Contraceptive Choices for Women with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparing the Effects of Combined Oral Contraceptives Containing Progestins with Low Androgenic and Antiandrogenic Activities on the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis In

JMIR RESEARCH PROTOCOLS Amiri et al Review Comparing the Effects of Combined Oral Contraceptives Containing Progestins With Low Androgenic and Antiandrogenic Activities on the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis in Patients With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Mina Amiri1,2, PhD, Postdoc; Fahimeh Ramezani Tehrani2, MD; Fatemeh Nahidi3, PhD; Ali Kabir4, MD, MPH, PhD; Fereidoun Azizi5, MD 1Students Research Committee, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Islamic Republic Of Iran 2Reproductive Endocrinology Research Center, Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Islamic Republic Of Iran 3School of Nursing and Midwifery, Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Islamic Republic Of Iran 4Minimally Invasive Surgery Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Islamic Republic Of Iran 5Endocrine Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Islamic Republic Of Iran Corresponding Author: Fahimeh Ramezani Tehrani, MD Reproductive Endocrinology Research Center Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences 24 Parvaneh Yaman Street, Velenjak, PO Box 19395-4763 Tehran, 1985717413 Islamic Republic Of Iran Phone: 98 21 22432500 Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: Different products of combined oral contraceptives (COCs) can improve clinical and biochemical findings in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) through suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. Objective: This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to compare the effects of COCs containing progestins with low androgenic and antiandrogenic activities on the HPG axis in patients with PCOS. -

Malta Medicines List April 08

Defined Daily Doses Pharmacological Dispensing Active Ingredients Trade Name Dosage strength Dosage form ATC Code Comments (WHO) Classification Class Glucobay 50 50mg Alpha Glucosidase Inhibitor - Blood Acarbose Tablet 300mg A10BF01 PoM Glucose Lowering Glucobay 100 100mg Medicine Rantudil® Forte 60mg Capsule hard Anti-inflammatory and Acemetacine 0.12g anti rheumatic, non M01AB11 PoM steroidal Rantudil® Retard 90mg Slow release capsule Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitor - Acetazolamide Diamox 250mg Tablet 750mg S01EC01 PoM Antiglaucoma Preparation Parasympatho- Powder and solvent for solution for mimetic - Acetylcholine Chloride Miovisin® 10mg/ml Refer to PIL S01EB09 PoM eye irrigation Antiglaucoma Preparation Acetylcysteine 200mg/ml Concentrate for solution for Acetylcysteine 200mg/ml Refer to PIL Antidote PoM Injection injection V03AB23 Zovirax™ Suspension 200mg/5ml Oral suspension Aciclovir Medovir 200 200mg Tablet Virucid 200 Zovirax® 200mg Dispersible film-coated tablets 4g Antiviral J05AB01 PoM Zovirax® 800mg Aciclovir Medovir 800 800mg Tablet Aciclovir Virucid 800 Virucid 400 400mg Tablet Aciclovir Merck 250mg Powder for solution for inj Immunovir® Zovirax® Cream PoM PoM Numark Cold Sore Cream 5% w/w (5g/100g)Cream Refer to PIL Antiviral D06BB03 Vitasorb Cold Sore OTC Cream Medovir PoM Neotigason® 10mg Acitretin Capsule 35mg Retinoid - Antipsoriatic D05BB02 PoM Neotigason® 25mg Acrivastine Benadryl® Allergy Relief 8mg Capsule 24mg Antihistamine R06AX18 OTC Carbomix 81.3%w/w Granules for oral suspension Antidiarrhoeal and Activated Charcoal -

Rominder P.S. Suri, Phd, PE Robert F. Chimchirian & Sandhya Meduri Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering Villa

Emerging Contaminants and Water Supply – Speaker Abstracts Emerging Contaminants and Water Supply – Speaker Abstracts PRESENCE OF ESTROGEN HORMONES AND ANTIBIOTICS IN detection limits for all 12 estrogen compounds ranged from 0.1 ng L-1 to THE ENVIRONMENT 10 ng L-1 using a sample size of 1 L. Eight antibiotics and venlaflaxine Rominder P.S. Suri, PhD, PE were detected in the effluent with concentrations that ranged from 50 to Robert F. Chimchirian & Sandhya Meduri 2,930 ng L-1. Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering Twenty-one streams in Chester County, southeast Pennsylvania, were Villanova University, Villanova PA 19085 also sampled for aqueous concentrations of the above hormones and 610-519-7631 [email protected] antibiotics. Chester County represents a very diverse land use. In addition to concentrated urban developments, there are many In recent years, the detection of trace amount of pharmaceutically active agricultural farms (dairy, cattle, hog, poultry, and mushroom). The compounds (PACs) in the surface water has gained widespread watershed is comprised of about 280,000 acres that eventually drain into attention. The presence of the PACs in the natural water systems causes the Chesapeake Bay via the Susquehanna River. The results showed that ecological problems and possible adverse effects to humans. Two classes there was at least one estrogen detected in every stream sampled and six of PACs, estrogen hormones and antibiotics make their way into the estrogens were detected at three different locations. The most abundant surface waters through effluents from wastewater treatment plants and PAC was estrone, which was detected in all but one stream, with areas where animal manure and biosolids are land applied, amongst concentrations as high as 2.4 ng L-1. -

Ultra-Low-Dose Oral Contraceptive Pill: a New Approach to a Conventional Requirement

International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology Ahuja M et al. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Feb;6(2):364-370 www.ijrcog.org pISSN 2320-1770 | eISSN 2320-1789 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20170006 Review Article Ultra-low-dose oral contraceptive pill: a new approach to a conventional requirement Meenakshi Ahuja1, Pramod Pujari2* 1Senior Consultant Obstetrician and Gynecologist, Max Super Specialty Hospital, Saket, New Delhi, India 2Medical Advisor, Pfizer limited, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India Received: 05 December 2016 Accepted: 17 December 2016 *Correspondence: Dr. Pramod Pujari, E-mail: [email protected] Copyright: © the author(s), publisher and licensee Medip Academy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Combined oral contraceptives (COCs) offer a convenient, safe, effective, and reversible method of contraception. However, their use is limited by side effects. Several strategies have been suggested to make COC use more acceptable among women. Reduction in the dose of estrogen is a commonly accepted approach to reduce the side effects of COC. Use of newer generation of progestins, such as gestodene, reduces the androgenic side effects generally associated with progestogens. Furthermore, reduction in hormone-free interval, as a 24/4 regimen, can reduce the risk of escape ovulation (hence preventing contraceptive failure) and breakthrough bleeding. It also reduces hormonal fluctuations, thereby reducing the withdrawal symptoms. A COC with gestodene 60 µg and ethinylestradiol (EE) 15 µg offers the lowest hormonal dose in 24/4 treatment regimen. -

Removal of Emerging Contaminants from Aqueous Solutions by Using Polymeric Resins

Removal of Emerging Contaminants from Aqueous Solutions by Using Polymeric Resins _____________________________________________________________________ A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _____________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER of SCIENCE in ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING _____________________________________________________________________ By Dan Liu May, 2011 Thesis Approval(s): ____________________ Thesis advisor: Dr. Rominder Suri, Ph.D., P.E. Civil & Environmental Engineering Dr. Tony Singh, Ph.D. Civil & Environmental Engineering Dr. Judy (Huichun) Zhang, Ph.D. Civil & Environmental Engineering ABSTRACT The emerging contaminants (ECs) such as estrogen hormones, perfluorinated compounds (PFCs), bisphenol A (BPA) and 1, 4-dioxane have been detected in natural water bodies at a noticeable level worldwide. The presence of ECs in the aquatic environment can pose potential threats to aquatic organisms as well as human world. Ion-exchange is a highly efficient technology for the removal of heavy metal ions and natural organic materials (NOMs) due to the nature of exchanging similar charged ions. However, this technology has not been explored for removing ECs. In this study, four categories of ECs: estrogen hormones (12), perfluorinated compounds (10), bisphenol A and 1, 4-dioxane were used as model contaminants. The adsorption of each category of ECs onto various types of polymeric resins (MN100, MN200, A530E, A532E and C115) was investigated. The removal of ECs was tested under batch and column mode. The effects of pH, resin dosage, and contact time on the removal of ECs were studied in batch mode; isotherm and kinetics models were applied to fit the experimental data. Column experiments were conducted to verify the practicability of the polymeric resins. -

Study Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

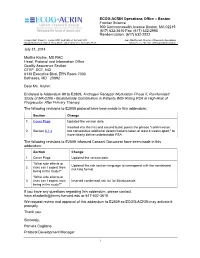

ECOG-ACRIN Operations Office – Boston Frontier Science 900 Commonwealth Avenue Boston, MA 02215 (617) 632-3610 Fax: (617) 632-2990 Randomization: (617) 632-2022 Group Chair: Robert L. Comis, M.D. and Mitchell Schnall, M.D. Jean MacDonald, Director of Research Operations Group Statistician: Robert Gray, Ph.D. and Constantine Gatsonis, Ph.D. Mary Steele, Director of Group Administration July 31, 2014 Martha Kruhm, MS RAC Head, Protocol and Information Office Quality Assurance Section CTEP, DCT, NCI 6130 Executive Blvd, EPN Room 7000 Bethesda, MD 20892 Dear Ms. Kruhm: Enclosed is Addendum #9 to E2809, Androgen Receptor Modulation Phase II, Randomized Study of MK-2206 - Bicalutamide Combination in Patients With Rising PSA at High-Risk of Progression After Primary Therapy. The following revisions to E2809 protocol have been made in this addendum: Section Change 1. Cover Page Updated the version date. Inserted into the first and second bullet points the phrase "confirmed on 2. Section 6.1.4 two consecutive additional determinations taken at least 4 weeks apart," to more clearly define undetectable PSA. The following revisions to E2809 Informed Consent Document have been made in this addendum: Section Change 1. Cover Page Updated the version date. "What side effects or Updated the risk section language to correspond with the condensed 2. risks can I expect from risk lists format. being in the study?" "What side effects or 3. risks can I expect from Inserted condensed risk list for Bicalutamide. being in the study?" If you have any questions regarding this addendum, please contact [email protected] or 617-632-3610. -

Androgens in Women: Hormone-Modulating Therapies For

Androgens in women Hormone-modulating therapies for skin disease Sarah Azarchi, BS,a Amanda Bienenfeld, BA,a Kristen Lo Sicco, MD,b ShariMarchbein,MD,b Jerry Shapiro, MD,b and Arielle R. Nagler, MDb New York, New York Learning objectives After completing this learning activity, participants should be able to list, categorize, and explain the mechanisms of action, safety considerations, and contraindications of these androgen-modulating therapies; identify the hormone-modulating therapies used to treat acne, hirsutism, and androgenetic alopecia; and describe the evidence to support the efficacy of these therapies in the treatment of acne, hirsutism, and androgenetic alopecia. Disclosures Editors The editors involved with this CME activity and all content validation/peer reviewers of the journal-based CME activity have reported no relevant financial relationships with commercial interest(s). Authors The authors involved with this journal-based CME activity have reported no relevant financial relationships with commercial interest(s). Dr Shapiro is a stockholder in Replicel Life Sciences and has been a consultant for Aclaris, Samumed, Incyte, Bioniz, keeps.com, Applied Biology, and Pfizer. Planners The planners involved with this journal-based CME activity have reported no relevant financial relationships with commercial interest(s). The editorial and education staff involved with this journal-based CME activity have reported no relevant financial relationships with commercial interest(s). Androgen-mediated cutaneous disorders (AMCDs) in women, including acne, hirsutism, and female pattern hair loss, can be treated with hormone-modulating therapies. In the second article in this Continuing Medical Education series, we discuss the hormone-modulating therapies available to dermatologists for the treatment of AMCDs, including combined oral contraceptives, spironolactone, finasteride, dutasteride, and flutamide. -

Annex 2. Preparations of Oestrogens, Progestogens and Combinations of Oestrogens and Progestogens That Are Or Have Been Used As

Annex 2. Preparations of oestrogens, progestogens and combinations of oestrogens and progestogens that are or have been used as hormonal contraceptives and for post-menopausal hormonal therapy, with known trade names Table 1. Some combinations of oestrogens and progestogens used in oral contraceptives, with known trade names Combination Trade names Oestrogen Dose Progestogen Dose (μg) (mg) Ethinyloestradiol Biphasic 50 Chlormadinone acetate 1/2 Neo-Eunomin Monophasic 35 Cyproterone acetate 2 Diane, Diane-35, Diane-Mite, Diane Nova, Dianette, Gynofen 35 Monophasic 20 Desogestrel 0.15 Cycléane-20, Lovelle, Marvelon 20, Mercilon, Microdosis, Myralon, Securgin, Segurin ANNEX 2 Monophasic 30 Desogestrel 0.15 Cycléane-30, Desogen, Desolett, Frilavon, Marvelon, Marvelon 30, Marviol, Microdiol, Novelon, Ortho-Cept, Planum, Practil, Prevenon, Varnoline Biphasic 40/30 Desogestrel 0.025/0.125 Gracial Biphasic 50 Desogestrel 0/0.125 Ovidol, Oviol Triphasic 35/30 Desogestrel 0.05/0.1/0.15 Trimiron Monophasic 30 Dienogest 2 Valette Monophasic 20 Gestodene 0.075 Harmonet, Meliane Monophasic 30 Gestodene 0.075 Ciclomex, Evacin, Femodeen, Femoden, Femodene, Femovan, Ginera, Ginoden, Gynera, Gynovin, Minulet, Minulette, Moneva, Myvlar Triphasic 30/40/30 Gestodene 0.05/0.07/0.1 Milvane, Phaeva, Triadene, Tricilomex, Tri- Femoden, Trigynera, Tri-Gynera, Trigynovin, Triminulet, Triodeen, Trioden, Triodena, Triodene Monophasic 20 Levonorgestrel 0.1 Miranova Minisiston, Monostep Monophasic 30 Levonorgestrel 0.125 615 616 Table 1 (contd) Combination Trade names -

Association of Hormonal Contraception with Depression

Supplementary Online Content Skovlund CW, Mørch LS, Kessing LV, Lidegaard Ø. Association of hormonal contraception with depression. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online September 28, 2016. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2387 eFigure 1. Women and Person-years Fulfilling Various Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria eFigure 2. Use of Different Types of Hormonal Contraceptives According to Age in Denmark 2013 eFigure 3. Use of Antidepressants in Users of Different Types of Hormonal Contraceptives Among Parous Women 15-34 Years Old eTable 1. Included Groups of Hormonal Contraceptives and Corresponding Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Codes eTable 2. Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Codes of the Included Antidepressants eTable 3. Relative Risk of First Use of Antidepressants in Users of Different Types of Hormonal Contraceptives Compared With Users of Combined Oral Contraceptives With Levonorgestrel eTable 4. Relative Risk of First Use of Antidepressants Compared With Never-Users of Hormonal Contraceptives eTable 5. Relative Risk of First Use of Antidepressants in Starters of Different Types of Hormonal Contraceptives: Adolescents 15-19 Years of Age and Women 20-30 Years of Age eTable 6. Overview of Articles on Hormonal Contraception and Depression eDiscussion. Comparison With Prior Studies This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/27/2021 eFigure 1. Women and Person-years Fulfilling Various Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria 1,359,499 all women living in Denmark 15–34 years 2000–2013 identified 243,012 Immigrated after 1995 1,887 Cancer 1,686 VTE-event 16,350 IVF-treatment 4,701 Psychiatric diagnoses 4,203 Depression diagnoses 27,063 Antidepressant use 1,061,997 women inclued in the study 6,832,938 person-years observation time after censoring 3,791,343 person-years of exposed to hormonal contraception © 2016 American Medical Association. -

Precautions Interactions Pharmacokinetics Uses and Administration

2266 Sex Hormones and their Modulators sufficient to cause distress, has been described in a woman Preparations and is mainly excreted as peptide fragments in the faeces. given danazol for mastalgia. The hirsutism improved after About 20 to 30% of a dose is renally excreted. Degarelix is stopping the danazol.' ProprietaryPreparations (details are given in Volume B) injected to form a subcutaneous depot, and the I. Gately LE, Andes WA. Danazol and erythema multiforrne. Ann Intern Single-ingredient Preparations. Arg.: Ladoga!; Austral.: Azol; pharmacokinetics of the drug is strongly Influenced by the Med 1988; 109: 85. Danocrinet; Austria: Danokrin; Belg.: Danatrol; Braz.: Ladogal; concentration of the injected solution. After subcutaneous 2. Reynolds NJ, Sansom JE. Erythema multiforme during danazol therapy. Canad. : Cyclamen; China: Gong Fu Yi Kang (:g;ffl!jj>�); Cz. : injection of 240 mg at a concentration of 40 mg/mL, Clin Exp Dermato/ 1992; 17: 140. 3. Zawar V, Sankalecha C. Facial hirsutism following danazol therapy. Cutis Danoval; Fr.: Danatrol; Gr.: Danatrol; Hong Kong: Anargil; degarelix has a terminal half-life of about 43 to 53 days; after 2004; 74: 301-3. Azolt; Danocrine; Hung.: Danoval; India: Benzol; Danogen; maintenance doses of 80 mg as 20 mg/mL the half-life is Endozol; Gonablok; Gynadom; Gynazol; Gynodan; Ladoga!; about 28 days. Zendol; Indon.: Azol; Danocrine; Irl.: Danolt; Israel: Danol; Precautions Ital.: Danatrol; Jpn: Bonzol; Malaysia: Anargil; Azolt; Ladogal; Preparat ons Nazol; Mex. : Danalem; Ladogal; Novaprin; Neth.: Danatrol; NZ: i . Danazol should be used with caution in conditions that may ······························· ................................ Azol; D-Zolt; Philipp.: Ladoga!; Port. : Danatrol; Rus.: Danol ProprietaryPreparations (details are given in Volume B) be adversely affected by fluid retention, such as in (,!\aHon); Danoval (,!\aHoBaJJ); S.Afr. -

Of 31 Revised 08/2017

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION WARNING AND PRECAUTIONS These highlights do not include all the information needed • Vascular risks: Stop drospirenone and ethinyl estradiol to use DROSPIRENONE AND ETHINYL ESTRADIOL tablets if a thrombotic event occurs. Stop at least 4 weeks TABLETS safely and effectively. See full prescribing before and through 2 weeks after major surgery. Start no earlier than 4 weeks after delivery, in women who are not information for DROSPIRENONE AND ETHINYL breastfeeding (5.1). COCs containing DRSP may be ESTRADIOL TABLETS. associated with a higher risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) than COCs containing levonorgestrel or some other DROSPIRENONE and ETHINYL ESTRADIOL tablets, for progestins. Before initiating drospirenone and ethinyl oral use. estradiol tablets in a new COC user or a woman who is Initial U.S. Approval: 2001 switching from a contraceptive that does not contain DRSP, consider the risks and benefits of a DRSP-containing COC in light of her risk of a VTE (5.1). WARNI NG: CIGARETTE SMOKING AND SERIOUS CARDIOVASCULAR EVENTS • Hyperkalemia: DRSP has anti-mineralocorticoid activity. See full prescribing information for complete boxed Do not use in patients predisposed to hyperkalemia. Check warning. serum potassium concentration during the first treatment • Women over 35 years old who smoke should cycle in women on long-term treatment with medications that may increase serum potassium concentration. (5.2, 7.1, not use drospirenone and ethinyl estradiol tablets (4). 7.2) • • Liver disease: Discontinue drospirenone and ethinyl estradiol Cigarette smoking increases the risk of serious cardiovascular events from tablets if jaundice occurs. (5.4) combination oral contraceptive (COC) use. -

Novel Sugar Coating Composition for Application to Compressed Medicinal Tablets

Europaisches Patentamt (19) European Patent Office Office europeeneen des brevets £P 0 722 720 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.e: A61K 9/20 24.07.1996 Bulletin 1996/30 (21) Application number: 96300284.5 (22) Date of filing: 15.01.1996 (84) Designated Contracting States: (72) Inventor: Barcomb, Reginald Joseph AT BE CH DE DK ES FR GB GR IE IT LI LU NL PT Mooers Forks, New York 12959 (US) SE (74) Representative: Wileman, David Francis, Dr. et al (30) Priority: 17.01.1995 US 373667 c/o Wyeth Laboratories Huntercombe Lane South (71) Applicant: AMERICAN HOME PRODUCTS Taplow Maidenhead Berkshire SL6 OPH (GB) CORPORATION Madison, New Jersey 07940-0874 (US) (54) Novel sugar coating composition for application to compressed medicinal tablets (57) A sugar coating composition for application to dose of a hormonal steroid and a steroid release rate a compressed medicinal tablet comprising a sugar, a controlling amount of microcrystalline cellulose. < O CM Is- CM CM Is- O Q_ LU Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) EP 0 722 720 A1 Description The present invention relates to novel sugar coating compositions for application to compressed medicinal tablets, compressed tablets coated with the compositions and to methods of preparing the compositions and tablets. More 5 particularly the invention relates to the sustained release of steroids from the novel coatings. In the past three decades, substantial effort has gone into the identification of methods for controlling the rate of release of drug from pharmaceutical tablets. Excipients have been incorporated into tablet cores to control dissolution, and hence absorption, of drugs.