The Novel in Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

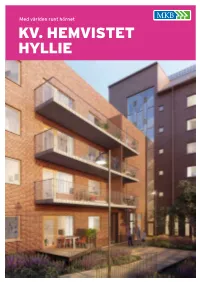

Kv. Hemvistet Hyllie a B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V X

Med världen runt hörnet KV. HEMVISTET HYLLIE A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V X en 1 E äg sv H lm an o e ckh s s to I p e S nr l. n e s Ri n Klipperg g n vä stkustväge SEGEVÅNG Vä ge v VÄSTRA n parksg kust HAMNEN Sege- Ö äst stra an V sgat arv F 2 S ä St V lad k e s g g- pp Jun tockholmsvägen a S ta mansg s n g Malmö C KIRSEBERGS- N a Hornsgat ndavägen t an a Lu V STADEN n ÖSTER- attenve llgatan rksvägen ra Va rgatan Ö F VÄRN gen Nor Öste örst Horns ellsvä a Citad ds Stora B g ulltoftaväge g n Slottsga GAMLA STADEN Drottninggatan 3 an ta Stora Nygatan gat n s RÖRSJÖ- ing S RIBERS- allerupsväg en STADEN g BORG gatan JOHANNESLUST svä Fören amn en lust Limh n n KATRINELUND torgatan Ka e S tr Johannes g n ine lu ä entsgata ndsg Regem n lväge v be S g Mariedalsv ata al FRIDHEM g o Marietorps allé s le in N ru n C g p R e n Kö ar nn ni s penham g ö e e 4 RÖNNE- R holm vä ä l ra sv För armvägen g stvägen v HOLM G Öst en F nsväge ttre e ust SORGENFRI u a kslu afs r Y n v RÅDMANS- Eri Sorgenfriväge en lle v äg VÅNGEN Amir Öst n Pilda e sväg B n a Köpenhamnsvägen ta ls n ham a g E6 atan Sa Lim m sg llerupsv Station g ägen Sal msv Triangeln r leru E20 DAMMFRI e ps C B vägen ä arl E22 g Gu MÖLLEVÅNGEN MELLANHEDEN en sta John fs 5 GAMLA Geijersgatan vä Ericss g Klåger LIMHAMN ANNELUND gen ons vä Ami n S belvägen r u ge g på alsg p svä rv No ata svä amn tan n ägsg n h a e g m edalsvä e Li ég g NORRA n ag n ä SÖDER- n Lin SOFIELUND K Vid ev opparb TÖRN- Klå u VÄRN ergsg ger Stadio ROSEN up ev tman s n vägen n n ta g a en a a Bell t L Linnégatan -

Praktik Och Teori Nr 3/2002 • Malmö

MALMÖ • PRAKTIK OCH TEORI NR 3/2002 MALMÖ HÖGSKOLA Praktik och teori 3/2002 • Malmö ISSN 1104-6570 1 www.lut.mah.se Våra hemsidor på nätet och den tryckta skriften kompletterar varandra. På nätet hittar du konferenser, seminarier och lik- nande dagsaktuella saker. Kalendariet uppdateras ständigt. Praktik och teori och olika skrifter finns också på nätet i pdf- format. Dessa kan läsas med Acrobat Reader som kan hämtas hem gratis på nätet. Prenumerera på pappersutgåva För prenumeration kontakta Anette Persson, Gemensam administration och service (GAS), tel 040-665 80 69, fax 040-665 82 25 [email protected] 2 Innehåll Redaktionen Förord 5 Mikael Stigendal Bryr sig Malmö högskola om malmöborna? 8 Helena Smitt Ut i samhället för att förstå det – självfallet också högskolans uppgift Intervju med Mikael Stigendal 16 Kent Andersson Malmö högskola kan inte slå sig till ro 20 Margareta Popoola Så konstrueras Malmös identitet 26 Cesar Vargas Min del i Malmö och Högskolan 47 Mikael Mattesson Vad har Malmö högskola och kulturlivet ihop? 52 Daniel Tjäder Malmö svänger men skulle kunna svänga ännu mer 56 Gunilla Konradsson-Mortin och Eva Olsson Stans bästa dateingplace!!! Är det så studenterna ser på Stadsbiblioteket eller … 64 Johan Book Låt studenterna knyta an till framtida arbetsgivare under utbildningstiden på ett helt annat sätt än idag 70 Jan-Olof Jönsson Stadsbyggnadsvisionen om högskolan som interagerande med Malmö 77 Birthe Pedersen En självklarhet i staden 84 Lars Berggren, Mats Greiff, Roger Johansson Så knyts Malmös invånare ihop med högskolan 92 Annika Karlsson Med andra ögon 110 3 Förord almö – kan man säga det så enkelt. -

Informationsblad Holma Torg

Holmas nya vardagsrum HOLMA TORG Holmas nya vardagsrum Holma genomgår just nu en omfattande förnyelse och förvandling. Här ska modern bebyggelse och ett nytt levande torg skapa nya spännande möten mellan människor från hela Malmö. Utbyggnaden av Hyllie med nya bostäder, kontor, service tillsammans med goda kommunikationsmöjligheter innebär att Holma flyttar fram sin position och blir en del av Malmös nya framsida. Läget mitt emellan innerstaden och Hyllie har många fördelar. Det finns gott om kommunikations- möjligheter med bil och buss och i Kroksbäcksparken kommer en cykelboulevard anläggas. Det är lika nära till fotboll på Swedbank Stadion och ishockey i Malmö Arena som till köpcentren Mobilia och Emporia. Holma blir dessutom granne med nya Hylliebadet. Den omedelbara närheten till det gröna är en av de många fina kvaliteter som kännetecknar Holma. De prunkande och ombonade gårdarna vittnar om att det gröna har en central roll och MKB:s självförvaltning har också sitt ursprung här. Tillsammans med Hyllierankans odlingslotter omsluter Kroksbäcksparken hela området och ger Holma dess speciella gröna karaktär. Den närliggande Kroksbäcksparken är Malmös tredje största park och kännetecknas främst av sina sju kullar. Här kan man njuta av en fantastisk utsikt, springa tuffa intervaller eller åka pulka. I parken finns världens första puckelfotbollsplan där man aldrig riktigt vet var bollen studsar. Den fina temalekplatsen ”Äventyr” lockar äventyrslystna besökare från hela Malmö med utmaningar för både barn och vuxna. A B C D E F G H I J K -

Om Släktgården Hindby Nr 6 Som Blev Stadsdelen Eriksfält

O M S L Ä K T G Å R D E N H I N D B Y N R 6 S O M B L E V S T A D S D E L E N E R I K S F Ä L T Ingemar Wickström December 2010 (rev. mars -11, april -12) (I denna internetversion har vissa uppgifter om nu levande personer m.m. utelämnats) Av alla de gårdar som vår släkt under århundradena brukat finns en del som med större skäl än andra kan kallas släktgårdar. En av dessa är gården Hindby nr 6 i Fosie socken, som på ett eller annat sätt haft anknytning till vår släkt i 300 år. Till Hindby by kom omkring år 1680 bröderna Per och Lars Rasmusson och slog sig ned som brukare av kronorusthållen Hindby nr 1 (Per) och Hindby nr nr 2 (Lars). De var söner till bonden Rasmus Larsson på Fjärdingslöv nr 4 i Glostorps socken, om vilken det sades när han 1698 dog: "ehn 78 åhrs gl: mand: hadde uthi långl tidh booet i Fielanslöf: lefwat i Ectenskap 52 åhr, ehn fader till 11 barn,.....ehn myket skröpl: Menniskja, war i huse hos sin doter". Lars Rasmussons äldste son, Per Larsson, dyker i början av 1700- talet upp på Hindby nr 6, som han sedan brukade till sin död 1755. Per hade bland sina 15 barn döttrarna Marna och Margareta, av vilka Marna skall närmare beröras nedan och Margareta var mormors mormor till vår släkts Boel Mårtensdotter Lindström, gift med den nedannämnde Jöns Persson på Fosie nr 5. -

27 September

Här finns drop-in-vaccination nära dig. Tärnöskolan Helikopter ygplats VÄSTRA 6 FRIHAMNEN Segeåparken HAMNEN Malmö högskola Segevångs- skolan SEGEMÖLLA Turning Torso SEGEVÅNG Segevångs- INRE gården Östra HAMNEN Sjukhuset Kirsebergs- Central- GAMLA skolan station MALMÖ STADEN Beijers park VALDEMARSRO Drottning- KIRSEBERG torget World Maritime University Stor- Bulltofta- Öresundsparken torget skolan Tekniskt museum Malmö Österports- muséer 15 skolan RÖRSJÖ Kirsebergs STADEN ishall Marie- Kungsparken Gustav Värnhems- dals- Adolfs Länsstyrelsen skolan Rörsjö- 5 BULLTOFTA parken Gamla torg skolan Ellstorps- JOHANNES Begravnings- KATRINELUND parken 13 Slotts- platsen Latin- LUST Mölledals- Stads- skolan Mariedals parken biblioteket Värnhems skolan FRIDHEM Idrottsplats S:t Pauli norra Sjukhus 7 kyrkogård Risebergaparken DAVIDSHALL S:t Petri Mellersta skola Davids- Borgar- halls förstads- Rise RIBERSBORG skolan torg skolan VÄRNHEM be Bulltofta skola 2 Idrottsplats rekreations- Stads- S:t Pauli område Limhamns- huset fältet mellersta SORGENFRI RISEBERGA Rönne- kyrkogård Stads- HÅKANSTORP holms- Mont- S:t Pauli parken teatern bijou- södra Videdals- Rönneholms skolan 9 BELLEVUE skolan Idrottsplats Konsthall Sorgenfri- kyrkogård trakplats Hyllie- RÖNNEHOLM skolan kroken FÅGELBACKEN Amiralen Limhamns Slotts- Hamn EMILSTORP stadens Pil- Folkets Dammfri- Kronborgs- da skola skolan skolan mms- Park Östra Skola Mellan- skolan Kyrkogården hedsparken DAMMFRI Stenkula- Halltorps- Tandl.- 14 skolan parken NYA Mellanheds- KRONBORG högsk. SÖDER G:LA Vikinga- -

Cykelåret 2016 Malmö

Cykelåret 2016 Malmö 1 Innehåll 3 4 5 Alla Malmöbor har Malmö ska bli en Mål rätt att cykla erkänd cykelstad 10 7 6 Snabbfakta! Nya Kort om cykelvägar Malmö by Bike 12 14 19 Cykelförbättringar Nya Cykling för alla cykelöverfarter 22 21 Cykeltrafikökning Kommunikation & dialog 2 Alla Malmöbor har rätt att cykla Malmö är en cykelstad. Här cyklar vi överallt, hela tiden, året runt. Vi cyklar för att det är enkelt och snabbt. Till och med på vintern! Visionen för cykelstaden Malmö är att Alla Malmöbor har rätt att cykla. Man ska känna sig säker, både när man cyklar och när man har parkerat sin cykel. Vi vill att alla ska kunna cykla. Vi arbetar för att alla ska kunna känna vinden i ansiktet och uppleva denna vackra stad – på det bästa sättet att färdas genom den. 3 Malmö ska bli en erkänd cykelstad Ambitionen är att vara en internationellt erkänd cykelstad och att det ska vara enkelt och säkert för alla att cykla i Malmö. Cykeln ska vara ett självklart val och tillsammans med gång- och kollektivtrafik vara normen i staden. Cykelplaneringen är en central del av Malmö stads arbete för en hållbar och attraktiv stadsmiljö. Det ska vara lätt att göra rätt! Kommunikation Cykelvägnätet Kampanjer för ökad och säker Cykelbanor, cykelöverfarter, cykling, malmo.se/cykla, vinterväghållning mm. facebook.com/cykligamalmo mm. Service och tjänster Mobility management Cykelparkering, hyrcykelsystem, Cykelfrämjande erbjudanden så som cykelpumpar mm. Cykling utan ålder, cykelskolor och utlåning av elcyklar mm. 4 Häng med på färden! Mer att läsa Att cykla är bra för nästan allt. -

Program För Hundrastområden

GATUKONTORET Program för Hundrastområden 2010.06.02 Foto: Märika Bark, Agneta Sallhed Canneroth, Kajsa Karlström, Inga-Lill Öhlin, Emma Jonasson, Viveca Byhr Lindén, Emma Ekdahl. Foto från Whitewater Dog Park Illustrationer: Märika Bark, Emma Ekdahl Diagram: Emma Ekdahl, Anna Kanschat Innehåll Inledning 4 Hundar i andra länder 7 Hundrastområden 8 Här bor flest hundar 9 Kunskap och inspiration 10 Lokaldebatt och allmänhetens önskemål 12 Riktlinjer för utformning 16 Exempel på hundrastgård 20 Tillgängliga hundrastplatser 21 Målsättning 22 Källor 23 Medverkande ARBETSGRUPP Märika Bark, Emma Ekdahl, Birgitta Hjertberg, Anna Kanschat, Karin Sallby- Isaksson, Maria Sundell-Isling, Tobias Starck och Inga-Lill Ölin. STYRGRUPP Agneta Sallhed Canneroth REFERENSGRUPP Arne Mattsson, Eva Lundqvist och Anders Svensson 3 GATUKONTORET • PROGRAMMET FÖR HUNDRASTOMRÅDEN 2009.08.24 Inledning Det finns fyrtiotvå hundrastgårdar och åtta hundrastplatser runt om i Malmö. Hundrastgård är en inhägnad yta medan hundrastplatsen saknar stängsel och är ett större område. Samlingsnamnet är hundrastområde. Hundrastområden är inte bara en plats där hunden rastas utan även en mö- tesplats för hundarna och deras ägare. Med rätt innehåll blir rastområdet en plats för aktivitet och träning. Vid en inventering av alla Malmös hundrastområden under sommaren 2008 konstaterades både bristområden och behov av upprustning av befintliga hundrastgårdar. Malmö stad jobbar med att öka tryggheten i staden. Hundägarna är en grupp som är ute och rastar sina hundar även under dygnets mörka timmar och i alla väder. Därmed befolkas parker och gångstråk och bidrar till ökad trygghet. I centrala Malmö är det koppeltvång vilket innebär att man inte får släppa sin hund var man vill. Det finns förslag på att koppeltvånget också ska gälla detaljplanelagt område i hela Malmö. -

Den Delade Staden Malmö

Institutionen för Kulturgeografi och Ekonomisk geografi, Lunds Universitet Mathias Wallin SGEK01 HT 2010 Den delade staden Malmö En kvantitativ fallstudie av den socioekonomiska segregationens utveckling i Malmö 1992-2006 och huruvida denna har påverkats av förändringar på bostadsmarknaden Innehållsförteckning 1. Inledning 1 1.1 Bakgrund till studien 1 1.2 Disposition 2 2. Problemformulering och avgränsning 4 2.1 Problemformulering 4 2.2 Avgränsningar 4 2.2.1 Geografiska avgränsningar 4 2.2.2 Tidsmässiga avgränsningar 5 3. Teori 6 3.1 Begreppen segregation och integration 6 3.2 Social polarisering 8 3.3 Effekter på polarisering av förändring i bostadsbeståndets upplåtelseformer 9 3.3.1 ”Right to buy” – exemplet Storbritannien 9 3.3.2 Svenska förhållanden 11 3.4 Sammanfattning teori 11 4. Metod 13 4.1 Operationalisering av begrepp 13 4.1.1 Socioekonomisk segregation och social polarisering 13 4.2 Socioekonomiskt index 14 4.2.1 Indexering med hjälp av z-värden 14 4.2.2 Indexering medelst faktoranalys 15 4.3 Bostadsbeståndets förändrade upplåtelseformer 16 4.4 GIS-analys 17 4.5 Spatial autokorrelation och klustring med Local Morans I 17 4.6 Korrelation och kausalitet 17 5. Material 19 5.1 Empiri 19 5.1.1 Problem med det empiriska materialet 21 5.1.2 Förändrade variabler 22 5.1.3 Användande av sekundärdata 22 5.2 Teoretiskt material 23 5.3 Metodologiskt material 23 6. Analys 24 6.1 Inledning 24 6.2 Den sociala polariseringens utveckling över tid 25 6.3 Den sociala polariseringen i det urbana rummet, 1992-2006 26 6.3.1 1992 27 6.3.2 2006 29 6.3.3 Förändring i socioekonomiskt index mellan 1992 och 2006 30 6.4 Spatial autokorrelation i förändringen av socioekonomiskt index 32 6.5 Socioekonomiskt index i förhållande till bostadsbeståndets upplåtelseformer 35 i 6.6 Förändringen över tid i socioekonomiskt index i förhållande till förändringen i bostadsbeståndets upplåtelseformer 36 7. -

Vägvisningsplan För Malmö Stad 2008

VÄGVISNINGSPLAN FÖR MALMÖ STAD 2008 Slutversion 2008-05-16 Antagen 2008-05-29 Reviderad Förord Vägvisningsplanen är framtagen av trafikavdelningens trafikregleringsenhet, Gatukontoret Malmö. Planen innehåller de förhållningssätt som gäller vid vägvisning i Malmö kommun och utgör underlaget för arbetet med vägvisningen. I vägvisningsplanen finns även de riktlinjer som gäller vid upprättande av vägvisning. Själva underlaget för befintlig vägvisning i Malmö kommun finns i digital miljö där både vägmärke och linjedragningar återfinns. Malmö Maj 2008 Rickard Johansson Kontaktuppgifter Telefon 040-34 10 00 Adress Gatukontoret Malmö Trafikregleringsenheten 205 80 Malmö Innehållsförteckning: BAKGRUND .......................................................................................5 ALLMÄNT ...........................................................................................6 BYTE AV BEFINTLIG VÄGVISNING ...........................................................................6 LAGAR, FÖRORDNINGAR MM .....................................................7 Vägmärkesförordningen, VMF (2007:90).....................................................................7 Väglagen, Vägl (1971:948).............................................................................................7 Vägkungörelse, VägK (1971:954).................................................................................7 Vägverketsföreskrifter, VVFS 2007:305.......................................................................7 VÄGVERKETS PUBLIKATIONER .................................................7 -

Skanes Historia 1

1 Sven Rosborn Den skånska historien Före skrivkonsten 3 Tryck: Team Offset & Media Papper: 130 g Silverblade art Malmö 1999 ISBN: 91-973777-0-8 Bilden på titelsidan: Framgrävning av skelett från vikingatiden från gravfältet vid Grötehögen i Fosieområdet. Foto Göran Winge. Då inget annat anges kommer fotografierna i denna bok från författarens eget bildarkiv. Copyright Sven Rosborn 1999. 4 Innehåll Inledning Bronsets tid (1.800 f.Kr. – 500 f.Kr.) Vad är tid? Forntidssiluetter mot horisonten 83 Högarnas folk 89 Att datera forntiden 9 Stridsvagnarna i Göingeskogen 94 Bilder från bronsåldern 103 De äldsta spåren Bronset och vattnet 111 (10.000 f.Kr. – 4.000 f.Kr.) Med lågorna till dödsriket 123 Det spökar vid fornminnena 127 En renjägarfamiljs lägerplats 13 Ett annorlunda landskap 18 Smidessläggans tidevarv På den skånske jägarens boplats 20 (500 f.Kr. – 1000 e.Kr.) De som började odla jorden Om järn och romare 137 (4.000 f.Kr. – 1.800 f.Kr.) En krigisk tid 141 Om tron 146 Från jägare till bonde 33 De döda i mossarna 149 Hindby mosse 38 Men gravarna finns kvar 153 De slipade flintyxorna 41 Och de hade tak över huvudet 161 Bönderna reser stenmonument 49 Uppåkra 169 Skåningen börjar markera revir 58 Vikingar i Fosie 174 Samtal med en död kvinna 63 Gamla skånska hus 74 5 Förord Föreliggande bok är ett gott exempel på samar- svenskan, Arbetet och Skånska Dagbladet - som bete på olika plan. Fotevikens Museum har sedan bidragit med olika tidningsartiklar. länge haft planer på att komma ut med ett antal böcker om Skånes äldre historia; Fosie stadsdels- På Malmö Museum och på Stadsantikvariska förvaltning har samtidigt haft en önskan att de många avdelningen vill jag framföra mitt tack till Ingmar och viktiga utgrävningar som gjordes i området un- Billberg och Catharina Ödman som hjälpt mig med der 1960-1970-talen bättre kommer till allmänhe- att uppdatera vissa fynd. -

Aktualitetsprövning Och Översyn Översiktsplan Malmö.Pdf

ÖVERSIKTSPLAN FÖR MALMÖ Aktualitetsprövning och översyn 2016–17 Underlag för samråd HAMNEN B U R L Ö V S K O M M U N en äg sv m ol kh oc St S T A F F A N S T O R P S KIRSEBERG K O M M U N INNERSTADEN ROSENGÅRD HUSIE LIMHAMN n e g ä v g n i R e r n I n e g ä v s g r o b lle e r HYLLIE T FOSIE Ysta dvä gen S V E D A L A K O M M U N BUNKEFLOSTRAND n väge Yttre Ring n n e e OXIE g g ä ä v v s s g g r r o o b b e e MARKANVÄNDNING l l l l e e r r T T Existerande blandad stadsbebyggelse KLAGSHAMN Ny blandad stadsbebyggelse Existerande verksamhetsområden TYGELSJÖ Nya verksamhetsområden Odlingslandskap Existerande park och natur Ny park och natur Begravningspla tser V E L L I N G E K O M M U N Särskilda fritidsområden 23 december 2016, 12:14 em 23 december Samrådshandling 1 Innehåll Gällande översiktsplan Förord . 3 Antagen av kommunfullmäktige 22 maj 2014 Sammanfattning . 4 Översiktsplanen är i huvdsak aktuell . 6 Motiv och förutsättningar för översynen . 8 Översynens omfattning . 14 Förslag till nya bostadspolitiska mål . 20 Pågående planeringsprocesser . 24 planstrategi kartverktyg Hållbarhetsbedömning. 28 www.malmo.se/op www.malmo.se/op/karta Organisation och medverkande . 30 Samrådsprocess och tidsplan Samrådet behandlar översynens inriktning – inte färdiga Samrådet pågår till och med 24 mars 2017. -

Exploring Backgrounds for Food Waste in Schools and Kindergartens

UPTEC W 17 021 Examensarbete 30 hp Juni 2017 Exploring backgrounds for food waste in schools and kindergartens Identification and quantification of factors influencing plate and serving waste Hjördis Steen ABSTRACT Exploring backgrounds for food waste in schools and kindergartens – Identification and quantification of factors influencing plate and serving waste Hjördis Steen Although food waste is known to have a negative impact on the environment, little research about the causes for food waste in school and kindergarten kitchens has been made. In order to identify factors with a significant influence on food waste in schools and kindergartens, divided into plate and serving waste, correlation analysis was performed on quantitative factors. Among the factors that were analyzed, children’s age (n=35, p<0.001, Kendall’s rank correlation tau=0.44), the number of semesters with food waste measurements (n=151, p<0.05, Kendall’s rank correlation tau=0.15) and portion size as an indicator for overproduction (n=97, p<0.01, Spearman’s rank correlation rho=0.28) were significantly increasing plate waste. Serving waste was significantly increased by portion size (n=97, p<0.0001, Spearman’s rank correlation rho=0.42) and was generally higher in satellite units than in production units (n=142, p<0.05, Pearson’s product-moment correlation r=0.19). Multiple linear regression models were developed to quantify the factors’ impact on plate, serving and total waste. While possible causes for serving waste should be further researched, the model for plate waste explained over 70 % of the variation in plate waste in schools and kindergartens.