From Catchment to Inner Shelf: Insights Into NSW Coastal Compartments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape York Peninsula Parks and Reserves Visitor Guide

Parks and reserves Visitor guide Featuring Annan River (Yuku Baja-Muliku) National Park and Resources Reserve Black Mountain National Park Cape Melville National Park Endeavour River National Park Kutini-Payamu (Iron Range) National Park (CYPAL) Heathlands Resources Reserve Jardine River National Park Keatings Lagoon Conservation Park Mount Cook National Park Oyala Thumotang National Park (CYPAL) Rinyirru (Lakefield) National Park (CYPAL) Great state. Great opportunity. Cape York Peninsula parks and reserves Thursday Possession Island National Park Island Pajinka Bamaga Jardine River Resources Reserve Denham Group National Park Jardine River Eliot Creek Jardine River National Park Eliot Falls Heathlands Resources Reserve Captain Billy Landing Raine Island National Park (Scientific) Saunders Islands Legend National Park National park Sir Charles Hardy Group National Park Mapoon Resources reserve Piper Islands National Park (CYPAL) Wen Olive River loc Conservation park k River Wuthara Island National Park (CYPAL) Kutini-Payamu Mitirinchi Island National Park (CYPAL) Water Moreton (Iron Range) Telegraph Station National Park Chilli Beach Waterway Mission River Weipa (CYPAL) Ma’alpiku Island National Park (CYPAL) Napranum Sealed road Lockhart Lockhart River Unsealed road Scale 0 50 100 km Aurukun Archer River Oyala Thumotang Sandbanks National Park Roadhouse National Park (CYPAL) A r ch KULLA (McIlwraith Range) National Park (CYPAL) er River C o e KULLA (McIlwraith Range) Resources Reserve n River Claremont Isles National Park Coen Marpa -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

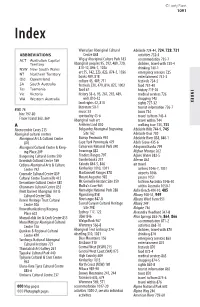

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Water Research Laboratory

Water Research Laboratory Never Stand Still Faculty of Engineering School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Eurobodalla Coastal Hazard Assessment WRL Technical Report 2017/09 October 2017 by I R Coghlan, J T Carley, A J Harrison, D Howe, A D Short, J E Ruprecht, F Flocard and P F Rahman Project Details Report Title Eurobodalla Coastal Hazard Assessment Report Author(s) I R Coghlan, J T Carley, A J Harrison, D Howe, A D Short, J E Ruprecht, F Flocard and P F Rahman Report No. 2017/09 Report Status Final Date of Issue 16 October 2017 WRL Project No. 2014105.01 Project Manager Ian Coghlan Client Name 1 Umwelt Australia Pty Ltd Client Address 1 75 York Street PO Box 3024 Teralba NSW 2284 Client Contact 1 Pam Dean-Jones Client Name 2 Eurobodalla Shire Council Client Address 2 89 Vulcan Street PO Box 99 Moruya NSW 2537 Client Contact 2 Norman Lenehan Client Reference ESC Tender IDs 216510 and 557764 Document Status Version Reviewed By Approved By Date Issued Draft J T Carley G P Smith 9 June 2017 Final Draft J T Carley G P Smith 1 September 2017 Final J T Carley G P Smith 16 October 2017 This report was produced by the Water Research Laboratory, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of New South Wales for use by the client in accordance with the terms of the contract. Information published in this report is available for release only with the permission of the Director, Water Research Laboratory and the client. It is the responsibility of the reader to verify the currency of the version number of this report. -

FF Directory

Directory WFF (World Flora Fauna Program) - Updated 30 November 2012 Directory WorldWide Flora & Fauna - Updated 30 November 2012 Release 2012.06 - by IK1GPG Massimo Balsamo & I5FLN Luciano Fusari Reference Name DXCC Continent Country FF Category 1SFF-001 Spratly 1S AS Spratly Archipelago 3AFF-001 Réserve du Larvotto 3A EU Monaco 3AFF-002 Tombant à corail des Spélugues 3A EU Monaco 3BFF-001 Black River Gorges 3B8 AF Mauritius I. 3BFF-002 Agalega is. 3B6 AF Agalega Is. & St.Brandon I. 3BFF-003 Saint Brandon Isls. (aka Cargados Carajos Isls.) 3B7 AF Agalega Is. & St.Brandon I. 3BFF-004 Rodrigues is. 3B9 AF Rodriguez I. 3CFF-001 Monte-Rayses 3C AF Equatorial Guinea 3CFF-002 Pico-Santa-Isabel 3C AF Equatorial Guinea 3D2FF-001 Conway Reef 3D2 OC Conway Reef 3D2FF-002 Rotuma I. 3D2 OC Conway Reef 3DAFF-001 Mlilvane 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3DAFF-002 Mlavula 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3DAFF-003 Malolotja 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3VFF-001 Bou-Hedma 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-002 Boukornine 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-003 Chambi 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-004 El-Feidja 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-005 Ichkeul 3V AF Tunisia National Park, UNESCO-World Heritage 3VFF-006 Zembraand Zembretta 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-007 Kouriates Nature Reserve 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-008 Iles de Djerba 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-009 Sidi Toui 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-010 Tabarka 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-011 Ain Chrichira 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-012 Aina Zana 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-013 des Iles Kneiss 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-014 Serj 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-015 Djebel Bouramli 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-016 Djebel Khroufa 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-017 Djebel Touati 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-018 Etella Natural 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-019 Grotte de Chauve souris d'El Haouaria 3V AF Tunisia National Park, UNESCO-World Heritage 3VFF-020 Ile Chikly 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-021 Kechem el Kelb 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-022 Lac de Tunis 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-023 Majen Djebel Chitane 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-024 Sebkhat Kelbia 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-025 Tourbière de Dar. -

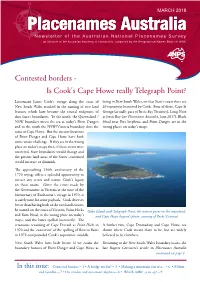

Contested Borders - Is Cook's Cape Howe Really Telegraph Point?

MARCH 2018 Newsletter of the Australian National Placenames Survey an initiative of the Australian Academy of Humanities, supported by the Geographical Names Board of NSW Contested borders - Is Cook's Cape Howe really Telegraph Point? Lieutenant James Cook's voyage along the coast of being in New South Wales, on that State's coast there are New South Wales resulted in the naming of two land 26 toponyms bestowed by Cook. Four of these, Cape St features which later became the coastal endpoints of George (actually part of Jervis Bay Territory), Long Nose that State’s boundaries. To the north, the Queensland / at Jervis Bay (see Placenames Australia, June 2017), Black NSW boundary meets the sea at today's Point Danger, Head near Port Stephens, and Point Danger, are in the and to the south the NSW/Victoria boundary does the wrong places on today's maps. same at Cape Howe. But the current locations of Point Danger and Cape Howe have both come under challenge. If they are in the wrong place on today's maps then, if these errors were corrected, State boundaries would change and the present land areas of the States concerned would increase or diminish. The approaching 250th anniversary of the 1770 voyage offers a splendid opportunity to correct any errors and restore Cook's legacy on these coasts. Given the errors made by the Government in Victoria at the time of the bicentenary of Endeavour's voyage in 1970, it is surely time for some payback. Cook deserves better than having both of the two land features he named on the coast of Victoria, Point Hicks Gabo Island with Telegraph Point, the nearest point on the mainland, and Ram Head, in the wrong place on today's and Cape Howe beyond (photo: courtesy of Parks Victoria) maps, and the latter spelled incorrectly. -

NPWS Annual Report 2000-2001 (PDF

Annual report 2000-2001 NPWS mission NSW national Parks & Wildlife service 2 Contents Director-General’s foreword 6 3 Conservation management 43 Working with Aboriginal communities 44 Overview 8 Joint management of national parks 44 Mission statement 8 Performance and future directions 45 Role and functions 8 Outside the reserve system 46 Partners and stakeholders 8 Voluntary conservation agreements 46 Legal basis 8 Biodiversity conservation programs 46 Organisational structure 8 Wildlife management 47 Lands managed for conservation 8 Performance and future directions 48 Organisational chart 10 Ecologically sustainable management Key result areas 12 of NPWS operations 48 Threatened species conservation 48 1 Conservation assessment 13 Southern Regional Forest Agreement 49 NSW Biodiversity Strategy 14 Caring for the environment 49 Regional assessments 14 Waste management 49 Wilderness assessment 16 Performance and future directions 50 Assessment of vacant Crown land in north-east New South Wales 19 Managing our built assets 51 Vegetation surveys and mapping 19 Buildings 51 Wetland and river system survey and research 21 Roads and other access 51 Native fauna surveys and research 22 Other park infrastructure 52 Threat management research 26 Thredbo Coronial Inquiry 53 Cultural heritage research 28 Performance and future directions 54 Conservation research and assessment tools 29 Managing site use in protected areas 54 Performance and future directions 30 Performance and future directions 54 Contributing to communities 55 2 Conservation planning -

AIA REGISTER Jan 2015

AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS REGISTER OF SIGNIFICANT ARCHITECTURE IN NSW BY SUBURB Firm Design or Project Architect Circa or Start Date Finish Date major DEM Building [demolished items noted] No Address Suburb LGA Register Decade Date alterations Number [architect not identified] [architect not identified] circa 1910 Caledonia Hotel 110 Aberdare Street Aberdare Cessnock 4702398 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] circa 1905 Denman Hotel 143 Cessnock Road Abermain Cessnock 4702399 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1906 St Johns Anglican Church 13 Stoke Street Adaminaby Snowy River 4700508 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Adaminaby Bowling Club Snowy Mountains Highway Adaminaby Snowy River 4700509 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] circa 1920 Royal Hotel Camplbell Street corner Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701604 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1936 Adelong Hotel (Town Group) 67 Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701605 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Adelonia Theatre (Town Group) 84 Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701606 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Adelong Post Office (Town Group) 80 Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701607 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Golden Reef Motel Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701725 PHILIP COX RICHARDSON & TAYLOR PHILIP COX and DON HARRINGTON 1972 Akuna Bay Marina Liberator General San Martin Drive, Ku-ring-gai Akuna Bay Warringah -

Issues Paper for the Grey Nurse Shark (Carcharias Taurus)

Issues Paper for the Grey Nurse Shark (Carcharias taurus) 2014 The recovery plan linked to this issues paper is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/resource/recovery-plan-grey-nurse-shark-carcharias-taurus © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to Department of the Environment, Public Affairs, GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 or email [email protected]. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Cover images by Justin Gilligan Photography Contents List of figures ii List of tables ii Abbreviations ii 1 Summary 1 2 Introduction 2 2.1 Purpose 2 2.2 Objectives 2 2.3 Scope 3 2.4 Sources of information 3 2.5 Recovery planning process 3 3 Biology and ecology 4 3.1 Species description 4 3.2 Life history 4 3.3 Diet 5 3.4 Distribution 5 3.5 Aggregation sites 8 3.6 Localised movements at aggregation sites 10 3.7 Migratory movements -

Albany Coast Draft Management Plan 2016

Albany coast draft management plan 2016 Albany coast draft management plan 2016 Conservation Commission of Western Australia Department of Parks and Wildlife Department of Parks and Wildlife 17 Dick Perry Avenue KENSINGTON WA 6151 Phone: (08) 9219 9000 Fax: (08) 9334 0498 www.dpaw.wa.gov.au © State of Western Australia 2016 May 2016 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Department of Parks and Wildlife. ISBN 978-1-921703-67-6 (print) ISBN 978-1-921703-68-3 (online) This management plan was prepared by the Conservation Commission of Western Australia through the agency of the Department of Parks and Wildlife. Questions regarding this management plan should be directed to: Planning Branch Department of Parks and Wildlife Locked Bag 104 Bentley Delivery Centre WA 6983 Phone: (08) 9219 9000 The recommended reference for this publication is: Department of Parks and Wildlife (2016) Albany coast draft management plan 2016. Department of Parks and Wildlife, Perth. This document is available in alternative formats on request. Please note: URLs in this document which conclude a sentence are followed by a full point. If copying the URL please do not include the full point. Front cover photos Main The new recreation facilities at The Gap in Torndirrup National Park. Photo – Parks and Wildlife Top left Gilbert’s potoroo or ngilgyte (Potorous gilberti). -

Reconstructing Aboriginal Economy and Society: the New South Wales

Reconstructing Aboriginal 12 Economy and Society: The New South Wales South Coast at the Threshold of Colonisation John M. White Ian Keen’s 2004 monograph, Aboriginal Economy and Society: Australia at the Threshold of Colonisation, represents the first anthropological study to draw together comparative pre- and postcolonial data sets and sources to explain the nature and variety of Aboriginal economy and society across the Australian continent. Keen’s (2004: 5) rationalisation for comparing the economy and society of seven regions was ‘mainly descriptive and analytical’, in order to ‘shed light on the character of each region, and to bring out their similarities and differences’. In doing so, as Veth (2006: 68) commented in his review of the book, ‘It speaks to meticulous and exhaustive research from myriad sources including social anthropology, linguistics, history, ecology and, not the least, archaeology’. Following its publication, Aboriginal Economy and Society: Australia at the Threshold of Colonisation won Keen his second Stanner Award from the Council of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies in 2005. In this chapter, I draw upon Keen’s comparative method to profile the ecology, institutions and economy of the Yuin people of (what is now) the Eurobodalla region of the New South Wales south coast at the time of European colonisation.1 1 Elsewhere I have documented the role of Aboriginal workers in the New South Wales south coast horticultural sector in the mid-twentieth century (White 2010a, 2010b, 2011) and have detailed the reactions of Yuin people to colonial incursions, which involved the development of intercultural relations that were mediated by exchange (White 2012). -

Beaches of the New South Wales Coast

BEACHES OF THE NEW SOUTH WALES COAST A guide to their nature, characteristics, surf and safety ANDREW D SHORT Coastal Studies Unit School of Geosciences F09 University of Sydney Sydney, NSW 2006 COPYRIGHT © AUSTRALIAN BEACH SAFETY AND MANAGEMENT PROGRAM Coastal Studies Unit and Surf Life Saving Australia Ltd School of Geosciences F09 1 Notts Ave University of Sydney Locked Bag 2 Sydney NSW 2006 Bondi Beach NSW 2026 Short, Andrew D Beaches of the New South Wales Coast (2nd edition) 1-920898-15-8 Published February 2007 Other books in this series by A D Short: • Beaches of the New South Wales Coast, 1993 (1st edition) 0-646-15055-3 • Beaches of the Victorian Coast and Port Phillip Bay, 1996 0-9586504-0-3 • Beaches of the Queensland Coast: Cooktown to Coolangatta, 2000 0-9586504-1-1 • Beaches of the South Australian Coast and Kangaroo Island, 2001 0-9586504-2-X • Beaches of the Western Australian Coast: Eucla to Roebuck Bay, 2005 0-9586504-3-8 • Beaches of the Tasmania Coast and Islands, 2006 1-920898-12-3 • Beaches of the Northern Australian Coast: The Kimberley, Northern Territory and Cape York, 2006 1-920898-16-6 Published by: Sydney University Press University of Sydney www.sup.usyd.edu.au Printed by: University Publishing Service University of Sydney Copies of all books in this series may be purchased online from Sydney University Press at: http://www.sup.usyd.edu.au/marine New South Wales beach database: Inquiries about the New South Wales beach database should be directed to Surf Life Saving Australia at [email protected] Cover photograph: Boomerang Beach (NSW 208) is an exposed rip dominated beach, with six well developed beach rips visible in this view. -

Annual & Sustainability Report

ANNUAL & SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2009-10 Contents Letter from the President 4 Part 1: ACF’s Sustainability Scorecard 6 Part 2: Our Environmental and Social impact 6 Our sustainable practices 7 Our own wellbeing 7 Reaching out 9 Part 3: Our Campaigns 9 The Climate Project – Australia 9 The protection of Koongarra 9 Sustainable Cities Index 10 Just Add Water 10 Healthy oceans 10 Alwal National Park 11 Other campaigns: from red gums to green homes 12 Part 4: Our Supporters 17 Part 5: Financials 17 ACF board 23 Independent auditor’s report 25 Financials Dear ACF Supporter commit to keep warming to below two degrees. As we look back and refl ect on the year I was also impressed and proud when passed, the challenges met and the lessons 10 of our Climate Project presenters learned, I am reminded again of the joined with colleagues from the Union strength, resilience and commitment of Climate Connectors and the Australian ACF supporters. Youth Climate Coalition in Canberra. Never was this more evident to me They met with 56 MPs to tell them that than during the diffi cult Copenhagen millions of Australians care deeply about campaign, in which ACF supporters joined climate change and climate policies would together to lobby world leaders at the infl uence their votes in the federal election. UN Climate Conference. In the lead up, There are many ways supporters, like ACF campaigners worked hard to deliver you, contribute to ACF’s work protecting science-based policy to then Prime Minister Australia’s unique natural heritage. The Kevin Rudd and senior offi cials attending number of people regularly participating in the talks.