Cook's Point Hicks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTRUDERS ARRIVE 50,000 Years Ago 1616 1770

© Lonely Planet 33 History Dr Michael Cathcart INTRUDERS ARRIVE By sunrise the storm had passed. Zachary Hicks was keeping sleepy watch on the British ship Endeavour when suddenly he was wide awake. He sum- Dr Michael Cathcart moned his captain, James Cook, who climbed into the brisk morning air wrote the History to a miraculous sight. Ahead of them lay an uncharted country of wooded chapter. Michael teaches hills and gentle valleys. It was 19 April 1770. In the coming days Cook history at the Australian began to draw the first European map of Australia’s eastern coast. He was Centre, the University of mapping the end of Aboriginal supremacy. Melbourne. He is well Two weeks later Cook led a party of men onto a narrow beach. As known as a broadcaster they waded ashore, two Aboriginal men stepped onto the sand, and chal- on ABC Radio National lenged the intruders with spears. Cook drove the men off with musket and presented history fire. For the rest of that week, the Aborigines and the intruders watched programs on ABC TV. For each other warily. more information about Cook’s ship Endeavour was a floating annexe of London’s leading sci- Michael, see p1086. entific organisation, the Royal Society. The ship’s gentlemen passengers included technical artists, scientists, an astronomer and a wealthy bota- nist named Joseph Banks. As Banks and his colleagues strode about the Aborigines’ territory, they were delighted by the mass of new plants they collected. (The showy banksia flowers, which look like red, white or golden bottlebrushes, are named after Banks.) The local Aborigines called the place Kurnell, but Cook gave it a foreign name: he called it ‘ Botany Bay’. -

The Great Barrier Reef History, Science, Heritage

The Great Barrier Reef History, Science, Heritage One of the world’s natural wonders, the Great Barrier Reef stretches more than 2000 kilo- metres in a maze of coral reefs and islands along Australia’s north-eastern coastline. This book unfolds the fascinating story behind its mystique, providing for the first time a comprehensive cultural and ecological history of European impact, from early voyages of discovery to the most recent developments in Reef science and management. Incisive and a delight to read in its thorough account of the scientific, social and environmental consequences of European impact on the world’s greatest coral reef system and Australia’s greatest natural feature, this extraordinary book is sure to become a classic. After graduating from the University of Sydney and completing a PhD at the University of Illinois, James Bowen pursued an academic career in the United States, Canada and Australia, publishing extensively in the history of ideas and environmental thought. As visiting Professorial Fellow at the Australian National University from 1984 to 1989, he became absorbed in the complex history of the Reef, exploring this over the next decade through intensive archival, field and underwater research in collaboration with Margarita Bowen, ecologist and distinguished historian of science. The outcome of those stimulating years is this absorbing saga. To our grandchildren, with hope for the future in the hands of their generation The Great Barrier Reef History, Science, Heritage JAMES BOWEN AND MARGARITA BOWEN Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , United Kingdom Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521824309 © James Bowen & Margarita Bowen 2002 This book is in copyright. -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

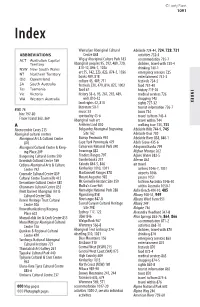

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Water Research Laboratory

Water Research Laboratory Never Stand Still Faculty of Engineering School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Eurobodalla Coastal Hazard Assessment WRL Technical Report 2017/09 October 2017 by I R Coghlan, J T Carley, A J Harrison, D Howe, A D Short, J E Ruprecht, F Flocard and P F Rahman Project Details Report Title Eurobodalla Coastal Hazard Assessment Report Author(s) I R Coghlan, J T Carley, A J Harrison, D Howe, A D Short, J E Ruprecht, F Flocard and P F Rahman Report No. 2017/09 Report Status Final Date of Issue 16 October 2017 WRL Project No. 2014105.01 Project Manager Ian Coghlan Client Name 1 Umwelt Australia Pty Ltd Client Address 1 75 York Street PO Box 3024 Teralba NSW 2284 Client Contact 1 Pam Dean-Jones Client Name 2 Eurobodalla Shire Council Client Address 2 89 Vulcan Street PO Box 99 Moruya NSW 2537 Client Contact 2 Norman Lenehan Client Reference ESC Tender IDs 216510 and 557764 Document Status Version Reviewed By Approved By Date Issued Draft J T Carley G P Smith 9 June 2017 Final Draft J T Carley G P Smith 1 September 2017 Final J T Carley G P Smith 16 October 2017 This report was produced by the Water Research Laboratory, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of New South Wales for use by the client in accordance with the terms of the contract. Information published in this report is available for release only with the permission of the Director, Water Research Laboratory and the client. It is the responsibility of the reader to verify the currency of the version number of this report. -

FF Directory

Directory WFF (World Flora Fauna Program) - Updated 30 November 2012 Directory WorldWide Flora & Fauna - Updated 30 November 2012 Release 2012.06 - by IK1GPG Massimo Balsamo & I5FLN Luciano Fusari Reference Name DXCC Continent Country FF Category 1SFF-001 Spratly 1S AS Spratly Archipelago 3AFF-001 Réserve du Larvotto 3A EU Monaco 3AFF-002 Tombant à corail des Spélugues 3A EU Monaco 3BFF-001 Black River Gorges 3B8 AF Mauritius I. 3BFF-002 Agalega is. 3B6 AF Agalega Is. & St.Brandon I. 3BFF-003 Saint Brandon Isls. (aka Cargados Carajos Isls.) 3B7 AF Agalega Is. & St.Brandon I. 3BFF-004 Rodrigues is. 3B9 AF Rodriguez I. 3CFF-001 Monte-Rayses 3C AF Equatorial Guinea 3CFF-002 Pico-Santa-Isabel 3C AF Equatorial Guinea 3D2FF-001 Conway Reef 3D2 OC Conway Reef 3D2FF-002 Rotuma I. 3D2 OC Conway Reef 3DAFF-001 Mlilvane 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3DAFF-002 Mlavula 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3DAFF-003 Malolotja 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3VFF-001 Bou-Hedma 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-002 Boukornine 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-003 Chambi 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-004 El-Feidja 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-005 Ichkeul 3V AF Tunisia National Park, UNESCO-World Heritage 3VFF-006 Zembraand Zembretta 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-007 Kouriates Nature Reserve 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-008 Iles de Djerba 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-009 Sidi Toui 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-010 Tabarka 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-011 Ain Chrichira 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-012 Aina Zana 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-013 des Iles Kneiss 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-014 Serj 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-015 Djebel Bouramli 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-016 Djebel Khroufa 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-017 Djebel Touati 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-018 Etella Natural 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-019 Grotte de Chauve souris d'El Haouaria 3V AF Tunisia National Park, UNESCO-World Heritage 3VFF-020 Ile Chikly 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-021 Kechem el Kelb 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-022 Lac de Tunis 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-023 Majen Djebel Chitane 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-024 Sebkhat Kelbia 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-025 Tourbière de Dar. -

Contested Borders - Is Cook's Cape Howe Really Telegraph Point?

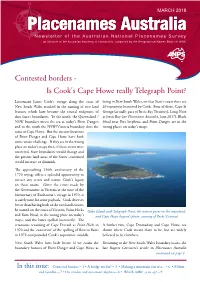

MARCH 2018 Newsletter of the Australian National Placenames Survey an initiative of the Australian Academy of Humanities, supported by the Geographical Names Board of NSW Contested borders - Is Cook's Cape Howe really Telegraph Point? Lieutenant James Cook's voyage along the coast of being in New South Wales, on that State's coast there are New South Wales resulted in the naming of two land 26 toponyms bestowed by Cook. Four of these, Cape St features which later became the coastal endpoints of George (actually part of Jervis Bay Territory), Long Nose that State’s boundaries. To the north, the Queensland / at Jervis Bay (see Placenames Australia, June 2017), Black NSW boundary meets the sea at today's Point Danger, Head near Port Stephens, and Point Danger, are in the and to the south the NSW/Victoria boundary does the wrong places on today's maps. same at Cape Howe. But the current locations of Point Danger and Cape Howe have both come under challenge. If they are in the wrong place on today's maps then, if these errors were corrected, State boundaries would change and the present land areas of the States concerned would increase or diminish. The approaching 250th anniversary of the 1770 voyage offers a splendid opportunity to correct any errors and restore Cook's legacy on these coasts. Given the errors made by the Government in Victoria at the time of the bicentenary of Endeavour's voyage in 1970, it is surely time for some payback. Cook deserves better than having both of the two land features he named on the coast of Victoria, Point Hicks Gabo Island with Telegraph Point, the nearest point on the mainland, and Ram Head, in the wrong place on today's and Cape Howe beyond (photo: courtesy of Parks Victoria) maps, and the latter spelled incorrectly. -

The Discovery and Mapping of Australia's Coasts

Paper 1 The Discovery and Mapping of Australia’s Coasts: the Contribution of the Dutch, French and British Explorer- Hydrographers Dorothy F. Prescott O.A.M [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper focuses on the mapping of Australia’s coasts resulting from the explorations of the Dutch, French and English hydrographers. It leaves untouched possible but unproven earlier voyages for which no incontrovertible evidence exists. Beginning with the voyage of the Dutch yacht, Duyfken, in 1605-6 it examines the planned voyages to the north coast and mentions the more numerous accidental landfalls on the west coast of the continent during the early decades of the 1600s. The voyages of Abel Tasman and Willem de Vlamingh end the period of successful Dutch visitations to Australian shores. Following James Cook’s discovery of the eastern seaboard and his charting of the east coast, further significant details to the charts were added by the later expeditions of Frenchmen, D’Entrecasteaux and Baudin, and the Englishmen, Bass and Flinders in 1798. Further work on the east coast was carried out by Flinders in 1799 and from 1801 to 1803 during his circumnavigation of the continent. The final work of completing the charting of the entire coastline was carried out by Phillip Parker King, John Clements Wickham and John Lort Stokes. It was Stokes who finally proved the death knell for the theory fondly entertained by the Admiralty of a great river flowing from the centre of the continent which would provide a highroad to the interior. Stokes would spend 6 years examining all possible river openings without the hoped- for result. -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

From Catchment to Inner Shelf: Insights Into NSW Coastal Compartments

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 1-1-2015 From catchment to inner shelf: insights into NSW coastal compartments Rafael Cabral Carvalho University of Wollongong, [email protected] Colin D. Woodroffe University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cabral Carvalho, Rafael and Woodroffe, Colin D., "From catchment to inner shelf: insights into NSW coastal compartments" (2015). Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A. 4632. https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers/4632 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] From catchment to inner shelf: insights into NSW coastal compartments Abstract This paper addresses the coastal compartments of the eastern coast by analysing characteristics of the seven biggest catchments in NSW (Shoalhaven, Hawkesbury, Hunter, Manning, Macleay, Clarence and Richmond) and coastal landforms such as estuaries, sand barriers, beaches, headlands, nearshore and inner shelf, providing a framework for estimating sediment budgets by delineating compartment boundaries and defining management units. It sheds light on the sediment dispersal yb rivers and longshore drift by reviewing literature, using available information/data, and modelling waves and sediment dispersal. Compartments were delineated based on physical characteristics through interpretation of hydrologic, geomorphic, geophysical, sedimentological, oceanographic factors and remote sensing. Results include identification of 36 primary compartments along the NSW coast, 80 secondary compartments on the South and Central coast, and 5 tertiary compartments for the Shoalhaven sector. -

Point Hicks (Cape Everard) James Cook's Australian Landfall

SEPTEMBER 2014 Newsletter of the Australian National Placenames Survey an initiative of the Australian Academy of Humanities, supported by the Geographical Names Board of NSW Point Hicks (Cape Everard) James Cook's Australian landfall Early in the morning of 19 April 1770 Lieutenant Cook 12 miles from the nearest land. Map 1 (page 6, below) and the crew of Endeavour had their first glimpses of the shows the coast as laid down by Cook, the modern Australian continent on the far eastern coast of Victoria. coastline and the course of Endeavour.1 At 6 a.m., officer of the watch Lieutenant Zachary Today’s maps show Point Hicks, the former Cape Everard, Hickes was the first to see a huge arc of land, apparently as a land feature on the eastern coast of Victoria, but this extending from the NE through to just S of W. At 8 is not, as so many people still believe, the point that Cook a.m. Cook’s journal records that he observed the same ‘saw’. At Cook’s 8 a.m. position it would certainly have arc of land and named the ‘southermost land we had been the closest real land, but because of the curvature in sight which bore from us W ¼ S’ Point Hicks. The of the earth Endeavour would have been too far out to southernmost land was at the western extent of the arc, sea for today’s Point Hicks to be seen. Cook would have but unfortunately for Cook what he saw in this direction seen the higher land behind it, and this was his first real was not land at all, but a cloudbank. -

Albany Coast Draft Management Plan 2016

Albany coast draft management plan 2016 Albany coast draft management plan 2016 Conservation Commission of Western Australia Department of Parks and Wildlife Department of Parks and Wildlife 17 Dick Perry Avenue KENSINGTON WA 6151 Phone: (08) 9219 9000 Fax: (08) 9334 0498 www.dpaw.wa.gov.au © State of Western Australia 2016 May 2016 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Department of Parks and Wildlife. ISBN 978-1-921703-67-6 (print) ISBN 978-1-921703-68-3 (online) This management plan was prepared by the Conservation Commission of Western Australia through the agency of the Department of Parks and Wildlife. Questions regarding this management plan should be directed to: Planning Branch Department of Parks and Wildlife Locked Bag 104 Bentley Delivery Centre WA 6983 Phone: (08) 9219 9000 The recommended reference for this publication is: Department of Parks and Wildlife (2016) Albany coast draft management plan 2016. Department of Parks and Wildlife, Perth. This document is available in alternative formats on request. Please note: URLs in this document which conclude a sentence are followed by a full point. If copying the URL please do not include the full point. Front cover photos Main The new recreation facilities at The Gap in Torndirrup National Park. Photo – Parks and Wildlife Top left Gilbert’s potoroo or ngilgyte (Potorous gilberti). -

Reconstructing Aboriginal Economy and Society: the New South Wales

Reconstructing Aboriginal 12 Economy and Society: The New South Wales South Coast at the Threshold of Colonisation John M. White Ian Keen’s 2004 monograph, Aboriginal Economy and Society: Australia at the Threshold of Colonisation, represents the first anthropological study to draw together comparative pre- and postcolonial data sets and sources to explain the nature and variety of Aboriginal economy and society across the Australian continent. Keen’s (2004: 5) rationalisation for comparing the economy and society of seven regions was ‘mainly descriptive and analytical’, in order to ‘shed light on the character of each region, and to bring out their similarities and differences’. In doing so, as Veth (2006: 68) commented in his review of the book, ‘It speaks to meticulous and exhaustive research from myriad sources including social anthropology, linguistics, history, ecology and, not the least, archaeology’. Following its publication, Aboriginal Economy and Society: Australia at the Threshold of Colonisation won Keen his second Stanner Award from the Council of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies in 2005. In this chapter, I draw upon Keen’s comparative method to profile the ecology, institutions and economy of the Yuin people of (what is now) the Eurobodalla region of the New South Wales south coast at the time of European colonisation.1 1 Elsewhere I have documented the role of Aboriginal workers in the New South Wales south coast horticultural sector in the mid-twentieth century (White 2010a, 2010b, 2011) and have detailed the reactions of Yuin people to colonial incursions, which involved the development of intercultural relations that were mediated by exchange (White 2012).