Ram Head ~ Cook's First Australian Toponym

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cetaceans of South-West England

CETACEANS OF SOUTH-WEST ENGLAND This region encompasses the Severn Estuary, Bristol Channel and the English Channel east to Seaton on the South Devon/Dorset border. The waters of the Western Approaches of the English Channel are richer in cetaceans than any other part of southern Britain. However, the diversity and abundance declines as one goes eastwards in the English Channel and towards the Severn Estuary. Seventeen species of cetacean have been recorded in the South-west Approaches since 1980; nine of these species (32% of the 28 UK species) are present throughout the year or recorded annually as seasonal visitors. Thirteen species have been recorded along the Channel coast or in nearshore waters (within 60 km of the coast) of South-west England. Seven of these species (25% of the 28 UK species) are present throughout the year or are recorded annually. Good locations for nearshore cetacean sightings are prominent headlands and bays. Since 1990, bottlenose dolphins have been reported regularly nearshore, the majority of sightings coming from Penzance Bay, around the Land’s End Peninsula, and St. Ives Bay in Cornwall, although several locations along both north and south coasts of Devon are good for bottlenose dolphin. Cetaceans can also been seen in offshore waters. The main species that have been recorded include short- beaked common dolphins and long-finned pilot whales. Small numbers of harbour porpoises occur annually particularly between October and March off the Cornish & Devon coasts. CETACEAN SPECIES REGULARLY SIGHTED IN THE REGION Fin whale Balaenoptera physalus Rarer visitors to offshore waters, fin whales have been sighted mainly between June and December along the continental shelf edge at depths of 500-3000m. -

INTRUDERS ARRIVE 50,000 Years Ago 1616 1770

© Lonely Planet 33 History Dr Michael Cathcart INTRUDERS ARRIVE By sunrise the storm had passed. Zachary Hicks was keeping sleepy watch on the British ship Endeavour when suddenly he was wide awake. He sum- Dr Michael Cathcart moned his captain, James Cook, who climbed into the brisk morning air wrote the History to a miraculous sight. Ahead of them lay an uncharted country of wooded chapter. Michael teaches hills and gentle valleys. It was 19 April 1770. In the coming days Cook history at the Australian began to draw the first European map of Australia’s eastern coast. He was Centre, the University of mapping the end of Aboriginal supremacy. Melbourne. He is well Two weeks later Cook led a party of men onto a narrow beach. As known as a broadcaster they waded ashore, two Aboriginal men stepped onto the sand, and chal- on ABC Radio National lenged the intruders with spears. Cook drove the men off with musket and presented history fire. For the rest of that week, the Aborigines and the intruders watched programs on ABC TV. For each other warily. more information about Cook’s ship Endeavour was a floating annexe of London’s leading sci- Michael, see p1086. entific organisation, the Royal Society. The ship’s gentlemen passengers included technical artists, scientists, an astronomer and a wealthy bota- nist named Joseph Banks. As Banks and his colleagues strode about the Aborigines’ territory, they were delighted by the mass of new plants they collected. (The showy banksia flowers, which look like red, white or golden bottlebrushes, are named after Banks.) The local Aborigines called the place Kurnell, but Cook gave it a foreign name: he called it ‘ Botany Bay’. -

The Great Barrier Reef History, Science, Heritage

The Great Barrier Reef History, Science, Heritage One of the world’s natural wonders, the Great Barrier Reef stretches more than 2000 kilo- metres in a maze of coral reefs and islands along Australia’s north-eastern coastline. This book unfolds the fascinating story behind its mystique, providing for the first time a comprehensive cultural and ecological history of European impact, from early voyages of discovery to the most recent developments in Reef science and management. Incisive and a delight to read in its thorough account of the scientific, social and environmental consequences of European impact on the world’s greatest coral reef system and Australia’s greatest natural feature, this extraordinary book is sure to become a classic. After graduating from the University of Sydney and completing a PhD at the University of Illinois, James Bowen pursued an academic career in the United States, Canada and Australia, publishing extensively in the history of ideas and environmental thought. As visiting Professorial Fellow at the Australian National University from 1984 to 1989, he became absorbed in the complex history of the Reef, exploring this over the next decade through intensive archival, field and underwater research in collaboration with Margarita Bowen, ecologist and distinguished historian of science. The outcome of those stimulating years is this absorbing saga. To our grandchildren, with hope for the future in the hands of their generation The Great Barrier Reef History, Science, Heritage JAMES BOWEN AND MARGARITA BOWEN Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , United Kingdom Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521824309 © James Bowen & Margarita Bowen 2002 This book is in copyright. -

EIS 1767 AA066857 Assessment of Mineral Resouru's in the Eden CRA

EIS 1767 AA066857 Assessment of mineral resouru's in the Eden CRA study area MSW DEPT P1KARY IUS1RIES AA066857 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 :0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ( 0 0 0 0 0 I 0 ( 0 I I I I I Assessment of Mineral Resources in the Eden CRA Study Area A report undertaken for the NSW CRAIRFA Steering Committee 27 February 1998 ASSESSMENT OF MINERAL RESOURCES IN THE EDEN CRA STUDY AREA BUREAU OF RESOURCE SCIENCES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF NSW DEPARTMENT OF MINERAL RESOURCES A report undertaken for the NSW CRA/RFA Steering Committee Project Number NE 08/ES 27 February 1998 REPORT STATUS This report has been prepared as a working paper for the NSW CRAIRFA Steering Committee under the direction of the Economic and Social Technical Committee. It is recognised that it may contain errors that require correction but it is released to be consistent with the principle that information related to the comprehensive regional assessment process in New South Wales will be made publicly available. For more information and for information on access to data contact the: Resource and Conservation Division, Department of Urban Affairs and Planning GPO Box 3927 SYDNEY NSW 2001 Phone: (02) 9228 3166 Fax: (02) 9228 4967 Forests Taskforce, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet 3-5 National Circuit BARTON ACT 2600 Phone: 1800 650 983 Fax: (02) 6271 5511 © Crown copyright [June 1997] This project has been jointly funded by the New South Wales and Commonwealth Governments. The work undertaken within this project has been managed by the joint NSW / Commonwealth CRAIRFA Steering Committee which includes representatives from the NSW and Commonwealth Governments and stakeholder groups. -

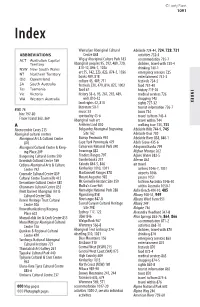

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

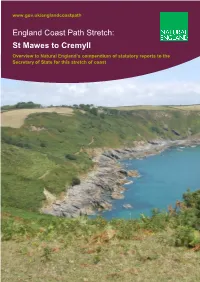

St Mawes to Cremyll Overview to Natural England’S Compendium of Statutory Reports to the Secretary of State for This Stretch of Coast

www.gov.uk/englandcoastpath England Coast Path Stretch: St Mawes to Cremyll Overview to Natural England’s compendium of statutory reports to the Secretary of State for this stretch of coast 1 England Coast Path | St Mawes to Cremyll | Overview Map A: Key Map – St Mawes to Cremyll 2 England Coast Path | St Mawes to Cremyll | Overview Report number and title SMC 1 St Mawes to Nare Head (Maps SMC 1a to SMC 1i) SMC 2 Nare Head to Dodman Point (Maps SMC 2a to SMC 2h) SMC 3 Dodman Point to Drennick (Maps SMC 3a to SMC 3h) SMC 4 Drennick to Fowey (Maps SMC 4a to SMC 4j) SMC 5 Fowey to Polperro (Maps SMC 5a to SMC 5f) SMC 6 Polperro to Seaton (Maps SMC 6a to SMC 6g) SMC 7 Seaton to Rame Head (Maps SMC 7a to SMC 7j) SMC 8 Rame Head to Cremyll (Maps SMC 8a to SMC 8f) Using Key Map Map A (opposite) shows the whole of the St Mawes to Cremyll stretch divided into shorter numbered lengths of coast. Each number on Map A corresponds to the report which relates to that length of coast. To find our proposals for a particular place, find the place on Map A and note the number of the report which includes it. If you are interested in an area which crosses the boundary between two reports, please read the relevant parts of both reports. Printing If printing, please note that the maps which accompany reports SMC 1 to SMC 8 should ideally be printed on A3 paper. -

Secrets of Millbrook

SECRETS OF MILLBROOK History of Cornwall History of Millbrook Hiking Places of interest Pubs and Restaurants Cornish food Music and art Dear reader, We are a German group which created this Guide book for you. We had lots of fun exploring Millbrook and the Rame peninsula and want to share our discoveries with you on the following pages. We assembled a selection of sights, pubs, café, restaurants, history, music and arts. We would be glad, if we could help you and we wish you a nice time in Millbrook Your German group Karl Jorma Ina Franziska 1 Contents Page 3 Introduction 4 History of Cornwall 6 History of Millbrook The Tide Mill Industry around Millbrook 10 Smuggling 11 Fishing 13 Hiking and Walking Mount Edgcumbe House The Maker Church Penlee Point St. Michaels Chapel Rame Church St. Germanus 23 Eden Project 24 The Minack Theatre 25 South West Coast 26 Beaches on the Rame peninsula 29 Millbrook’s restaurants & cafes 32 Millbrook’s pubs 34 Cornish food 36 Music & arts 41 Point Europa 42 Acknowledgments 2 Millbrook, or Govermelin as it is called in the Cornish language, is the biggest village in Cornwall and located in the centre of the Rame peninsula. The current population of Millbrook is about 2300. Many locals take the Cremyll ferry or the Torpoint car ferry across Plymouth Sound to go to work, while others are employed locally by boatyards, shops and restaurants. The area also attracts many retirees from cities all around Britain. Being situated at the head of a tidal creek, the ocean has always had a major influence on life in Millbrook. -

The Discovery and Mapping of Australia's Coasts

Paper 1 The Discovery and Mapping of Australia’s Coasts: the Contribution of the Dutch, French and British Explorer- Hydrographers Dorothy F. Prescott O.A.M [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper focuses on the mapping of Australia’s coasts resulting from the explorations of the Dutch, French and English hydrographers. It leaves untouched possible but unproven earlier voyages for which no incontrovertible evidence exists. Beginning with the voyage of the Dutch yacht, Duyfken, in 1605-6 it examines the planned voyages to the north coast and mentions the more numerous accidental landfalls on the west coast of the continent during the early decades of the 1600s. The voyages of Abel Tasman and Willem de Vlamingh end the period of successful Dutch visitations to Australian shores. Following James Cook’s discovery of the eastern seaboard and his charting of the east coast, further significant details to the charts were added by the later expeditions of Frenchmen, D’Entrecasteaux and Baudin, and the Englishmen, Bass and Flinders in 1798. Further work on the east coast was carried out by Flinders in 1799 and from 1801 to 1803 during his circumnavigation of the continent. The final work of completing the charting of the entire coastline was carried out by Phillip Parker King, John Clements Wickham and John Lort Stokes. It was Stokes who finally proved the death knell for the theory fondly entertained by the Admiralty of a great river flowing from the centre of the continent which would provide a highroad to the interior. Stokes would spend 6 years examining all possible river openings without the hoped- for result. -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

The Lees of Quethiock Cornwall Their Family History from Ancient Times

THE LEES OF QUETHIOCK CORNWALL THEIR FAMILY HISTORY FROM ANCIENT TIMES "Brave men have lived before Agamemnon, lots of them. But on all of them - eternal night lies heavy, for they left no records behind. (`ODES` Horace 65-8BC) This is the story of those who did This is the story of my ancestors, the Lee family, who have left records behind and from which the line can be traced from Alexander and Thomas born 1994 and 1990 respectively, back to John of Legh, alive in 1433, and Richard de Leye, alive in 1327. John and Richard lived at, and took their surname from Legh, a pre-Norman settlement in Cornwall recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086. Legh is situated in the present parish of Quethiock, some 5 miles west of the River Tamar and 5 miles east of Liskeard, just in the southeast corner of Cornwall. To uncover the history took ten and more years of research. So what stimulated me to commence? In 1986 I watched a television programme on early portraiture. It was explained that during the time of the Roman Empire (146BC-410AD) it was fashionable to have a statue carved of oneself together with ones father and grandfather. To illustrate this a statue from the 1st century AD was shown; I was astounded to note that it bore a likeness to my family and in particular to my brother, David Henry Lee. I immediately commented on this to my wife, Brenda, who replied `No, it is more like you`. From that moment the question lay in my mind `I look like a Roman from 2000 years ago; I have the surname of Lee which is derived from a Saxon-German word meaning pasture; my father`s family were known to have come from Cornwall and so presumably I have West Welsh Celtic blood; my mother claimed her family came from Devon and I was born in Devonport on the borders of Devon and Cornwall; so who am I? Cornwall over the millenniums had been invaded by 6 or so groups of different people; Ancient British (7000BC), Celts (700BC-63AD), Danes (800AD), Romans (63-401AD), Saxons (447-1066AD), Normans (1066). -

Appendix 1 - Fish Species Occurrence in NSW River Drainage Basins 271

Appendix 1 - Fish species occurrence in NSW River Drainage Basins 271 Appendix 1 - Fish species occurrence in NSW River Drainage Basins Table 1 Fish species recorded in the Richmond River drainage basin (DWR catchment code 203) in the NSW Rivers Survey ("1996 Survey") and a previous study (Llewellyn 1983)("1983 Survey"). Site code Site name Stream Nearest town NCRL46 Casino Richmond River Casino NCRL50 Dunoon Rocky Creek Lismore NCRL48 Tintenbar Emigrant Creek Tintenbar NCUL60 Lismore Leycester Creek Lismore Species 1996 Survey* 1983 Survey Acanthopagrus australis 10 Ambassis agassizii 10 Ambassis nigripinnis 11 Anguilla australis 01 Anguilla reinhardtii 10 Arius graeffei 10 Arrhamphus sclerolepis 10 Carcharhinus leucas 10 Gambusia holbrooki 11 Gnathanodon speciosus 10 Gobiomorphus australis 11 Gobiomorphus coxii 01 Herklotsichthys castelnaui 10 Hypseleotris compressa 11 Hypseleotris galii 11 Hypseleotris spp 1 0 Liza argentea 10 Macquaria colonorum 10 Macquaria novemaculeata 10 Melanotaenia duboulayi 11 Mugil cephalus 11 Myxus petardi 11 Notesthes robusta 11 Philypnodon grandiceps 10 Philypnodon sp1 1 0 Platycephalus fuscus 10 Potamalosa richmondia 10 Pseudomugil signifer 11 Retropinna semoni 11 Tandanus tandanus 11 Total 28 14 *1 - Species recorded, 0 - Species not recorded (Details of fish records at individual sites and times are given in Harris et al. (1996). CRC For Freshwater Ecology RACAC NSW Fisheries 272 NSW Rivers Survey Table 2 Fish species recorded in the Clarence River drainage basin (DWR catchment code 204) in the NSW Rivers -

Point Hicks (Cape Everard) James Cook's Australian Landfall

SEPTEMBER 2014 Newsletter of the Australian National Placenames Survey an initiative of the Australian Academy of Humanities, supported by the Geographical Names Board of NSW Point Hicks (Cape Everard) James Cook's Australian landfall Early in the morning of 19 April 1770 Lieutenant Cook 12 miles from the nearest land. Map 1 (page 6, below) and the crew of Endeavour had their first glimpses of the shows the coast as laid down by Cook, the modern Australian continent on the far eastern coast of Victoria. coastline and the course of Endeavour.1 At 6 a.m., officer of the watch Lieutenant Zachary Today’s maps show Point Hicks, the former Cape Everard, Hickes was the first to see a huge arc of land, apparently as a land feature on the eastern coast of Victoria, but this extending from the NE through to just S of W. At 8 is not, as so many people still believe, the point that Cook a.m. Cook’s journal records that he observed the same ‘saw’. At Cook’s 8 a.m. position it would certainly have arc of land and named the ‘southermost land we had been the closest real land, but because of the curvature in sight which bore from us W ¼ S’ Point Hicks. The of the earth Endeavour would have been too far out to southernmost land was at the western extent of the arc, sea for today’s Point Hicks to be seen. Cook would have but unfortunately for Cook what he saw in this direction seen the higher land behind it, and this was his first real was not land at all, but a cloudbank.