University Microfilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rawsthorne and Other Rarities

Rawsthorne and other rarities Alan Rawsthorne (1905-1971) Chamber Cantata 11:59 1 I Of a Rose is al myn Song 3:34 2 II Lenten ys come 2:17 3 III Wynter Wakeneth al my Care 4:11 4 IV The Nicht is near gone 1:56 Clare Wilkinson (mezzo-soprano), Harvey Davies (harpsichord), Solem Quartet Halsey Stevens (1908-1989) Sonatina Piacevole 5:29 5 I Allegro moderato 1:52 6 II Poco lento, quasi ciaccona 1:50 7 III Allegro 1:47 John Turner (recorder), Harvey Davies (harpsichord) Alan Rawsthorne (1905-1971), edited and arranged by Peter Dickinson (b.1934) Practical Cats (texts by T.S. Eliot) 21:09 8 I Overture 2:22 9 II The Naming of Cats 2:59 10 III The Old Gumbie Cat 4:25 11 IV Gus, the Theatre Cat 3:48 12 V Bustopher Jones 2:32 13 VI Old Deuteronomy 3:37 14 VII The Song of the Jellicles 1:24 Mark Rowlinson (reciter), Peter Lawson (piano) Basil Deane (1928-2006) / Raymond Warren (b.1928) The Rose Tree (texts by W. B. Yeats) 5:27 15 I The Rose Tree 2:23 16 II I am of Ireland 3:04 Clare Wilkinson (mezzo-soprano), John Turner (recorder), Stephanie Tress (cello) S This recording is dedicated to the memory of John McCabe, CBE Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) 17 The Willow Whistle 1:04 Clare Wilkinson (mezzo-soprano), John Turner (bamboo pipe) Karel Janovický (b.1930) 18 The Little Linden Pipe 3:19 John Turner (recorder) Alan Rawsthorne (1905-1971) String Quartet in B minor 15:12 19 I Fugue (molto adagio) — 5:00 20 II Andante – Allegretto 3:40 21 III Molto allegro quasi presto 6:31 Solem Quartet Donald Waxman (b.1925) 22 Serenade and Caprice 7:33 John -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Final January 2019 Newsletter 1-2-19

January 2019 Talking Pointes Jane Sheridan, Editor 508.367.4949 [email protected] From the Desk of the President Showcase Luncheon Richard March 941.343.7117 “Our Dancers—The Boys From [email protected] Brazil” Monday, February 11, 2019, Bird I’m excited for you to read about our winter party – Key Yacht Club, 11:30 AM Carnival at Mardi Gras – elsewhere in this newsletter. It will be at the Hyatt Boathouse on Carnival at Mardi Gras February 25th. This is a chance to have fun with other Monday, February 25, 2019, The Boathouse at the Hyatt Regency, Friends and dancers from the Company. It is also an 5:30 PM - 7:30 PM opportunity to help us raise funds for the Ballet. We need help in preparing a number of themed “Spring Fling” baskets that will be auctioned at the event. In the past, Sunday, March 31, 2019, The we’ve had French, Italian, wine, and chocolate Sarasota Garden Club, 4:00 PM – baskets, among others. Those who prepare baskets are 6:30 PM asked to spend no more than $50 in preparing them. However, you can add an unlimited number of gift Showcase Luncheon certificates or donations that will increase the appeal. Margaret Barbieri, Assistant Director, The Sarasota Ballet, If you would like to pitch in to support this effort, "Giselle: Setting An Iconic Work” please contact Phyllis Myers for information at Monday, April 15, 2019, Michael’s [email protected]. And, please come to On East, 11:30 AM the party. I am certain you will have fun! Were you able to see the performance of our dancers Pointe of Fact from the Studio Company and the Margaret Barbieri November was a record-setting Conservatory at the Opera House? Together with the month for the Friends of The Key Chorale, they took part in a program called Sarasota Ballet. -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

Wild Worship of a Lost and Buried Past”: Enchanted Bofulletin the History of Archaeology Archaeologies and the Cult of Kata, 1908–1924

Wickstead, H 2017 “Wild Worship of a Lost and Buried Past”: Enchanted Bofulletin the History of Archaeology Archaeologies and the Cult of Kata, 1908–1924. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 27(1): 4, pp. 1–18, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/bha-596 RESEARCH PAPER “Wild Worship of a Lost and Buried Past”: Enchanted Archaeologies and the Cult of Kata, 1908–1924 Helen Wickstead Histories of archaeology traditionally traced the progress of the modern discipline as the triumph of secular disenchanted science over pre-modern, enchanted, world-views. In this article I complicate and qualify the themes of disenchantment and enchantment in archaeological histories, presenting an analysis of how both contributed to the development of scientific theory and method in the earliest decades of the twentieth century. I examine the interlinked biographies of a group who created a joke religion called “The Cult of Kata”. The self-described “Kataric Circle” included notable archaeologists Harold Peake, O.G.S. Crawford and Richard Lowe Thompson, alongside classicists, musicians, writers and performing artists. The cult highlights the connections between archaeology, theories of performance and the performing arts – in particular theatre, music, folk dance and song. “Wild worship” was linked to the consolidation of collectivities facilitating a wide variety of scientific and artistic projects whose objectives were all connected to dreams of a future utopia. The cult parodied archaeological ideas and methodologies, but also supported and expanded the development of field survey, mapping and the interpretation of archaeological distribution maps. The history of the Cult of Kata shows how taking account of the unorthodox and the interdisciplinary, the humorous and the recreational, is important within generously framed approaches to histories of the archaeological imagination. -

Men's Glee Repertoire (2002-2021)

MEN'S GLEE REPERTOIRE (2002-2021) Ain-a That Good News - William Dawson All Ye Saints Be Joyful - Katherine Davis Alleluia - Ralph Manuel Ave Maria - Franz Biebl Ave Maria - Jacob Arcadet Ave Maria - Joan Szymko Ave Maris Stella - arr. Dianne Loomer Beati Mortui - Fexlix Mendelssohn Behold the Lord High Executioner (from The Mikado )- Gilbert and Sullivan Blades of Grass and Pure White Stones -Orin Hatch, Lowell Alexander, Phil Nash/ arr. Keith Christopher Blagoslovi, dushé moyá Ghospoda - Mikhail Mikhailovich Ippolitov-Ivanov Blow Ye Trumpet - Kirke Mechem Bright Morning Stars - Shawn Kirchner Briviba – Ēriks Ešenvalds Brothers Sing On - arr. Howard McKinney Brothers Sing On - Edward Grieg Caledonian Air - arr. James Mullholland Come Sing to Me of Heaven - arr. Aaron McDermid Cornerstone – Shawn Kirchner Coronation Scene (from Boris Goudonov ) - Modest Petrovich Moussorgsky Creator Alme Siderum - Richard Burchard Daemon Irrepit Callidu- György Orbain Der Herr Segne Euch (from Wedding Cantata ) - J. S. Bach Dereva ni Mungu – Jake Runestad Dies Irae - Z. Randall Stroope Dies Irae - Ryan Main Do You Hear the Wind? - Leland B. Sateren Do You Hear What I Hear? - arr. Harry Simeone Down in the Valley - George Mead Duh Tvoy blagi - Pavel Chesnokov Entrance and March of the Peers (from Iolanthe)- Gilbert and Sullivan Five Hebrew Love Songs - Eric Whitacre For Unto Us a Child Is Born (from Messiah) - George Frideric Handel Gaudete - Michael Endlehart Git on Boa'd - arr. Damon H. Dandridge Glory Manger - arr. Jon Washburn Go Down Moses - arr. Moses Hogan God Who Gave Us Life (from Testament of Freedom) - Randall Thompson Hakuna Mungu - Kenyan Folk Song- arr. William McKee Hark! I Hear the Harp Eternal - Craig Carnahan He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands - arr. -

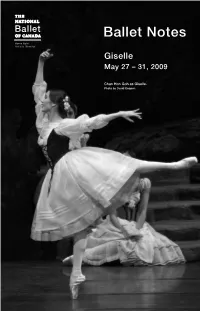

Ballet Notes Giselle

Ballet Notes Giselle May 27 – 31, 2009 Chan Hon Goh as Giselle. Photo by David Cooper. 2008/09 Orchestra Violins Clarinets • Fujiko Imajishi, • Max Christie, Principal Souvenir Book Concertmaster Emily Marlow, Lynn Kuo, Acting Principal Acting Concertmaster Gary Kidd, Bass Clarinet On Sale Now in the Lobby Dominique Laplante, Bassoons Principal Second Violin Stephen Mosher, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., Founder James Aylesworth, Jerry Robinson Featuring beautiful new images Acting Assistant Elizabeth Gowen, George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Concertmaster by Canadian photographer Contra Bassoon Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Jennie Baccante Sian Richards Artistic Director Executive Director Sheldon Grabke Horns Xiao Grabke Gary Pattison, Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Nancy Kershaw Vincent Barbee Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-Leheniuk Derek Conrod Principal Conductor • Csaba Koczó • Scott Wevers Yakov Lerner Trumpets Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Jayne Maddison Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Richard Sandals, Principal Ron Mah YOU dance / Ballet Master Mark Dharmaratnam Aya Miyagawa Raymond Tizzard Aleksandar Antonijevic, Guillaume Côté, Wendy Rogers Chan Hon Goh, Greta Hodgkinson, Filip Tomov Trombones Nehemiah Kish, Zdenek Konvalina, Joanna Zabrowarna David Archer, Principal Heather Ogden, Sonia Rodriguez, Paul Zevenhuizen Robert Ferguson David Pell, Piotr Stanczyk, Xiao Nan Yu Violas Bass Trombone Angela Rudden, Principal Victoria Bertram, Kevin D. Bowles, Theresa Rudolph Koczó, Tuba -

Numerical Listing

SEQ DISC NO LABEL CDN PRICE PERFORMER DESCRIPTION a a THREE FOR TWO! ON ALL ITEMS PRICED AT £5.00, ONE- THIRD (1/3) OFF ALL ORDERS FOR 3 OR MORE a a 23776 0 10 1441-3 Supraphon, blue m A1 £10.00 Talich, Vaclav Vol. 1. Suk: Serenade for Strings; Asrael; Ripening. Czech PO c 22047 1 11 1106 Supraphon s A1 £5.00 Vlach SQ Beethoven: Quartets, Opp.18-1; 18-6 bb 22524 1 11 1755 Supraphon s A1 £5.00 Prague SQ Lubomir Zelezny: Clt. Quintet; Wind Quintet; Piano Trio. Prague Wind Quintet, Smetana Trio bb 23786 10 Penzance, USA m A1 £8.00 Callas, Maria, s Wagner: Parsifal, Act 2. Baldelli, Modesti, Pagliughi, -Gui. Live, 20.xi.50. In Italian a 22789 1007831 VdsM, References m A1 £7.00 Kreisler, Fritz, vn Beethoven; Sonatas 5, "Spring"; 9, "Kreutzer". F. Rupp, pf bb 23610 101 Rara Avis, lacquer m A-1- £10.00 Ginsburg, Grigory, pf Liszt: Bells of Geneva, Campanella, Rigoletto, Spanish Rhapsody / Weber: Rondo brillante / Chopin: Etudes, Op.25, 1-3. From 78s, semi-private issue b 22800 12T 160 Topic m A1 £7.00 Folk Songs of Britain, 1 Child Ballads 1. Various artists (field recordings) e 22707 13029 AP DGG, Archiv, Ger., m A1 £40.00 Schneiderhan, Wolfgang, vn Bach: Partita 2, D minor, for solo violin. Sleeve: buff, gatefold 10" bb 22928 133 004 SLPE DGG, Ger., tulip, 10" s A1 £12.00 Bolechowska, Alina, s Chopin: Lieder. S. Nadgrizowski, pf a 22724 133 122 SLP DGG, Ger., red, tulip, s A1 £12.00 Markevitch, Igor, dir Mozart: Coronation Mass. -

Tfw H O W a N D W H Y U/Orvcfoiboo&O£ • ^Jwhy Wonder W*

Tfw HOW AND • WHY U/orvcfoiBoo&o£ ^JWhy Wonder W* THE HOW AND WHY WONDER BOOK OF B> r Written by LEE WYNDHAM Illustrated by RAFAELLO BUSONI Editorial Production: DONALD D. WOLF Edited under the supervision of Dr. Paul E. Blackwood Washington, D. C. \ Text and illustrations approved by Oakes A. White Brooklyn Children's Museum Brooklyn, New York WONDER BOOKS • NEW YORK Introduction The world had known many forms of the dance when ballet was introduced. But this was a new kind of dance that told a story in movement and pantomime, and over the years, it has become a very highly developed and exciting art form. The more you know about ballet, the more you can enjoy it. It helps to know how finished ballet productions depend on the cooperative efforts of many people — producers, musicians, choreographers, ballet masters, scene designers — in addition to the dancers. It helps to know that ballet is based on a few basic steps and movements with many possible variations. And it helps to know that great individual effort is required to become a successful dancer. Yet one sees that in ballet, too, success has its deep and personal satisfactions. In ballet, the teacher is very important. New ideas and improvements have been introduced by many great ballet teachers. And as you will read here, "A great teacher is like a candle from which many other candles can be lit — so many, in fact, that the whole world can be made brighter." The How and Why Wonder Book of Ballet is itself a teacher, and it will make the world brighter because it throws light on an exciting art form which, year by year, is becoming a more intimate and accepted part of the American scene. -

Diaghilev and London

Diaghilev and London, A Talk by Graham Bennett, Crouch End and District U3A member We are not exactly the best of friends with Russia these days - But just over a century ago, Russia exported something that actually transformed the cultural life of London. This talk is about a quite extraordinary Russian Impresario and two equally extraordinary women who were part of his project The project was a Russian Dance Company that created a revolution in the world of dance, and London was to play a big part in its success. This company is the Ballet Russes. The impresario is Serge Diaghilev, born in 1872 in Perm in deepest Russia, who would create the Ballet Russes. Lydia Lopokova from St Petersburg, born in 1892, one of Diaghilev's star ballerinas. And last but not least, our very own Hilda Munnings from Wanstead in East London, born in 1896. Also to become a vitally important member of the company The story starts in St Petersburg in 1901, the heart of the Russian Empire, at the famous Mariinsky Theatre. Their choreographer Marius Petipa and composer Tchaikovsky had already created masterpieces such as The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker and Swan Lake. These are such familiar names to us today but they were virtually unknown outside Russia at that time. Over in England we were still having a jolly knees up and sing-along at the Music Hall and even in France, ballet had degenerated to a pale shadow of its former glory. In 1901, Lydia Lopokova, just 9 years old, auditioned for a place at the prestigious Imperial Theatre School in St Petersburg. -

WRAP Thesis Ruben 1998.Pdf

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/59558 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. 1 GRACE UNDER PRESSURE: RE-READING GISELLE. Mel Ruben Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature University of Warwick Department of English and Comparative Literary Studies September, 1998 2 For Peter, Alice, Audrey and Theda Ruben 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 6 Summary 7 Terminology 8 Preface 1. Introduction 9 2. My Personal Aims for this Thesis 11 3. My Own Mythology 16 4. Ballet Writing and Ballet Going in the 1990s 20 5. The Shape of Love 35 Notes to the Preface 38 ChaQter One: The Ballet Called Giselle 1. Jntroductton 42 2. Giselle: a Romantic Ballet 42 3. The Plot of Giselle 51 4~The First Giselle 60 5. Twentieth Century Giselles 64 6. The Birmingham Royal Ballet's 1992 Giselle 74 7. Locating Ballet in Dance Studies 86 8. Using Ballet as a Text 91 9. Methodology 98 Notes to Chapter One 107 ChaQter Two Plot: Blade Runner and Giselle 1. Introduction 111 2. The Two Blade Runners 113 3. The Plot of Blade Runner 117 4. Matching the Myths 129 5. Endings and Closures 159 6.