Immune Functions of the Vermiform Appendix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utility of the Digital Rectal Examination in the Emergency Department: a Review

The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 43, No. 6, pp. 1196–1204, 2012 Published by Elsevier Inc. Printed in the USA 0736-4679/$ - see front matter http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.06.015 Clinical Reviews UTILITY OF THE DIGITAL RECTAL EXAMINATION IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT: A REVIEW Chad Kessler, MD, MHPE*† and Stephen J. Bauer, MD† *Department of Emergency Medicine, Jesse Brown VA Medical Center and †University of Illinois-Chicago College of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois Reprint Address: Chad Kessler, MD, MHPE, Department of Emergency Medicine, Jesse Brown Veterans Hospital, 820 S Damen Ave., M/C 111, Chicago, IL 60612 , Abstract—Background: The digital rectal examination abdominal pain and acute appendicitis. Stool obtained by (DRE) has been reflexively performed to evaluate common DRE doesn’t seem to increase the false-positive rate of chief complaints in the Emergency Department without FOBTs, and the DRE correlated moderately well with anal knowing its true utility in diagnosis. Objective: Medical lit- manometric measurements in determining anal sphincter erature databases were searched for the most relevant arti- tone. Published by Elsevier Inc. cles pertaining to: the utility of the DRE in evaluating abdominal pain and acute appendicitis, the false-positive , Keywords—digital rectal; utility; review; Emergency rate of fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) from stool obtained Department; evidence-based medicine by DRE or spontaneous passage, and the correlation be- tween DRE and anal manometry in determining anal tone. Discussion: Sixteen articles met our inclusion criteria; there INTRODUCTION were two for abdominal pain, five for appendicitis, six for anal tone, and three for fecal occult blood. -

The Differences Between ICD-9 and ICD-10

Preparing for the ICD-10 Code Set: Fact Sheet 2 October 1, 2015 Compliance Date Get the Facts to be Compliant Alert: The new ICD-10 compliance date is October 1, 2015. The Differences Between ICD-9 and ICD-10 This is the second fact sheet in a series and is focused on the differences between the ICD-9 and ICD-10 code sets. Collectively, the fact sheets will provide information, guidance, and checklists to assist you with understanding what you need to do to implement the ICD-10 code set. The ICD-10 code sets are not a simple update of the ICD-9 code set. The ICD-10 code sets have fundamental changes in structure and concepts that make them very different from ICD-9. Because of these differences, it is important to develop a preliminary understanding of the changes from ICD-9 to ICD-10. This basic understanding of the differences will then identify more detailed training that will be needed to appropriately use the ICD-10 code sets. In addition, seeing the differences between the code sets will raise awareness of the complexities of converting to the ICD-10 codes. Overall Comparisons of ICD-9 to ICD-10 Issues today with the ICD-9 diagnosis and procedure code sets are addressed in ICD-10. One concern today with ICD-9 is the lack of specificity of the information conveyed in the codes. For example, if a patient is seen for treatment of a burn on the right arm, the ICD-9 diagnosis code does not distinguish that the burn is on the right arm. -

Mouth Esophagus Stomach Rectum and Anus Large Intestine Small

1 Liver The liver produces bile, which aids in digestion of fats through a dissolving process known as emulsification. In this process, bile secreted into the small intestine 4 combines with large drops of liquid fat to form Healthy tiny molecular-sized spheres. Within these spheres (micelles), pancreatic enzymes can break down fat (triglycerides) into free fatty acids. Pancreas Digestion The pancreas not only regulates blood glucose 2 levels through production of insulin, but it also manufactures enzymes necessary to break complex The digestive system consists of a long tube (alimen- 5 carbohydrates down into simple sugars (sucrases), tary canal) that varies in shape and purpose as it winds proteins into individual amino acids (proteases), and its way through the body from the mouth to the anus fats into free fatty acids (lipase). These enzymes are (see diagram). The size and shape of the digestive tract secreted into the small intestine. varies in each individual (e.g., age, size, gender, and disease state). The upper part of the GI tract includes the mouth, throat (pharynx), esophagus, and stomach. The lower Gallbladder part includes the small intestine, large intestine, The gallbladder stores bile produced in the liver appendix, and rectum. While not part of the alimentary 6 and releases it into the duodenum in varying canal, the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are all organs concentrations. that are vital to healthy digestion. 3 Small Intestine Mouth Within the small intestine, millions of tiny finger-like When food enters the mouth, chewing breaks it 4 protrusions called villi, which are covered in hair-like down and mixes it with saliva, thus beginning the first 5 protrusions called microvilli, aid in absorption of of many steps in the digestive process. -

Appendectomy: Simple Appendicitis

Appendectomy: Simple Appendicitis Your child has had an appendectomy (ap pen DECK toe mee). This is the surgical removal of the appendix. The appendix is a small, narrow sac at the beginning of the large intestine (Picture 1). The appendix has no known function. What to Expect After Surgery . Your child will awaken in the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) near the surgery area. He or she may be in the PACU for 1 to 2 hours. After your child wakes up in the PACU, he or she will return to a hospital room or be Esophagus transferred to the Surgery Unit. Discharge will be directly from the Surgery Unit. Liver Stomach . Your child will have 3 to 4 small incision Large sites (see Helping Hand HH-I-283, Intestines Laparoscopic Surgery (colon) ). Small . Your child will receive fluids and pain intestines medicine through an intravenous line (IV). Rectum When your child can take liquids by mouth, pain medicine will also be given by mouth. Appendix . Your child will need to cough and deep-breathe often to help keep the lungs clear. He or she may use a plastic device called an incentive Picture 1 The appendix inside the body. spirometer to help with this. Your child will need to get up and walk soon after surgery. Walking will help "wake up" the bowels; it will also help with breathing and blood flow. Your child will be able to go home on the same day of the surgery if he or she is: o able to drink clear liquids like water, clear soft drinks, broth, and fruit punch o taking pain medicine by mouth and his or her pain is controlled, and o able to walk. -

Multiple Epithelia Are Required to Develop Teeth Deep Inside the Pharynx

Multiple epithelia are required to develop teeth deep inside the pharynx Veronika Oralováa,1, Joana Teixeira Rosaa,2, Daria Larionovaa, P. Eckhard Wittena, and Ann Huysseunea,3 aResearch Group Evolutionary Developmental Biology, Biology Department, Ghent University, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium Edited by Irma Thesleff, Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, and approved April 1, 2020 (received for review January 7, 2020) To explain the evolutionary origin of vertebrate teeth from closure of the gill slits (15). Consequently, previous studies have odontodes, it has been proposed that competent epithelium spread stressed the importance of gill slits for pharyngeal tooth formation into the oropharyngeal cavity via the mouth and other possible (12, 13). channels such as the gill slits [Huysseune et al., 2009, J. Anat. 214, Gill slits arise in areas where ectoderm meets endoderm. In 465–476]. Whether tooth formation deep inside the pharynx in ex- vertebrates, the endodermal epithelium of the developing pharynx tant vertebrates continues to require external epithelia has not produces a series of bilateral outpocketings, called pharyngeal been addressed so far. Using zebrafish we have previously demon- pouches, that eventually contact the skin ectoderm at corre- strated that cells derived from the periderm penetrate the oropha- sponding clefts (16). In primary aquatic osteichthyans, most ryngeal cavity via the mouth and via the endodermal pouches and pouch–cleft contacts eventually break through to create openings, connect to periderm-like cells that subsequently cover the entire or gill slits (17–19). In teleost fishes, such as the zebrafish, six endoderm-derived pharyngeal epithelium [Rosa et al., 2019, Sci. -

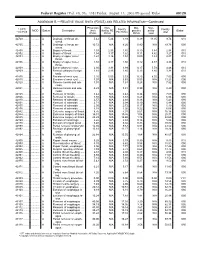

RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) and RELATED INFORMATION—Continued

Federal Register / Vol. 68, No. 158 / Friday, August 15, 2003 / Proposed Rules 49129 ADDENDUM B.—RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) AND RELATED INFORMATION—Continued Physician Non- Mal- Non- 1 CPT/ Facility Facility 2 MOD Status Description work facility PE practice acility Global HCPCS RVUs RVUs PE RVUs RVUs total total 42720 ....... ........... A Drainage of throat ab- 5.42 5.24 3.93 0.39 11.05 9.74 010 scess. 42725 ....... ........... A Drainage of throat ab- 10.72 N/A 8.26 0.80 N/A 19.78 090 scess. 42800 ....... ........... A Biopsy of throat ................ 1.39 2.35 1.45 0.10 3.84 2.94 010 42802 ....... ........... A Biopsy of throat ................ 1.54 3.17 1.62 0.11 4.82 3.27 010 42804 ....... ........... A Biopsy of upper nose/ 1.24 3.16 1.54 0.09 4.49 2.87 010 throat. 42806 ....... ........... A Biopsy of upper nose/ 1.58 3.17 1.66 0.12 4.87 3.36 010 throat. 42808 ....... ........... A Excise pharynx lesion ...... 2.30 3.31 1.99 0.17 5.78 4.46 010 42809 ....... ........... A Remove pharynx foreign 1.81 2.46 1.40 0.13 4.40 3.34 010 body. 42810 ....... ........... A Excision of neck cyst ........ 3.25 5.05 3.53 0.25 8.55 7.03 090 42815 ....... ........... A Excision of neck cyst ........ 7.07 N/A 5.63 0.53 N/A 13.23 090 42820 ....... ........... A Remove tonsils and ade- 3.91 N/A 3.63 0.28 N/A 7.82 090 noids. -

Incidental Drainage of a Periappendicular Abscess During Colonoscopy

UCTN – Unusual cases and technical notes E175 Incidental drainage of a periappendicular abscess during colonoscopy A 50-year-old man was referred to the of oral metronidazole and ciprofloxacin. A P. Figueiredo, V. Fernandes, J. Freitas outpatient colonoscopy clinic after a posi- computed tomography (CT) scan 1 week Department of Gastroenterology, tive fecal occult blood test during screen- after the procedure revealed no abnormal Hospital Garcia de Orta, Almada, Portugal ing for colorectal cancer. Colonoscopy, findings and the patient remained asymp- which was performed with the patient tomatic. sedated, revealed a 12-mm tumor covered Acute appendicitis is the most frequent References by normal, smooth mucosa at the site of acute abdominal emergency seen in de- 1 Oliak D, Yamini D, Udani VM et al. Can per- forated appendicitis be diagnosed preopera- the appendicular orifice. A biopsy was veloped countries. Its most common com- tively based on admission factors? J Gastro- taken, but this led to an immediate puru- plication is perforation and this may be intest Surg 2000; 4: 470–474 lent discharge occurring from the lesion followed by abscess formation [1]. Colo- 2 Ohtaka M, Asakawa A, Kashiwagi A et al. (●" Video 1). Therefore, a diagnosis of a noscopic diagnosis and treatment of a Pericecal appendiceal abscess with drainage periappendicular abscess was incidentally periappendicular abscess is rare [2]. In during colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 1999; 49: 107–109 established. this case a periappendicular abscess was 3 Antevil J, Brown C. Percutaneous drainage After the patient had recovered from the incidentally discovered and drained dur- and interval appendectomy. In: Scott-Turner sedation, he was specifically questioned ing a colonoscopy. -

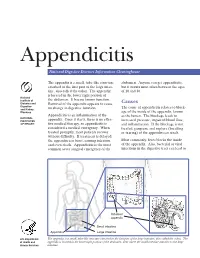

Appendicitis

Appendicitis National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse The appendix is a small, tube-like structure abdomen. Anyone can get appendicitis, attached to the first part of the large intes- but it occurs most often between the ages tine, also called the colon. The appendix of 10 and 30. is located in the lower right portion of National Institute of the abdomen. It has no known function. Diabetes and Removal of the appendix appears to cause Causes Digestive The cause of appendicitis relates to block- and Kidney no change in digestive function. Diseases age of the inside of the appendix, known Appendicitis is an inflammation of the as the lumen. The blockage leads to NATIONAL INSTITUTES appendix. Once it starts, there is no effec- increased pressure, impaired blood flow, OF HEALTH tive medical therapy, so appendicitis is and inflammation. If the blockage is not considered a medical emergency. When treated, gangrene and rupture (breaking treated promptly, most patients recover or tearing) of the appendix can result. without difficulty. If treatment is delayed, the appendix can burst, causing infection Most commonly, feces blocks the inside and even death. Appendicitis is the most of the appendix. Also, bacterial or viral common acute surgical emergency of the infections in the digestive tract can lead to Inflamed appendix Small intestine Appendix Large intestine U.S. Department The appendix is a small, tube-like structure attached to the first part of the large intestine, also called the colon. The of Health and appendix is located in the lower right portion of the abdomen, near where the small intestine attaches to the large Human Services intestine. -

Reflux Esophagitis

Reflux Esophagitis KEY FACTS TERMINOLOGY • Caustic esophagitis • Inflammation of esophageal mucosa due to PATHOLOGY gastroesophageal (GE) reflux • Lower esophageal sphincter: Decreased tone leads to IMAGING increased reflux • Irregular ulcerated mucosa of distal esophagus • Hydrochloric acid and pepsin: Synergistic effect • Foreshortening of esophagus: Due to muscle spasm CLINICAL ISSUES • Inflammatory esophagogastric polyps: Smooth, ovoid • 15-20% of Americans commonly have heartburn due to elevations reflux; ~ 30% fail to respond to standard-dose medical • Hiatal hernia in > 95% of patients with stricture therapy ○ Probably is result, not cause, of reflux ○ Prevalence of GE reflux disease has increased sharply • Peptic stricture (1- to 4-cm length): Concentric, smooth, with obesity epidemic tapered narrowing of distal esophagus • Symptoms: Heartburn, regurgitation, angina-like pain TOP DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES ○ Dysphagia, odynophagia • Scleroderma • Confirmatory testing: Manometric/ambulatory pH- monitoring techniques • Drug-induced esophagitis ○ Endoscopy, biopsy • Infectious esophagitis Imaging in Gastrointestinal Disorders: Diagnoses • Eosinophilic esophagitis (Left) Graphic shows a small type 1 (sliding) hiatal hernia ſt linked with foreshortening of the esophagus, ulceration of the mucosa, and a tapered stricture of distal esophagus. (Right) Spot film from an esophagram shows a small hiatal hernia with gastric folds ſt extending above the diaphragm. The esophagus appears shortened, presumably due to spasm of its longitudinal muscles. A stricture is present at the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, and persistent collections of barium indicate mucosal ulceration. (Left) Prone film from an esophagram shows a tight stricture ſt just above the GE junction with upstream dilation of the esophagus. The herniated stomach is pulled taut as a result of the foreshortening of the esophagus, a common and important sign of reflux esophagitis. -

Appendix B: Muscles of the Speech Production Mechanism

Appendix B: Muscles of the Speech Production Mechanism I. MUSCLES OF RESPIRATION A. MUSCLES OF INHALATION (muscles that enlarge the thoracic cavity) 1. Diaphragm Attachments: The diaphragm originates in a number of places: the lower tip of the sternum; the first 3 or 4 lumbar vertebrae and the lower borders and inner surfaces of the cartilages of ribs 7 - 12. All fibers insert into a central tendon (aponeurosis of the diaphragm). Function: Contraction of the diaphragm draws the central tendon down and forward, which enlarges the thoracic cavity vertically. It can also elevate to some extent the lower ribs. The diaphragm separates the thoracic and the abdominal cavities. 2. External Intercostals Attachments: The external intercostals run from the lip on the lower border of each rib inferiorly and medially to the upper border of the rib immediately below. Function: These muscles may have several functions. They serve to strengthen the thoracic wall so that it doesn't bulge between the ribs. They provide a checking action to counteract relaxation pressure. Because of the direction of attachment of their fibers, the external intercostals can raise the thoracic cage for inhalation. 3. Pectoralis Major Attachments: This muscle attaches on the anterior surface of the medial half of the clavicle, the sternum and costal cartilages 1-6 or 7. All fibers come together and insert at the greater tubercle of the humerus. Function: Pectoralis major is primarily an abductor of the arm. It can, however, serve as a supplemental (or compensatory) muscle of inhalation, raising the rib cage and sternum. (In other words, breathing by raising and lowering the arms!) It is mentioned here chiefly because it is encountered in the dissection. -

Hospital Confinement Sickness Indemnity Limited Benefit Policy Surgical Benefit

HOSPITAL CONFINEMENT SICKNESS INDEMNITY LIMITED BENEFIT POLICY SURGICAL BENEFIT AFLAC will pay benefits according to the Schedule of Operations when a covered person has a surgical operation performed for a covered sickness in a hospital or ambulatory surgical center. Only one benefit is payable per 24-hour period for surgery even though more than one surgical procedure may be performed. We will pay the highest eligible benefit. Benefits are not payable for cosmetic or elective surgery that is not due to sickness. Surgical Benefits are not payable for surgery performed in a doctor's or dentist's office, clinic, or other such location. Surgery performed but not listed in the Schedule of Operations will be paid according to the amount shown for the surgery most similar in severity and gravity. No lifetime maximum. SCHEDULE OF OPERATIONS BONE DIGESTIVE (cont.) Bone marrow biopsy Gastroscopy ................................... 100 or aspiration ............................. $100 Sigmoidoscopy ............................... 100 Arthroscopy.................................... 150 Appendectomy................................ 200 Removal of knee cartilage............. 150 Colostomy....................................... 300 Total knee replacement................. 500 ERCP .............................................. 300 Total hip replacement.................... 750 Vagotomy........................................ 300 Partial colectomy ............................ 400 BRAIN Colectomy....................................... 600 Burr holes not -

Benefit of Rectal Examination in Children with Acute Abdomen

Benefit of Rectal Examination in Children with Acute Abdomen Wasun Nuntasunti MD*, Mongkol Laohapensang MD** * Department of Surgery, Sisaket Hospital, Sisaket, Thailand ** Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand Background: Acute abdomen is a condition that often mandates urgent treatment. PR or DRE (per rectal examination or digital rectal examination) is one of the fundamental physical examinations that doctors use to differentiate causes of acute abdominal pain. However, it is not a pleasant examination to undergo. Sometimes doctors ignore this examination. The benefit of per rectal examination has rarely been studied in children. Objective: This study was designed to demonstrate the benefit of rectal examination for contribution to the diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in children and reduction of unnecessary operation. Material and Method: A prospective cross sectional study of children ages 3 to 15 years old who presented with acute abdominal pain from January 2012 to December 2013 was conducted. The clinical parameters including DRE results were correlated to the diagnosis. The diagnoses prior to and after DRE were compared. The accuracy of DRE was analyzed by pair response analysis of pre and post-DRE results using McNemar‘s Chi-square test. Results: A total of 116 children with acute abdominal pain were enrolled in the study. The final diagnoses were appendicitis accounting for 27%, constipation 28%, non-surgical gastrointestinal diseases such as gastritis, diarrhea and food poisoning 9%, diseases of the female reproductive system 7% and others 29%. In comparing the diagnoses prior to and after digital rectal examination, it was demonstrated that rectal examination significantly helped differentiate diagnosis in 38.8% of patients, whereas 19% of the patients gained no benefit.DRE corrected the diagnosis in 45 cases which was significantly higher than misguiding the diagnosis in 3 cases.