTER FOR THE DEGREE OF: ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR AND WELFARE BI6110 – 2012/2013 Department of Biological Sciences Student: Yasmin Bailey Supervisor: John Cartwright Word Count Abstract 327 Main Body 8346 DECLARATION I certify that this work is original in its entirety and has never before been submitted for any form of assessment. The practical work, data analysis and presentation and written work presented are all my own work unless otherwise stated. Signed ……………………………………………………………. Yasmin Bailey Page 1 of 44 Abstract Pigeon racing was immensely popular amongst male industrial workers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Johnes, 2007). This study offers an overview of pigeon racing in this period, before moving on to discover if racing pigeons (Columba livia domestica), have a preference to their food; and if so, could this help the pigeon racers of today? The subjects used in this study consisted of eight racing pigeons (Columba livia domestica) , four cocks and four hens all around the same age of 28 days. The experiments carried out were split into three parts. Experiment one involved colour preference, where the pigeons were given a different colour feed each day, for ten days. The second experiment involved colour preference again, however the pigeons were given a mixture of all five colours of feed, blue, red, green, yellow and natural, for another ten days. Experiment three then moved onto see whether pigeons have a calorie preference, so they were given a high calorie diet one day, a low calorie diet the next and then a mixture of both high and low calories the following day, causing a sequence that continued for twelve days. -

1 Restoring Scientific Integrity in Policy Making February 18, 2004

Restoring Scientific Integrity in Policy Making February 18, 2004 Science, like any field of endeavor, relies on freedom of inquiry; and one of the hallmarks of that freedom is objectivity. Now, more than ever, on issues ranging from climate change to AIDS research to genetic engineering to food additives, government relies on the impartial perspective of science for guidance. President George H.W. Bush, April 23, 1990 Successful application of science has played a large part in the policies that have made the United States of America the world’s most powerful nation and its citizens increasingly prosperous and healthy. Although scientific input to the government is rarely the only factor in public policy decisions, this input should always be weighed from an objective and impartial perspective to avoid perilous consequences. Indeed, this principle has long been adhered to by presidents and administrations of both parties in forming and implementing policies. The administration of George W. Bush has, however, disregarded this principle. When scientific knowledge has been found to be in conflict with its political goals, the administration has often manipulated the process through which science enters into its decisions. This has been done by placing people who are professionally unqualified or who have clear conflicts of interest in official posts and on scientific advisory committees; by disbanding existing advisory committees; by censoring and suppressing reports by the government’s own scientists; and by simply not seeking independent scientific advice. Other administrations have, on occasion, engaged in such practices, but not so systematically nor on so wide a front. Furthermore, in advocating policies that are not scientifically sound, the administration has sometimes misrepresented scientific knowledge and misled the public about the implications of its policies. -

Binbin Li Assistant Professor in Environmental Sciences, Duke Kunshan University

Binbin Li Assistant Professor in Environmental Sciences, Duke Kunshan University Phone: +8613810251904, Email: [email protected] EDUCATION Duke University, Nicholas School of the Environment (Durham, NC, USA) • Ph.D, Environment, Aug 2012 – May 2017. • Major Advisor: Stuart Pimm • Committee members: Jeff Vincent, Alex Pfaff, Jennifer Swenson University of Michigan, School of Natural Resources and Environment (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) • Master of Science, Natural Resources and Environment: Conservation biology and Environmental Informatics, Aug 2010 - April 2012 • Thesis: Effects of feral cats on the evolution of antipredator behaviors in the Aegean island lizard Podarcis erhardii. Peking University (Beijing, China) • Bachelor of Arts, Life Sciences with dual degree in Economics, Sep 2006 - Jul 2010 • Peking University Student Government, President of Dept. of International Communication Student Government of School of Environmental Sciences, President of Dept. of Activity, planning student orientation and social events • Thesis: Influence of Monoculture on Fauna diversity - Comparison of biodiversity in Japanese Larch (Larix kaempferi) monoculture and native secondary forest. WORK EXPERIENCE Duke Kunshan University, Environmental Research Center (Kunshan, Jiangsu, China) Assistant Professor of Environmental Sciences, Jul 2017-now • Responsible for teaching in Environmental Policy Master Program at Duke Kunshan University • Research on conservation biology AWARDS AND FUNDING • Young Conservation Leader, Birdlife International (2018) • Candidate -

Laudatio Stuart Pimm

The Dr A.H. Heineken Prize for Environmental Sciences 2006 The work of Professor Stuart L. Pimm presented by Professor Gert Jan F. van Heijst, Chairperson of the Jury of the Dr A.H. Heineken Prize for Environmental Sciences Prize citation: for 'his research on species extinction and conservation' Professor Pimm, The jury of the Dr A.H. Heineken Prize for Environmental Sciences has unanimously decided to award you the prize for 2006 for your research on species extinction and conservation. You are one of the leading and most influential biologists working in the field of biodiversity and its preservation, which is evident from the enviable number of times your name is quoted in publications of interest to us scientists, such as New Scientist, Nature and Science. Even at an early stage in your career, you aroused controversy in your publication Food Webs, in which you explained that the extinction of species within an ecological system has repercussions for the preservation of other species in that system. Biodiversity consists overwhelmingly of organisms at the higher trophic levels. In the abundant group of insects, for example, over 95% have been found to be at the higher trophic levels, so that any loss at the lower trophic levels has very serious consequences for the higher, more specialised levels. In other words, if a species at the bottom of the food chain extincts, the repercussions are felt throughout the food web. It was you who coined the term 'food chain' and used it in scientific models that have gone on to inspire many scientists. -

The Biodiversity–Ecosystem Function Debate in Ecology

Provided for non-commercial research and educational use only. Not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use. This chapter was originally published in the book Handbook of The Philosophy of Science: Philosophy of Ecology. The copy attached is provided by Elsevier for the author’s benefit and for the benefit of the author’s institution, for non-commercial research, and educational use. This includes without limitation use in instruction at your institution, distribution to specific colleagues, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including without limitation commercial reprints, selling or licensing copies or access, or posting on open internet sites, your personal or institution’s website or repository, are prohibited. For exceptions, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier's permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial From deLaplante Kevin, and Picasso Valentin, The Biodiversity-Ecosystem Function Debate in Ecology. In: Dov M. Gabbay, Paul Thagard and John Woods, editors, Handbook of The Philosophy of Science: Philosophy of Ecology. San Diego: North Holland, 2011, pp. 169-200. ISBN: 978-0-444-51673-2 © Copyright 2011 Elsevier B. V. North Holland. Author's personal copy THE BIODIVERSITY–ECOSYSTEM FUNCTION DEBATE IN ECOLOGY Kevin deLaplante and Valentin Picasso 1 INTRODUCTION Population/community ecology and ecosystem ecology present very different per- spectives on ecological phenomena. Over the course of the history of ecology there has been relatively little interaction between the two fields at a theoretical level, despite general acknowledgment that many ecosystem processes are both influ- enced by and constrain population- and community-level phenomena. -

Human Impacts on the Rates of Recent, Present, and Future Bird Extinctions

Human impacts on the rates of recent, present, and future bird extinctions Stuart Pimm*†, Peter Raven†‡, Alan Peterson§, Çag˘anH.S¸ ekerciog˘lu¶, and Paul R. Ehrlich¶ *Nicholas School of the Environment and Earth Sciences, Duke University, Box 90328, Durham, NC 27708; ‡Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box 299, St. Louis, MO 63166; §P.O. Box 1999, Walla Walla, WA 99362; and ¶Center for Conservation Biology, Department of Biological Sciences, Stanford University, 371 Serra Mall, Stanford, CA 94305-5020 Contributed by Peter Raven, June 4, 2006 Unqualified, the statement that Ϸ1.3% of the Ϸ10,000 presently ‘‘missing in action,’’ not recently recorded in its native habitat known bird species have become extinct since A.D. 1500 yields an that human actions have largely destroyed. This assumption estimate of Ϸ26 extinctions per million species per year (or 26 prevents terminating conservation efforts prematurely, even as E͞MSY). This is higher than the benchmark rate of Ϸ1E͞MSY it again underestimates the total number of extinctions. Finally, before human impacts, but is a serious underestimate. First, rapidly declining species will lose most of their populations and Polynesian expansion across the Pacific also exterminated many thus their functional roles within ecosystems long before their species well before European explorations. Second, three factors actual demise (3, 4). increase the rate: (i) The number of known extinctions before 1800 We explore the often-unstated assumptions about extinction is increasing as taxonomists describe new species from skeletal numbers to understand the various estimates. Starting before remains. (ii) One should calculate extinction rates over the years 1500 and the period of first human contact with bird species, we since taxonomists described the species. -

Planetary Boundaries for Biodiversity José Montoya, Ian Donohue, Stuart Pimm

Planetary Boundaries for Biodiversity José Montoya, Ian Donohue, Stuart Pimm To cite this version: José Montoya, Ian Donohue, Stuart Pimm. Planetary Boundaries for Biodiversity: Implau- sible Science, Pernicious Policies. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2018, 33 (2), pp.71-73. 10.1016/j.tree.2017.10.004. hal-02404725v2 HAL Id: hal-02404725 https://hal-univ-tlse3.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02404725v2 Submitted on 26 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Forum 10-fold background. Despite widespread To address concerns that extinction rates Planetary Boundaries criticisms, the tipping-point claim per- are an inappropriate metric, the biodiver- for Biodiversity: sists, with recent reproduction of the orig- sity boundary is renamed as ‘biosphere ii inal claim [1] and statements that the integrity’ [3]. Two static measures of bio- Implausible Science, threshold is ‘not arbitrary’, emerges from diversity replace rates: phylogenetic vari- Pernicious Policies ‘massive amounts of data’ from many ability and functional diversity. Problems 1, fields, and that ‘no one is saying that of definition apart, reliable estimates for José M. Montoya, * ’ ‘ 2 the idea is wrong , despite massive anything resembling these are impossible Ian Donohue, and ’ 3 breakthroughs in counting extinctions . -

The Sixth Great Extinction Donations Events "Soon a Millennium Will End

The Rewilding Institute, Dave Foreman, continental conservation Home | Contact | The EcoWild Program | Around the Campfire About Us Fellows The Pleistocene-Holocene Event: Mission Vision The Sixth Great Extinction Donations Events "Soon a millennium will end. With it will pass four billion years of News evolutionary exuberance. Yes, some species will survive, particularly the smaller, tenacious ones living in places far too dry and cold for us to farm or graze. Yet we Resources must face the fact that the Cenozoic, the Age of Mammals which has been in retreat since the catastrophic extinctions of the late Pleistocene is over, and that the Anthropozoic or Catastrophozoic has begun." --Michael Soulè (1996) [Extinction is the gravest conservation problem of our era. Indeed, it is the gravest problem humans face. The following discussion is adapted from Chapters 1, 2, and 4 of Dave Foreman’s Rewilding North America.] Click Here For Full PDF Report... or read report below... Many of our reports are in Adobe Acrobat PDF Format. If you don't already have one, the free Acrobat Reader can be downloaded by clicking this link. The Crisis The most important—and gloomy—scientific discovery of the twentieth century was the extinction crisis. During the 1970s, field biologists grew more and more worried by population drops in thousands of species and by the loss of ecosystems of all kinds around the world. Tropical rainforests were falling to saw and torch. Wetlands were being drained for agriculture. Coral reefs were dying from god knows what. Ocean fish stocks were crashing. Elephants, rhinos, gorillas, tigers, polar bears, and other “charismatic megafauna” were being slaughtered. -

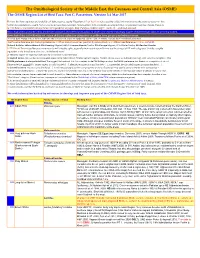

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

Proposals Inspired by Nature

PROPOSALS INSPIRED BY NATURE London College of Communication. Ideas to complement and nurture the Copyright © 2015. Greater London National Park (GLNP) 1. ALGAE ROUNDABOUTS 2. GREEN BUS ROUTES / SAFARI 3. WALK ON THE WILD SIDE 4. LAMP POST BIRD NESTING 5. SKYLARK ROOF GARDENS 6. SEED BOMBING INITIATIVE 7. RECLAIMING PUBLIC SPACE 8. FARMERS’ MARKET PRESS 9. WILD SWIMMING / AQUA THERAPY 10. HIVE WALKING NETWORK ALGAE ROUNDABOUTS Credits WHAT London College of Communication: A creative proposal for algae installations integrated into roundabouts. Design by Reuel Cuffie, Vanessa Diep This is an innovative and transformative idea which could bring huge and William Jackson Mitchell. positive health impacts, employability benefits and decarbonisation Copyright © 2015. initiatives to the city – helping cut air pollution and public exposure to it, while creating beautiful hydrobiology installations which not only consume carbon dioxide but also produce energy to run night-time street lighting. Dimensions of prosperity WHY • Health Air pollution harms health and causes thousands of premature • Environmental sustainability deaths every year. Children, older citizens and people with asthma are • Infrastructural security particularly vulnerable, and low-income and ethnic minority groups are also disproportionately affected. Some areas of congested London exceed legal limits making air pollution an invisible public health crisis. Roundabouts are ideally situated dead-spaces which can provide locations to house a solution. Actors HOW • Greater London Authority Councils could work alongside organisations (such as GLNP and and Councils The Healthy Air Campaign) to develop roadside algae installations which • Transport for London not only respond to areas with the most serious pollution levels, but also • Algal technology companies create new spaces of environmental sustainability and community pride, • Local businesses providing jobs and training in dynamic new city ecosystems. -

A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi

A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi by Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire 2006 Tauraco Research Report No. 8 Tauraco Press, Liège, Belgium A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi by Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire 2006 Tauraco Research Report No. 8 Tauraco Press, Liège, Belgium Tauraco Research Report No. 8 (2006) A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi ISBN 2-87225-003-4 Dépôt légal: D/2006/6838/06 Published April 2006 © F. Dowsett-Lemaire All rights reserved. Published by R.J. Dowsett & F. Lemaire, 12 rue Louis Pasteur, Grivegnée, Liège B-4030, Belgium. Other Tauraco Press publications include: The Birds of Malawi 556 pages, 16 colour plates, 625 species distribution maps, Tauraco Press & Aves (Liège, Belgium) Pbk, April 2006, ISBN 2-87225-004-2, £25 A Contribution to the Ornithology of Malawi by Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire CONTENTS An annotated list and life history of the birds of Nyika National Park, Malawi-Zambia ...........................1-64 Notes supplementary to The Birds of Malawi (2006) ..............65-121 Birds of Nyika National Park 1 Tauraco Research Report 8 (2006) An annotated list and life history of the birds of Nyika National Park, Malawi-Zambia by Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire INTRODUCTION The Nyika Plateau is the largest montane complex in south-central Africa, with an area of some 1800 km² above the 1800 m contour – above which montane conditions prevail. The scenery is spectacular, with the upper plateau covered by c. 1000 km² of gently rolling Loudetia-Andropogon grassland, dotted about with small patches of low-canopy forest in hollows. Numerous impeded drainage channels support dambos. These high-altitude Myrica-Hagenia forest patches (at 2250-2450 m) are often no more than 1-2 ha in size, and cover about 2-3% of the central plateau.