Working Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conflict Sensitivity in Education Provision in Karen State Polina Lenkova

Conflict Sensitivity in Education Provision in Karen State Polina Lenkova December 2015 Inside front cover Conflict Sensitivity in Education Provision in Karen State Polina Lenkova December 2015 About the researcher Polina Lenkova is a research fellow at Thabyay Education Foundation. She holds a Master of Arts in International Relations from the School of Advanced International Studies, John Hopkins University, Washington, D.C. About Thabyay Education Foundation Founded in 1996, Thabyay Education Foundation educates, develops, connects and empowers individuals and organizations in Myanmar to become positive, impactful change-makers. We seek to achieve this through knowledge creation, innovative learning and guided skills expansion, as well as by forging connections to networks, information and opportunities. Acknowledgements The author would like to express her gratitude to everyone who participated in and assisted her during this research. Particularly, the author would like to thank the following people and organizations for providing assistance and suggestions during field research: Tim Schroeder, Saw San Myint Kyi, Saw Eh Say, Hsa Thoolei School, Taungalay Monastery, as well as Thabyay Education Foundation staff Hsa Blu Paw, Cleo Praisathitsawat and U Soe Lay. Furthermore, the author also thanks Tim Schroeder, Kim Joliffe and Saw Kapi for report review and feedback. Design and layout: Katherine Gibney | www.accurateyak.carbonmade.com Note on the text All web links in the report’s footnotes were correct and functioning as of 1 December 2015. 4 Conflict Sensitivity in Education Provision in Karen State Contents Acronyms and Glossary 6 Executive Summary 7 1. Introduction: Defining Conflict Sensitivity in Education 10 2. Objectives and Methodology 11 3. -

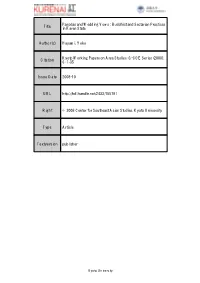

Buddhist and Sectarian Practices in Karen State Author(S)

Pagodas and Wedding Vows : Buddhist and Sectarian Practices Title in Karen State Author(s) Hayami, Yoko Kyoto Working Papers on Area Studies: G-COE Series (2008), Citation 6: 1-35 Issue Date 2008-10 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/155791 Right © 2008 Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Type Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Pagodas and Wedding Vows: Buddhist and Sectarian Practices in Karen State Yoko Hayami Kyoto Working Papers on Area Studies No.8 (G-COE Series 6) October 2008 Pagodas and Wedding Vows: Buddhist and Sectarian Practices in Karen State Yoko Hayami Kyoto Working Papers on Area Studies No.8 JSPS Global COE Program Series 6 In Search of Sustainable Hurnanosphcrc in Asia and Africa October1 2008 Pagodas and Wedding Vows: Buddhist and Sectarian Practices in Karen State* Yoko Hayami** Introduction Mount Zwekabin (Kwekabaun) is a magnificent limestone mass visible from the marshy plains surrounding it, and especially from the Karen State capital Paan which lies to its north (photo 1). It is not only a physical landmark, or an official symbol of Karen State, but is a religious and ritual centerpiece for many of the Karen-speaking people in the area, as well as for some Karen living afar. Atop the mountain is the Upper Yedagone Monastery which is historically the leader among the numerous Karen monasteries on the plains surrounding it. During the hottest months before the rainy season, at one of the innumerable pagodas on the plains at the foot of the mountain called Don Ying Pagoda1, on designated days of the lunar calendar from morning till noon, more than one hundred Karen couples gather clad in their best Karen attire (photo 10). -

Hessler on Cohen, 'Charismatic Monks of Lanna Buddhism'

H-Buddhism Hessler on Cohen, 'Charismatic Monks of Lanna Buddhism' Review published on Tuesday, May 28, 2019 Paul T. Cohen, ed. Charismatic Monks of Lanna Buddhism. Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2017. 272 pp. $27.00 (paper), ISBN 978-87-7694-195-6. Reviewed by Felix Hessler (Leibniz University Hannover / Mote Oo Education, Yangon) Published on H-Buddhism (May, 2019) Commissioned by Thomas Borchert (University of Vermont) Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=53644 The collection of eight articles presented by Paul T. Cohen in Charismatic Monks of Lanna Buddhism gives fascinating insights into a strand of Theravāda Buddhism that has received little scholarly attention until now. At the heart of contemporary Lanna Buddhism, which is mainly practiced in the areas around Chiang Mai (Thailand), the borderland of neighboring Myanmar and, to a lesser degree, in Laos and southern China, lies the work of the ton bun (person of merit), charismatic holy monks. Since many of these monks see themselves in a lineage with the famous Khruba Siwichai (1878-1938) and share several distinctive characteristics, some scholars speak of a "khruba movement." Khruba translates as "venerated teacher." It is not an official title given by governments or the sangha hierarchy, but is given by local communities out of veneration. In the context of Lanna Buddhism and the "khruba movement" it refers to ton bun—monks who are believed to be holy and who share a number of distinct qualities. According to Paul Cohen, one defining feature of the khruba movement is the "paradoxical combination in this holy man tradition of other-worldly asceticism and this-worldly activism” (p. -

Burma's Longest

TRANSNATIONAL I N S T I T U T E B URMA C ENTER N ETHERLANDS Burma’s Longest WAR ANATOMY OF THE KAREN CONFLICT Ashley South 3 Burma’s Longest War - Anatomy of the Karen Conflict Author Ashley South Copy Editor Nick Buxton Design Guido Jelsma, www.guidojelsma.nl Photo credits Hans van den Bogaard (HvdB) Tom Kramer (TK) Free Burma Rangers (FBR). Cover Photo Karen Don Dance (TK) Printing Drukkerij PrimaveraQuint Amsterdam Contact Transnational Institute (TNI) PO Box 14656, 1001 LD Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel: +31-20-6626608 Fax: +31-20-6757176 e-mail: [email protected] www.tni.org/work-area/burma-project Burma Center Netherlands (BCN) PO Box 14563, 1001 LB Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel: +31-20-671 6952 Fax: +31-20-6713513 e-mail: [email protected] www.burmacentrum.nl Ashley South is an independent writer and consultant, specialising in political issues in Burma/Myanmar and Southeast Asia [www.ashleysouth.co.uk]. Acknowledgements The author would like to thank all those who helped with the research, and commented on various drafts of the report. Thanks to Martin Smith, Tom Kramer, Alan Smith, David Eubank, Amy Galetzka, Monique Skidmore, Hazel Laing, Mandy Sadan, Matt Finch, Nils Carstensen, Mary Callahan, Ardeth Thawnghmung, Richard Horsey, Zunetta Liddell, Marie Lall, Paul Keenan and Miles Jury, and to many people in and from Burma, who cannot be acknowledged for security reasons. Thanks as ever to Bellay Htoo and the boys for their love and support. Amsterdam, March 2011 4 Contents Executive Summary 2 Humanitarian Issues 30 MAP 1: Burma -

Individual Enlightenment and Social Responsiblity: on the Sociological Interpretations of the Holy Monk Khruba Boonchum

INDIVIDUAL ENLIGHTENMENT AND SOCIAL RESPONSIBLITY: ON THE SOCIOLOGICAL Interpretations OF THE HOLY MONK KHRUBA BOONCHUM Dayweinda Yeehsai and John Giordano Assumption University, Thailand ABSTRACT This paper will assess some sociological interpretations of Theravada Buddhism and Holy Monks which rely on such concepts as charisma, millenarianism and utopianism. In the past, sociologiests like Weber and Murti misinterpreted Buddhism as focusing upon individual enlightenment rather than the welfare of society. But these interpretations of Theravāda Buddhism overlook that the Buddhist concept of enlightenment has a deep relationship with social development and social responsibilities. Buddhism has a highly developed sociological basis and need to be understood in its own terms. The practice of Buddhist monks should be understood by means of Buddhist sociology. To illustrate this, this paper will discuss the Theravāda Buddhist concept of the ten perfections (pāramī) in general and perfection of morality (sīla-pāramī) in particular. This will also be illustrated by Buddhist tale of Bhuridatta-Jātaka and the case of Spiritual Master, the Most Venerable Khruba Boonchum, Nyanasamvaro. Keywords: Buddhism, Buddhist Sociology, Holy Monks, Khruba Boonchum Prajñā Vihāra Vol. 19 No 2, July - December 2018, 93-115 © 2000 by Assumption University Press 94 Prajñā Vihāra Introduction This paper is an attempt to assess the value of sociological interpretations of Theravada Buddhism through the concepts of charisma, millenarianism and utopianism. In the past, scholars like Max Weber and Murti misinterpreted Buddhism as focusing upon individual enlightenment rather than the welfare of society. For instance, Weber stated, “Salvation is an absolutely personal performance of the self-reliant individual. No one, and particularly no social community, can help him”. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 Background .............................................................................................................................. 2 Political context ........................................................................................................................ 3 The Democratic Kayin Buddhist Organization ........................................................... 3 Attacks by the DKBA and the SLORC on Karen refugees ................................................... 6 Abduction and forcible return ................................................................................................. 6 Incidents prior to February 1995 ............................................................................................ 8 Initial incursions and abductions - early February 1995 ......................................................... 9 Abductions of KNU Officials and camp administrators ...................................................... 10 Abduction of Phado Mahn Yin Sein and Win Sein; possible extrajudicial killing of Jeffrey Win ....................................................................................... 11 Abduction of Sein Tun and Hti Law Paw ............................................................................ 12 Abduction of “Uncle Jolly”.................................................................................................... 13 -

In Pursuit of Morality

In Pursuit of Morality Moral Agency and Everyday Ethics of Plong Karen Buddhists in Southeastern Myanmar Justine Alexandra Chambers A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The Australian National University October 2018 © Copyright by Justine Alexandra Chambers 2018. All Rights Reserved i STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY Except where otherwise indicated, this thesis is my own original work. Justine Chambers 5 October 2018 Department of Anthropology College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University ii ABSTRACT This thesis explores how Buddhist Plong Karen people in Hpa-an, the capital of Karen State, Myanmar pursue morality in what is a time of momentous social, political and cultural change. As one of the rare ethnographic studies to be conducted among Plong Karen people in Myanmar in recent decades, my research problematises existing literature and assumptions about ‘the Karen’. Informed by eighteen months of participant observation in Hpa-an, I examine the multiple ways that Plong Karen Buddhists broker, cultivate, enact, traverse and bound morality. Through an analysis of local social relations and the merit-power nexus, I show that brokering morality is enmeshed in both the complexities of the Buddhist “moral universe” (Walton 2016) and other Karen ethical frameworks that define and make personhood. I examine the Buddhist concept of thila (P. sīla), moral discipline, and how the everyday cultivation of moral “technologies of the self” (Foucault 1997), engenders a form of moral agency and power for elderly Plong Karen men and women of the Hpu Takit sect. Taking the formation of gendered subjectivities during the transitional youth period as a process of “moral becoming” (Mattingly 2014), I demonstrate the ways young women employ moral agency as they test and experiment with multiple modes of everyday ethics and selfhood. -

Maximizing Transport Benefits Through Community Engagement Project

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 46422-002 December 2015 Republic of the Union of Myanmar: Maximizing Transport Benefits through Community Engagement (Financed by the Technical Assistance Special Fund) Prepared by the Mekong Economics, Ltd. and the Adventist Development Relief Agency Myanmar For the Ministry of Construction and the Asian Development Bank This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. Kayin and Mon State Context, Stakeholders and Engagement Kayin and Mon States Context, Stakeholders and Engagement Guidance for the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and implementing partners December 2015 Mekong Economics / ADRA Myanmar 1 Kayin and Mon State Context, Stakeholders and Engagement Table of Contents Acronyms ....................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................... 6 Terminology ......................................................................................... 8 A note on place names and administrative demarcation .................................... 8 Ethnographic overview ............................................................................ 9 Overview of Conflict and peace in Kayin and Mon States ........................... 10 The Peace Process since 2011 .................................................................. 12 Humanitarian impacts: -

Spiritual Protection, Justice, and Religious Tensions in the Karen State.1 Mikael Gravers

A Saint in Command? Spiritual Protection, Justice, and Religious Tensions in the Karen State.1 Mikael Gravers Abstract In 1995, when the Myaing Gyi Ngu Sayadaw, U Thuzana, split the KNU and formed the DKBA, he was considered a stooge of the Myanmar army. However, the monk had a vision and a prophecy of revitalizing a Karen Buddhist land, protect his followers, and uniting all Karens. This article analyses his strategy and events since 1995. It is argued that he organized a theocratic trust net- work and provided protection and justice during the conflict. In recent years his activities have created religious tensions and conflicts. This is related to the general situation in Myanmar where religious identity and nationalism dominates politics. It is argued that religious interventions may create problems for the peace process as well as for democratization and a common law. 1The author conducted fieldwork in Karen State during February and March 2017 together with anthropologist Anders Baltzer Jørgensen, Saw Say Wah and Saw Eh Dah whose assistance was invaluable. The author has visited Myaing Gyi Ngu in 2012, 2013 and 2014. In 2017, the authorities denied us access due to ongoing fighting. In 1996, the author interviewed Karen refugees in Thailand who fled from DKBA. He has also interviewed followers of the monk in Thai- land along the border, as well as in Chiang Mai and Lamphun. Last, but not least, the work on this subject owes a lot to Tim Schroeder who has accompa- nied the author and shared his knowledge. 2 | Gravers စာတမ်းအကျး -

Ceasefires, Governance and Development: the Karen National

Ceasefires, Governance, and Development: The Karen National Union in Times of Change Kim Jolliffe December 2016 Acknowledgements The author would like to thank the many individuals in the Karen National Union, Karen community based organizations, and other Karen armed organizations who contributed their time, knowledge and encouragement to make this study possible. In particular, this work was inspired by the impressive and diverse Karen social service and humanitarian networks that work tirelessly every day to support communities affected by war. Significant parts of this research would not have been possible without support from the Karen Environmental Social Action Network, which works for rural livelihoods and environmental security of indigenous Karen people. This study benefited greatly from the more than two decade’s worth of testimony from rural Karen civilians collected by the Karen Human Rights Group, which remains a crucial and extraordinary resource to any research on these conflicts. This work was improved immeasurably by input from Brian McCartan, Tim Schroeder, Ashley South, Paul Keenan, and Jared Bissinger, which included feedback on drafts and various published and unpublished materials. Encouragement and dialogue with multiple other Myanmar and international researchers and professionals were also highly valuable. This series of papers has been built on the firm foundations of the broader research program initiated and developed by The Asia Foundation’s Matthew Arnold, among other key individuals. It has been made possible by the tireless production, administrative and editorial work of Mim Koletschka, Win Po Po Aung and the rest of their team. About the Author Kim Jolliffe is an independent researcher, writer, analyst and trainer, specializing in security, aid policy, and ethnic politics in Myanmar/Burma. -

REPORT to the FOUNDATION DECEMBER 2004 Shwedagon Pagoda, Yangon Golden Rock, Kyaiktiyo

PEOPLE IN NEED GERHARD-BAUMGARD-STIFTUNG REPORT TO THE FOUNDATION DECEMBER 2004 Shwedagon Pagoda, Yangon Golden Rock, Kyaiktiyo PEOPLE IN NEED – GERHARD-BAUMGARD-STIFTUNG I. MYANMAR A. BACKGROUND You know that after leaving Investment Banking more than 2 years ago - I worked with Medecins Sans Frontieres in Indonesia/West Timor and in Thailand at the border with Burma/Myanmar. End of last year I had enough of international headquarters and international donors who want to micro-manage humanitarian projects from an office desk in a Western capital. I set up my own charitable foundation PEOPLE IN NEED – Gerhard- Baumgard-Stiftung, registered in Germany, and moved to Myanmar (formerly: Burma) to help. Why Myanmar? The “Country where the time stood still”: Asia as it was in the 50ties. The “Land of the Golden Pagodas” is without doubt beautiful and very scenic for tourists who are here on a two-week stint and stay in one of the luxury hotels available for dollars. Like I did a couple of years ago tourists marvel about ox-carts, rotten cars, bamboo huts, kerosene lamps and candles in the evening and turn a blind eye to the dirt, the lack of sanitation and clean water and to the people who search garbage heaps in the markets to find something to eat. But if you are one of the ordinary folks who have to live without electricity and water, without proper housing and medical care, without education and without a decent income to feed your family you would probably have another view. 50 million people live in this country which is bigger than France (or as big as Texas) and most of them live in poverty. -

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRAPHY Abeysekara, Ananda. 2001. The Saffron Army, Violence, Terror(ism): Buddhism, Identity, and Difference in Sri Lanka. Numen 48 (1): 1–46. ABMA. 2018. About the ABMA. All Burma Monks’ Alliance. http://allburma- monksalliance.org Acharya, Amitav, and Barry Buzan. 2010. Conclusion: On the Possibility of a Non-Western International Relations Theory. In Non-Western International Relations Theory. Perspectives on and Beyond Asia, ed. Amitav Acharya and Barry Buzan, 221–238. London/New York: Routledge. Adas, Michael. 1974. The Burma Delta: Economic Development and Social Change on an Asian Rice Frontier, 1852–1941 (e-book). Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. Aeusrivongse, Nidhi. 2004. Understanding the Situation in the South as a ‘Millenarian Revolt’. Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. https://kyotoreview.org/ issue-6/understanding-the-situation-in-the-south-as-a-millenarian-revolt/ AFP. 2018. Myanmar lures Bangladesh Buddhists to Take over Rohingya Land: Officials.Agence France Press, April 2. https://www.bangkokpost.com/news/ world/1439458/ Ahmed, Ibtisam. 2017. The Historical Roots of the Rohingya Conflict.IAPS Dialogue, October 4. https://iapsdialogue.org/2017/10/04/the-historical- roots-of-the-rohingya-crisis/ AJ+. 2014. Myanmar’s Anti-Muslim Monks (YouTube video). November 12. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GtAl9zJ3t-M Allen, Charles. 2013. Ashoka: The Search for India’s Lost Emperor. Paperback ed. London: Abacus. © The Author(s) 2019 271 P. Lehr, Militant Buddhism, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03517-4 272 BIBLIOGRAPHY Almond, Gabriel A., R. Scott Appleby, and Emmanuel Sivan. 2003. Strong Religion: The Rise of Fundamentalisms Around the World. Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press.