WRAP Thesis Ruben 1998.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio 3 Listings for 10 – 16 January 2015 Page

Radio 3 Listings for 10 – 16 January 2015 Page 1 of 10 SATURDAY 10 JANUARY 2015 5:01 AM SAT 14:00 Saturday Classics (b04xrnhb) Brahms, Johannes (1833-1897) Simon Heffer: Best of British Playlist SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b04wmy50) Academic Festival Overture, Op.80 Casals Quartet BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Grant Llewellyn Episode 2 (Conductor) The Casals Quartet play Mozart, Ligeti and Brahms. Presented Inspired by Radio 3 Breakfast's "Best of British" playlist which by Jonathan Swain. 5:12 AM ran throughout 2014, journalist Simon Heffer continues the Vivaldi, Antonio (1678-1741) choice of his favourite music by British composers, including 1:01 AM Concerto in D minor for strings and basso continuo (RV.128) works by Frank Bridge, Gerald Finzi, Herbert Howells, Eric Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus (1756-1791) Arte dei Suonatori, Eduardo Lopez (conductor) Coates and George Lloyd. String Quartet in C major (K.465) "Dissonance" Casals Quartet: Vera Martínez-Mehner and Abel Tomàs 5:18 AM (violins), Jonathan Brown (viola), Arnau Tomàs (cello) Strauss, Richard (1864-1949) SAT 16:00 Sound of Cinema (b04xrnhd) Der Abend (Op.34 No.1) for 16 part choir Film Musicals - The Last 50 Years 1:29 AM Danish National Radio Choir, Stefan Parkman (conductor) Ligeti, Gyorgy (1923-2009) The Sound of Music with Julie Andrews is 50 years old - in the Quartet no. 1 (Metamorphoses nocturnes) for strings 5:27 AM week of the release of Sondheim's screen version of Into The Casals Quartet Chopin, Fryderyk [1810-1849] Woods, Matthew Sweet looks back on the last half century of Krakowiak - rondo for piano and orchestra (Op.14) in F major the screen musical. -

UNITEL PROUDLY REPRESENTS the INTERNATIONAL TV DISTRIBUTION of Browse Through the Complete Unitel Catalogue of More Than 2,000 Titles At

UNITEL PROUDLY REPRESENTS THE INTERNATIONAL TV DISTRIBUTION OF Browse through the complete Unitel catalogue of more than 2,000 titles at www.unitel.de Date: March 2018 FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CONTENT BRITTEN: GLORIANA Susan Bullock/Toby Spence/Kate Royal/Peter Coleman-Wright Conducted by: Paul Daniel OPERAS 3 Staged by: Richard Jones BALLETS 8 Cat. No. A02050015 | Length: 164' | Year: 2016 DONIZETTI: LA FILLE DU RÉGIMENT Natalie Dessay/Juan Diego Flórez/Felicity Palmer Conducted by: Bruno Campanella Staged by: Laurent Pelly Cat. No. A02050065 | Length: 131' | Year: 2016 OPERAS BELLINI: NORMA Sonya Yoncheva/Joseph Calleja/Sonia Ganassi/ Brindley Sherratt/La Fura dels Baus Conducted by: Antonio Pappano Staged by: Àlex Ollé Cat. -

Film Guide April 2018

FILM GUIDE APRIL 2018 www.loftcinema.org BEST F(R)IENDS & THE DISASTER ARTIST W/ GREG SESTERO IN PERSON! LAWRENCE OF ARABIA PRESENTED IN 70MM • SUNDAY, APRIL 15 AT NOON! ENJOY BEER & WINE AT THE LOFT CINEMA! We also offer Fresco Pizza*, Tucson Tamale Factory Tamales, Burritos from Tumerico, Ethiopian Wraps from Cafe Desta and Sandwiches from the 4th Ave. Deli, along with organic popcorn, craft chocolate bars, vegan cookies and more! *Pizza served after 5pm daily. APRIL 2018 SPECIAL ENGAGEMENTS 4-23 JOURNALISM ON SCREEN 6 BEER OF THE MONTH: LOFT MEMBERSHIPS 8 FIRESTONE LAGER LOFT JR. 12 BY FIRESTONE WALKER BREWING CO. ESSENTIAL CINEMA 14 ONLY $3.50 ALL THROUGH APRIL! SCIENCE ON SCREEN 16 NATIONAL THEATRE LIVE 17 NEW AT THE LOFT CINEMA! MONTH-LONG SERIES 19-20 The Loft Cinema now offers Closed Captions and Audio LOFT STAFF SELECTS 21 Descriptions for films whenever they are available. Check our COMMUNITY RENTALS 23-24 website to see which films offer this technology. NEW FILMS 25-34 REEL READS SELECTION 32 FILM GUIDES ARE AVAILABLE AT: MONDO MONDAYS 35 • aLoft Hotel • Espresso Art • Revolutionary Grounds • Antigone Books • Fantasy Comics • Rincon Market CULT CLASSICS 36 • Aqua Vita • First American Title • Rocco’s Little Chicago • Art Institute of Tucson • Fresco Pizza • Rogue Theatre THE LOFT CINEMA • AZ Title Security • Fronimos • Santa Barbara Ice Cream 3233 E. Speedway Blvd. • Bentley’s • Heroes & Villains • Shot in the Dark Café Tucson, AZ 85716 • Black Crown Coffee • Hotel Congress • Southern AZ AIDS • Bookman’s • How Sweet It Was -

A Mixed Blessing at the Ballet 01

Daily Telegraph July 28 2001 A mixed blessing at the ballet Photo Sheila Rock As Anthony Dowell leaves the Royal Ballet, dance critic Ismene Brown assesses his 15-year regime as director - and stars pay tribute below AT THE Royal Ballet the countdown has begun to the end of an era. A week tonight, amid flowers, Champagne and tears, Sir Anthony Dowell, the longest-serving ballet director since the company’s founder, Ninette de Valois, will end his 15-year regime. He was undoubtedly one of the great world stars of dancing, and the “Celebration Programme” will mark his achievements as such. But about his success as director of the company, opinion is far from unanimous. What makes a good director? The question has never been more of a poser than during Dowell\s captaincy of the ballet, in the most turbulent years of the Royal Opera House’s history. There are many pluses on Dowell’s account sheet - his maintenance of high classical technical standards, his welcoming of key foreign artists into the Royal (particularly Sylvie Guillem and Irek Mukhamedov), his inspiring coaching, to which leading guest stars attest opposite. The rise of Darcey Bussell to world acclaim, the forging of a superb partnership between Mukhamedov and Viviana Durante, this final, nostalgic and beautiful 2000-01 season - these are positive memories. He will be noted as a conservative, and many welcomed this after an insecure period of modernising under his predecessor, Norman Morrice. Whether conservatism has served the company well for the future, though, is debatable. In the shifting landscape of ballet, conservatism is not enough to hold steady. -

Leanne Benjamin Built for Ballet

October 2021 M October 2021 Melbourne Books LEANNE BENJAMIN An Autobiography BUILT FOR BALLET LEANNE BENJAMIN WITH SARAH CROMPTON This autobiography by Leanne Benjamin with Sarah Crompton reveals the extraordinary life and career of one of the world’s most important ballet dancers of the past 50 years. Leanne was born and raised in the central Queensland town of Rockhampton in a tightly knit hard-working Catholic family. At the age of 3 she attended her first ballet class and at 16 she was accepted into the Royal Ballet School in London and at 18 danced her first leading role on the Royal Opera House stage in the school’s performance of Giselle that catapulted her to a stellar career. The book takes you behind the scenes to find a real understanding of the pleasure and the pain, the demands and the intense commitment it requires to become a ballet dancer. It’s a book for ballet-lovers which will explain from Benjamin’s personal point of view, how ballet has changed and is changing. It’s a book of history: she was first taught by the people who created ballet in its modern form and now she works with the dancers of today, handing on all she has known and learnt. But it’s also a book for people who are just interested in the psychology of achievement, how you go from being a child in small town Rockhampton in the centre of Australia to being a power on the world’s biggest stages — and how an individual copes with the ups and downs of that kind of career. -

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, a MATTER of LIFE and DEATH/ STAIRWAY to HEAVEN (1946, 104 Min)

December 8 (XXXI:15) Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH/ STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN (1946, 104 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger Music by Allan Gray Cinematography by Jack Cardiff Film Edited by Reginald Mills Camera Operator...Geoffrey Unsworth David Niven…Peter Carter Kim Hunter…June Robert Coote…Bob Kathleen Byron…An Angel Richard Attenborough…An English Pilot Bonar Colleano…An American Pilot Joan Maude…Chief Recorder Marius Goring…Conductor 71 Roger Livesey…Doctor Reeves Robert Atkins…The Vicar Bob Roberts…Dr. Gaertler Hour of Glory (1949), The Red Shoes (1948), Black Narcissus Edwin Max…Dr. Mc.Ewen (1947), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), 'I Know Where I'm Betty Potter…Mrs. Tucker Going!' (1945), A Canterbury Tale (1944), The Life and Death of Abraham Sofaer…The Judge Colonel Blimp (1943), One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), 49th Raymond Massey…Abraham Farlan Parallel (1941), The Thief of Bagdad (1940), Blackout (1940), The Robert Arden…GI Playing Bottom Lion Has Wings (1939), The Edge of the World (1937), Someday Robert Beatty…US Crewman (1935), Something Always Happens (1934), C.O.D. (1932), Hotel Tommy Duggan…Patrick Aloyusius Mahoney Splendide (1932) and My Friend the King (1932). Erik…Spaniel John Longden…Narrator of introduction Emeric Pressburger (b. December 5, 1902 in Miskolc, Austria- Hungary [now Hungary] —d. February 5, 1988, age 85, in Michael Powell (b. September 30, 1905 in Kent, England—d. Saxstead, Suffolk, England) won the 1943 Oscar for Best Writing, February 19, 1990, age 84, in Gloucestershire, England) was Original Story for 49th Parallel (1941) and was nominated the nominated with Emeric Pressburger for an Oscar in 1943 for Best same year for the Best Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Writing, Original Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Missing Missing (1942) which he shared with Michael Powell and 49th (1942). -

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years Ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 Pages This PDF History Timeline Has Been Extracted

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 pages This PDF History Timeline has been extracted from the History World web site's time line. The PDF is a very simplified version of the History World timeline. The PDF is stripped of all the links found on that timeline. If an entry attracts your interest and you want further detail, click on the link at the foot of each of the PDF pages and query the subject or the PDF entry on the web site, or simply do an internet search. When I saw the History World timeline I wanted a copy of it for myself and my family in a form that we could access off-line, on demand, on the device of our choice. This PDF is the result. What attracted me particularly about the History World timeline is that each event, which might be earth shattering in itself with a wealth of detail sufficient to write volumes on, and indeed many such events have had volumes written on them, is presented as a sort of pared down news head-line. Basic unadorned fact. Also, the History World timeline is multi-faceted. Most historic works focus on their own area of interest and ignore seemingly unrelated events, but this timeline offers glimpses of cross-sections of history for any given time, embracing art, politics, war, nations, religions, cultures and science, just to mention a few elements covered. The view is fascinating. Then there is always the question of what should be included and what excluded. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Arthur Mitchell

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Arthur Mitchell Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Mitchell, Arthur, 1934-2018 Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Arthur Mitchell, Dates: October 5, 2016 Bulk Dates: 2016 Physical 9 uncompressed MOV digital video files (4:21:20). Description: Abstract: Dancer, choreographer, and artistic director Arthur Mitchell (1934 - 2018 ) was a principal dancer for the New York City Ballet for fifteen years. In 1969, he co-founded the Dance Theatre of Harlem, the first African American classical ballet company and school. Mitchell was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on October 5, 2016, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2016_034 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Dancer, choreographer and artistic director Arthur Mitchell was born on March 27, 1934 in Harlem, New York to Arthur Mitchell, Sr. and Willie Hearns Mitchell. He attended the High School of Performing Arts in Manhattan. In addition to academics, Mitchell was a member of the New Dance Group, the Choreographers Workshop, Donald McKayle and Company, and High School of Performing Arts’ Repertory Dance Company. After graduating from high school in 1952, Mitchell received scholarships to attend the Dunham School and the School of American received scholarships to attend the Dunham School and the School of American Ballet. In 1954, Mitchell danced on Broadway in House of Flowers with Geoffrey Holder, Louis Johnson, Donald McKayle, Alvin Ailey and Pearl Bailey. -

2.Documentals, Pel.Lícules, Concerts, Ballet, Teatre

2.DOCUMENTALS, PEL.LÍCULES, CONCERTS, BALLET, TEATRE..... L’aparició del format DVD ha empès a que molts teatres, televisions, productores, etc hagin decidit reeeditar programes que havien contribuït a popularitzar i divulgar diferents aspectes culturals. També permet elaborar documents que en altres formats son prohibitius, per això avui en dia, hi ha molt a on triar. En aquest arxiu trobareu: -- Documentals a) dedicats a Wagner o la seva obra b) dedicats a altres músics, obres, cantants, directors, ... -- Grabacions de concerts i recitals a) D’ obres wagnerianes b) D’ altres obres i compositors -- Pel.lícules que ens acosten al món de la música -- Ballet clàssic -- Teatre clàssic Associació Wagneriana. Apartat postal 1159 Barcelona Http://www. associaciowagneriana.com. [email protected] DOCUMENTALS A) DEDICATS A WAGNER O LA SEVA OBRA 1. “The Golden Ring” DVD: DECCA Film de la BBC que mostre com es va grabar en disc La Tetralogia en 1965, dirigida per Georg Solti. El DVD es centre en la grabació del Götterdämmerung. Molt recomenable 2. Sing Faster. The Stagehands’Ring Cycle. DVD: Docurama Filmat per John Else presenta com es va preparar el montatge de la Tetralogia a San Francisco. Interesant ja que mostra la feina que cal realitzar en diferents àmbits per organitzar un Anell, però malhauradament la producció escenogrficament és bastant dolenta. 3. “Parsifal” DVD: Kultur. Del director Tony Palmer, el que va firmar la biografia deplorable del compositor Wagner, aquest documental ens apropa i allunya del Parsifal de Wagner. Ens apropa en les explicacions de Domingo i ens allunya amb les bestieses de Gutman. Prescindible. B) DEDICATS A ALTRES MÚSICS, OBRES, CANTANTS, DIRECTORS, .. -

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première Catalogue 2018 Lists UNITEL’S New Productions of 2017 CATALOGUE 2018 Plus New Additions to the Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première catalogue 2018 lists UNITEL’s new productions of 2017 CATALOGUE 2018 plus new additions to the catalogue. For a complete list of more than 2.000 UNITEL productions and the Avant Première catalogues of 2015–2017 please visit www.unitel.de FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany WORLD SALES CEO: Jan Mojto C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Editorial team: Franziska Pascher, Dr. Martina Kliem, Arthur Intelmann Layout: Manuel Messner/luebbeke.com Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager All information is not contractual and subject to change without prior notice. [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. [email protected] Date of Print: February 2018 © UNITEL 2018 All rights reserved Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director Front cover: Alicia Amatriain & Friedemann Vogel in John Cranko’s “Onegin” / Photo: Stuttgart Ballet [email protected] [email protected] ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 100TH BIRTHDAY UNITEL CELEBRATES AVAILABLE FOR THE FIRST TIME FOR GLOBAL DISTRIBUTION LEONARD BERNSTEIN 1918 – 1990 Leonard Bernstein, a long-time exclusive artist of Unitel, was America’s ambassador to the world of music. -

Tamara Rojo Artistic Director of the English National Ballet Tamara Began Dancing in Madrid at the Víctor Ullate School, Where

Tamara Rojo Artistic Director of the English National Ballet Tamara began dancing in Madrid at the Víctor Ullate School, where she took part in an extensive repertoire of classical roles. She won a Gold Medal at the Paris International Dance Competition and the Special Jury Prize unanimously. Galina Samsova asked her to join the Scottish Ballet and she later received a personal invitation from Derek Deane to join the English National Ballet, where she became director after six months. She danced the whole range of leading roles with the company, including Juliet (Romeo and Juliet) and Clara (The Nutcracker), which Derek Deane created expressly for her. Tamara joined The Royal Ballet as Principal Dancer at the invitation of Sir Anthony Dowell. She is also a regular guest of the Mariinsky Ballet, La Scala Ballet, Tokyo Ballet, New National Theatre, Tokyo, the Cuban National Ballet, the National Ballet of China, the Lithuanian National Ballet, the Mikhailovsky Ballet, the Royal Swedish Ballet and the Finnish National Ballet. She has also performed at the prestigious World Ballet Festival in Tokyo and at galas all over the world. In 2010 she was recognised for her artistic excellence with the Laurence Olivier Award for the Best New Dance Production with Goldberg: the Brandstrup - Rojo Project. She has been awarded the Prince of Asturias Prize, the Gold Medal for Fine Arts and the Encomienda de Numero de Isabel la Catolica. Other recognitions include the Prix Benois de la Danse, The Times Dancer Revelation of the Year, the National Dance Critics Award, the Barclay’s Award for Outstanding Achievement in Dance, the Positano Dance Award, Léonide Massine Premi al Valore, the Italian Critics Award, the International Arts Medal and the Madrid Performance Award. -

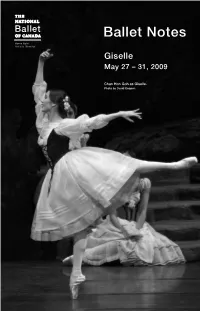

Ballet Notes Giselle

Ballet Notes Giselle May 27 – 31, 2009 Chan Hon Goh as Giselle. Photo by David Cooper. 2008/09 Orchestra Violins Clarinets • Fujiko Imajishi, • Max Christie, Principal Souvenir Book Concertmaster Emily Marlow, Lynn Kuo, Acting Principal Acting Concertmaster Gary Kidd, Bass Clarinet On Sale Now in the Lobby Dominique Laplante, Bassoons Principal Second Violin Stephen Mosher, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., Founder James Aylesworth, Jerry Robinson Featuring beautiful new images Acting Assistant Elizabeth Gowen, George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Concertmaster by Canadian photographer Contra Bassoon Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Jennie Baccante Sian Richards Artistic Director Executive Director Sheldon Grabke Horns Xiao Grabke Gary Pattison, Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Nancy Kershaw Vincent Barbee Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-Leheniuk Derek Conrod Principal Conductor • Csaba Koczó • Scott Wevers Yakov Lerner Trumpets Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Jayne Maddison Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Richard Sandals, Principal Ron Mah YOU dance / Ballet Master Mark Dharmaratnam Aya Miyagawa Raymond Tizzard Aleksandar Antonijevic, Guillaume Côté, Wendy Rogers Chan Hon Goh, Greta Hodgkinson, Filip Tomov Trombones Nehemiah Kish, Zdenek Konvalina, Joanna Zabrowarna David Archer, Principal Heather Ogden, Sonia Rodriguez, Paul Zevenhuizen Robert Ferguson David Pell, Piotr Stanczyk, Xiao Nan Yu Violas Bass Trombone Angela Rudden, Principal Victoria Bertram, Kevin D. Bowles, Theresa Rudolph Koczó, Tuba