Map Matters 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTRUDERS ARRIVE 50,000 Years Ago 1616 1770

© Lonely Planet 33 History Dr Michael Cathcart INTRUDERS ARRIVE By sunrise the storm had passed. Zachary Hicks was keeping sleepy watch on the British ship Endeavour when suddenly he was wide awake. He sum- Dr Michael Cathcart moned his captain, James Cook, who climbed into the brisk morning air wrote the History to a miraculous sight. Ahead of them lay an uncharted country of wooded chapter. Michael teaches hills and gentle valleys. It was 19 April 1770. In the coming days Cook history at the Australian began to draw the first European map of Australia’s eastern coast. He was Centre, the University of mapping the end of Aboriginal supremacy. Melbourne. He is well Two weeks later Cook led a party of men onto a narrow beach. As known as a broadcaster they waded ashore, two Aboriginal men stepped onto the sand, and chal- on ABC Radio National lenged the intruders with spears. Cook drove the men off with musket and presented history fire. For the rest of that week, the Aborigines and the intruders watched programs on ABC TV. For each other warily. more information about Cook’s ship Endeavour was a floating annexe of London’s leading sci- Michael, see p1086. entific organisation, the Royal Society. The ship’s gentlemen passengers included technical artists, scientists, an astronomer and a wealthy bota- nist named Joseph Banks. As Banks and his colleagues strode about the Aborigines’ territory, they were delighted by the mass of new plants they collected. (The showy banksia flowers, which look like red, white or golden bottlebrushes, are named after Banks.) The local Aborigines called the place Kurnell, but Cook gave it a foreign name: he called it ‘ Botany Bay’. -

The Great Barrier Reef History, Science, Heritage

The Great Barrier Reef History, Science, Heritage One of the world’s natural wonders, the Great Barrier Reef stretches more than 2000 kilo- metres in a maze of coral reefs and islands along Australia’s north-eastern coastline. This book unfolds the fascinating story behind its mystique, providing for the first time a comprehensive cultural and ecological history of European impact, from early voyages of discovery to the most recent developments in Reef science and management. Incisive and a delight to read in its thorough account of the scientific, social and environmental consequences of European impact on the world’s greatest coral reef system and Australia’s greatest natural feature, this extraordinary book is sure to become a classic. After graduating from the University of Sydney and completing a PhD at the University of Illinois, James Bowen pursued an academic career in the United States, Canada and Australia, publishing extensively in the history of ideas and environmental thought. As visiting Professorial Fellow at the Australian National University from 1984 to 1989, he became absorbed in the complex history of the Reef, exploring this over the next decade through intensive archival, field and underwater research in collaboration with Margarita Bowen, ecologist and distinguished historian of science. The outcome of those stimulating years is this absorbing saga. To our grandchildren, with hope for the future in the hands of their generation The Great Barrier Reef History, Science, Heritage JAMES BOWEN AND MARGARITA BOWEN Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , United Kingdom Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521824309 © James Bowen & Margarita Bowen 2002 This book is in copyright. -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

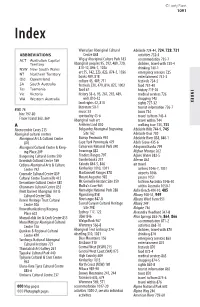

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Australasian Hydrographic Society

ARTICLE Australasian Hydrographic Society Early Hydrography Recognised Willem Janszoon Monument Unveiled in Canberra The last project commemorating the 400th anniversary of Australia first being charted took place recently in the leafy suburb of Griffith, within the Australian Capital Territory. On Saturday 20th October 2007, a three-in-one –launch was held: with the inauguration of the Willem Janszoon Commemorative Park, the issue of the Explorer’s Guide for a series of local walks and the unveiling of a Willem Janszoon Monument. The launch was organised by Australia On The Map (AOTM). Griffith and the surrounding suburbs, a predominantly diplomatic district, have the distinction of having nearly all the streets named after hydrographers, explorers or their ships. From Bass to Bougainville, from Van Diemen to Vancouver, from Cook to Carstensz, the list of avenues and boulevards include names such as Torres, Flinders, Moresby, La Perouse, Dalrymple, Hartog and, in all, totals some 150 streets and byways. Amongst such esteemed company, the dedication of a major park and monument in Janszoon’s name bares testament to his unique achievement in being the first European to chart the Australian coast, a feat he accomplished when he surveyed over 300 kilometres of Cape York in 1606. Similar to the long-awaited unveiling of the Willem de Vlamingh Monument in Perth, Western Australia, four days earlier, it has taken a long time to raise money, design and build the sculptured monument and, of course, obtain necessary sanctions and approvals. Both projects were meant to have been completed in 2006, but the end results were worth the wait. -

Point Hicks (Cape Everard) James Cook's Australian Landfall

SEPTEMBER 2014 Newsletter of the Australian National Placenames Survey an initiative of the Australian Academy of Humanities, supported by the Geographical Names Board of NSW Point Hicks (Cape Everard) James Cook's Australian landfall Early in the morning of 19 April 1770 Lieutenant Cook 12 miles from the nearest land. Map 1 (page 6, below) and the crew of Endeavour had their first glimpses of the shows the coast as laid down by Cook, the modern Australian continent on the far eastern coast of Victoria. coastline and the course of Endeavour.1 At 6 a.m., officer of the watch Lieutenant Zachary Today’s maps show Point Hicks, the former Cape Everard, Hickes was the first to see a huge arc of land, apparently as a land feature on the eastern coast of Victoria, but this extending from the NE through to just S of W. At 8 is not, as so many people still believe, the point that Cook a.m. Cook’s journal records that he observed the same ‘saw’. At Cook’s 8 a.m. position it would certainly have arc of land and named the ‘southermost land we had been the closest real land, but because of the curvature in sight which bore from us W ¼ S’ Point Hicks. The of the earth Endeavour would have been too far out to southernmost land was at the western extent of the arc, sea for today’s Point Hicks to be seen. Cook would have but unfortunately for Cook what he saw in this direction seen the higher land behind it, and this was his first real was not land at all, but a cloudbank. -

The Mystery of the Deadwater Wreck

The Mystery of the Deadwater Wreck By Rupert Gerritsen Abstract Historical research indicates there may be the remains of a 17th century Dutch shipwreck in part of an estuarine system in the south west of Western Australia. A variety of highly credible informants described the wreck in the 19th century, yet is seems to have ‘disappeared’. This paper endeavours to explain what happened to the wreck, why it ‘disappeared’ and where it is now. In 1611, as the Dutch were building their trading empire in the East Indies, one of the captains of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC), Hendrik Brouwer, tested out the idea that the Indies could be reached more quickly and easily by sailing due east from the Cape of Good Hope, following the Roaring Forties across the southern Indian Ocean, and then turning north to make for Java. The experiment was a great success, it halved the time such voyages took, and in 1616 the VOC officially adopted the ‘Brouwer Route’ and instructed their captains to follow it. Unbeknownst to them, the Brouwer Route took them very close to the west coast of Australia. At that time all that was known of Australia was 250 kilometres of the west side of Cape York in northern Australia, charted by Willem Janszoon in the Duyfken in 1606. Following the Brouwer Route, Dutch ships soon began encountering the west coast of Australia, the first being Dirk Hartog in the Eeendracht in 1616. Hartog landed at Point Inscription on 25 October 1616 and left behind an inscribed pewter plate, now held by the Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands, signifying his historic ‘discovery’. -

Aboriginal Fish Hooks in Southern Australia : Evidence, Arguments and Implications

Aboriginal fish hooks in southern Australia : Evidence, arguments and implications. Rupert Gerritsen From time to time, in the wanderings of my imagination, I mull over the question of what should be my first course of action if I were the proverbial Martian archaeologist (Jones and Bowler 1980:26), just arrived on Earth to investigate its peoples, cultures and history. And in this imaginary quest, I ask myself, would my time be more productively spent observing and interrogating the "natives", or simply heading for the nearest rubbish dump to begin immediate excavations, a la Rathje (1974)? But, having chose the latter, what then would I make of such things, in my putative excavations, as discarded "lava lamps", "fluffy dice" or garden gnomes? Phallic symbols perhaps, ear-muffs for protection from "rap" music, maybe cult figurines! While such musings are, of course, completely frivolous, nevertheless a serious issue lies at their heart, the interface between ethnography and archaeology. In this scenario the choice faced by the alien archaeologist is clearly a false dichotomy. We are not faced with an either/or situation and I think it unlikely, in the current multidisciplinary climate, that anyone today would seriously argue for precedence of one discipline over the other. In basic terms both disciplines make significant contributions to our understanding of Australian prehistory (Bowdler 1983:135), each providing a body of evidence from which models, theories and explanations are developed. Archaeology, for example, provides invaluable time depth and a spatial dimension in studies of change and development in cultures, whereas ethnography puts flesh on the bones of cultures, revealing their intrinsic complexity and contextualising archaeological findings in the process. -

Zootaxa 2329: 37–55 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (Print Edition) Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (Online Edition)

Zootaxa 2329: 37–55 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) The deep-sea scavenging genus Hirondellea (Crustacea: Amphipoda: Lysianassoidea: Hirondelleidae fam. nov.) in Australian waters J.K. LOWRY & H.E. STODDART Crustacea Section, Australian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney, New South Wales, 2010, Australia ([email protected], [email protected]) Abstract The new lysianassoid amphipod family Hirondelleidae is established and the deep-sea scavenging genus Hirondellea is reported from Australian waters for the first time. Five new species are described: H. diamantina sp. nov.; H. endeavour sp. nov.; H. franklin sp. nov.; H. kapala sp. nov.; and H. naturaliste sp. nov. Anonyx wolfendeni Tattersall is transferred into Hirondellea. Key words: Crustacea, Amphipoda, Hirondelleidae, Australia, taxonomy, new species, Hirondellea diamantina, Hirondellea endeavour, Hirondellea franklin, Hirondellea kapala, Hirondellea naturaliste, Hirondellea wolfendeni Introduction The hirondelleids are a world-wide group of deep-sea scavenging lysianassoid amphipods. There are currently 16 species in the family, but as the deep-sea is explored further it is highly likely that more species will be described. Based on their mouthpart morphology hirondelleids appear to be unspecialised scavengers whose relationship to other members of the lysianassoid group is not clear. In this paper we establish the family Hirondelleidae, report hirondelleids from Australian waters for the first time and describe five new species. We also transfer Anonyx wolfendeni Tattersall, 1909 into Hirondellea. Materials and methods The descriptions were generated from a DELTA database (Dallwitz 2005) to the hirondelleid species of the world. -

Croajingolong National Park Management Plan

National Parks Service Croajingolong National Park Management Plan June 1996 NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT This Management Plan for Croajingolong National Park is approved for implementation. Its purpose is to direct all aspects of management in the Park until the Plan is reviewed. A Draft Management Plan was published in June 1993. A total of 36 submissions were received. Copies of the Plan can be obtained from: Cann River Information Centre Department of Natural Resources and Environment Princes Highway CANN RIVER VIC 3809 Information Centre Department of Natural Resources and Environment 240 Victoria Parade EAST MELBOURNE VIC 3002 Further information on this Plan can be obtained from the NRE Cann River office (051) 586 370. CROAJINGOLONG NATIONAL PARK MANAGEMENT PLAN National Parks Service DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT VICTORIA JUNE 1996 ã Crown (State of Victoria) 1996 A Victorian Government Publication This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1986. Published June 1996 by the Department of Natural Resources and Environment 240 Victoria Parade, East Melbourne, Victoria 3002. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Victoria. National Parks Service. Croajingolong National Park management plan. Bibliography. ISBN 0 7306 6137 7. 1. Croajingolong National Park (Vic.). 2. National parks and reserves - Victoria - Gippsland - Management. I. Victoria. Dept of Natural Resources and Environment. II. Title. 333.783099456 Note: In April 1996 the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (CNR) became part of the Department of Natural Resources and Environment (NRE). Cover: Looking east from Rame Head (photograph K. -

Cook's Point Hicks

DECEMBER 2019 Newsletter of the Australian National Placenames Survey an initiative of the Australian Academy of Humanities, supported by the Geographical Names Board of NSW Cook’s Point Hicks~~a toponymic torment? An earlier article concerning the whereabouts of Lt James the evidence, this view still persists. Cook’s Point Hicks appeared in Placenames Australia in For too long misunderstanding has surrounded the September 2014. It reviewed the evidence and theories location of Point Hicks, the first placename that Cook put forward to explain why Cook had placed it out at bestowed on the coast of Australia. As the navigator sea and some miles from land. It concluded that the approached this coast for idea that Cape Everard the first time at 8 a.m. was Cook’s Point Hicks on 20 April 1770, he was incorrect, and that named what he believed Cook had in fact been was a land feature out to deceived by cloudbanks the west as Point Hicks. which appeared to be Lt Zachary Hicks was real land. To confuse the officer of the watch matters further, against and had made this first all the evidence, in 1970, sighting. Cook recorded to commemorate the the estimated position Bicentenary of Cook’s of Point Hicks as 38.0 S voyage, the government of and 211.07 W, a point Victoria had unhelpfully well out to sea from renamed Cape Everard as the actual coast. Later Point Hicks. navigators assumed from Since then, further their own experience research has revealed that that Cook had mistaken the notion that Cape Figure 1. -

Voyage of the Beagle to Western Australia 1837-43 and Her Commanders' Knowledge of Two VOC Wrecks Report to the Western Austr

Voyage of the Beagle to Western Australia 1837-43 and her commanders’ knowledge of two VOC wrecks Report to the Western Australian Museum Justin Reay FSA FRHistS 1 Report—Department of Maritime Archaeology, Western Australian Maritime Museum: No. 314 1 Justin Reay is a senior manager of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, a tutor in naval history for the University’s international programmes, an advisor to many organisations on maritime history and marine art, and is a member of the Council of the Society for Nautical Research 1 Introduction The writer was asked by the Western Australian Museum to advise on an aspect of the survey cruise of the Beagle around Australia between 1837 and 1843. The issue concerned was the knowledge and sources of that knowledge held by the commander of His Majesty’s Surveying Sloop Beagle, John Wickham, and the vessel’s senior Lieutenant John Stokes, about two merchant ships of the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (Dutch East India Company – the VOC) which were wrecked on the Houtman's Abrolhos, a large archipelago of coral islands and reefs off the coast of Western Australia. The Western Australian Museum requested the writer to consider four questions: 1. When the Beagle left England in 1837 to carry out the survey, what information did Wickham and Stokes have about the Batavia and the Zeewijk? 2. Where did this information come from? 3. Are there any extant logs or journals which could give more information about their findings, particularly any notes about the ship's timbers discovered on 6 April 1840? 4. -

Matthew Flinders and the Quest for a Strait

Australian Historical Studies ISSN: 1031-461X (Print) 1940-5049 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rahs20 A Historical Myth? Matthew Flinders and the Quest for a Strait Kenneth Morgan To cite this article: Kenneth Morgan (2017) A Historical Myth? Matthew Flinders and the Quest for a Strait, Australian Historical Studies, 48:1, 52-67, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2016.1250791 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/1031461X.2016.1250791 © 2017 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 01 Mar 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 449 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rahs20 A Historical Myth? Matthew Flinders and the Quest for a Strait KENNETH MORGAN This article takes issue with a recent argument, made by the late Rupert Gerritsen, that Matthew Flinders deliberately concocted a myth about a north–south strait dividing Australia in order to gain the attention and patronage of Sir Joseph Banks to support the first circumnavigation of Terra Australis in HMS Investigator in 1801–3. This article argues that Flinders did not create a myth but based his arguments on contemporary views that such a dividing strait might exist, backed up with cartographic evidence. Flinders’ achievements in connection with the circumnavigation reflected the analytical mind that led him to search for a strait. On 6 September 1800, the young naval lieutenant Matthew Flinders wrote the most important letter of his career when he contacted Sir Joseph Banks, the Pre- sident of the Royal Society, the most prestigious scientific body in Britain, about the possibility of a large-scale expedition to survey Australia’s coastline.