Human Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissues (GALT); Diversity, Structure, and Function

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mouth Esophagus Stomach Rectum and Anus Large Intestine Small

1 Liver The liver produces bile, which aids in digestion of fats through a dissolving process known as emulsification. In this process, bile secreted into the small intestine 4 combines with large drops of liquid fat to form Healthy tiny molecular-sized spheres. Within these spheres (micelles), pancreatic enzymes can break down fat (triglycerides) into free fatty acids. Pancreas Digestion The pancreas not only regulates blood glucose 2 levels through production of insulin, but it also manufactures enzymes necessary to break complex The digestive system consists of a long tube (alimen- 5 carbohydrates down into simple sugars (sucrases), tary canal) that varies in shape and purpose as it winds proteins into individual amino acids (proteases), and its way through the body from the mouth to the anus fats into free fatty acids (lipase). These enzymes are (see diagram). The size and shape of the digestive tract secreted into the small intestine. varies in each individual (e.g., age, size, gender, and disease state). The upper part of the GI tract includes the mouth, throat (pharynx), esophagus, and stomach. The lower Gallbladder part includes the small intestine, large intestine, The gallbladder stores bile produced in the liver appendix, and rectum. While not part of the alimentary 6 and releases it into the duodenum in varying canal, the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are all organs concentrations. that are vital to healthy digestion. 3 Small Intestine Mouth Within the small intestine, millions of tiny finger-like When food enters the mouth, chewing breaks it 4 protrusions called villi, which are covered in hair-like down and mixes it with saliva, thus beginning the first 5 protrusions called microvilli, aid in absorption of of many steps in the digestive process. -

Multiple Epithelia Are Required to Develop Teeth Deep Inside the Pharynx

Multiple epithelia are required to develop teeth deep inside the pharynx Veronika Oralováa,1, Joana Teixeira Rosaa,2, Daria Larionovaa, P. Eckhard Wittena, and Ann Huysseunea,3 aResearch Group Evolutionary Developmental Biology, Biology Department, Ghent University, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium Edited by Irma Thesleff, Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, and approved April 1, 2020 (received for review January 7, 2020) To explain the evolutionary origin of vertebrate teeth from closure of the gill slits (15). Consequently, previous studies have odontodes, it has been proposed that competent epithelium spread stressed the importance of gill slits for pharyngeal tooth formation into the oropharyngeal cavity via the mouth and other possible (12, 13). channels such as the gill slits [Huysseune et al., 2009, J. Anat. 214, Gill slits arise in areas where ectoderm meets endoderm. In 465–476]. Whether tooth formation deep inside the pharynx in ex- vertebrates, the endodermal epithelium of the developing pharynx tant vertebrates continues to require external epithelia has not produces a series of bilateral outpocketings, called pharyngeal been addressed so far. Using zebrafish we have previously demon- pouches, that eventually contact the skin ectoderm at corre- strated that cells derived from the periderm penetrate the oropha- sponding clefts (16). In primary aquatic osteichthyans, most ryngeal cavity via the mouth and via the endodermal pouches and pouch–cleft contacts eventually break through to create openings, connect to periderm-like cells that subsequently cover the entire or gill slits (17–19). In teleost fishes, such as the zebrafish, six endoderm-derived pharyngeal epithelium [Rosa et al., 2019, Sci. -

Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 3 Print Reference: Pages 335-342 Article 30 1994 Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix Frank Maas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Maas, Frank (1994) "Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 3 , Article 30. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol3/iss1/30 IMMUNE FUNCTIONS OF THE VERMIFORM APPENDIX FRANK MAAS, M.S. 320 7TH STREET GERVAIS, OR 97026 KEYWORDS Mucosal immunology, gut-associated lymphoid tissues. immunocompetence, appendix (human and rabbit), appendectomy, neoplasm, vestigial organs. ABSTRACT The vermiform appendix Is purported to be the classic example of a vestigial organ, yet for nearly a century it has been known to be a specialized organ highly infiltrated with lymphoid tissue. This lymphoid tissue may help protect against local gut infections. As the vertebrate taxonomic scale increases, the lymphoid tissue of the large bowel tends to be concentrated In a specific region of the gut: the cecal apex or vermiform appendix. -

Anatomy of Small Intestine Doctors Notes Notes/Extra Explanation Please View Our Editing File Before Studying This Lecture to Check for Any Changes

Color Code Important Anatomy of Small Intestine Doctors Notes Notes/Extra explanation Please view our Editing File before studying this lecture to check for any changes. Objectives: At the end of the lecture, students should: List the different parts of small intestine. Describe the anatomy of duodenum, jejunum & ileum regarding: the shape, length, site of beginning & termination, peritoneal covering, arterial supply & lymphatic drainage. Differentiate between each part of duodenum regarding the length, level & relations. Differentiate between the jejunum & ileum regarding the characteristic anatomical features of each of them. Abdomen What is Mesentery? It is a double layer attach the intestine to abdominal wall. If it has mesentery it is freely moveable. L= liver, S=Spleen, SI=Small Intestine, AC=Ascending Colon, TC=Transverse Colon Abdomen The small intestines consist of two parts: 1- fixed part (no mesentery) (retroperitoneal) : duodenum 2- free (movable) part (with mesentery) :jejunum & ileum Only on the boys’ slides RELATION BETWEEN EMBRYOLOGICAL ORIGIN & ARTERIAL SUPPLY مهم :Extra Arterial supply depends on the embryological origin : Foregut Coeliac trunk Midgut superior mesenteric Hindgut Inferior mesenteric Duodenum: • Origin: foregut & midgut • Arterial supply: 1. Coeliac trunk (artery of foregut) 2. Superior mesenteric: (artery of midgut) The duodenum has 2 arterial supply because of the double origin The junction of foregut and midgut is at the second part of the duodenum Jejunum & ileum: • Origin: midgut • Arterial -

Appendicitis

Appendicitis National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse The appendix is a small, tube-like structure abdomen. Anyone can get appendicitis, attached to the first part of the large intes- but it occurs most often between the ages tine, also called the colon. The appendix of 10 and 30. is located in the lower right portion of National Institute of the abdomen. It has no known function. Diabetes and Removal of the appendix appears to cause Causes Digestive The cause of appendicitis relates to block- and Kidney no change in digestive function. Diseases age of the inside of the appendix, known Appendicitis is an inflammation of the as the lumen. The blockage leads to NATIONAL INSTITUTES appendix. Once it starts, there is no effec- increased pressure, impaired blood flow, OF HEALTH tive medical therapy, so appendicitis is and inflammation. If the blockage is not considered a medical emergency. When treated, gangrene and rupture (breaking treated promptly, most patients recover or tearing) of the appendix can result. without difficulty. If treatment is delayed, the appendix can burst, causing infection Most commonly, feces blocks the inside and even death. Appendicitis is the most of the appendix. Also, bacterial or viral common acute surgical emergency of the infections in the digestive tract can lead to Inflamed appendix Small intestine Appendix Large intestine U.S. Department The appendix is a small, tube-like structure attached to the first part of the large intestine, also called the colon. The of Health and appendix is located in the lower right portion of the abdomen, near where the small intestine attaches to the large Human Services intestine. -

Short Bowel Syndrome with Intestinal Failure Were Randomized to Teduglutide (0.05 Mg/Kg/Day) Or Placebo for 24 Weeks

Short Bowel (Gut) Syndrome LaTasha Henry February 25th, 2016 Learning Objectives • Define SBS • Normal function of small bowel • Clinical Manifestation and Diagnosis • Management • Updates Basic Definition • A malabsorption disorder caused by the surgical removal of the small intestine, or rarely it is due to the complete dysfunction of a large segment of bowel. • Most cases are acquired, although some children are born with a congenital short bowel. Intestinal Failure • SBS is the most common cause of intestinal failure, the state in which an individual’s GI function is inadequate to maintain his/her nutrient and hydration status w/o intravenous or enteral supplementation. • In addition to SBS, diseases or congenital defects that cause severe malabsorption, bowel obstruction, and dysmotility (eg, pseudo- obstruction) are causes of intestinal failure. Causes of SBS • surgical resection for Crohn’s disease • Malignancy • Radiation • vascular insufficiency • necrotizing enterocolitis (pediatric) • congenital intestinal anomalies such as atresias or gastroschisis (pediatric) Length as a Determinant of Intestinal Function • The length of the small intestine is an important determinant of intestinal function • Infant normal length is approximately 125 cm at the start of the third trimester of gestation and 250 cm at term • <75 cm are at risk for SBS • Adult normal length is approximately 400 cm • Adults with residual small intestine of less than 180 cm are at risk for developing SBS; those with less than 60 cm of small intestine (but with a -

Anatomy of the Small Intestine

Anatomy of the small intestine Make sure you check this Correction File before going through the content Small intestine Fixed Free (Retro peritoneal part) (Movable part) (No mesentery) (With mesentery) Duodenum Jejunum & ileum Duodenum Shape C-shaped loop Duodenal parts Length 10 inches Length Level Beginning At pyloro-duodenal Part junction FIRST PART 2 INCHES L1 (Superior) (Transpyloric Termination At duodeno-jejunal flexure Plane) SECOND PART 3 INCHES DESCENDS Peritoneal Retroperitoneal (Descending FROM L1 TO covering L3 Divisions 4 parts THIRD PART 4 INCHES L3 (SUBCOTAL (Horizontal) PLANE) Embryologic Foregut & midgut al origin FOURTH PART 1 INCHES ASCENDS Lymphatic Celiac & superior (Ascending) FROM L3 TO drainage mesenteric L2 Arterial Celiac & superior supply mesenteric Venous Superior mesenteric& Drainage Portal veins Duodenal relations part Anterior Posterior Medial Lateral First part Liver Bile duct - - Gastroduodenal artery Portal vein Second Part Liver Transverse Right kidney Pancreas Right colic flexure Colon Small intestine Third Part Small intestine Right psoas major - - Superior Inferior vena cava mesenteric vessels Abdominal aorta Inferior mesenteric vessels Fourth Part Small intestine Left psoas major - - Openings in second part of the duodenum Opening of accessory Common opening of bile duct pancreatic duct (one inch & main pancreatic duct: higher): on summit of major duodenal on summit of minor duodenal papilla. papilla. Jejunum & ileum Shape Coiled tube Length 6 meters (20 feet) Beginning At duodeno-jejunal flexur -

Reflux Esophagitis

Reflux Esophagitis KEY FACTS TERMINOLOGY • Caustic esophagitis • Inflammation of esophageal mucosa due to PATHOLOGY gastroesophageal (GE) reflux • Lower esophageal sphincter: Decreased tone leads to IMAGING increased reflux • Irregular ulcerated mucosa of distal esophagus • Hydrochloric acid and pepsin: Synergistic effect • Foreshortening of esophagus: Due to muscle spasm CLINICAL ISSUES • Inflammatory esophagogastric polyps: Smooth, ovoid • 15-20% of Americans commonly have heartburn due to elevations reflux; ~ 30% fail to respond to standard-dose medical • Hiatal hernia in > 95% of patients with stricture therapy ○ Probably is result, not cause, of reflux ○ Prevalence of GE reflux disease has increased sharply • Peptic stricture (1- to 4-cm length): Concentric, smooth, with obesity epidemic tapered narrowing of distal esophagus • Symptoms: Heartburn, regurgitation, angina-like pain TOP DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES ○ Dysphagia, odynophagia • Scleroderma • Confirmatory testing: Manometric/ambulatory pH- monitoring techniques • Drug-induced esophagitis ○ Endoscopy, biopsy • Infectious esophagitis Imaging in Gastrointestinal Disorders: Diagnoses • Eosinophilic esophagitis (Left) Graphic shows a small type 1 (sliding) hiatal hernia ſt linked with foreshortening of the esophagus, ulceration of the mucosa, and a tapered stricture of distal esophagus. (Right) Spot film from an esophagram shows a small hiatal hernia with gastric folds ſt extending above the diaphragm. The esophagus appears shortened, presumably due to spasm of its longitudinal muscles. A stricture is present at the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, and persistent collections of barium indicate mucosal ulceration. (Left) Prone film from an esophagram shows a tight stricture ſt just above the GE junction with upstream dilation of the esophagus. The herniated stomach is pulled taut as a result of the foreshortening of the esophagus, a common and important sign of reflux esophagitis. -

Appendix B: Muscles of the Speech Production Mechanism

Appendix B: Muscles of the Speech Production Mechanism I. MUSCLES OF RESPIRATION A. MUSCLES OF INHALATION (muscles that enlarge the thoracic cavity) 1. Diaphragm Attachments: The diaphragm originates in a number of places: the lower tip of the sternum; the first 3 or 4 lumbar vertebrae and the lower borders and inner surfaces of the cartilages of ribs 7 - 12. All fibers insert into a central tendon (aponeurosis of the diaphragm). Function: Contraction of the diaphragm draws the central tendon down and forward, which enlarges the thoracic cavity vertically. It can also elevate to some extent the lower ribs. The diaphragm separates the thoracic and the abdominal cavities. 2. External Intercostals Attachments: The external intercostals run from the lip on the lower border of each rib inferiorly and medially to the upper border of the rib immediately below. Function: These muscles may have several functions. They serve to strengthen the thoracic wall so that it doesn't bulge between the ribs. They provide a checking action to counteract relaxation pressure. Because of the direction of attachment of their fibers, the external intercostals can raise the thoracic cage for inhalation. 3. Pectoralis Major Attachments: This muscle attaches on the anterior surface of the medial half of the clavicle, the sternum and costal cartilages 1-6 or 7. All fibers come together and insert at the greater tubercle of the humerus. Function: Pectoralis major is primarily an abductor of the arm. It can, however, serve as a supplemental (or compensatory) muscle of inhalation, raising the rib cage and sternum. (In other words, breathing by raising and lowering the arms!) It is mentioned here chiefly because it is encountered in the dissection. -

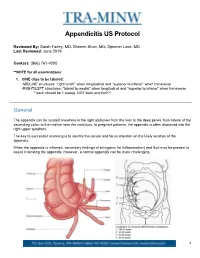

Appendicitis US Protocol

Appendicitis US Protocol Reviewed By: Sarah Farley, MD; Shireen Khan, MD; Spencer Lake, MD Last Reviewed: June 2019 Contact: (866) 761-4200 **NOTE for all examinations: 1. CINE clips to be labeled: -MIDLINE structures: “right to left” when longitudinal and “superior to inferior” when transverse -RIGHT/LEFT structures: “lateral to medial” when longitudinal and “superior to inferior” when transverse **each should be 1 sweep, NOT back and forth** General The appendix can be located anywhere in the right abdomen from the liver to the deep pelvis, from lateral of the ascending colon to the midline near the umbilicus. In pregnant patients, the appendix is often displaced into the right upper quadrant. The key to successful scanning is to identify the cecum and focus attention on the likely location of the appendix. When the appendix is inflamed, secondary findings of echogenic fat (inflammation) and fluid may be present to assist in locating the appendix. However, a normal appendix can be more challenging. 1 Strategies for finding the appendix include: 1. Review prior CT abdomen/pelvis or appendix US to see where appendix has been previously. 2. Scan in area of greatest pain (indicated by focal tenderness by 1 finger, not general pain). Label as such. 3. Localize cecum. 4. Localize ileocecal valve, if possible. Equipment: 1. Linear high frequency transducer is required, as this will best demonstrate anatomy of appendix. 2. In larger or obese patients, a curved lower frequency transducer may be used to obtain an overview and localize the cecum first. THEN, switch to the linear probe. a. When you locate the appendix, turn ON harmonics to better visualize the walls and appendiceal lumen together. -

What Is an Enteral Feeding Tube?

Your Feeding Tubes Feeding Your What Is an Enteral Feeding Tube? Enteral refers to within the digestive system or intestine. Enteral feeding tubes allow liquid food to enter your stomach or intestine through a tube. The soft, flexible tube enters a surgically created opening in the abdominal wall called an ostomy. An enterostomy tube in the stomach is called a gastrostomy. A tube in the small intestine is called a jejunostomy. The site on the abdomen where the tube is inserted is called a stoma. The location of the stoma depends on your specific operation and the shape of your abdomen. Most stomas: f Lie flat against your body f Are round in shape f Are red and moist (similar to the inside of your mouth) f Have no feeling Gastrostomy feeding tube Stoma tract Surgical Patient Education 112830_BODY.indd 1 8/21/15 9:25 AM 3 Who Needs an Enteral Feeding Tube? Cancer, trauma, nervous system and digestive system disorders, and congenital birth defects can cause difficulty in feeding. Some people also have difficulty swallowing, which increases the chance that they will breathe in food (aspirate). People who have difficulties feeding can benefit from a feeding tube. Your doctor will explain to you the specific reasons why you or your family member need a feeding tube. For some, a feeding tube is a new way of life, but for others, the tube is temporary and used until the problem can be treated or repaired. Low-profile feeding tube American College of Surgeons • Division of Education 112830_BODY.indd 2 8/21/15 9:25 AM 2 Your Feeding Tubes Feeding Your Understanding Your Digestive System When food enters your oral cavity (mouth), the lips and tongue move it toward the back of the throat. -

Digestive System A&P DHO 7.11 Digestive System

Digestive System A&P DHO 7.11 Digestive System AKA gastrointestinal system or GI system Function=responsible for the physical & chemical breakdown of food (digestion) so it can be taken into bloodstream & be used by body cells & tissues (absorption) Structures=divided into alimentary canal & accessory organs Alimentary Canal Long muscular tube Includes: 1. Mouth 2. Pharynx 3. Esophagus 4. Stomach 5. Small intestine 6. Large intestine 1. Mouth Mouth=buccal cavity Where food enters body, is tasted, broken down physically by teeth, lubricated & partially digested by saliva, & swallowed Teeth=structures that physically break down food by chewing & grinding in a process called mastication 1. Mouth Tongue=muscular organ, contains taste buds which allow for sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami (meaty or savory) sensations Tongue also aids in chewing & swallowing 1. Mouth Hard palate=bony structure, forms roof of mouth, separates mouth from nasal cavities Soft palate=behind hard palate; separates mouth from nasopharynx Uvula=cone-shaped muscular structure, hangs from middle of soft palate; prevents food from entering nasopharynx during swallowing 1. Mouth Salivary glands=3 pairs (parotid, sublingual, & submandibular); produce saliva Saliva=liquid that lubricates mouth during speech & chewing, moistens food so it can be swallowed Salivary amylase=saliva enzyme (substance that speeds up a chemical reaction) starts the chemical breakdown of carbohydrates (starches) into sugar 2. Pharynx Bolus=chewed food mixed with saliva Pharynx=throat; tube that carries air & food Air goes to trachea; food goes to esophagus When bolus is swallowed, epiglottis covers larynx which stops bolus from entering respiratory tract and makes it go into esophagus 3.